Art vs Design – A Timeless Debate

Two Toptal designers engage in a lively debate about aesthetics, objectivity, and the definition of art and design.

Two Toptal designers engage in a lively debate about aesthetics, objectivity, and the definition of art and design.

Miklos is a UX designer, product design strategist, author, and speaker with more than 18 years of experience in the design field.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Spend any amount of time working among professional designers and you learn that equating art with design is a surefire way to stir the pot and hear bold statements like:

- “Design is not art. Design has to function.”

- “Art is meant to provoke thought and emotions, but it doesn’t solve problems.”

- “Artists primarily work off instinct, whereas designers employ a methodical, data-driven process.”

Unfortunately, the designer vs. artist discussion often deteriorates into ranting and raving. Lines are drawn, battle flags are raised, and productive dialogue becomes impossible.

What’s really going on here? Why have art and design been pitted against each other, and why are designers so adamant that design cannot be art? These questions are the starting point for a thoughtful conversation between Toptal designers Micah Bowers and Miklos Philips.

Bowers is a brand designer and illustrator who believes that art encompasses many creative disciplines, design being one, and therefore design is art.

Philips, a UX designer and lead editor for the Toptal Design Blog, takes the position that art and design may intersect, but they are distinctly different fields.

With our contestants in the ring, it’s time for the debate to begin. Gentlemen, touch gloves and go to your corners.

What Is Design in Art?

Micah: Design is art. Art is design. No exceptions.

Let’s be clear—I’m aware of how unpopular my position is, especially among my design peers. I’ve been to talks, read books, spoken with colleagues, and taken classes determined to establish the irreconcilable differences between art and design. Whenever I share my views, the art design backlash comes quick and fierce, but I remain unmoved by the counter-arguments (good luck, Miklos).

The insistence on a distinction between art and design has been like a constant, low-grade fever that’s bothered me for the last 15 years—first through my industrial design training, then during a fine arts graduate degree, and on into my career in branding and illustration.

My position is this: Great design is first and foremost art. What is this belief rooted in? A philosophical understanding of art.

Design’s definition in art is steeped in centuries of debate. Greek philosopher Plato believed that art is essentially a reflection of a reflection of what is real. But his views are widely contested, and since we have to start somewhere, we must aim for an understanding that acknowledges history and the diversity of global thought and culture.

Paraphrasing the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy leads us here:

Art exists and has existed in every known human culture and consists of objects, performances, and experiences that are intentionally endowed by their makers with a high degree of aesthetic interest.

By virtue of this definition, design is undeniably art. It can be found in every human culture. Designing art creates objects, performances, and experiences. And, designers intentionally instill significant amounts of aesthetic interest into their work.

Here, the inevitable cry is heard, “Wait! You’ve undone yourself by a single word. Aesthetic!”

Designers love to make sweeping assumptions in regard to aesthetics, so allow me to construct a safeguard.

Much like art, the concept of aesthetics is a complicated field of philosophical thought and cannot be reduced to the designer stereotype that it means “making things look pretty.”

In fact, aesthetics covers many questions that are essential to the “art vs. design” debate:

- “Is it possible to determine an aesthetic judgment from a practical one?”

- “What is the basis by which we judge between utility and beauty?”

- And, “How are the foundational beliefs by which we make aesthetic judgments influenced by time, culture, and life experience?”

Here’s my point: In the world of contemporary design, art has been narrowly defined and unfairly diminished into a pathetic, watercolor caricature. Designers have flippantly inflated the significance of their own disciplines (which vary in substance to a comical degree) over centuries of artistic practice, philosophical inquiry, and cultural understanding. Design is art. Art is design. No exceptions.

Miklos: Design needs to fulfill a function. Not art.

First of all, we have to separate out what type of design we’re talking about. I can see in the case of graphic design, illustration, and branding maybe design is somewhat “art,” but if we’re talking about more functional design—such as digital product design or industrial design—we need to go a lot deeper, and it becomes clear: Design is not “art.”

Great design is part science, part process, and part a practical set of solutions with a dash of aesthetics thrown in. Going beyond the surface, a designer inevitably discovers that great design is more about delivering solutions to problems.

Design is a process, not art.

As a UX designer, I always need to dig deeper, beyond the facade that one might call a potential “design” and look at the bigger picture holistically: the target audience, the use case scenarios, the context, and the device the design is intended for: TV to mobile, desktops to tablets, to ATMs, etc. And when it comes to product design, let’s not forget validation and usability testing. If design were just art, how could you test it?

If design were purely about art, what about usability heuristics? Are such UX usability concepts as feedback, consistency and standards, error prevention, user control, flexibility, and predictability out the window? Isn’t design there to serve people? If you want to be an artist, be that, but don’t call yourself a designer. Be a painter or a sculptor.

“There is beauty when something works and it works intuitively,” says Jonathan Ive.

The “working intuitively” part alone can’t be achieved by “art”; it’s driven by user research and testing. Good design is also data-driven. What is more, in the near future, AI will transform the way design is delivered. It will be super-personalized and anticipatory. Will design as “art” be able to do that? I don’t think so.

You can’t say designing a ticket vending machine UI is “art.” Surely, aesthetics and emotional design come into play—as other articles on the Toptal Design Blog have mentioned before—because aesthetics play a role in design to the extent that designs with better aesthetics make a product seem to “work better.” But still, the function of the design and context of use need to be taken into account.

For example, in Don Norman’s seminal book “The Design of Everyday Things,” he talks about design and the concept of affordances. (The concept of an affordance was coined by the perceptual psychologist James J. Gibson in his groundbreaking book The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception.) Norman writes:

Affordances provide strong clues to the operations of things. Plates are for pushing. Knobs are for turning. Slots are for inserting things into. Handles are for lifting. Balls are for throwing or bouncing. When affordances are taken advantage of, the user knows what to do just by looking: no picture, label, or instruction needed.

So, affordances are “perceived properties” of a function in design, and they need to be signaled to the user with “signifiers,” which provide clues to the user of the existence of a possible interaction. I don’t know how one would go about marrying the concepts of affordances and signifiers with “art.” They are essential interaction design concepts in the realm of HCI (human-computer interaction). They have nothing to do with art.

As a UX designer, I reject the notion. I mean, can you imagine a ticket vending machine designed in the cubist style by Picasso? Not saying it wouldn’t be interesting, but it wouldn’t be very effective or functional.

What Is Good Design?

Micah: Art solves problems. “Good design” is simply one path to a solution.

A ticket vending machine in Picasso’s Cubism? Now that would be good, artistic design! I can envision the hands of a capable artist leveraging Cubism’s stylistic dissonance into a clearly defined visual hierarchy that delights users with unambiguous points of interaction. Finally, we could wave goodbye to the bland and confusing button shrines we’ve all grown accustomed to.

Interestingly, such an idea is not without precedent. In towns and cities around the world, public art installations have been used to improve experiences previously overlooked or muddled by design. The Van Gogh Path, created by Dutch artist Daan Roosegaarde, is a perfect example.

Inspired by Van Gogh’s Starry Night, the path runs through Nuenen, NL (a town where the artist lived in the 1880’s) and is made up of thousands of small painted rocks that capture energy from the sun during the day and light up at night.

If this were all the project encompassed, it would be little more than a nice lighting effect, but the scope of Roosegaarde’s artistic vision is much wider. Van Gogh Path is a proof of concept within a larger project called SMART HIGHWAY, an ambitious effort aimed at reinventing the Dutch landscape by implementing a sustainable system of glowing, interactive roads.

The takeaway? Art and artists have the ability to solve substantial problems.

Problem solving requires knowledge, experience, skill, research, risk, and an understanding of human behavior, but unfortunately, many designers fail to acknowledge that artists employ problem-solving methodology in their work—even though artists have been systematically pursuing creative solutions for centuries, long before the distinction of “designer” was fashionable.

Need proof?

Again, we look to a Dutch artist, the master of light and painter of the Girl with a Pearl Earring, Johannes Vermeer. Vermeer lived during the middle part of the 17th century, experienced modest success as a painter, and died under a mountain of debt. Nearly two centuries after his death, however, Vermeer’s work was rediscovered, and his standing as one of the great painters of all time was cemented in the annals of art history.

But a strange thing happened. The more people studied Vermeer and his work, the more they realized that his paintings and process were truly unlike any other artist’s. How so?

- Vermeer had no formal artistic training and apparently did not undergo an apprenticeship as a painter.

- His body of work is quite small, consisting of less than 50 total paintings.

- He never had any pupils or apprentices of his own.

- Nearly all of Vermeer’s paintings were staged in one of two rooms in his home.

- There are no surviving preparatory drawings or sketches attributed to Vermeer.

- X-rays of Vermeer’s paintings reveal no underdrawings or compositional corrections.

- His paintings contain lighting and perspective distortions that can only be seen through manmade lenses.

- And finally, Vermeer was a close friend of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch scientist known for his trailblazing work in the fields of lens making and microscopy.

What does all this mean? Vermeer likely used an advanced, and still unknown, form of camera obscura to create his masterpieces. This is a contentious theory, but there is ample evidence from multiple sources to support such a claim.

How is it relevant to our debate? Vermeer invented an apparatus and process that went undetected and unduplicated for over 350 years and allowed him to create some of the world’s most iconic and technically exquisite paintings without any formal training. That is the pinnacle of problem solving.

Design is an art form, a method of human expression that follows a system of highly developed procedures in order to imbue objects, performances, and experiences with significance. Like all art forms, design has the potential to solve problems, but there is no guarantee that it will.

More than anything, I want designers to realize that art is not an asinine subculture of design rejects preoccupied with finger painting their feelings. In fact, a low view of art is also a low view of design, science, history, and culture that severely limits creative potential and interdisciplinary progress.

At the end of the day, art solves problems. “Good design” is simply one path to a solution.

Miklos: Good design is unbiased and delivers what people need.

Notice I didn’t say “what people want” like the Rolling Stones song that says: “You can’t always get what you want…you get what you need.” People don’t always know what they want, it’s up to designers to figure out exactly what they need.

By the way, how are paintings solving problems? I fail to see that.

Good design is subjective to a degree, but in my view “good design” is figured out along the way in an iterative design process with lots of validation/testing. It’s “design thinking.” It’s been around for decades. It’s something that just works, where things come together in the right way, at the right time, in the right moment.

Good design is definitely not about art or aesthetics alone. That is just the surface. Good design should be judged by several factors such as the intended user base, the environment, context of use, the medium, and the device it’s to appear on. For example, in the case of a ticket vending machine, aesthetics may not matter as much—people need to get things done and things just need to work for them. It needs to be super functional, fast, and efficient.

Good design in my mind is a design that is balanced in the right way between aesthetics and interaction design. To keep using the example of a ticket vending machine, in that scenario, the “look” is less important and should take the appropriate portion in terms of importance on the balancing scale, and usability and interaction design (functional design) should take the larger proportion.

We could also contrast “good design” vs. “bad design.” Bad design is pandemonium. It is disorder. It can be frustrating or annoying. It slows people down and drains them emotionally. It may actually be ugly, or simply unremarkable and therefore not worthy of anyone’s attention. To your audience, bad design is an impediment instead of an empowerment.

Is Design Subjective or Objective?

Miklos: It’s a mix of both in varying proportions.

Art and design are inextricably combined. I consider design as a holistic endeavor which includes “art.” Design is both subjective and objective but should be primarily objective. Proper design objectivity is achieved by user research (defining the target user base, getting to know the product’s users, observing context of use), working through the essential steps of a user-centered design process (UCD) and user testing.

A design can spring from a brilliant designer’s mind, but its practical use still needs to be validated. If design were only subjective, there would be no need for usability testing (which would most likely upset the designer because he/she would find that the design doesn’t work). The design would come from one person which, to me, is a ridiculous, backward idea. Designers who are 100% subjective are arrogant.

However, a small percentage of subjectivity does come into play—aesthetics play a role, and this is perhaps where emotional design happens. This is the step where the designer’s sensibility, “art,” and subjectivity is brought to the forefront. Great designers “dress up” or “put a facade” on the underlying functional design to create something that works on all emotional levels—visceral, behavioral, and reflective—to deliver a product with amazing UX.

Some designers believe good design must be objective. I don’t believe that. There is a touch of genius in Starck’s or Jonathan Ive’s designs. They bring a dash of subjectivity to their designs which has to do with taste. One of Steve Jobs’s greatest insults was to accuse someone of having no taste.

Micah: Art and all its disciplines (design included) combine objectivity and subjectivity.

I’m not sure how it happened, Miklos, but it looks like we’ve found some sort of common ground, and I’m pleasantly surprised.

Art and all its disciplines, including design, require a mix of objectivity and subjectivity. Of course, there will be designers who roll their eyes and declare, “Art is purely subjective. It can mean different things to different people.” The obvious counterpoint? “Same with design!”

But let’s look closer.

When designers assert that art has to be subjective, they’re typically referring to the way people judge the outcome of an artist’s efforts. This manner of thinking about art places a supreme emphasis on results. In other words, art equals objects, performances, and experiences. Art is a painting. Art is a dance. Art is a light show.

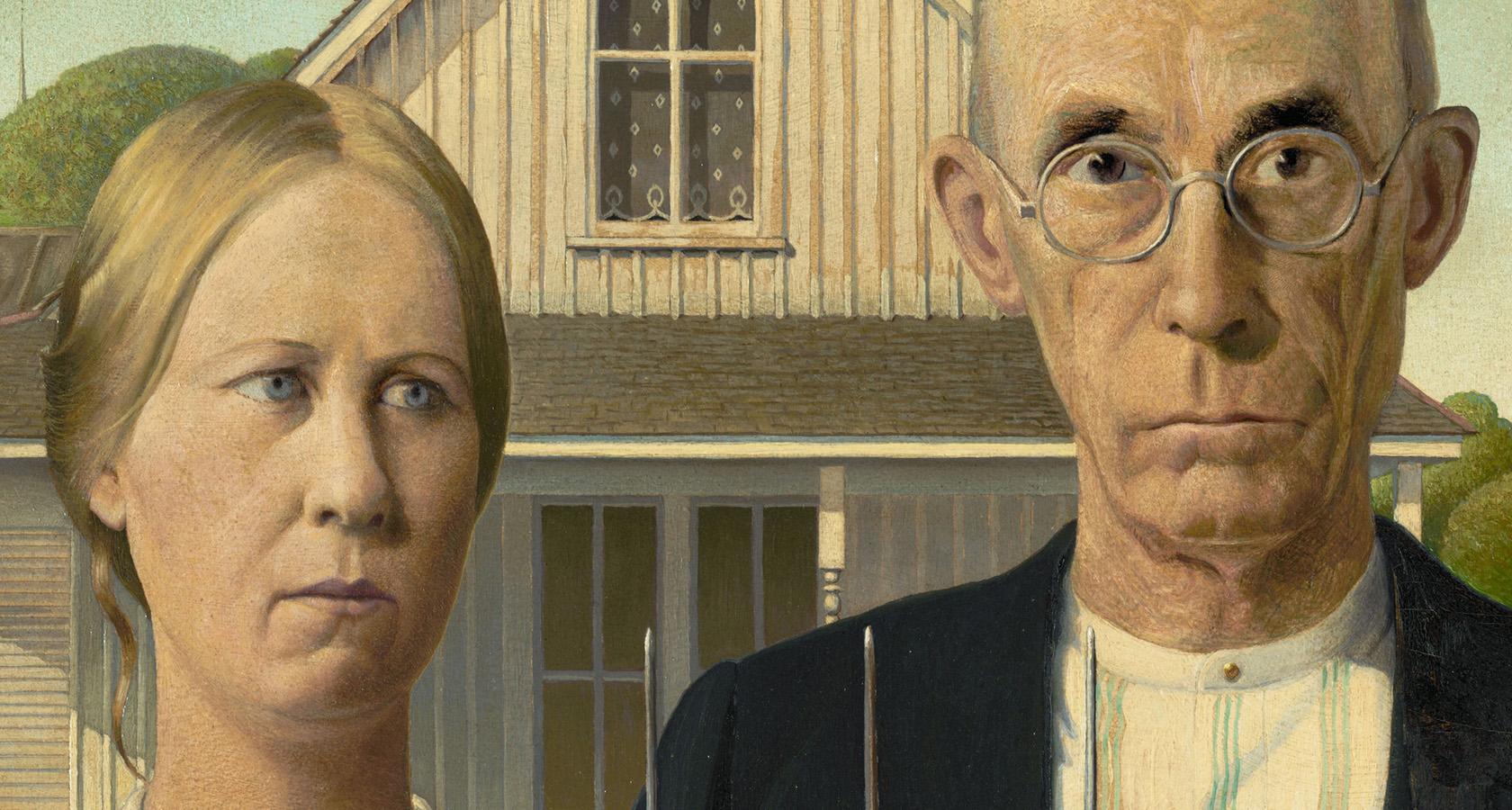

Viewed this way, art is subjective. I think American Gothic is creepy, but you find it inspiring. I think an Eames Chair is classy, but you feel it’s kitschy. I think the WhatsApp interface is confusing, but you’ve never seen anything more elegant. Art is a result, results are open to interpretation, and everyone’s right!

Luckily, the definition of art that I proposed at the start of this debate is more nuanced, so let’s refresh our memories:

Art exists and has existed in every known human culture and consists of objects, performances, and experiences that are intentionally endowed by their makers with a high degree of aesthetic interest.

Notice the words in bold. Artists “intentionally endow” their work with meaning to a high degree. In other words, they consciously enhance or purposefully enrich. There is intent married to action.

Understood more fully, art is not a result. Art is a process, and the process of art is overflowing with objectivity.

Don’t agree? Consider the centuries of repeatable practices, standardized tools, chemical reactions, and scientific discoveries owed to art. To the extent that there can be realities independent of the mind (the definition of objectivity), art is objective because it is process dependent.

If a ceramic artist fires a dish without first letting it dry, it will explode.

If a pianist places her fingers on the correct keys, she will play the intended chord.

If a web designer selects Dingbats for body text, large portions of his client’s site will be illegible.

The big takeaway, Miklos, is that I mostly agree with you. Art, and thereby design, is a mixed bag of objectivity and subjectivity sprinkled with enough ambiguity to keep this Art vs. Design debate raging on for years to come.

Conclusion

It is not at all clear that these words—‘What is art?’—express anything like a single question, to which competing answers are given, or whether philosophers proposing answers are even engaged in the same debate… The sheer variety of proposed definitions should give us pause. – Kendall Walton

At their most fundamental level, both art and design seek to communicate something, and whatever the differences, or whether classified as fine, commercial, or applied art—at their best, both forms elicit an emotional response.

It has been argued that the difference between fine and applied art is context and has more to do with value judgments made about the work itself than any indisputable distinction between the two disciplines. Furthermore, comparing “art” and “design” is, though a lofty endeavor, perhaps a quixotic one, as neither can be defined absolutely because they are always changing—boundaries are constantly being pushed and will hopefully continue to be so into the future. This debate, after all, is timeless.

How do we decide what is art and what is design, and why is the relationship between the two so fractured? Is it the difference between what is functional (design) and what is non-functional (art) that creates the dissension? Is a Noguchi coffee table or a Rennie Mackintosh chair merely a functional object, or is it art that happens to have a function?

Glaswegian architect, artist, and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh was one of the first proponents of integrated art-architecture. He believed in the pure integration of form and function and sought throughout his career to bring forward the theory of “the room as a work of art.”

Frank Lloyd Wright believed so strongly in the unity of form and function that he changed the oft-misunderstood axiom, “form follows function” coined by his mentor Louis Sullivan to read, “form and function are one.” His plan for the Guggenheim “…was to make the building and the paintings a beautiful symphony such as never existed in the world of Art before.”

In conclusion, it is not art versus design, but the unity of the two that is at the core of any superior design. In other words, good design incorporates art.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

Is a graphic designer an artist?

Graphic designers are first and foremost designers. Though graphic designers may incorporate art into their work, the main role of a graphic designer is to visually solve communication problems using design elements like text, images, colors, and shapes.

What is the difference between fine art and graphic design?

Graphic design relies on design methodology to solve problems and craft clear visual messages. Art is similar to graphic design in that it involves image making, but the end result may be viewed differently by different people.

What is the difference between art and design?

Design is focused on achieving solutions with measurable results, whereas art is more concerned with expressing ideas that may have more than one meaning.

What defines something as art?

Defining something as art often proves difficult, but in general, art is centered on conveying ideas, emotions, and experiences in a way that allows for multiple interpretations.

Miklos Philips

London, United Kingdom

Member since May 20, 2016

About the author

Miklos is a UX designer, product design strategist, author, and speaker with more than 18 years of experience in the design field.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT