Every Product Has a Thesis

Every successful product has a central thesis—a reason for existence. Let’s analyze the foundations of the iPhone, Alexa, and other widespread products to highlight their core theses.

Every successful product has a central thesis—a reason for existence. Let’s analyze the foundations of the iPhone, Alexa, and other widespread products to highlight their core theses.

Alex is a product manager at the intersection of design and commerce, helping clients convert leads into sales.

PREVIOUSLY AT

Every successful product has a reason for existence and a justification for why people love it—a so-called central thesis. If a thesis is not aligned with users’ needs, the product tends to do a lot of different things but ends up doing nothing well. When Amazon released the Fire Phone in 2014, its failure was partly due to the fact that “consumers considered its smartphone effort utterly misguided.” Another example is Google+, which was launched as a Facebook clone with “big aspirations but no well-defined purpose for users.”

Product thesis is crucial for targeting the proper market successfully and showcasing a product’s uniqueness to users. In this article, I will analyze the foundations of four well-known products to highlight their core theses and the lessons learned from their introduction to the market.

What Is a Product Thesis?

A core thesis is similar to a product vision, it is a solution to a problem. Each new feature intends to support that solution and thus strengthen the thesis. Every item, be it hardware, software, or a physical item, has a thesis. The mug sitting next to you, the pencil, or the wallet in your pocket—they all represent a solution that solves a certain problem.

Some products seek to solve several problems. For example, a social media platform like Facebook offers different solutions, including the news feed (showing relevant information for users), messenger (easy chat), or marketplace (selling and buying things within communities). They all are solutions to certain user problems.

Spotting a Thesis

Spotting the core product statement is crucial to determining the initial market entry. By researching a market, you can grasp the customer’s problems and their solutions. When you find a problem without a solution or you can prove that your idea is advanced, it is the right time to crystalize your initial product’s thesis.

When I worked at the travel platform Expedia, I had to build a travel app for college students. First, I immersed myself in the research: I downloaded every app that my customers were using and tested it to determine its thesis. By doing this, I was able to predict the product’s roadmap, as its trajectory derives from the thesis. For example, an app designed to make rapid multi-platform flight comparisons would likely expand into additional comparison verticals, such as hotel or car rental comparisons; an app designed to negotiate hotel prices would likely scale to more cities with a focus on offering the best hotel price. As a new player in the market, you can predict the competitors’ strategy and outperform them.

Spotting a thesis requires immersing yourself in a product to grasp its features and discover the prevailing patterns. If you cannot detect them, most likely there is no central thesis. Typically, this implies a risk of failure, however, there are some well-known products that proved to be an exception to this rule.

The First Story: iPhone

When Apple introduced its first smartphone in 2007, it was the first entirely touch-based smartphone, later recognized as a prototype for current cell phones. It entered the market with the thesis that phones are the perfect use case for touchscreens. This revolutionary idea resulted in major hardware and software changes. Mini scroll wheels or physical keyboards were replaced by finger navigation. The iPhone was designed with more screen space, which was a game-changer for taking images and using apps. Although there were touchscreen phones prior to the iPhone, it was the first phone fully designed around it.

However, the device was not perfect. Switching from Blackberry’s physical keyboard to a touchscreen keyboard meant users lost the ability to type without looking at the keyboard and had to learn to type on smooth glass. In addition to this input shift, the original iPhone did not have the bells and whistles we take for granted in today’s smartphones. There were no games or the App Store, so the default apps were the only ones the user could have. However, they were designed to use a doubled screen to its capacity—the keyboard was allotted by showing either the letters and symbols or the number pad. By being dead set on perfecting touch and aligning the entire user experience around it, Apple’s product team convinced the world that touchscreens and the larger screens they afforded were the future of smartphones.

The Second Story: Alexa

Big enterprises with a long runway can take the risk of launching products without a clear thesis and crystalize or adjust the thesis afterward, based on data showing what feature set users value the most. It is an expensive and risky method but an effective way to understand users’ needs and preferences. If users find the initial product valuable, a company can reorient its feature set around the key incentive and turn it into a successful product.

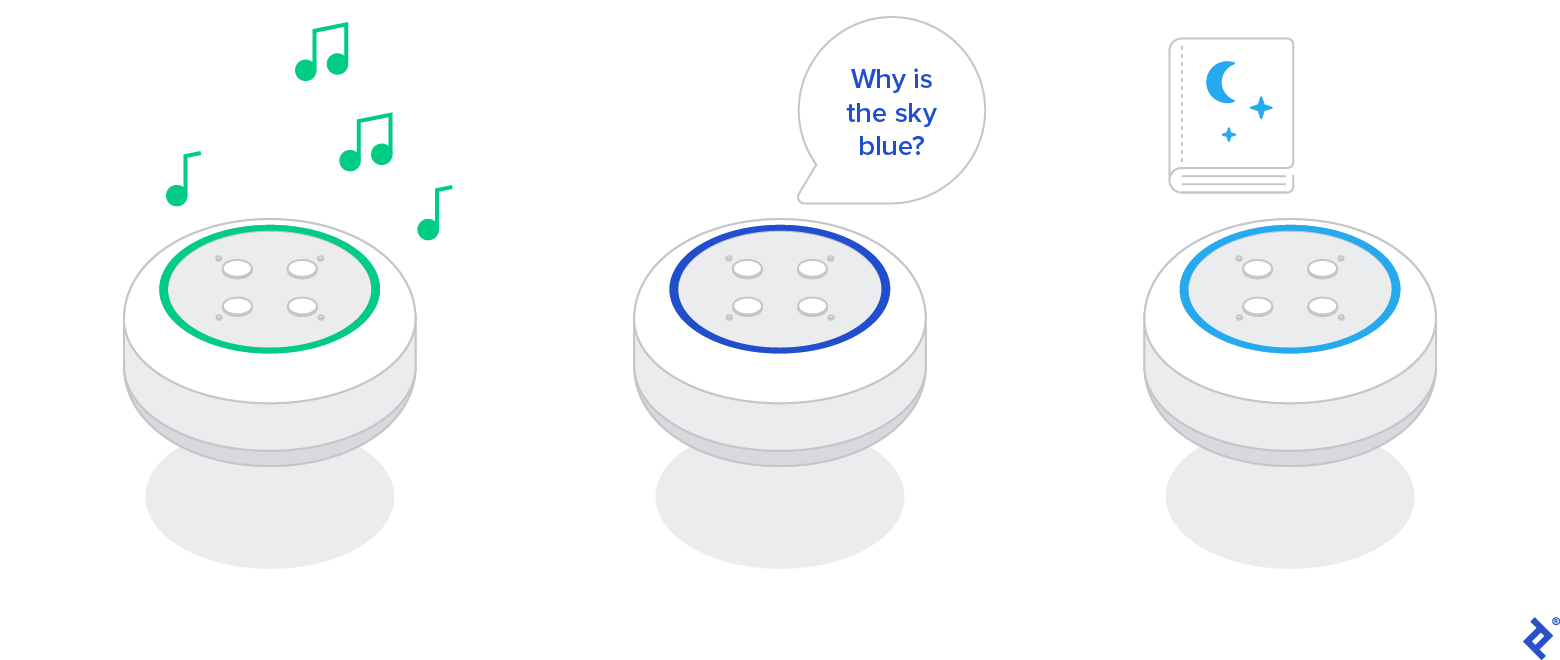

A good example is the Alexa home assistant that Amazon launched in 2014, three years after Apple released Siri. Initially, Alexa’s thesis was that the best place for a voice assistant was the kitchen counter. At launch, it had eight microphones (which was a lot) to catch every single sound in the house and was chock-full of features that were considered to be helpful to a household.

As people slowly began to adopt and love Alexa in their homes, a few clear patterns came into view. Rather than using Alexa to buy things, people mostly used this device to play music, set timers, ask fact-based questions, and get weather forecasts. Unlike the Siri voice assistant on the phone, designed to do personal tasks like calling friends or setting calendar appointments, Alexa was created for family members to share. The focus on assisting everyone rather than a single person seems to have inspired some of Alexa’s unique features such as bedtime stories, jokes, and news briefings. Over time, the Alexa product team also invested in what their users seem to care about: great sound quality at an affordable price to help with simple tasks. This shifted the thesis from the kitchen-based assistant for purchasing products to an affordable speaker that helps the family, making this product one of the market leaders.

The Third Story: Apple Watch

When the first iteration of the Apple Watch was released in 2015, it had no discernible thesis. Smartwatches had existed for years before Apple introduced its product. The Pebble watch was showing notifications and Garmin was an activity tracker for running. The Apple Watch seemed to cover everything—it had apps, notifications, and heart rate, but did none of those things particularly well. In addition, it was tethered to the iPhone, so users needed to carry both their watch and phone with them, which was not ideal for running. After a couple more iterations, with the Apple Watch Series 3, the watch’s thesis became squarely about health. With each subsequent iteration, Apple added more features focused on health, from electrocardiography to heart irregularity detection. The company untethered the watch from the phone, increased health tracking accuracy, and brought the product to the forefront with new interface complexity.

Fourth story: Minut Smart Home Sensor

Although it is a natural temptation for product managers to build many features, the thesis concept suggests they should not be overworked—more does not mean better. A good but not so widely known example is Minut Smart Home Sensor. It analyzes sound at home to identify safety concerns such as break-ins, fire, carbon monoxide leaks, or even mold growth, and then sends notifications to the owner. If you rent your apartment with a “no party” rule, and someone throws a big party, the Sensor will send you a message about a possible party going on based on its sound analysis. It also measures temperature and humidity, and on top of that, tracks motion in the house, so you can know when your guests check out.

At a glance, the Sensor has many different features. However, its thesis is constructed around home security: analyzing sounds to detect threats to home safety. The additional sensors that identify temperature, humidity, and air pressure broaden the home safety concept to protecting the home from mold, sudden temperature peaks and drops, or air pollution.

People do not seek to interact with home security every day; they prefer to be alerted only if issues arise. Minut’s product team took this insight seriously, laying the product’s foundations on this user preference and not overworking with smart features. For example, inserting a voice assistant, alarm clock, or screen to display temperature and weather could confuse the thesis, because these are features we use every day. Also, the functions of an assistant, alarm clock, and security system would compete with each other and risk fulfilling many tasks ordinarily rather than one exceptionally well.

Make the Thesis Flexible

The thesis is not a rigid concept, it is a flexible product vision that needs constant adjustments. Some companies adjust their thesis with every major iteration. The first iPhone version was focused on the screen, later it shifted to better apps, and finally to the camera. When customers and the market validate a product’s thesis by making it a success, competing companies typically adopt it as well and start copying the product. The thesis was compelling, customers bought it, and now that feature set is table stakes. Each iteration of a successful product will now need a different reason to exist—a new thesis—in order to differentiate itself from the imitators.

Sometimes, products with a strong thesis fail. To avoid this, conduct comprehensive user research and make sure your team is ready to pivot into building a new product. While working for a travel platform, I found that almost a third of college-aged people ranked group bookings as one of their biggest travel frustrations. We also discovered that a high number of solo travelers had trouble finding the cheapest itinerary. Both were significant problems—one applied to a huge number of trips, the other to far fewer trips but had a much larger payout per trip. My team was divided. Half of them sought to solve group trips, while the other half wanted to recommend tailored trip itineraries. I encouraged my team to answer the question: “If every solution failed, how would we pivot?” The answer, which led us to focus on recommending itineraries, was that pivoting from a trip comparison platform to nearly any other travel product would be smoother than pivoting out of a group travel coordination product. Collaboration requires many features and tools that are not travel-related, such as polling the group, listing itinerary updates, and inviting group members to share itineraries.

The Big Picture

Composing a product thesis is an essential responsibility of every product manager. The thesis allows teams to get acquainted with a global picture of the market and position their product accordingly. Presenting the thesis to users is another challenge. While some products launch with a solid thesis that immediately matches customers’ needs, a host of companies do not crystallize the thesis until after launch. Both approaches can lead to success as long as you are prepared to tweak, or in case of failure, shift the product’s thesis to meet customers’ needs.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- Product Managers vs. Project Managers Part II: Situational Analysis

- Design Problem Statements: What They Are and How to Frame Them

- How to Lead Remote Product Teams: Key Traits for Success

- The Importance of Human-centered Design in Product Design

- Product Managers vs. Project Managers: Understanding Core Similarities and Differences

Understanding the basics

What is a product statement?

A product statement, also known as a vision statement or thesis, is the imaginary future that you wish to achieve with a product. It is an ambitious and inspiring statement that immerses you into using the product and suggests a great experience.

What is an example of a vision statement?

Good examples of a vision statement are the following: 1) A world where you can belong anywhere (Airbnb, home rental platform); 2) Make second-hand as a first choice worldwide (Vinted, second-hand clothing marketplace); 3) From traveling alone in the urban jungle to having a friend to guide you through (Trafi, mobility platform for cities).

Why is a product vision important?

A product vision aligns a team with the product’s goal and gives the north star to which team members can constantly refer. The vision also inspires the employees and suggests the best possible user experience.

What are the desirable qualities of a product vision?

The desirable qualities of a product vision should cover users’ and company’s perspectives. From the company’s perspective, it should set standards with its philosophy, guide, and inspire employees. From the users’ perspective, it should help people to sympathize with the brand and encourage them to use the product.

How do you write a product statement?

If you want to write a product statement, first define what is unique about your product that differentiates it from others. Second, imagine the future that you want to achieve with your product: What is the best-case scenario? Third, combine it with a product’s features in order to make a short, appealing, and inspirational statement.

Alex Cox

Washington, DC, United States

Member since October 31, 2019

About the author

Alex is a product manager at the intersection of design and commerce, helping clients convert leads into sales.

PREVIOUSLY AT