Design Sprints: Fostering Creativity Through Constraints

How can creativity thrive in an environment of rules and set processes? The creative constraints introduced by design sprints can help product managers find the midpoint between structure and chaos.

How can creativity thrive in an environment of rules and set processes? The creative constraints introduced by design sprints can help product managers find the midpoint between structure and chaos.

Daniel is an innovation and product manager with seven years of experience at PwC, and a track record of working creatively and entrepreneurially to bring ideas to life and generate new value streams.

PREVIOUSLY AT

As an innovation and product manager, I work with companies to identify, create, and deliver new sources of value. Sometimes, this value is generated through refining business-as-usual activities; other times, it’s created by offering new products and services to the market. But whatever the driver of value, the key to my work is nurturing the creativity of employees. The people I work with already have the necessary subject matter expertise. My job is to provide them with the structure, space, and support necessary to cultivate this expertise and help them create new value streams.

Enabling creativity at an organizational level is different from doing so one-on-one; you need to reflect on the structures that you have in place to support the generation and delivery of new ideas. You need enough structure to make sure ideas become tangible new outputs but not so much that ideas are strangled and amount to nothing. It’s always a fine balance, no matter the size or complexity of your company.

One of the best ways to drive creativity throughout the business life cycle is through the use of creative constraints—establishing boundaries and limitations in ways that foster, rather than hinder, creativity. My use of design sprints will show you how creative constraints can help you find the midpoint between structure and chaos to bring new ideas to life, unlocking the creative power in every team member while reducing innovation risk.

Understanding the Creativity Spectrum

The business world comprises a broad spectrum of companies that, organizationally, sit somewhere between structure and chaos. On one end of the spectrum are early-stage startups—picture the modern trope of two or three people in a garage or coworking space, huddled around a whiteboard and throwing around new ideas. The environment is often depicted as high energy with little emphasis on process, where the instinct is to chase a promising new idea, perhaps without properly validating it.

On the other end of the spectrum are large, complex, established organizations. These companies are often typified by hierarchy, process, and a focus on operational efficiency. They may have begun life as chaotic startups but have now scaled their offerings, created fixed brand identities, and refined their strategies. From an innovation perspective, they focus primarily on squeezing efficiency gains out of existing products. The instinct here is to spend a lot of time de-risking every new idea before moving on to execution.

From a creativity or innovation standpoint, neither end of this spectrum is a particularly good place for an organization to be. Too much organizational structure stifles the creative process, as employees spend an inordinate amount of time and energy adhering to business processes (e.g., time sheets, stakeholder management, and excessive meetings) and have little remaining time or energy to come up with ideas. Firms that operate in this way are vulnerable to disruption by smaller, nimbler, more chaotic firms. But while less structure might enable more time and space to generate ideas or pivot fluidly, a lack of process by which to birth new ideas is equally stifling. Ideas aren’t properly captured or validated and the product becomes bloated and its purpose confused, leading to a strain on resources and an inability to deliver effectively.

It’s essential to find the midpoint where people have time and space to ideate, and then, if and when the seed of an idea has germinated, the right amount of structure and process to help it grow.

Reaching the Midpoint

A 2018 Journal of Management study sought to reconcile conflicting research on the effect of constraints on innovation; some studies found that input restraints—such as limited time, human capital, or funding—helped foster creativity, whereas others found that these restrictions discouraged innovative thinking. The authors suggest that the extent of the restraint matters: Imposing limitations has an inverted U-shaped effect. Too few make for a complacent team; a moderate number makes the task a challenge, encouraging experimentation and risk; and beyond a certain point, constraints become a problem again, discouraging innovation and demoralizing team members.

To achieve balance, organizations can use creative constraints with intention. Implementing guardrails gives employees a safe environment in which to ideate and take daring, creative risks while not overburdening teams with so many constraints that they become a hindrance.

Think of it like learning to ride a bike: You’re five years old, you’ve seen other kids careening around the neighborhood on their bikes, and you want to do the same. There’s the idea seed. After weeks of pleading, a gleaming metal and plastic frame stands on your front porch. You gasp. How are you actually going to use this thing? Thankfully, your parents have provided training wheels, a helmet, and knee and elbow pads (guardrails to reduce risk), and they forbid you from going past the lamppost or riding without supervision (constraints to limit your actions). These guardrails and constraints provide the structure that allows you to act on your idea. The limitations give you the freedom to begin your journey.

Using Time as a Creative Constraint

Time can be an effective and simple creative constraint. This is why people implement deadlines. While scheduling and time management are important, in my experience, the primary purpose of most deadlines is to require people to be productive and resourceful in accomplishing their tasks.

This same approach can be used in an innovation context, in the use of time-boxed, intensive workshops to solicit new ideas or validate existing ones. If people know that they are only able to think for 25 minutes about something before moving on to something else, they’ll concentrate for those 25 minutes. The widespread use of the Pomodoro Technique, in which work is conducted in short timed increments, is one example of how effective time constraints can be.

One of my favorite ways to use time to drive creativity and productivity among teams is in the design sprint process. Any organization—with the right commitment of time and resources—can use this approach.

Design Sprints

Pioneered at GV, a design sprint is a facilitated, time-boxed, five-day process that provides space and structure for teams to quickly test and prototype new ideas to solve a predefined “problem statement.” Each of the five days is split into themes, and each day is further split into an intensive series of smaller, time-boxed workshops, so people are working synchronously on a number of different areas of the same product.

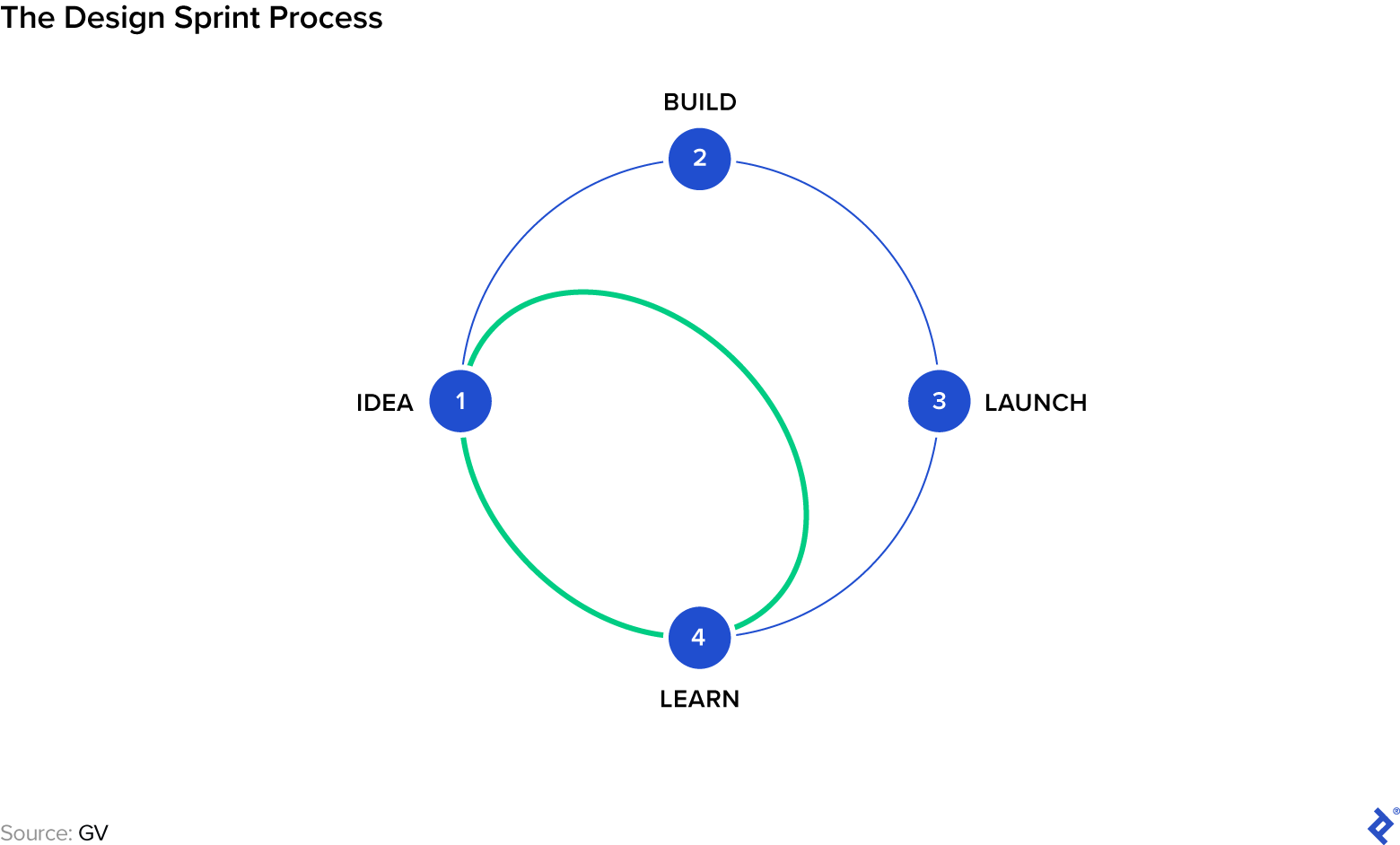

The design sprint builds off of the traditional four-stage development cycle: idea, build, launch, and learn. In traditional product development, teams are only able to gather feedback and iterate on their product in the final stage—after the costly and time-consuming process of building and launching a product. The design sprint process aims to reduce innovation risk by focusing on prototyping and testing an idea quickly with users. GV describes this process as providing a shortcut between “idea” and “learn,” allowing the team to grow and experiment without upfront investment. The lessons learned in a design sprint can inform whether the team goes on to build the product or not.

The key to a design sprint, however, is that the whole process takes place in one week. Each stage of the process is time-boxed to one day, and the time constraints force teams to think quickly and creatively. The daily activities of the design sprint provide structure for more chaotic teams, giving them a defined process with defined outputs. But those daily activities also introduce an element of chaos for more structured teams, forcing them to move quickly and think creatively due to the time constraints.

What Do You Need?

Experienced facilitators typically run these sessions, but with the right guidance and collateral, anyone can learn to be a sprint facilitator. To run your own design sprint, you’ll need:

- A problem statement.

- A team of seven (or fewer) consisting of at least one facilitator (including you) and representatives from a range of other roles, such as product owner, designer, engineer, subject matter expert, or marketing expert.

- Five days of time blocked off for each participant with other work kept to a minimum (meeting schedules cleared, notifications muted).

- A series of workshops that are designed to help a team solve the problem statement quickly.

- A dedicated space with sticky notes and whiteboards for in-person sessions or collaboration software (e.g., Miro or Google Jamboard) for virtual gatherings.

How Does It Work?

While the exact format can vary from sprint to sprint, depending on the requirements of the company and the preference of the sprint facilitator, each of the five days generally focuses on a different theme, and each themed day contains a series of small workshops.

Design sprints tend to focus, understandably, on design. But the format is flexible enough to customize it to the needs of your business and your team. Personally, I like bringing more business acumen into the process than is found in a typical design sprint. My process might look something like this:

-

Day 1. Understanding the Problem Space

- Allow the sprint team to interview pre-identified key stakeholders/experts about the problem space.

- Draw a customer journey map.

- Create customer personas.

- Define long-term goals for the project/product.

-

Day 2. Ideating and “What’s happening in the market?”

- Run a Crazy 8s/solution sketching exercise.

- Conduct competitive analysis.

- Scan and size the market.

- Define customers to test with on Day 5.

-

Day 3. Storyboarding

- Storyboard the solution as a team.

- Construct the technical architecture (if appropriate).

-

Day 4. Prototyping and Business Case

- Begin to prototype the solution.

- Complete the business model canvas.

-

Day 5. User Testing and Playback to Stakeholders

- Test initial ideas with users/customers and capture feedback.

- Share progress with stakeholders/investors (if appropriate).

By the end of the week, the team will have produced a prototyped solution, gotten feedback from customers, and explored the core areas of the solution’s business model canvas. In the normal course of development, this might take months.

I’ve used design sprints to protect teams from corporate structures, giving them sandboxes where they can innovate and take risks without the danger of impacting the rest of the business. The freedom provided by the sprints’ guardrails and the motivation provided by time constraints enable teams to act in nimble ways but with just the right amount of scarcity to incentivize creative and decisive action.

Finding the Right Balance

No matter the size or scale of an organization, the work environment that’s provided for employees is crucial in enabling them to innovate effectively. Ask yourself: Are employees incentivized to come up with new ideas? If an employee came up with a groundbreaking idea, would they feel empowered to come forward with it? If an employee came up with a groundbreaking idea, would the company know what to do with it?

Much has been written about employees’ desire for autonomy in the current workforce. But at the same time, laissez-faire management and a lack of role clarity have a negative impact on employee well-being, and chaotic startups that can’t make the transition to more orderly, hierarchical structures are prone to failure. Business environments must broaden their creative processes to include both the space and freedom to generate ideas and the structures that bring these ideas to life.

You can download a PDF of the following infographic and use it as a guide to start planning design sprints for your teams.

{:target="_blank"}. The phrase "Crazy 8s" links to [https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/methodology/phase3-sketch/crazy-8s](https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/methodology/phase3-sketch/crazy-8s){:target="_blank"}. The phrase "business model canvas links to [https://miro.com/templates/business-model-canvas](https://miro.com/templates/business-model-canvas){:target="_blank"}.](https://assets.toptal.io/images?url=https%3A%2F%2Fbs-uploads.toptal.io%2Fblackfish-uploads%2Fpublic-files%2FInfographicPreview_DanielHatton_DesignSprints-219f1712bb3bcc0f65d0318a67bfacbb.png)

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- Creativity Exercises to Boost Your Designs

- What Is Strategic Design Thinking and How Can It Empower Designers?

- Great Questions Lead to Great Design: A Guide to the Design-thinking Process

- 30 Days of Design: A Branding Case Study

- The Best UX Designer Portfolios: Inspiring Case Studies and Examples

- Defining Who, What, and Why: How to Write a User Story

Understanding the basics

What are examples of creative constraints?

Creative constraints are any resources that are purposefully limited to promote creative effort. Time can be used as a creative constraint, as can budget or human capital.

How do constraints enhance creativity?

Creative constraints compel people to work within set parameters and, if used correctly, inspire them to complete the work in ways that open-ended assignments would not. For instance, a deadline forces someone to work within a set time frame.

What is the purpose of a design sprint?

A design sprint is used to accelerate a team through the development process in a one-week span, providing a shortcut between the “idea” and “learn” stages of the design process.

What are the advantages of a design sprint?

In addition to providing a prototype and user feedback in a very short span of time, the design sprint process provides a low-risk environment for innovation where teams can experiment without the expense of building and launching a product.

Daniel Hatton

London, United Kingdom

Member since November 22, 2021

About the author

Daniel is an innovation and product manager with seven years of experience at PwC, and a track record of working creatively and entrepreneurially to bring ideas to life and generate new value streams.

PREVIOUSLY AT