Evolving UX: Experimental Product Design with a CXO

Chris Gibbins, chief experience officer (CXO) at Creative CX, explains how design experimentation can help businesses deliver better products, boost conversion, and increase revenue.

Chris Gibbins, chief experience officer (CXO) at Creative CX, explains how design experimentation can help businesses deliver better products, boost conversion, and increase revenue.

Miklos is a UX designer, product design strategist, author, and speaker with more than 18 years of experience in the design field.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Integrating a culture of continuous experimentation into the product design process is essential for elevating user experiences and boosting a company’s bottom line. Instead of converging on one solution, implementing it, and later evaluating it, experimental product design builds a variety of solutions to quickly determine which one works best.

To explore how to improve user experiences through experimental product design, we spoke to Chris Gibbins, a chief experience officer (CXO) at Creative CX, an insight-led, advanced experimentation consultancy based in London. Chris is a human-centered design/UX professional with more than 20 years of experience who has spoken about experimentation at many events and conferences.

What Is Experimental Product Design?

Chris: Experimental product design is about taking the scientific method of experimentation used for many years in medicine, agriculture, and other disciplines and applying it to optimize experiences in digital product design. It typically involves testing different content and interface elements for effectiveness: headlines, imagery, layout, colors, buttons, and other components. However, it’s not just for small UX refinements, companies also use it to test the redesign of entire user journeys, new features, and even back-end functionality.

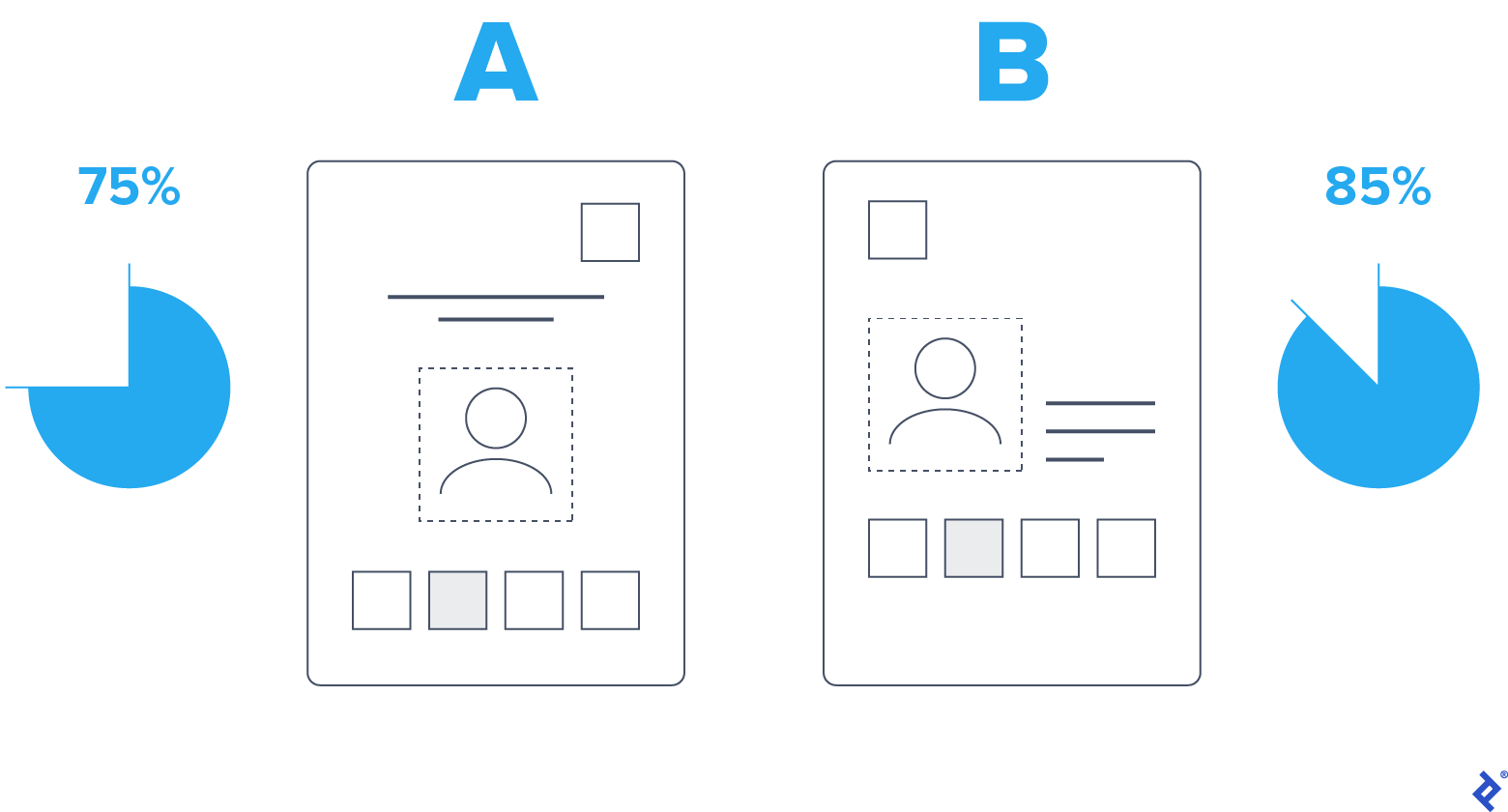

The key principle behind experimentation is about proving or disproving a hypothesis with the scientific method. It’s about refuting that the difference we see between two versions of a design has anything to do with luck. Rather than relying on correlation, it’s about causation. Using measurements, we learn whether a specific design is statistically better than another. Can we be 70% or 95% sure? The stats will give us the answer.

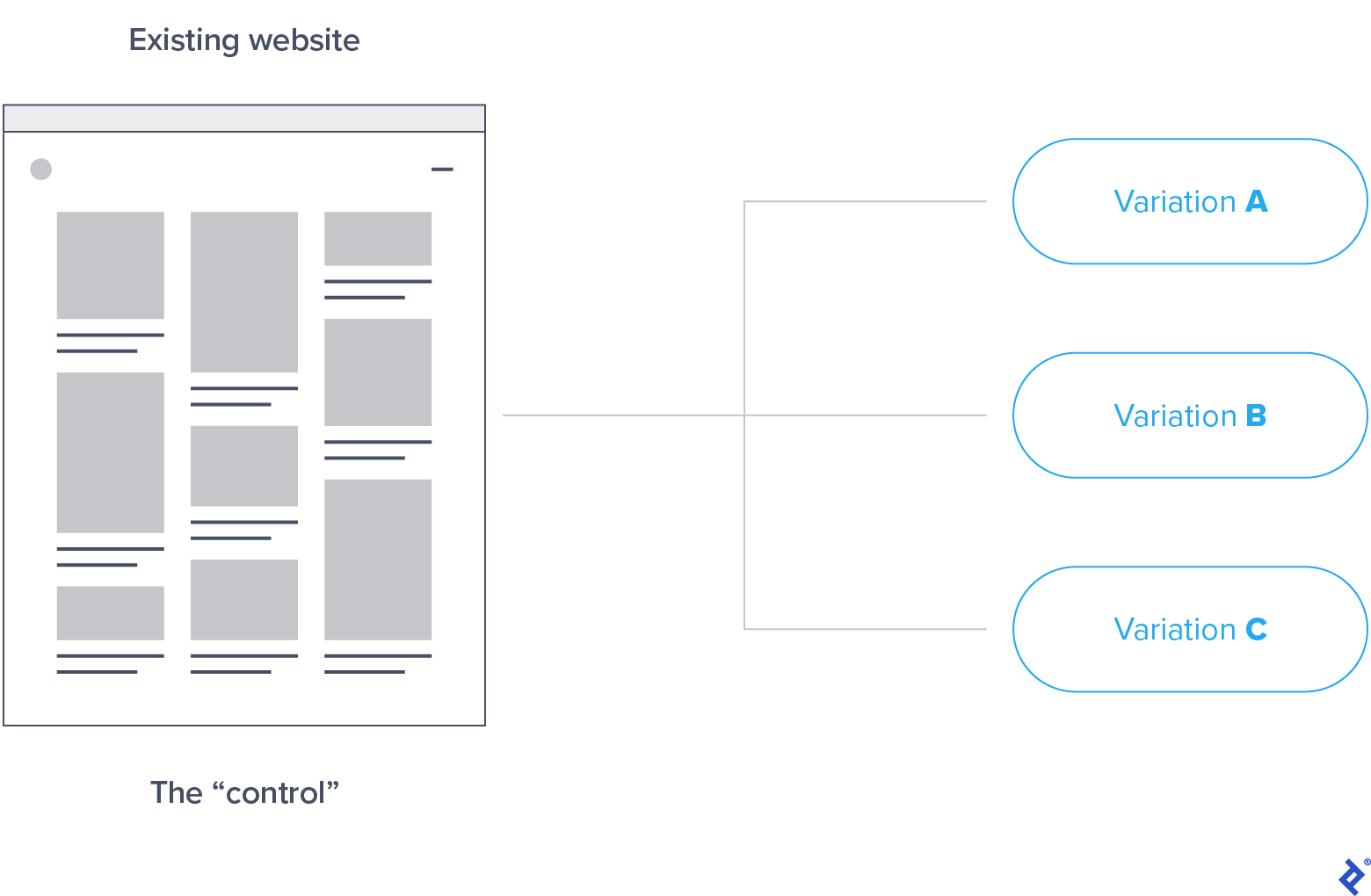

Experimental product design is performed as a randomized experiment with a control, the design’s current state. As the test is run, we compare new design variations against the control using A/B/n tests or multivariate tests. The control ensures the reliability of the results by comparing its measurements with the variations’. Simply put, experimentation is about quantifying how people respond to a change in a design. It could be as small as changing an icon, or as big as a redesigned checkout process.

The intent is to make better decisions regarding design improvements and find out quickly which design solution works and why. All product designs are based on hypotheses and ideas that may end up not working. If assumptions are not tested, designers don’t learn what works and what doesn’t so they will stick to a particular way of doing things, often touting it as coming from “best practices” and their years of experience.

What Is the Value of Experimental Product Design?

Chris: The digital domain is a great environment to apply the scientific method of experimentation because it’s a lot easier to do than in the real world. It takes some time to set up an experiment, but with some of the new tools, we can gain deeper insights more quickly by tracking people’s behavior. This accelerated process quickly boosts UX, and the results also yield quantifiable business metrics.

During an experiment, we would typically test three or four variations of the design. If we have three variations, 25% of traffic goes to the control (the current website), 25% goes to variation one, 25% to variation two, and 25% to variation three.

Performing A/B/n tests (several variations) is preferred vs. just doing A/B tests (single variation) because the former gives us more creative freedom to be “experimental.” For example, one of the variations can be a wild card idea, which won’t necessarily have the desired result right away but might take us in a different direction and open up new opportunities.

Because of this, we can think in two ways about the value of experimentation in design. One, where we’re looking to measure effectiveness: whether a design performs better vs. another. Two, where we can use it as a creative playground to try out unusual ideas.

Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per month, per week, and per day… Jeff Bezos

What Are Some Experimental Design Examples?

Chris: Through experimentation, we’ve had a lot of success by making user tasks easier and faster to complete, which also impacted the companies’ bottom line.

During a recent usability-testing project, we analyzed the effort it took for people to navigate a mobile site with a hamburger menu. It took a while for them to discover the menu, three to four clicks to find the correct category, and then get to the products. That seemed like too much effort—extra “cognitive load” in UX parlance.

After writing the customer problem statement and conducting an ideation session, we ran an online experiment. First, we A/B tested improvements to the hamburger menu by adding a “menu” label. Second, we tried a more radical design change introducing a horizontal scrolling menu across the top to ease navigation. The results showed that the design variation with the horizontal scrolling menu significantly improved the number of people getting to the product pages more quickly and making a purchase.

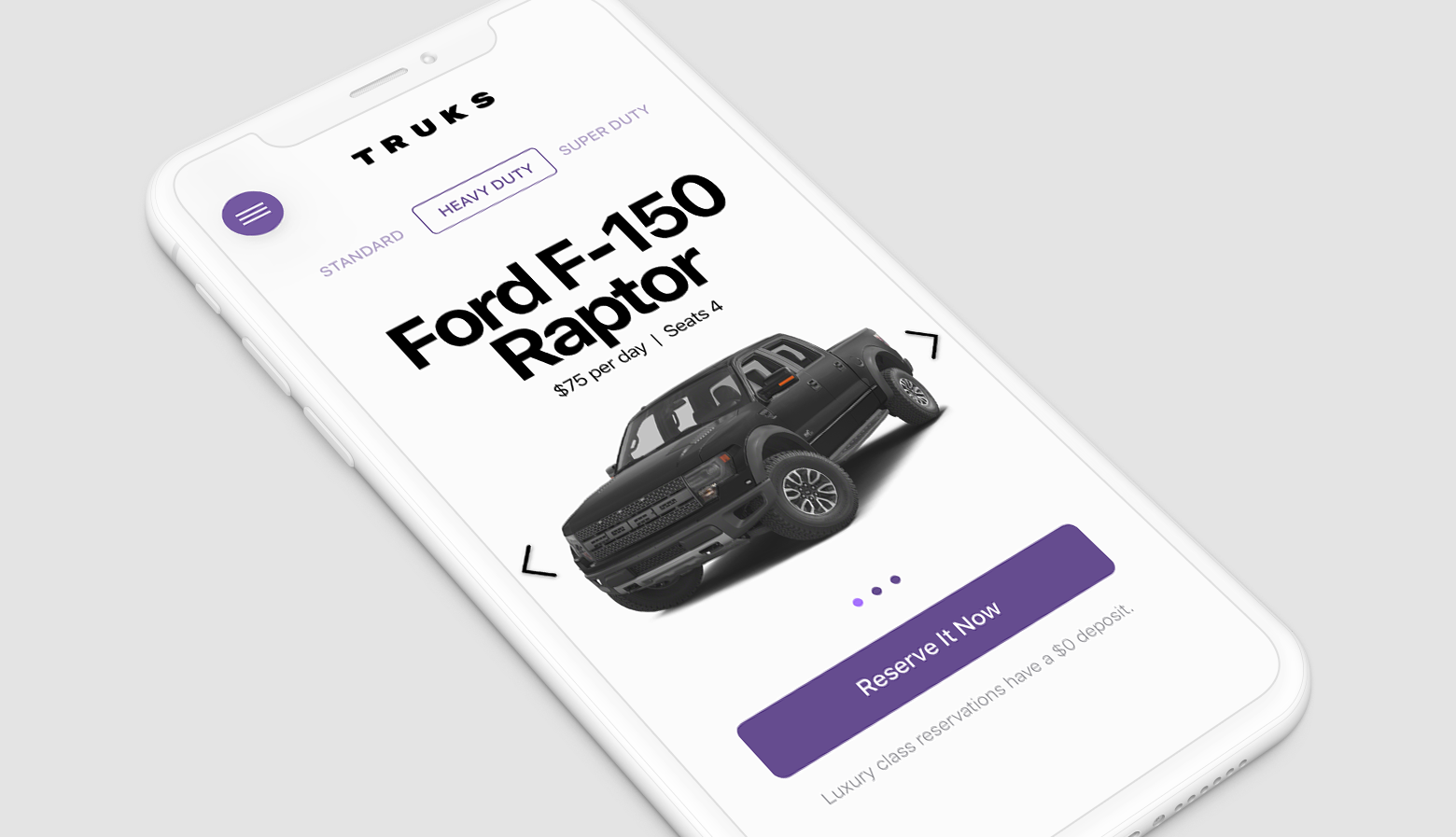

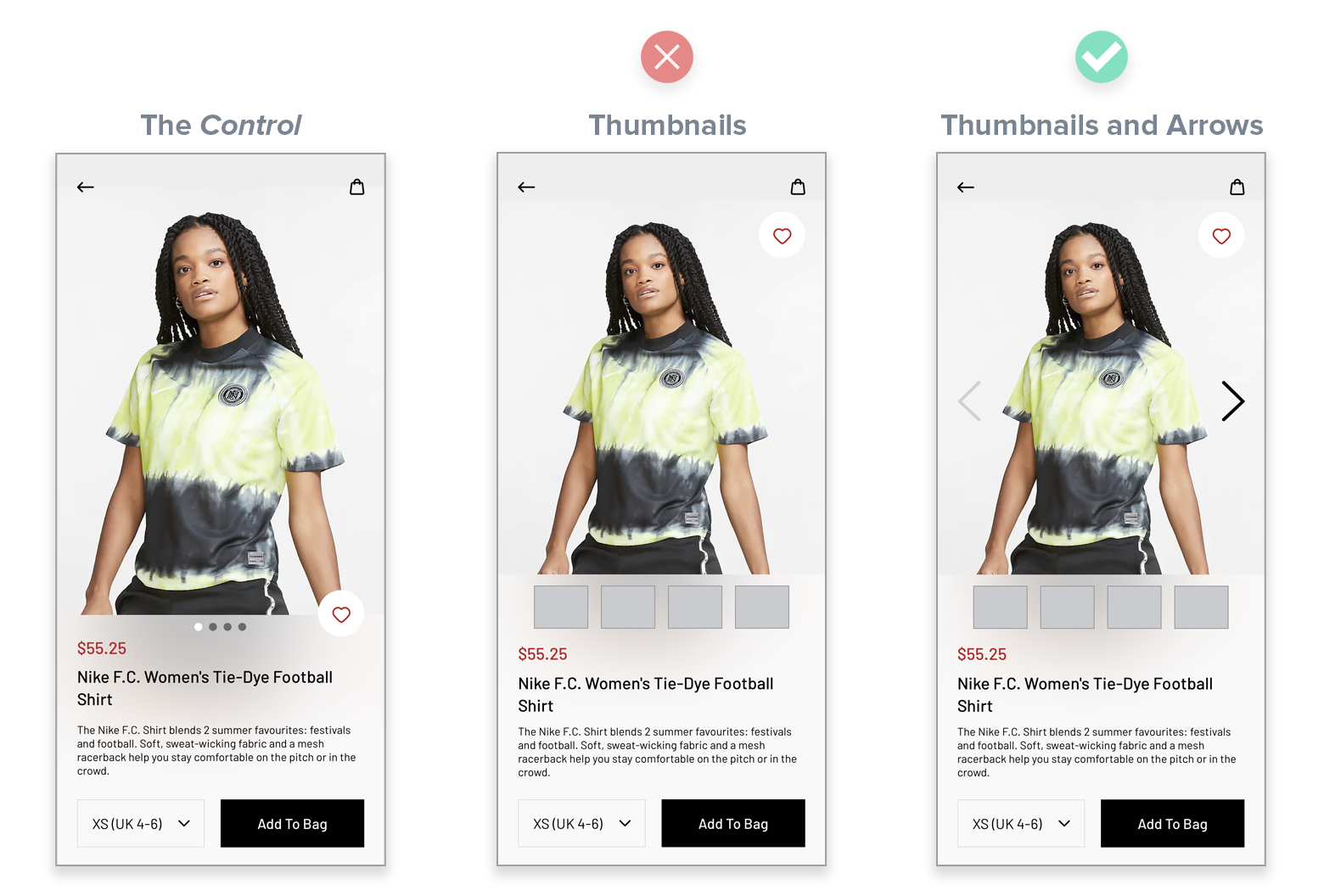

On another recent eCommerce mobile project, we found that despite the designers’ assumptions that everybody knows how to swipe on things, this wasn’t the case when it came to the product image gallery on mobile. They put six small dot indicators (sometimes called “pips”) under a product image to indicate that multiple photos were available. Image carousel dot indicators are a common mobile UI pattern, but even so, customers weren’t interacting with the photos the way designers wanted them to.

We were wondering, “How come everyone’s interacting with the product photos on the desktop, but not on mobile? Many people on mobile are not doing it at all, and maybe that’s one of the reasons why the mobile conversion rate is so low.” Perhaps it’s because they can’t decipher what those little dots mean or that they are just not obvious enough. Some people don’t necessarily understand the UI pattern signifying “swipe for more photos.” As product photos are critical to users when shopping online, this was a serious customer problem that needed solving.

To find a solution, we tested three design variations. For variation one, we put left and right arrows next to the images to signal the availability of more pictures. The theory was that they would signify “swipeability” for those who are not familiar with it.

For variation two, we added thumbnails under the images on mobile so that users could get a preview of the other images available even though they were a little small. Variation three combined both these changes and included thumbnails and arrows, which we thought could be a little too cluttered for users but still worth testing. To our surprise, the thumbnails and arrows version won. The data showed that it massively improved how people interacted with product images.

We saw a 30% increase in people engaging with product images due to these design changes, and we also saw a significant increase in conversion rates, which increased the company’s revenue. As a side note, the other two design variations were also successful, however, not as much as variation three. All we did was make the user experience better through design experimentation. Some designers may object to some of these options for aesthetic reasons, but it works. As designers, our job is to improve the UX for customers and provide value to the businesses.

What Is a “Fake Door” Test?

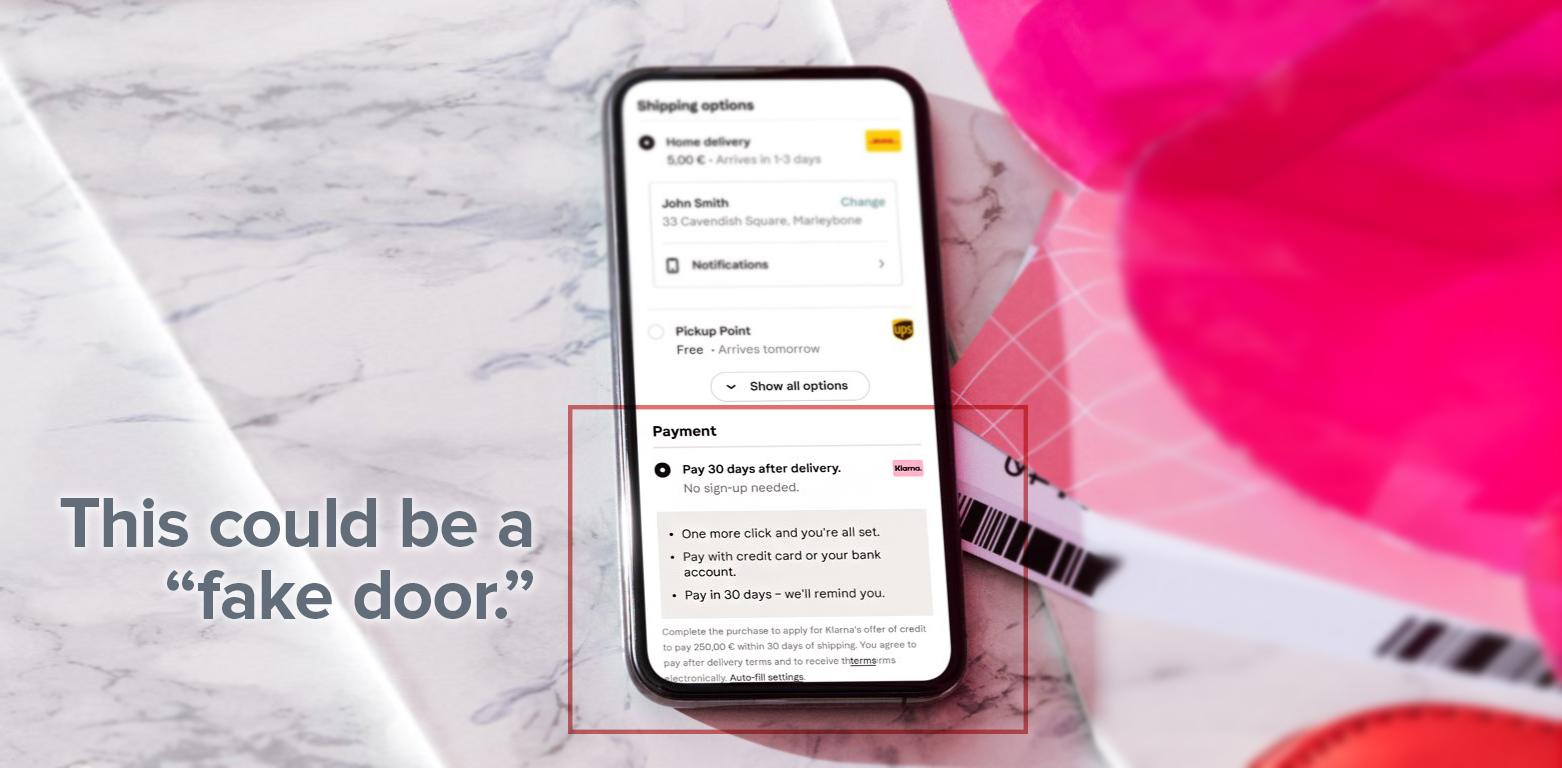

Chris: The “fake door,” aka the “painted door,” test displays something in a product that resembles a feature and measures how people engage with it. The fake door method is about testing something before you build it. It can be used to evaluate new product features, new business ideas, or even new services.

We know that building new product features and testing them comes with a tremendous cost. It could be a high-risk feature that product teams want to explore. For example, building out a brand new service on an eCommerce site involves not only the front-end but the back-end infrastructure. The company may also need to think about the entire service design behind it: customer service and technical support.

A painted door test is similar to the Wizard of Oz type experimentation method where “you fake it before you make it.” We would design the minimum representation of a feature, such as introducing a new payment method during checkout. We would then put it in front of a segment of users, test it, and gather feedback. After the “pretend feature” goes live, designers can observe what’s happening with the design through measurements.

This type of testing is a bit controversial and has to be handled delicately. We have to manage disappointments carefully because it’s not a working feature. When people click on it, we have to put up a friendly message that says, “Thank you for your interest. This feature is not quite ready, but it’s something we’re considering.” Optionally, we can follow on with a question: “Is this something you would use?” If measurements show a positive response, the company can decide to build it.

Is Experimental Product Design the Same as Data-driven Design?

Chris: Experimental design, by its nature, is primarily quantitative. We may A/B test dozens of designs, look at the data, and pick the highest-performing one. That’s all data-driven decision-making.

That said, these days, experimental product design is crossing into the qualitative realm. We can track scrolling and other types of interaction with every element in a UI. Through clickstream analysis, we can observe a change in behavior, what people might be thinking. When they scroll the page, they click something, they swipe an image; if that’s all tracked, we can see the good and the bad as if “through their eyes” in the data. It’s not purely quantitative. It incorporates behavioral insights.

These days, we also have highly sophisticated tools such as computer vision-powered AI analysis that can pinpoint hesitation, detect frustration on faces, and listen for disappointment in people’s voices. We can then combine the quantitative data with the qualitative to get super-rich insights into product usage.

Why is behavioral analysis with quantitative data valuable? It fills in the gaps. Typically, we can observe some crucial things during in-person testing: people hesitating, or when they slip up. In remote, moderated usability testing, for example, we get the chance to ask follow-on questions or set a follow-on task. It’s not something we can generally do with experimentation. However, if we can overlay behavioral data with other data types, our insights can go deeper.

It can be quite astounding to observe things like “rage clicks,” for example, with session recording tools. It allows us to go beyond cold, hard data. We can see how people get frustrated or angry when they get stuck. We can observe it through erratic mouse movement or repeated clicks on the same thing. Something isn’t working, and we can learn from that.

Every day, we run thousands of concurrent experiments to quickly validate ideas. Experimentation has become so ingrained in Booking.com’s culture that every change from entire redesigns to infrastructure changes is wrapped in an experiment. Booking.com

What Tools Can Designers Use for Experimentation?

Chris: There are two types of experimentation tools companies tend to use: off-the-shelf tools, such as Optimizely, Monetate, Qubit, Google Optimize, VWO, Adobe Target, and AB Tasty, and custom tools that many develop.

Some companies such as Booking.com—famous for their experimentation—built the testing tools and integrated them with their system. For them, it pays off because they’re such a vast organization. Facebook, Google, and Amazon also have custom tools, of course, but most experimental product designers use ready-made tools.

Experimentation tools are evolving and getting better all the time. Next-generation session recording tools like Smartlook, SessionCam, Contentsquare, and Hotjar provide useful, rich data with sophisticated UIs. Tools like these can help enhance our experimentation as they provide a greater level of insight into how users interact with each design variation. They help product teams get a better understanding as to why certain designs are better or worse and can help with follow-on iterations.

99% of all innovations at Amazon are incremental. Jeff Bezos

How Can Designers Take Advantage of Experimental Product Design?

Chris: Experimentation is a powerful design technique that can be easily integrated into the design process. It’s similar to the “How-Might-We” method in design thinking—an important part of the ideation process. By asking how might we solve this problem?, designers can experiment with a dozen designs to hone in on the one that works.

Designers tend to think about design as being about layouts and color schemes, cool typography, skilled use of negative space, balance, and other visuals. All of that is important, but the design has to work for the customer and the business.

Through the experimentation process, customer actions and task completion decide which design works best. If we’re monitoring the right metrics, such as progression through the site, increasing the number of product images viewed, and business metrics such as conversion rate, revenue, and average order value, we’re in effect tracking what matters most to the user and the business. After all, a user completing the task they came to the site to do is the critical metric that should matter the most to UX designers. For example: How easy was it for a customer to find the store locator? Was the checkout flow as friction-free as possible?

Smart business people learned a long time ago, “what’s good for the customer is usually good for the business.” In the case of an eCommerce site, it’s about making shopping easy and giving customers detailed information about a watch, a shoe, or a luxury bag that’s relevant to them. The next goal is to make it fast and easy to complete the purchase. To do that, we need to remove any friction, which is what experimentation excels at. That part is very much about getting people through the funnel efficiently and helping them complete their end task of buying the product.

In an increasingly digital world, if you don’t do large-scale experimentation...you’re dead. Mark Okerstrom, CEO of Expedia

Does Experimental Product Design Kill Creativity?

Chris: This is a notion that comes up frequently. Recently, I heard a heckler at a conference where the speaker was talking about data-driven design and experimentation. He shouted, “How can you be creative when you have numbers telling you what you should do?” He believed that looking at numbers kills creativity.

It’s quite the opposite. It amplifies the effectiveness of what we do. It boosts creativity because we can allow ourselves to design “outside the box.” Not only zero in on the most effective design but test wild card ideas. The radically creative design may prove to be the winning one that converts many people or brings in more revenue. We can push the boundaries because we have the safety net of experimentation. Instead of following everyone else (or copying), we can use experimentation to help empower organizations to innovate and lead the way.

The experimental design process is an unconventional mindset that may be challenging to adopt. Most designers are used to converging on a single solution after UX research and producing various UX artifacts. They craft the final design, which goes through implementation. Later, the product team measures it to see if it’s better than the previous one and whether all the effort was worth it. With experimental product design, we risk a lot less and find out much sooner what works.

It’s worth noting that being creative isn’t always about adding things. It can be about removing them. Designers may say, “Look, we can adjust the layout” or “What if we removed this element?” Some experiments with excellent outcomes may result from having removed clutter from a site or a mobile app to simplify the experience.

Still, we must acknowledge that pushing things to the extreme in a creative way can be risky. When we experiment, it’s vital to test a small batch and “not bet the farm” on anything. For a company that’s making millions of dollars a week, for example, it’s too risky to go with your gut and launch designs without running a controlled online experiment. If it’s not working, we can revert to the original design instantly. All big eCommerce and social media brands conduct design experiments in this way.

One of the things I’m most proud of, and what I think is the key to our success, is a testing framework we built. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook

Summary

Experimental design sharpens the design process and helps designers craft the most effective solution. It allows designers to make better decisions because they can discover more quickly whether something works or not. It also serves companies better by driving business metrics that matter.

Small design changes can have a big impact. Many of the world’s most successful brands practice experimental product design. These brands recognize that blending rigorous design with creativity, innovation, and experimentation is essential for their growth.

However, in order to optimize customer experiences and maximize business value, the culture of experimentation needs to be cultivated and integrated into product teams. Business stakeholders may need to get on board, but once the metrics show positive results, it shouldn’t take much convincing. They will realize that experimentation is instrumental to businesses delivering better-designed products, converting more customers, and boosting revenue.

Let us know what you think! Please leave your thoughts, comments, and feedback below.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is meant by experimental design?

Experimental product design is about incorporating continuous innovation and experimentation into the product design process to improve a product’s user experience. Testing various designs helps designers make better decisions because they are able to quickly find out whether something works.

What is the purpose of an experimental design?

The purpose of experimental design is to use data to inform design decisions. Instead of converging on one solution, implementing it, and evaluating it later, experimental product design allows designers to continuously build various solutions and find out quickly which one works best.

What are examples of experimental design?

In 2012, a Microsoft employee had an idea about changing the way Bing displayed ad headlines. They A/B tested the idea, and the change increased revenue by 12%. Jeff Bezos said that at Amazon, “99% of all innovations are incremental” and that Amazon relies on experimentation methods to arrive at the best designs.

Is UX design dying?

UX design is not dying. It’s evolving. The term “UX design” may increasingly morph into “product design” as the natural evolution of UX design. The name will adjust as the discipline encompasses additional aspects of the customer experience (CX) and integrates more business value-driven characteristics.

Is UX a growing field?

Industry trends indicate that UX design is still a growing field. Businesses everywhere increasingly require customer-centric design strategies for their products and services. Consequently, UX professionals are in high demand worldwide, especially in the United States, Europe, UK, Canada, and Australia.

Miklos Philips

London, United Kingdom

Member since May 20, 2016

About the author

Miklos is a UX designer, product design strategist, author, and speaker with more than 18 years of experience in the design field.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT