iOS User Interfaces: Storyboards vs. NIBs vs. Custom Code

I often hear iOS developers ask some variant of the same key question: “What’s the best way to develop a UI in iOS: through Storyboards, NIBs, or code?”

Answers to this question, explicitly or implicitly, tend to assume that there’s a mutually exclusive choice to be made, one that is often addressed upfront, before development.

I’m of the opinion that there’s no single choice to be made. Rather, each option has its strengths and weaknesses—and there’s no need to use any one of them in isolation.

I often hear iOS developers ask some variant of the same key question: “What’s the best way to develop a UI in iOS: through Storyboards, NIBs, or code?”

Answers to this question, explicitly or implicitly, tend to assume that there’s a mutually exclusive choice to be made, one that is often addressed upfront, before development.

I’m of the opinion that there’s no single choice to be made. Rather, each option has its strengths and weaknesses—and there’s no need to use any one of them in isolation.

Versatile professional with 20+ years experience in a variety of technologies, today focusing mostly on iOS, Swift, Objective C and backend

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

I often hear iOS developers ask some variant of the same key question:

What’s the best way to develop a UI in iOS: through Storyboards, NIBs, or code?

Answers to this question, explicitly or implicitly, tend to assume that there’s a mutually exclusive choice to be made, one that is often addressed upfront, before development.

I’m of the opinion that the answer instead should take the form of one or more counter questions.

What’s the “best” car?

Let me explain with an off-topic example. Say I want to buy a car and I ask you one simple question: “What’s the best choice?”

Can you really answer by suggesting a model, or even a brand? Not likely, unless you suggest a Ferrari. Instead, you’d probably answer with a few other questions, like:

- What’s your budget?

- How many seats do you need?

- Do you care about fuel consumption?

- How do you feel about sports cars?

It’s obvious that there’s no such thing as a good or bad car unless it’s placed in a proper context—there’s just a good or bad car based on specific needs.

Back to iOS UI Design

Just like with our car inquiry, the “What’s the best way to develop an iOS UI” question lacks context. And surprisingly enough, the answer need not be a catch-all case.

Broadly speaking, there are three types of user interface design approaches that you can take, each with its pros and cons, its fans and haters:

- iOS Storyboards: A visual tool for laying out multiple application views and the transitions between them.

- NIBs (or XIBs): Each NIB file corresponds to a single view element and can be laid out in the Interface Builder, making it a visual tool as well. Note that the name “NIB” is derived from the file extension (previously .nib and now .xib, although the old pronunciation has persisted).

- Custom Code: i.e., no GUI tools, but rather, handling all custom positioning, animation, etc. programmatically.

None of these options are universally better than any other (despite what you might hear).

Storyboards, for example, are the latest addition to the iOS UI toolkit. I’ve been told that they’re the future, that they will replace NIBs and custom code UIs. I see Storyboards as a useful tool, but not so much a replacement as a complement for NIBs and custom code. Storyboards are the right choice in some, but not all situations.

Further, why should you statically stick to a single option when you can use them all (in the same project), picking the mechanism that best fits the specific problem at-hand?

This is a question that can be, in my opinion, generalized at a higher level, and whose answer is ranked highly in my list of software development principles: There is no universal language, framework, or technology that is the universal best choice for every software development problem. The same is true for iOS UI design.

In this iOS UI design tutorial, we’re going to explore each of these methods and introduce use cases in which they should and should not be employed, as well as ways in which they can be blended together.

iOS Storyboards

A classic beginner’s mistake is to create one massive project-wide iOS Storyboard. I too made this mistake when I first started working with Storyboards (probably because it’s a tempting route to take). If you need to cover the basics before proceeding, you can consult Apple’s iOS storyboard tutorial.

As its name implies, a Storyboard is a board with a story to tell. It shouldn’t be used to mix unrelated stories into one big volume. A storyboard should contain view controllers that are logically related to each other—which doesn’t mean every view controller.

For example, it makes sense to use Storyboards when handling:

- A set of views for authentication and registration.

- A multi-step order entry flow.

- A wizard-like (i.e., tutorial) flow.

- A master-detail set of views (e.g., profiles lists, profile details).

Meanwhile, large Storyboards should be avoided, including single app-wide Storyboards (unless the app is relatively simple). Before we go any deeper, let’s see why.

The Folly of Large iOS Storyboards

Large Storyboards, other than being difficult to browse and maintain, add a layer of complexity to a team environment: when multiple developers work on the same storyboard file at the same time, source control conflicts are inevitable. And while a storyboard is internally represented as a text file (an XML file, actually), merging is usually non-trivial.

When developers view source code, they ascribes it semantic meaning. So when manually merging, they’re able to read and understand both sides of a conflict and act accordingly. A storyboard, instead, is an XML file managed by Xcode, and the meaning of each line of code is not always easy to understand.

Let’s take a very simple example: say two different developers change the position of a UILabel (using autolayout), and the latter pushes his change, producing a conflict like this (notice the conflicting id attributes):

<layoutGuides>

<viewControllerLayoutGuide type="top" id="ar5-ed-tdC"/>

<viewControllerLayoutGuide type="bottom" id="enX-PS-xZQ"/>

</layoutGuides>

<layoutGuides>

<viewControllerLayoutGuide type="top" id="6cK-2r-Dvq"/>

<viewControllerLayoutGuide type="bottom" id="EbB-ky-ghh"/>

</layoutGuides>

The id itself doesn’t provide any indication whatsoever as to its true significance, so you have nothing to work with. The only meaningful solution is to choose one of the two sides of the conflict and discard the other one. Will there be side effects? Who knows? Not you.

To ease these iOS interface design problems, using multiple user storyboards in the same project is the recommended approach.

When to Use Storyboards

Storyboards are best used with multiple interconnected view controllers, as their major simplification is in transitioning between view controllers. To some degree, they can be thought of as a composition of NIBs with visual and functional flows between view controllers.

Besides easing navigation flow, another distinct advantage is that they eliminate boilerplate code needed to pop, push, present, and dismiss view controllers. Moreover, view controllers are automatically allocated, so there’s no need to manually alloc and init.

Finally, while Storyboards are best used for scenarios involving multiple view controllers, it’s also defensible to use a Storyboard when working with a single table view controller for three reasons:

- The ability to design table cell prototypes in-place helps keep the pieces together.

- Multiple cell templates can be designed inside the parent table view controller.

- It’s possible to create static table views (a long awaited addition that’s unfortunately only available in Storyboards).

One could argue that multiple cell templates can also be designed using NIBs. In truth, this is just a matter of preference: some developers prefer to have everything in one place, while others don’t care.

When Not to Use iOS Storyboards

A few cases:

- The view has a complicated or dynamic layout, best-implemented with code.

- The view is already implemented with NIBs or code.

In those cases, we can either leave the view out of the Storyboard or embed it in a view controller. The former breaks the Storyboard’s visual flow, but doesn’t have any negative functional or development implications. The latter retains this visual flow, but it requires additional development efforts as the view is not integrated into the view controller: it’s just embedded as a component, hence the view controller must interact with the view rather than implementing it.

General Pros and Cons

Now that we have a sense for when Storyboards are useful in iOS UI design, and before we move on to NIBs in this tutorial, let’s go through their general advantages and disadvantages.

Pro: Performance

Intuitively, you can assume that when a Storyboard is loaded, all of its view controllers are instantiated immediately. Fortunately, this is just an abstraction and not true of the actual implementation: instead, only the initial view controller, if any, is created. The other view controllers are instantiated dynamically, either when a segue is performed or manually from code.

Pro: Prototypes

Storyboards simplify the prototyping and mocking up of user interfaces and flow. Actually, a complete working prototype application with views and navigation can be easily implemented using Swift Storyboards and just a few lines of code.

Con: Reusability

When it comes to moving or copying, iOS Storyboards are poorly positioned. A Storyboard must be moved along with all of its dependent view controllers. In other words, a single view controller cannot be individually extracted and reused elsewhere as a single independent entity; it’s dependent on the rest of the Storyboard to function.

Con: Data flow

Data often needs to be passed between view controllers when an app transitions. However, the Storyboard’s visual flow is broken in this case as there’s no trace of this happening in the Interface Builder. Storyboards take care of handling the flow between view controllers, but not the flow of data. So, the destination controller has to be configured with code, overriding the visual experience.

In such cases, we have to rely on a prepareForSegue:sender, with an if/else-if skeleton like this:

- (void) prepareForSegue:(UIStoryboardSegue *)segue sender:(id)sender {

NSString *identifier = [segue identifier];

if ([identifier isEqualToString@"segue_name_1"]) {

MyViewController *vc = (MyViewController *) [segue destinationViewController];

[vc setData:myData];

} else if ([identifier isEqualToString@"segue_name_2"]) {

...

} else if ...

}

I find this approach to be error prone and unnecessarily verbose.

NIBs

NIBs are the old(er) way to perform iOS interface design.

In this case, “old” doesn’t mean “bad”, “outdated”, or “deprecated”. In fact, it’s important to understand that iOS Storyboards aren’t a universal replacement for NIBs; they just simplify the UI implementation in some cases.

With NIBs, any arbitrary view can be designed, which the developer can then attach to a view controller as-needed.

If we apply object-oriented design to our UIs, then it makes sense to break a view controller’s view down into separate modules, each implemented as a view with its own NIB file (or with multiple modules grouped into the same file). The clear advantage to this approach is that each component is easier to develop, easier to test, and easier to debug.

NIBs share the merge conflict problems we saw with Storyboards, but to a lesser extent, as NIB files operate at a smaller scale.

When to Use NIBs for iOS UI Design

A subset of all uses cases would be:

- Modal views

- Simple login and registration views

- Settings

- Popup windows

- Reusable view templates

- Reusable table cell templates

Meanwhile…

When Not to Use NIBs

You should avoid using NIBs for:

- Views with dynamic content, where the layout changes significantly depending on content.

- Views that by nature are not easily designable in the Interface Builder.

- View controllers with complicated transitions that could be simplified with iOS Storyboarding.

General Pros and Cons

More generally, let’s walk through the pros and cons of using NIBs.

Pro: Reusability

NIBs come in handy when the same layout is shared across multiple classes.

As a simple use case, a view template containing a username and a password text field could be implemented with the hypothetical TTLoginView and TTSignupView views, both of which could originate from the same NIB. The TTLoginView would have to hide the password field, and both would have to specify corresponding static labels (such as ‘Enter your username’ vs ‘Enter your password’), but the labels would have the same basic functionality and similar layouts.

Pro & Con: Performance

NIBs are lazily loaded, so they don’t use memory until they have to. While this can be an advantage, there’s latency to the lazy loading process, making it something of a downside as well.

iOS Custom Code (Programmatic UIs)

Any iOS interface design that can be done with Storyboards and NIBs can also be implemented with raw code (there was a time, of course, when developers didn’t have the luxury of such a rich set of tools).

Perhaps more importantly, what cannot be done with NIBs and Storyboards can always be implemented with code—provided, of course, that it’s technically feasible. Another way of looking at it is that NIBs and Storyboards are implemented with code, so their functionality will naturally be a subset. Let’s jump straight into the pros and cons.

Pro: Under the Hood

The greatest advantage of creating an iOS UI programmatically: if you know how to code a user interface, then you know what happens under the hood, whereas the same is not necessarily true of NIBs and Storyboards.

To make a comparison: a calculator is a useful tool. But it’s not a bad thing to know how to perform calculations manually.

This isn’t limited to iOS, but to any visual RAD tool (e.g., Visual Studio and Delphi, just to name a few). Visual HTML RAD environments represent a typical borderline case: they are used to generate (often poorly written) code, claiming that no HTML knowledge is needed, and that everything can be done visually. But no web developer would implement a web page without getting his or her hands dirty: they know that manually handling the raw HTML and CSS will lead to more modular, more efficient code.

So, mastering the coding of iOS user interfaces gives you more control over and greater awareness of how these pieces fit together, which raises your upper-bound as a developer.

Pro: When Code is the Only Option

There are also cases in which custom iOS code is the only option for UI design. Dynamic layouts, where view elements are moved around and the flow or layout adjusts significantly based on content, are typical examples.

Pro: Merge Conflicts

While NIBs and Storyboards suffered significantly from merge conflicts, code doesn’t have the same fault. All code has semantic meaning, so resolving conflicts is no more difficult than usual.

Con: Prototyping

It’s difficult to figure out how a layout will look until you seen it in action. Further, you can’t visually position views and controls, so translating layout specs into a tangible view can take much longer, as compared to NIBs and Storyboards which give you an immediate preview of how things will render.

Con: Refactoring

Refactoring code that was written long ago or by someone else also becomes much more complicated: when elements are being positioned and animated with custom methods and magic numbers, debugging sessions can become arduous.

Pro: Performance

In terms of performance, Storyboards and NIBs are subject to the overhead of loading and parsing; and in the end, they’re indirectly translated into code. Needless to say, this doesn’t happen with code-made UIs.

Pro: Reusability

Any view implemented programmatically can be designed in a reusable fashion. Let’s see a few use cases:

- Two or more views share a common behavior, but they are slightly different. A base class and two subclasses solve the problem elegantly.

- A project has to be forked, with the aim of creating a single code base, but generating two (or more) different applications, each with specific customizations.

The same UI design process would be much more complicated with NIBs and Storyboards. Template files don’t allow inheritance, and the possible solutions are limited to the following:

- Duplicate the NIB and Storyboard files. After that, they have separate lives and no relationship to the original file.

- Override the look and behavior with code, which may work in simple cases, but can lead to significant complication in others. Heavy overrides with code can also render visual design useless and evolve into a constant source of headaches, e.g., when a certain control displays one way in the Interface Builder, but looks completely different when the app is running.

When to Use Code

It’s often a good call to use use custom code for iOS user interface design when you have:

- Dynamic layouts.

- Views with effects, such as rounded corners, shadows, etc.

- Any case in which using NIBs and Storyboards is complicated or infeasible.

When Not to Use Code

In general, code-made UIs can always be used. They’re rarely a bad idea, so I’d put an

Although NIBs and Storyboards bring some advantages to the table, I feel there’s no reasonable downside that I would put in a list to discourage code usage (except, perhaps, laziness).

One Project, Multiple Tools

Storyboards, NIBs, and code are three different tools for building iOS user interface. We’re lucky to have them. Fanatics of programmatic UIs probably won’t take the other two options into account: code lets you do everything that’s technically possible, whereas the alternatives have their limitations. For the rest of the developers out there, the Xcode army knife provides three tools which can be used all at once, in the same project, effectively.

How, you ask? However you like. Here are some possible approaches:

- Group all related screens into separate groups, and implement each group with its own distinct Storyboard.

- Design non-reusable table cells in-place with a Storyboard, inside the table view controller.

- Design reusable table cells in NIBs to encourage reuse and avoid repetition, but load these NIBs through custom code.

- Design custom views, controls, and in-between objects using NIBs.

- Use code for highly dynamic views, and more generally for views that are not easily implementable via Storyboards and NIBs, while housing view transitions in a Storyboard.

To close, let’s look at one last example that ties it all together.

A Simple Use Case

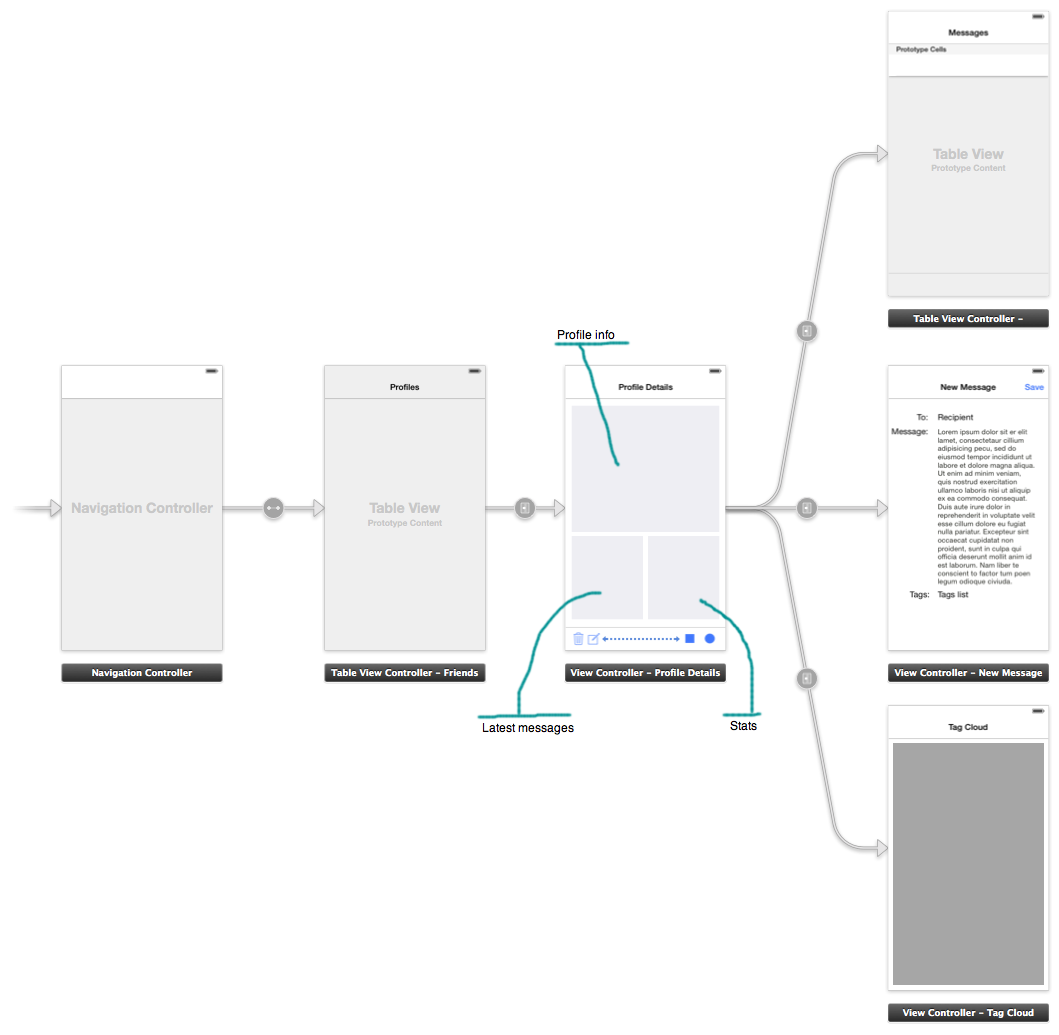

Say we want to develop a basic messaging app with several different views:

- A list of followed friends (with a reusable cell template to keep the UI consistent across future lists).

- A profile detail view, composed into separate sections (including profile information, stats, and a toolbar).

- A list of messages sent to and received from a friend.

- A new message form.

- A tag cloud view that displays the different tags used in user messages, with each tag proportional in size to the number of times it’s been used.

In addition, we want the views to flow as follows:

- Clicking an item in the list of followed friends displays the relevant friend’s profile details.

- The profile details show the profile name, address, statistics, a short list of the most recent messages, and a toolbar.

To implement this iOS app, all three of our UI tools will come in handy, as we can use:

- A Storyboard with four view controllers (the list, details, list of messages, and new message form).

- A separate NIB file for the reusable profile list cell template.

- Three separate NIB files for the profile details view, one for each of the separate sections that compose it (profile details, statistics, last three messages), to allow for better maintainability. These NIBs will be instantiated as views and then added to the view controller.

- Custom code for the tag cloud view. This view is a typical example of one that cannot be designed in the Interface Builder, neither through StoryBoards nor NIBs. Instead, it’s completely implemented through code. In order to maintain the Storyboard’s visual flow, we choose to add an empty view controller to the Storyboard, implement the tag cloud view as a standalone view, and programmatically add the view to the view controller. Clearly, the view could also be implemented inside the view controller rather than as a standalone view, but we keep them separated for better reuse.

A really basic mock-up might look like:

With that, we’ve outlined the basic construction of a reasonably sophisticated iOS app whose core views tie together our three primary approaches to UI design. Remember: there’s no binary decision to be made, as each tool has its strengths and weaknesses.

Wrapping Up

As examined in this turtorial, Storyboards add a noticeable simplification to iOS UI design and visual flow. They also eliminate boilerplate code; but all this comes at a price, paid in flexibility. NIBs, meanwhile, offer more flexibility by focusing on a single view, but with no visual flow. The most flexible solution, of course, is code, which tends to be rather unfriendly and inherently non-visual.

If this article intrigued you, I highly recommend watching the great debate from Ray Wenderlich, 55-minutes well-spent on a discussion of NIBs, Storyboards, and code-made UIS.

In closing, I want to emphasize one thing: Avoid using the improper iOS UI design tool at all costs. If a view is not designable with a Storyboard, or if it can be implemented with NIBs or code in a simpler way, don’t use a Storyboard. Similarly, if a view is not designable using NIBs, don’t use NIBs. These rules, while simple, will go a long way in your education as a developer.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Antonio Bello

Chrzanow, Poland

Member since May 6, 2013

About the author

Versatile professional with 20+ years experience in a variety of technologies, today focusing mostly on iOS, Swift, Objective C and backend

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT