Five Steps to Success: A Private Equity Fundraising Checklist

Raising money as a new private equity fund manager can be a daunting task. Breaking down the tasks into a checklist is an effective way of building a compelling and consistent investment strategy.

Raising money as a new private equity fund manager can be a daunting task. Breaking down the tasks into a checklist is an effective way of building a compelling and consistent investment strategy.

An HEC Paris graduate, Frank has advised clients on a range of transactions totaling more than €50 million.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Raising money as a new private equity (PE) fund manager can be a daunting task. I’ve distilled the necessary steps into the following checklist, which should help you put together a compelling investment case for prospective investors.

PE Fundraising Checklist

Private equity investors, also known as limited partners (LPs), usually see hundreds of funds but only invest in a handful of them. To make the cut, it is important to consider all five of these points together to give a convincing case to the inevitable question of “why should we invest in you?”

✅ Articulate your investment strategy and source of competitive advantage.

✅ Budget the size of fund and fees necessary to execute the strategy.

✅ Finalize a legal structure that provides potential flexibility down the road.

✅ Compile investor lists and separate into buckets based on long-term capital allocation goals.

✅ Prepare for the marketing phase with clear return targets and benchmark metrics.

1. What Is Your Investment Strategy and Competitive Advantage?

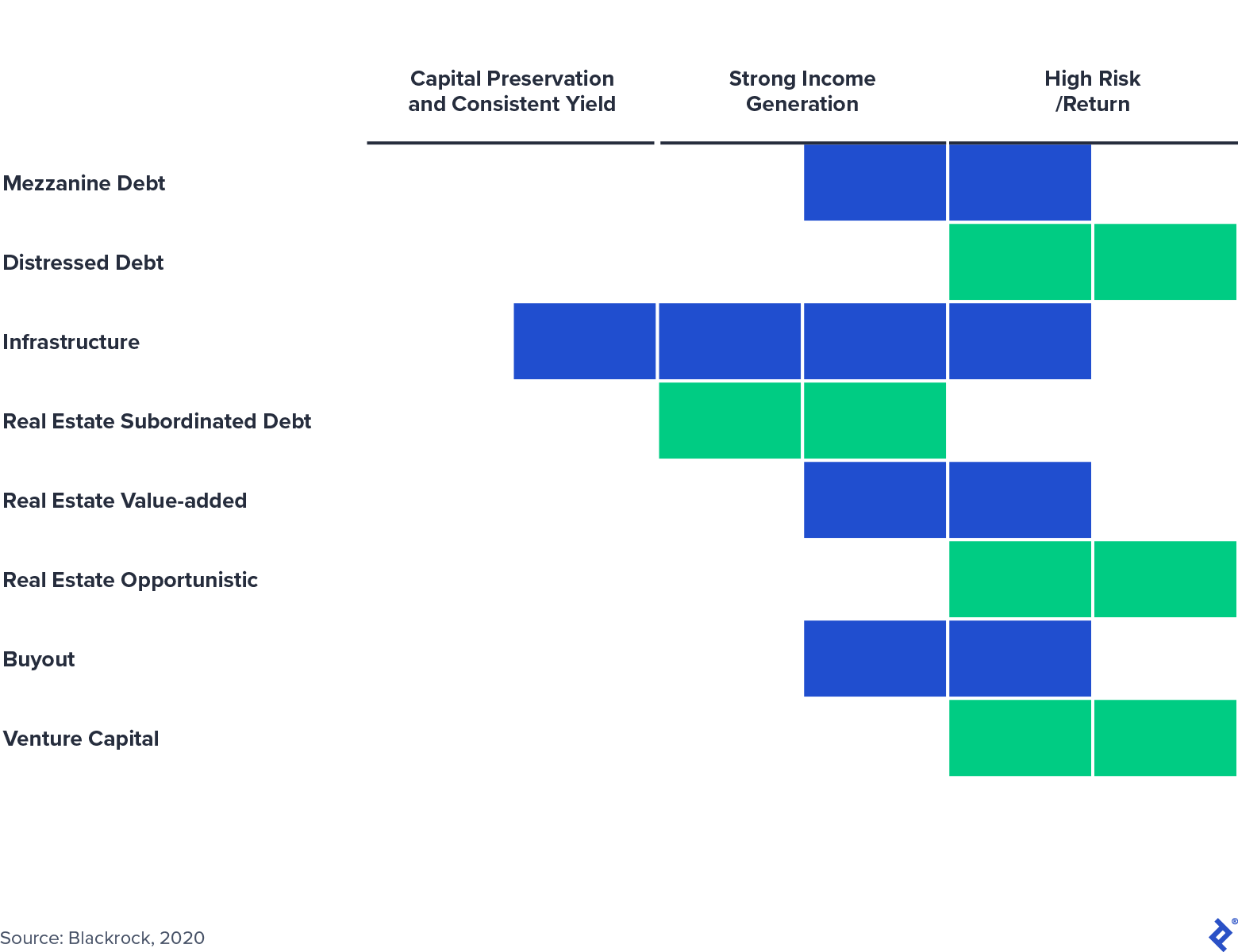

You should articulate your strategy in simple terms and convey what your product will represent within a wider LP allocation. LPs are relying not only on an “asset-based” but also on an “outcome-based” view to determine their allocation. To get them interested, you need to explain which drivers of wealth growth an LP can access by committing funds to you. Each PE strategy has a tradeoff between these wealth drivers:

Exposure of PE Strategies to Desired LP Outcomes

Do You Have a Proven Approach to Achieving Superior Returns? Can Your Strategy Be Easily Replicated?

For first-time fund managers, focus on your unique value proposition and offer a differentiated approach. Be prepared to discuss your competitive landscape and how you plan to source and win deals. You need a solid differentiator during bidding processes—paying the highest price is definitely not the right answer. Make sure to clearly articulate these differentiators so as not to be perceived as a so-called JAMMBOG (just another middle-market buyout group).

If you are just getting started, your biggest asset is focus. Focus helps harness institutional knowledge and differentiated insights that win auctions and create value. As you grow, identify the characteristics of your successful deals and develop pattern recognition for ideal targets. This can help you scale to adjacent sectors and/or geographies as you search for ways to deploy more capital down the road.

What Sources of Value-add Do You Contribute to Portfolio Companies?

Beyond using leverage, PE firms create value by improving the enterprise value of portfolio companies. A larger enterprise value at exit can happen due to revenue growth, margin expansion, or multiple expansion. In recent years, multiple expansion has delivered most of the EV growth across the asset class. Going forward, as multiple expansion slows, general partners (GPs) need to develop new capabilities that rely on the two other levers: revenue growth and margin expansion. You should also consider the role of data science in your strategy across the lifecycle of a fund:

| Investor Relations | Screening and Due Diligence | Portfolio Management |

| a) Digital progression touchpoints with LP b) Customized analytics to answer LP-specific concerns | a) Alternative data and natural language processing to generate leads b) Digitized analytics for due diligence data room | a) Analytics-based segmentation to identify pricing opportunities or to track procurement spending b) Machine learning to identify growth and value drivers |

How Will the Strategy Perform During Downturns?

Make sure to assess cyclical risk in the due diligence process and to develop a view of the overall risk of the portfolio. Possible measures to consider include top-down limits on sector exposure and changing leverage ratios. As an example, Invest Europe, which sets governing principles for PEs and VCs, recommends that LPs consider their exposures to the following risk categories:

- Funding risk: The risk of default on a capital call that could result in the loss of partnership interests

- Liquidity risk: The illiquidity associated with selling the stake in the fund in the secondary market

- Market risk: The fluctuation of the market has an impact on the value of the NAV.

- Capital risk: The capital could be deployed inefficiently by the fund and permanently lost.

Also, look at the levers that you can use within your wider portfolio management strategy to mitigate risk. These can be split into pre- and post-deal, for example, during due diligence for the former and ongoing risk management monitoring for the latter.

Does the Team Being Assembled Provide a Platform for Success?

It’s crucial for your team to have a verifiable track record as a lot of LPs are reluctant to invest in first-time investors. The best way to prove this is attribution letters from former employers. Unfortunately, employers can be reluctant to provide these letters. If that’s your case, there are several alternatives that I will outline later. Ideally, your team should have a verifiable track record for a full cycle to prove that you’re able to handle the full spectrum of the investment process. Even as a new manager, you can break down your track record by actions made at the relevant stages of the investment cycle:

- Deal flow origination: Finding companies, corralling co-investors, and negotiating terms

- Investment performance: The financial returns of deals and/or funds you have managed

- Hiring: Have you unearthed and nurtured talent within your teams?

- Timing: How have your deal entry and exit timings corresponded with macroeconomic cycles?

LPs will invariably see more opportunities than they can possibly fund. Some advice from the BVCA that is particularly valuable is to not pitch yourself as a better alternative to LPs’ existing investments. Be aspirational and informative in your pitch; don’t exaggerate claims or call investors’ judgment into question.

Track Records for Beginners

In real life, many employers are reluctant to give out attribution letters that certify exact involvement in past deals. Luckily, you can use two different ways to prove your involvement to potential LPs:

- Use public information. Provide public evidence of board positions in companies that you invested in or provide public statements mentioning your name as the lead investor.

- Ask for references from other involved parties. Another possibility is to ask the executive team of companies you invested in or funds that co-invested for references.

If none of these options are possible, you could consider creating a new track record prior to raising your fund. Several new managers achieve this through individual deals. Usually, new investors complete between three and five individual deals through special purpose vehicles (SPVs).

The process is as follows: Find an attractive investment consistent with the fund’s planned strategy, convince investors to participate in the deal, create an SPV, and close the deal. It’s important that the rationale behind those investments is consistent with the fund strategy in order to serve as a track record. You should also create a full investor memorandum for every deal to later provide the prospective LPs of your fund with these sample documents. If you are thinking of mentioning personal investments to prove your track record, they are generally irrelevant, especially if their rationale is not consistent with the fund’s strategy.

2. Fund Size and Fees

The size of your fund needs to accommodate your strategy. You need to consider the market map for potential portfolio companies, the size of investment that will be required, and the number of investing partners. It always looks better to set a conservative fund size, be oversubscribed, and raise the target than coming short of your round adjective and taking longer to close. However, LPs will insist on a hard cap that is close to the target, to make sure that you close up fundraising fast and get to investing. LPs also want to control for the alpha decay that comes with larger AUMs due to inefficient deployment of funds on “next best” ideas.

How Competitive Are Your Fees and Terms?

As a first-time fund manager, the most effective strategy is to offer LP friendly terms, meaning the management fee should be at a reasonable level (generally around 2%) and should be reduced after the investment period. The fund should use a European carry mechanism that calculates carried interest on a whole fund basis, and a significant portion of your personal wealth should be committed to the fund. After creating a more developed track record, your fund can slowly adopt more GP-friendly terms, but being LP-friendly at the beginning increases your success rate during the first fundraising.

What Is Your “Sweet Spot”?

As fund size increases, generated alpha can increase at first due to increased buying power and resources necessary to compete for bids. Beyond a certain point, AUM growth translates to inefficient capital deployment and a deteriorating track record. The resulting revenue will be impacted through two different channels:

- The management fee channel. Revenue grows with AUM because of a fixed management fee charged on committed capital during the investment period and adjusted to cost during the harvesting period.

- The performance fee channel. Performance revenue is a factor of capital deployed and realized alpha per unit of deployed capital. Realized alpha per unit of deployed capital generally boils down to the “next best” ideas mentioned earlier, but total performance revenue could still be growing. This illustrates a misalignment of incentives between GPs and LPs and explains the prevalence of hard caps.

Ultimately, taking a long-term view that prioritizes LP relationship preservation will guide your fund size.

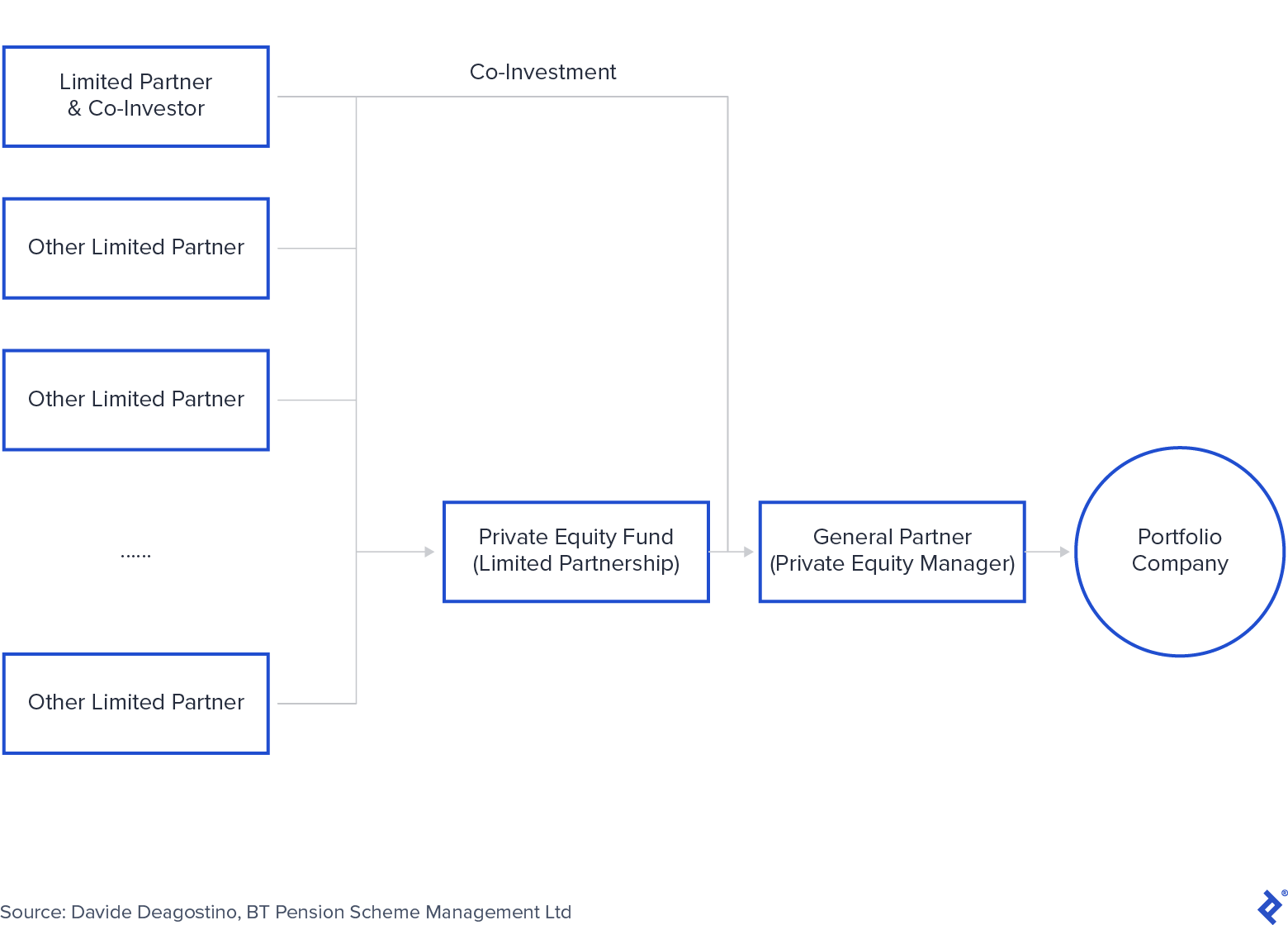

3. Using Co-investments as an LP Magnet

Consideration toward the legal structure of your fund can provide flexibility to “draft” in prospective LPs later on, by initially engaging with them as co-investors. Many LPs seek co-investment opportunities to achieve higher net returns, efficiently control capital deployment, and have better levers on industry/geography exposure. Co-investments are also a great way for LPs to perform ongoing due diligence, especially on new fund managers. On top of this, offering co-investments reduces the blended fee for LPs as no management fee is charged on the co-investment amounts. Co-investments are typically characterized by a shorter duration and predictability on the timing of capital calls.

Co-investments as an LP Magnet

From your perspective, offering co-investments will facilitate access to capital, strengthen relationships with LPs, and manage your fund exposure limits. In a 2015 Preqin survey, 44% of respondents noted that co-investments were a “very important” factor in achieving successful LP solicitations down the line.

4. Appraising the Appropriateness of LPs

Each LP has different concerns, goals, and requirements based on their stakeholders. An LP relationship lasts at a minimum of 10 years. While diversifying your LP base can protect you from unexpected dropouts, it is paramount to focus on LPs with the best fit and be aware of your tradeoffs.

LPs can be split into three buckets, determined by their investment characteristics:

Patient Capital

Large institutional investors are insensitive to business cycle swings and can almost always fulfill their capital commitments. Endowments and pensions may hold large amounts of capital to deploy, but they take longer on due diligence and are restricted by strict mandates. Institutional investors will also expect you to accommodate their reporting requirements, which can be onerous and bureaucratic and may, at times, force you to publicly disclose returns metrics.

Flexible Capital

A fund of funds has the manpower and expertise to facilitate a fast due diligence process. However, a fund of funds manager cares more about fast financial returns to make up for their double layer of fees. These types of funds charge their end investors fees that include both their internal operating costs and the fees passed on by the managers of their underlying investments.

Family offices are also more fast-moving than institutional investors, and their investment goals are very varied and can rely on qualitative aspects that are hard to ascertain. Banks and insurance companies are warming up to the idea of riskier investments but are heavily directed by the prevailing economic, regulatory, and stock market conditions.

Value-add Capital

Corporate LPs invest for knowledge transfer opportunities and to find acquisition targets, but they can also provide assistance in winning deals and guidance during the portfolio management phase. When considering your target LP base, if you envisage hands-on interventions during the portfolio management phase, a strong corporate investor with potential client leads and synergistic assets can be a unique value-add differentiator.

It has become common in recent years for corporations to start their own internal investment divisions, forsaking the tradition of mandating external managers to invest their capital. While this trend is set to continue, there are still many corporations that prefer the expertise of specialist fund managers.

5. Best Practices During the Actual Raise

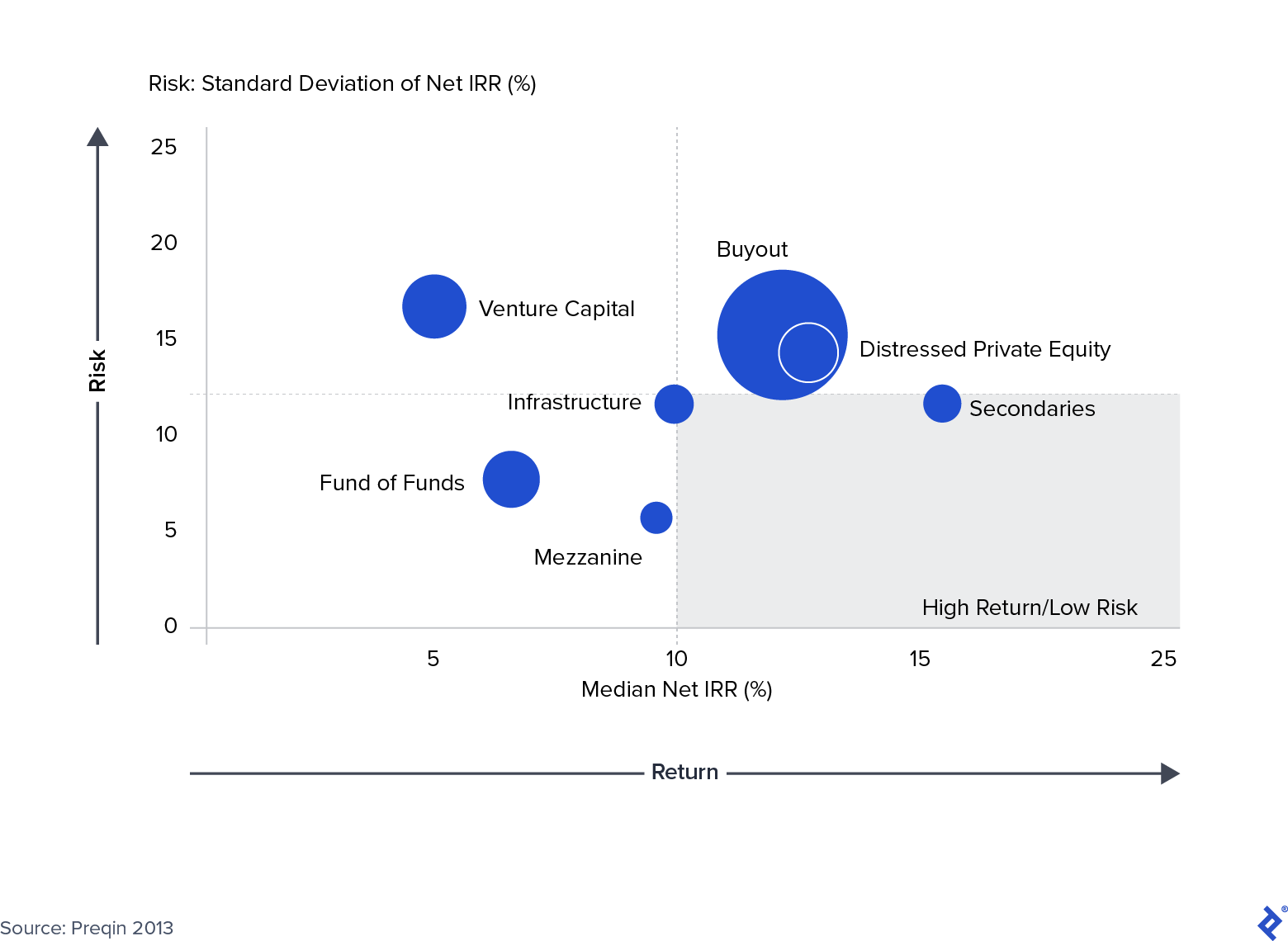

When discussing return metrics with investors, it is important to put them into context in relation to assets of a similar nature. Different types of PE funds have nuanced risk and return tradeoffs, which investors should already be familiar with.

Risk and Return Profile of Private Equity Strategies: 2000-2010 Vintages

Metrics and Benchmarks

To communicate effectively your targets for the fund, compile a list of funds from a range of vintages to show their performance relative to your projections. This provides both transparency and an opportunity to derive new insight from their experiences in the asset class.

In terms of what metrics to communicate, you will be familiar with the names below, but pay attention to the elaboration on why they are important to LPs.

-

Net IRR: Net internal rate of return, which makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows equal to zero for the investor. This measure is time-sensitive: GPs think about gross IRR, but LPs care about net. If investors have obligations on their side for capital return (think back to the fund of funds example), then this metric will be front of mind.

-

TVPI: Total value to paid-in capital is a multiple representing the sum of the cumulative distributions paid out to LPs to date and the residual value of the fund divided by the paid-in capital. Unlike IRR, it does not consider the time value of money and is calculated by summing up two components: the DPI and RVPI:

- DPI: Distributions to paid-in capital is the ratio of cumulative distribution to paid-in capital: “cash-on-cash” returns. This allows the LPs to judge the ability of fund managers to execute on their portfolio strategy and actually deliver positive cash flows to investors. DPI only considers realized and distributed value.

- RVPI: Residual value to paid-in capital is the ratio of the fair value of unrealized net assets in the fund to paid-in capital. This can fluctuate based on the used valuation methods. From an LP perspective, this is an important metric for negotiating a purchase price during secondary deals.

- Loss ratio is the percentage of capital in deals realized below cost, net of any recovered proceeds. This is a measure of volatility and is very important for LPs considering co-investments down the line.

Know that LPs will want to compare these metrics for your fund with aggregate metrics in the industry that have the same strategy and generally place you within a quartile. Some investors have rules about not investing beyond certain quartiles.

Prepare Complete and Impactful Marketing Materials

When you are fundraising, momentum matters. The longer it takes you to close your round, the less favorably you will be perceived by LPs. See your marketing documents, such as the pitch deck, as an ongoing work in progress. The meetings you take form a continual feedback loop where you can refine your message based on the insights you gain from each investor solicited.

You need to prepare a virtual data room with all the necessary information, including a private placement memorandum, a presentation deck, any required due diligence questionnaires, deal attribution analysis, detailed team background, and track record information. Try to make this resource as user-friendly as possible and demonstrate your confidence by being as transparent as possible with the data you show.

Be prepared to provide additional documents very promptly, such as sample reports provided to LPs for prior funds, compliance and ESG policy statements, or a business continuity plan. Try to anticipate and prepare the necessary intelligence to answer LP concerns to ensure an efficient roadshow.

Raise In-house or Use a Placement Agent?

Evaluate your investor relations’ internal capabilities and decide whether you need to enlist the help of a placement agent. Even if you have an IR team ready to take on most of the fundraising effort, consider bringing on a placement agent with a core expertise complementary to yours through a “top-off” mandate. They can help with access to an LP segment or a geography currently outside of your own outreach or with knowledge of investors interested in co-investments.

Placement agents can also give advice on contentious clauses and help structure more LP-friendly economic (fee structure, hurdle rate, waterfall, clawback provisions) and governance (key person and no-fault clauses) terms. On top of this, a well-known placement agent can give you enhanced credibility when negotiating with LPs.

Using a placement agent will result in a financial cost, but consider the potential long-term benefits. If you truly believe in your strategy, a short-term cost will be a necessary hurdle toward reaching your goal.

In Summary: Be Open, Flexible, and Creative

This checklist provides clear steps to follow, but it comes with a caveat: When raising a first-time fund, you must be responsive and ready to adapt when the wind changes. Fundraising cannot be gamified into a fool-proof process, but being prepared is a key step to successfully raising your first PE fund.

Understanding the basics

How does private equity fundraising work?

General partners (GPs) of private equity funds solicit commitments from limited partners (LPs) to invest in them. The process involves pitching the investment vision and how it will result in compelling financial returns. To garner LP support, GPs must also demonstrate a track record and ability to win deals.

What is the difference between a general partner and a limited partner?

Limited partners (LPs) provide capital to investment funds in return for a financial stake in their ongoing performance. They can be individual people or wider institutions. General partners run investment funds and act as fiduciaries to the LPs backing them.

How do you measure private equity fund performance?

Private equity performance is measured on a time-weighted or return multiple basis. The former calculates the discounted cash flow of investments to present value, while the latter measures total investment performance as a multiple of initial capital invested.

Frank Elvinger

London, United Kingdom

Member since June 3, 2020

About the author

An HEC Paris graduate, Frank has advised clients on a range of transactions totaling more than €50 million.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT