Optimize Your Environment for Development and Production: A Pydantic Tutorial, Part 2

Learn how to develop a Django application coupled with pydantic where the development environment matches production.

Learn how to develop a Django application coupled with pydantic where the development environment matches production.

Arjaan is a senior engineer and data scientist who creates mission-critical cloud solutions focused on Rasa for international banks and insurance companies. He architects and teaches large-scale Kubernetes solutions.

PREVIOUSLY AT

This is the second installment in a series on leveraging pydantic for Django-based projects. In the series’ first installment, we focused on pydantic’s use of Python type hints to streamline Django settings management.

Developers can be their own worst enemies. I have seen countless examples of engineers developing on a system that doesn’t match their production environment. This dissonance leads to extra work and not catching system errors until later in the development process. Aligning these setups will ultimately ease continuous deployments. With this in mind, we will create a sample application on our Django development environment, simplified through Docker, pydantic, and conda.

A typical development environment uses:

- A local repository.

- A Docker-based PostgreSQL database.

- A conda environment (to manage Python dependencies).

Pydantic and Django are suitable for projects both simple and complex. The following steps showcase a simple solution that highlights how to mirror our environments.

Git Repository Configuration

Before we begin writing code or installing development systems, let’s create a local Git repository:

mkdir hello-visitor

cd hello-visitor

git init

We’ll start with a basic Python .gitignore file in the repository root. Throughout this tutorial, we’ll add to this file before adding files we don’t want Git to track.

Django PostgreSQL Configuration Using Docker

Django requires a relational database and, by default, uses SQLite. We typically avoid SQLite for mission-critical data storage as it does not handle concurrent user access well. Most developers opt for a more typical production database, like PostgreSQL. Regardless, we should use the same database for development and production. This architectural mandate is part of The Twelve-factor App.

Luckily, operating a local PostgreSQL instance with Docker and Docker Compose is a breeze.

To avoid polluting our root directory, we’ll put the Docker-related files in separate subdirectories. We’ll start by creating a Docker Compose file to deploy PostgreSQL:

# docker-services/docker-compose.yml

version: "3.9"

services:

db:

image: "postgres:13.4"

env_file: .env

volumes:

- hello-visitor-postgres:/var/lib/postgresql/data

ports:

- ${POSTGRES_PORT}:5432

volumes:

hello-visitor-postgres:

Next, we’ll create a docker-compose environment file to configure our PostgreSQL container:

# docker-services/.env

POSTGRES_USER=postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD=MyDBPassword123

# The 'maintenance' database

POSTGRES_DB=postgres

# The port exposed to localhost

POSTGRES_PORT=5432

The database server is now defined and configured. Let’s start our container in the background:

sudo docker compose --project-directory docker-services/ up -d

It is important to note the use of sudo in the previous command. It will be required unless specific steps are followed in our development environment.

Database Creation

Let’s connect to and configure PostgreSQL using a standard tool suite, pgAdmin4. We’ll use the same login credentials as previously configured in the environment variables.

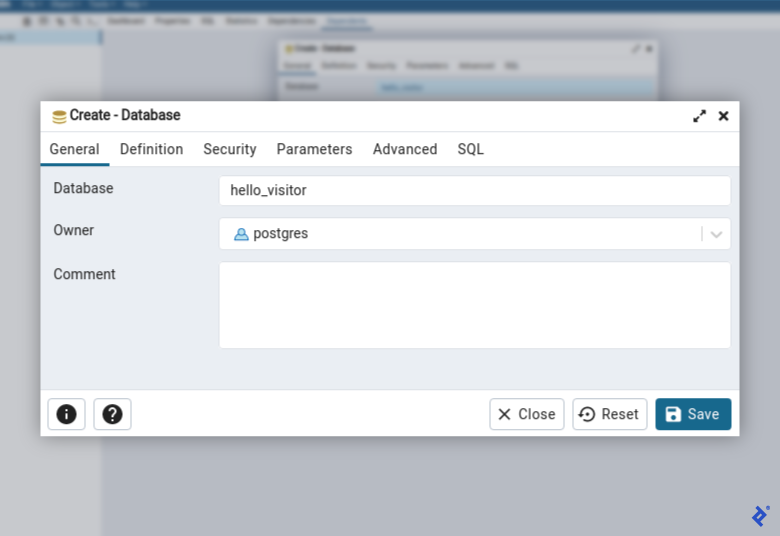

Now let’s create a new database named hello_visitor:

With our database in place, we are ready to install our programming environment.

Python Environment Management via Miniconda

We now need to set up an isolated Python environment and required dependencies. For simplicity of setup and maintenance, we chose Miniconda.

Let’s create and activate our conda environment:

conda create --name hello-visitor python=3.9

conda activate hello-visitor

Now, we’ll create a file, hello-visitor/requirements.txt, enumerating our Python dependencies:

django

# PostgreSQL database adapter:

psycopg2

# Pushes .env key-value pairs into environment variables:

python-dotenv

pydantic

# Utility library to read database connection information:

dj-database-url

# Static file caching:

whitenoise

# Python WSGI HTTP Server:

gunicorn

Next, we’ll ask Python to install these dependencies:

cd hello-visitor

pip install -r requirements.txt

Our dependencies should now be installed in preparation for the application development work.

Django Scaffolding

We’ll scaffold our project and app by first running django-admin, then running a file it generates, manage.py:

# From the `hello-visitor` directory

mkdir src

cd src

# Generate starter code for our Django project.

django-admin startproject hello_visitor .

# Generate starter code for our Django app.

python manage.py startapp homepage

Next, we need to configure Django to load our project. The settings.py file requires an adjustment to the INSTALLED_APPS array to register our newly created homepage app:

# src/hello_visitor/settings.py

# ...

INSTALLED_APPS = [

"homepage.apps.HomepageConfig",

"django.contrib.admin",

# ...

]

# ...

Application Setting Configuration

Using the pydantic and Django settings approach shown in the first installment, we need to create an environment variables file for our development system. We’ll move our current settings into this file as follows:

- Create the file

src/.envto hold our development environment settings. - Copy the settings from

src/hello_visitor/settings.pyand add them tosrc/.env. - Remove those copied lines from the

settings.pyfile. - Ensure the database connection string uses the same credentials that we previously configured.

Our environment file, src/.env, should look like this:

DATABASE_URL=postgres://postgres:MyDBPassword123@localhost:5432/hello_visitor

DATABASE_SSL=False

SECRET_KEY="django-insecure-sackl&7(1hc3+%#*4e=)^q3qiw!hnnui*-^($o8t@2^^qqs=%i"

DEBUG=True

DEBUG_TEMPLATES=True

USE_SSL=False

ALLOWED_HOSTS='[

"localhost",

"127.0.0.1",

"0.0.0.0"

]'

We’ll configure Django to read settings from our environment variables using pydantic, with this code snippet:

# src/hello_visitor/settings.py

import os

from pathlib import Path

from pydantic import (

BaseSettings,

PostgresDsn,

EmailStr,

HttpUrl,

)

import dj_database_url

# Build paths inside the project like this: BASE_DIR / 'subdir'.

BASE_DIR = Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent

class SettingsFromEnvironment(BaseSettings):

"""Defines environment variables with their types and optional defaults"""

# PostgreSQL

DATABASE_URL: PostgresDsn

DATABASE_SSL: bool = True

# Django

SECRET_KEY: str

DEBUG: bool = False

DEBUG_TEMPLATES: bool = False

USE_SSL: bool = False

ALLOWED_HOSTS: list

class Config:

"""Defines configuration for pydantic environment loading"""

env_file = str(BASE_DIR / ".env")

case_sensitive = True

config = SettingsFromEnvironment()

os.environ["DATABASE_URL"] = config.DATABASE_URL

DATABASES = {

"default": dj_database_url.config(conn_max_age=600, ssl_require=config.DATABASE_SSL)

}

SECRET_KEY = config.SECRET_KEY

DEBUG = config.DEBUG

DEBUG_TEMPLATES = config.DEBUG_TEMPLATES

USE_SSL = config.USE_SSL

ALLOWED_HOSTS = config.ALLOWED_HOSTS

# ...

If you encounter any issues after completing the previous edits, compare our crafted settings.py file with the version in our source code repository.

Model Creation

Our application tracks and displays the homepage visitor count. We need a model to hold that count and then use Django’s object-relational mapper (ORM) to initialize a single database row via a data migration.

First, we’ll create our VisitCounter model:

# hello-visitor/src/homepage/models.py

"""Defines the models"""

from django.db import models

class VisitCounter(models.Model):

"""ORM for VisitCounter"""

count = models.IntegerField()

@staticmethod

def insert_visit_counter():

"""Populates database with one visit counter. Call from a data migration."""

visit_counter = VisitCounter(count=0)

visit_counter.save()

def __str__(self):

return f"VisitCounter - number of visits: {self.count}"

Next, we’ll trigger a migration to create our database tables:

# in the `src` folder

python manage.py makemigrations

python manage.py migrate

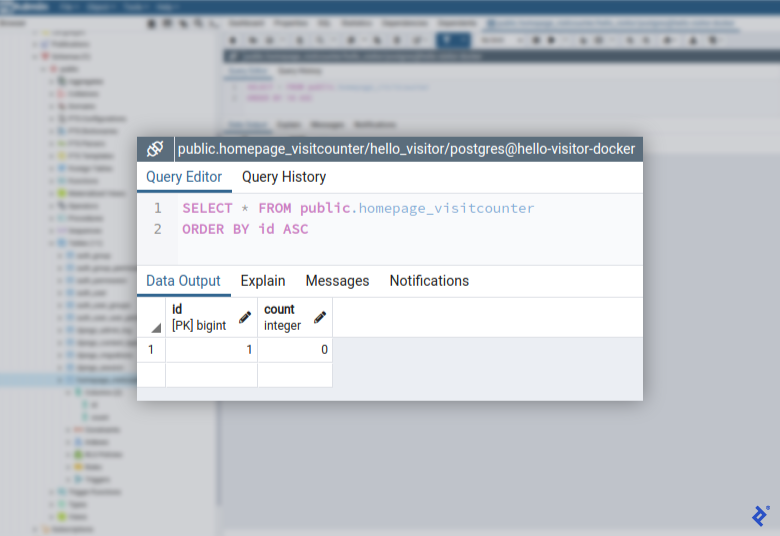

To verify that the homepage_visitcounter table exists, we can view the database in pgAdmin4.

Next, we need to put an initial value in our homepage_visitcounter table. Let’s create a separate migration file to accomplish this using Django scaffolding:

# from the 'src' directory

python manage.py makemigrations --empty homepage

We’ll adjust the created migration file to use the VisitCounter.insert_visit_counter method we defined at the beginning of this section:

# src/homepage/migrations/0002_auto_-------_----.py

# Note: The dashes are dependent on execution time.

from django.db import migrations

from ..models import VisitCounter

def insert_default_items(apps, _schema_editor):

"""Populates database with one visit counter."""

# To learn about apps, see:

# https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/3.2/topics/migrations/#data-migrations

VisitCounter.insert_visit_counter()

class Migration(migrations.Migration):

"""Runs a data migration."""

dependencies = [

("homepage", "0001_initial"),

]

operations = [

migrations.RunPython(insert_default_items),

]

Now we’re ready to execute this modified migration for the homepage app:

# from the 'src' directory

python manage.py migrate homepage

Let’s verify that the migration was executed correctly by looking at our table’s contents:

We see that our homepage_visitcounter table exists and has been populated with an initial visit count of 0. With our database squared away, we’ll focus on creating our UI.

Create and Configure Our Views

We need to implement two main parts of our UI: a view and a template.

We create the homepage view to increment the visitor count, save it to the database, and pass that count to the template for display:

# src/homepage/views.py

from django.shortcuts import get_object_or_404, render

from .models import VisitCounter

def index(request):

"""View for the main page of the app."""

visit_counter = get_object_or_404(VisitCounter, pk=1)

visit_counter.count += 1

visit_counter.save()

context = {"visit_counter": visit_counter}

return render(request, "homepage/index.html", context)

Our Django application needs to listen to requests aimed at homepage. To configure this setting, we’ll add this file:

# src/homepage/urls.py

"""Defines urls"""

from django.urls import path

from . import views

# The namespace of the apps' URLconf

app_name = "homepage" # pylint: disable=invalid-name

urlpatterns = [

path("", views.index, name="index"),

]

For our homepage application to be served, we must register it in a different urls.py file:

# src/hello_visitor/urls.py

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import include, path

urlpatterns = [

path("", include("homepage.urls")),

path("admin/", admin.site.urls),

]

Our project’s base HTML template will live in a new file, src/templates/layouts/base.html:

<!DOCTYPE html>

{% load static %}

<html lang="en">

<head>

<!-- Required meta tags -->

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<!-- Bootstrap CSS -->

<link href="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/bootstrap@5.0.1/dist/css/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet" integrity="sha384-+0n0xVW2eSR5OomGNYDnhzAbDsOXxcvSN1TPprVMTNDbiYZCxYbOOl7+AMvyTG2x" crossorigin="anonymous">

<title>Hello, visitor!</title>

<link rel="shortcut icon" type="image/png" href="{% static 'favicon.ico' %}"/>

</head>

<body>

{% block main %}{% endblock %}

<!-- Option 1: Bootstrap Bundle with Popper -->

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/bootstrap@5.0.1/dist/js/bootstrap.bundle.min.js" integrity="sha384-gtEjrD/SeCtmISkJkNUaaKMoLD0//ElJ19smozuHV6z3Iehds+3Ulb9Bn9Plx0x4" crossorigin="anonymous"></script>

</body>

</html>

We’ll extend the base template for our homepage app in a new file, src/templates/homepage/index.html:

{% extends "layouts/base.html" %}

{% block main %}

<main>

<div class="container py-4">

<div class="p-5 mb-4 bg-dark text-white text-center rounded-3">

<div class="container-fluid py-5">

<h1 class="display-5 fw-bold">Hello, visitor {{ visit_counter.count }}!</h1>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</main>

{% endblock %}

The last step in creating our UI is to tell Django where to find these templates. Let’s add a TEMPLATES['DIRS'] dictionary item to our settings.py file:

# src/hello_visitor/settings.py

TEMPLATES = [

{

...

'DIRS': [BASE_DIR / 'templates'],

...

},

]

Our user interface is now implemented and we are almost ready to test our application’s functionality. Before we do our testing, we need to put into place the final piece of our environment: static content caching.

Our Static Content Configuration

To avoid taking architectural shortcuts on our development system, we’ll configure static content caching to mirror our production environment.

We’ll keep all of our project’s static files in a single directory, src/static, and instruct Django to collect those files before deployment.

We’ll use Toptal’s logo for our application’s favicon and store it as src/static/favicon.ico:

# from `src` folder

mkdir static

cd static

wget https://frontier-assets.toptal.com/83b2f6e0d02cdb3d951a75bd07ee4058.png

mv 83b2f6e0d02cdb3d951a75bd07ee4058.png favicon.ico

Next, we’ll configure Django to collect the static files:

# src/hello_visitor/settings.py

# Static files (CSS, JavaScript, images)

# a la https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/3.2/howto/static-files/

#

# Source location where we'll store our static files

STATICFILES_DIRS = [BASE_DIR / "static"]

# Build output location where Django collects all static files

STATIC_ROOT = BASE_DIR / "staticfiles"

STATIC_ROOT.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

# URL to use when referring to static files located in STATIC_ROOT.

STATIC_URL = "/static/"

STATICFILES_STORAGE = "whitenoise.storage.CompressedManifestStaticFilesStorage"

We only want to store our original static files in the source code repository; we do not want to store the production-optimized versions. Let’s add the latter to our .gitignore with this simple line:

staticfiles

With our source code repository correctly storing the required files, we now need to configure our caching system to work with these static files.

Static File Caching

In production—and thus, also in our development environment—we’ll use WhiteNoise to serve our Django application’s static files more efficiently.

We register WhiteNoise as middleware by adding the following snippet to our src/hello_visitor/settings.py file. Registration order is strictly defined, and WhiteNoiseMiddleware must appear immediately after SecurityMiddleware:

MIDDLEWARE = [

'django.middleware.security.SecurityMiddleware',

'whitenoise.middleware.WhiteNoiseMiddleware',

# ...

]

STATICFILES_STORAGE = 'whitenoise.storage.CompressedManifestStaticFilesStorage'

Static file caching should now be configured in our development environment, enabling us to run our application.

Running Our Development Server

We have a fully coded application and can now launch our Django’s embedded development web server with this command:

# in the `src` folder

python manage.py runserver

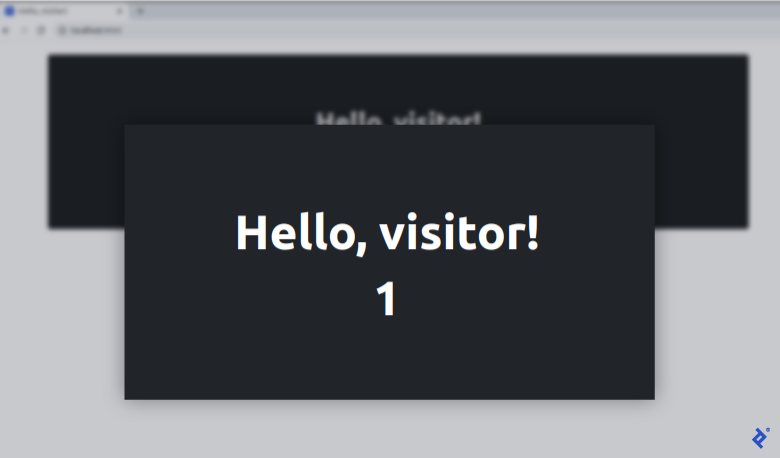

When we navigate to http://localhost:8000, the count will increase each time we refresh the page:

We now have a working application that will increment its visit count as we refresh the page.

Ready To Deploy

This tutorial has covered all the steps needed to create a working app in a beautiful Django development environment that matches production. In Part 3, we’ll cover deploying our application to its production environment. It’s also worth exploring our additional exercises highlighting the benefits of Django and pydantic: They’re included in the code-complete repository for this pydantic tutorial.

The Toptal Engineering Blog extends its gratitude to Stephen Davidson for reviewing and beta testing the code samples presented in this article.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- High-performing Apps With Python: A FastAPI Tutorial

- Streamline Your Django Settings With Type Hints: A Pydantic Tutorial, Part 1

- Top 10 Mistakes That Django Developers Make

- A Guide to Performance Testing and Optimization With Python and Django

- Security in Django Applications: A Pydantic Tutorial, Part 4

Understanding the basics

How fast is pydantic?

Out of the box, pydantic is faster than other validation libraries. There are published benchmarks available in the official pydantic documentation.

Can I use pydantic with Django?

Yes. Pydantic is a regular Python package and can be used with Django simply by installing it with pip.

Which environment is best for Django?

We define “environment” as the system where our application is developed or hosted. In this case, the best development environment is defined as one that matches what is being used in production.

Why are there separate development and production environments?

User-facing websites should always run in a secure environment that is updated with new code only after the new code has been tested extensively. New code is created in a separate development environment and often tested in one or more staging environments before it is deployed to the production environment.

Arjaan Buijk

Plymouth, MI, United States

Member since June 4, 2018

About the author

Arjaan is a senior engineer and data scientist who creates mission-critical cloud solutions focused on Rasa for international banks and insurance companies. He architects and teaches large-scale Kubernetes solutions.

PREVIOUSLY AT