Why Do Share Buybacks Fail? Some Suggested Remedies

Share buyback schemes, if executed poorly, can be disastrous for shareholders and company stakeholders. Using three examples from the UK market, reasons for failure are explored with some suggested remedies for managers making capital allocation decisions.

Share buyback schemes, if executed poorly, can be disastrous for shareholders and company stakeholders. Using three examples from the UK market, reasons for failure are explored with some suggested remedies for managers making capital allocation decisions.

Jamie has helped raise more than $18 billion in equity for growth, M&A, and distressed situations with clients such as France Telecom.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

In my first article, I demonstrated examples of when share buybacks had been successful for three different companies. Each respective firm had deployed the corporate action at an opportune time, such as in anticipation of operational recovery or to make positive signals to the market.

This does not imply that stock repurchases are always good decisions.

Regardless of market environment, it’s axiomatic that buying back overvalued equity destroys value. No amount of PR spin, tweetstorms, or ego can sustainably obfuscate a business that needs to be repriced. Warren Buffet makes this point very clearly in his 2012 letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway (“Value is destroyed when purchases are made above intrinsic value”). Allocating valuable capital to repurchase stock when it is not appropriate rarely ends well.

In the US, stock repurchases immediately pre-dating the Global Financial Crisis are often highlighted as case studies of value destruction. For example, Bank of America buying back USD $18 billion in stock in the two years to 2007, before its stock fell 60% in 2008 or AIG, repurchasing over USD $6 billion in stock in 2007, seeing its price plunge 96% in 2008! These case studies of hubris provide a stark warning.

Share Buyback Disasters: Case Studies of Failure

Returning to the UK equity market, it is also possible to identify a rogues’ gallery of buybacks that have failed. A sample of these firms amply illustrates the pitfalls of buying back overvalued stock.

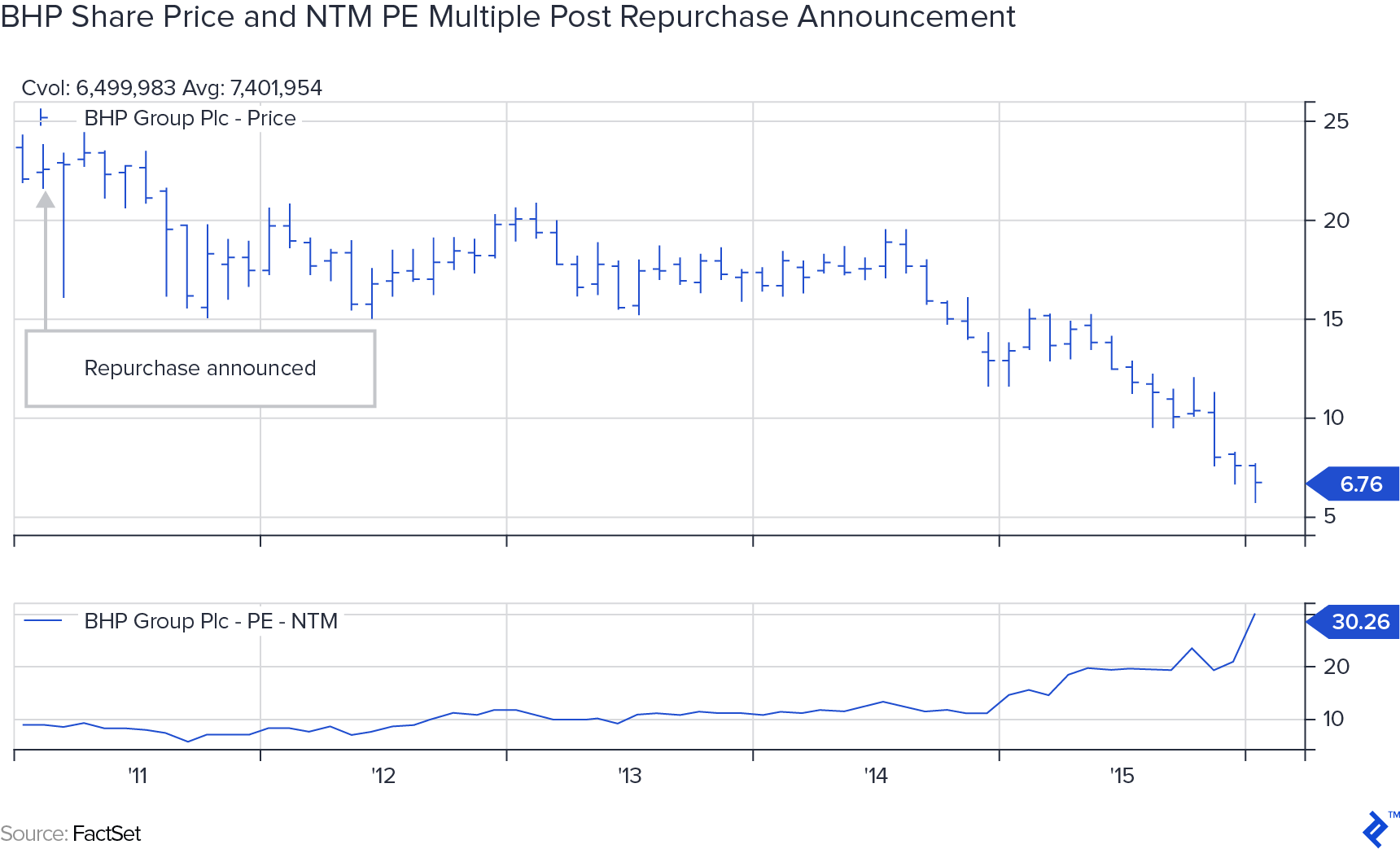

1. Cyclical Industries: BHP (Mining)

BHP is an Australian headquartered mining, metals, and petroleum business. Their experience provides a cautionary note for executive management of highly cyclical businesses. With EBITDA growing +60% year-over-year, significant operating cash flows (USD $12.2 billion) and ‘underlying’ return on capital at 41%, BHP announced a USD $10 billion capital management program with its interim results, in February 2011. This buyback program was subsequently completed six months early (end-June-11). It is reasonable to describe the initiation of this buyback program as managerial hubris.

In its results release, BHP cited “confidence in the long-term outlook” and a “commitment to maintain an appropriate capital structure.” Despite management’s confidence, subsequent share price performance was dire (see chart below). One year following the repurchase announcement, BHP’s TSR was -22%. Stretching the time horizon to four years (e.g., to February 2015), BHP’s TSR was -26%, compared to the broader UK large-cap index’s TSR of +31% over the same time period.

This case study highlights the difficulty of successfully timing stock repurchases for commodity price-sensitive business models. Despite relatively high levels of supply concentration, BHP is a price taker in the iron ore, copper, and metallurgical coal markets, which collectively account for the vast bulk of group sales. Key commodity prices for BHP fell sharply from 2011. While calling the direction of commodity prices is notoriously treacherous, given the underlying strength of the business, more counter-cyclical thinking from management would have been constructive. Perhaps BHP fell into the trap of thinking “this time is different,” underpinned by a never-ending commodity “supercycle”?

At the time of writing, BHP’s stock price is £19, still below the £23 level at the time of the 2011 repurchase announcement. Iron ore prices and copper levels are also substantially below 2011 levels. Near peer Rio Tinto suffered a similar experience following its repurchase activity in 2011. Together, their experiences provide a sobering perspective on the danger of mis-timing share repurchases.

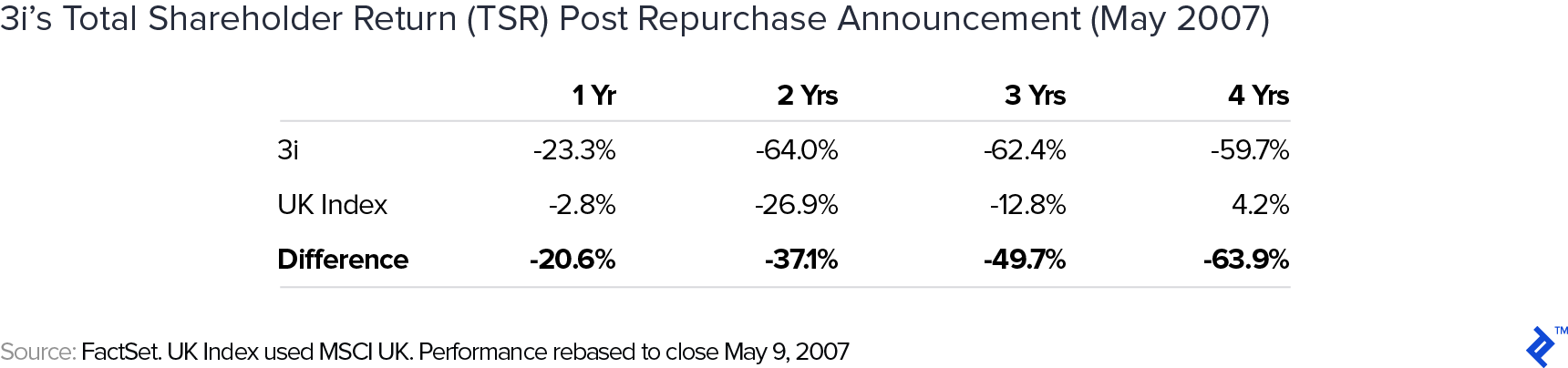

2. Massaging Metrics: 3i (Private Equity)

3i, an investment manager focused on mid-market private equity, provides an intriguing case study, even though it didn’t actually reduce its share count. Following a bumper year bringing the firm’s Balance Sheet towards a net cash position, 3i announced its intention to return cash to shareholders via a B share process in May 2007. A B share process gives shareholders in UK firms the opportunity to elect for their gain to be treated as either capital or income, depending on their tax requirements. For companies with significant retail shareholders, a B share process is generally viewed as a positive.

This was 3i’s second B share return in the space of two years. The primary motive given was the optimization of their return on equity along with maintenance of an efficient balance sheet. The decision to return this cash garnered little interest from securities analysts on the results call.

Subsequent shareholder returns for 3i proved exceptionally poor, even in the broader context of the Global Financial Crisis. In the year following the full year results announcement in May 2007, TSR for 3i was -23% vs. the large-cap UK index at -3%.

Underperformance continued. Four years down the line, 3i’s TSR was -60%, compared to the UK index up 4% (see Figure 8). While it is true that financial leverage can turbo-charge operating returns, 3i’s experience shows it can work both ways. This has proven particularly true for financial service firms.

Interestingly, 3i had to fall back on a rights issue in early 2009, as the executive board decided “a more conservative financial structure for 3i is appropriate.” The purpose of the equity offering was to reduce debt on the balance sheet. The primary winners from this cycle were advisors earning fees.

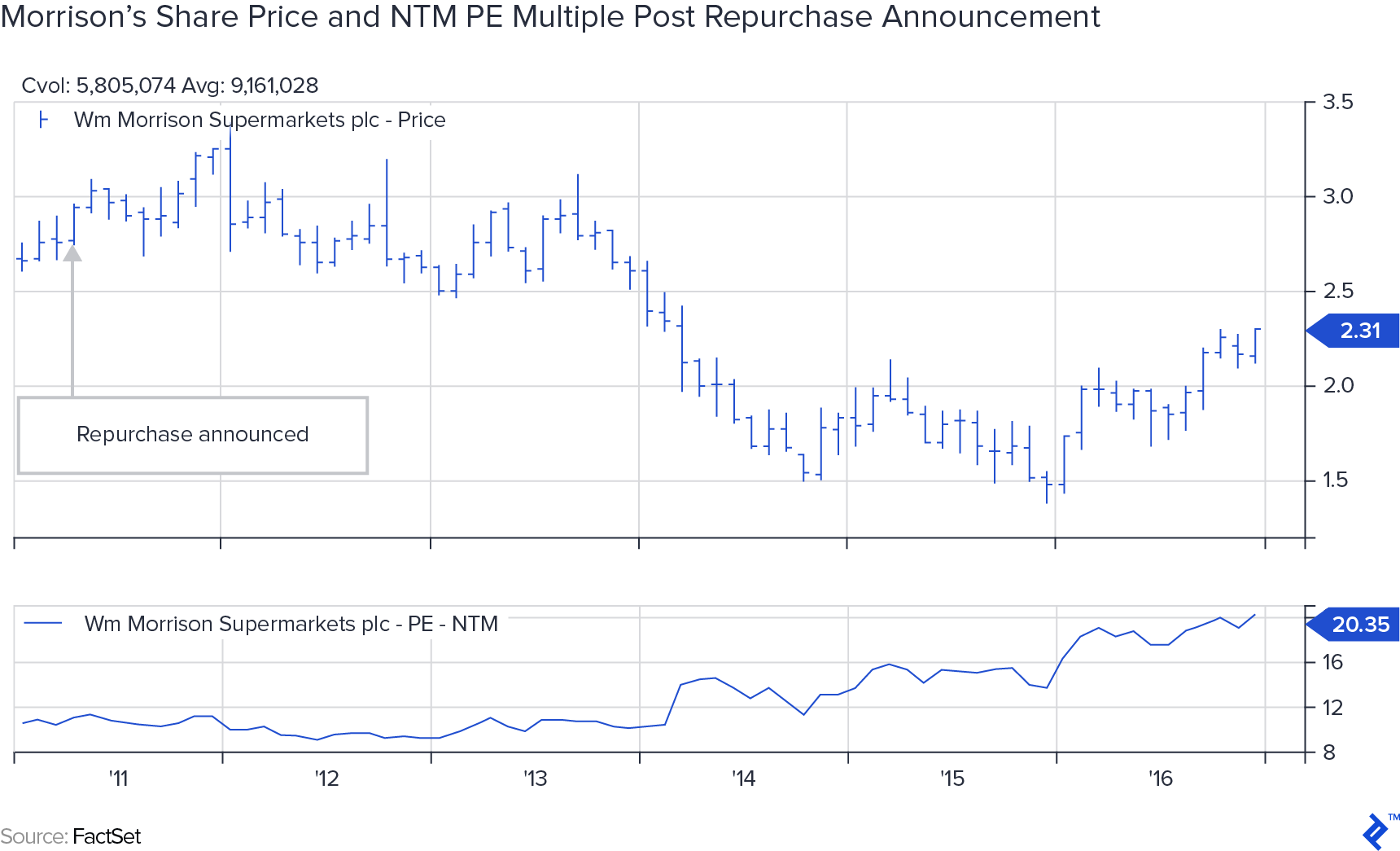

3. Contradictory Decision-making: Morrisons (Supermarket)

Destroying value through share repurchases is not isolated to bulk miners or financial service firms. The experience of Morrisons, a UK supermarket group, in the 2011/12 period is instructive. Shortly after the appointment of a new CEO, Dalton Philipps, in 2010, the firm committed to returning £1 billion through share repurchases in the two years to March of 2013. The primary motivation mentioned was to enhance shareholder returns. On this basis, the equity retirement program proved an abject disaster.

Morrison’s was operating in a weak macro environment, with low wage growth, in a market being heavily impacted by the growth of discounters, such as Aldi and Lidl. Additionally, Morrison’s lacked any meaningful capability in local (convenience formats) or online. These two areas remain some of the highest structural growth areas of the UK retail market.

In his outlook statement, Phillips forecast “a challenging year in 2012.” The annual report further notes “a very tough economic climate.” It is unusual to see this kind of language in official company communication when initiating special returns. Despite these structural and cyclical disadvantages, management elected to return cash. In hindsight, this appears extraordinary.

In 2011 and 2012, Morrison returned >£0.3 billion and >£0.5 billion, respectively, in share buyback form, equivalent to approximately 4% and 7% of its average market value in each year. TSR from these levels proved dreadful. Four years after the initial announcement of the repurchase program, Morrison’s TSR was -21% compared to a UK market TSR of +37% over the same time period.

Morrison’s share price has never recovered to the near £3 levels it traded at prior to the buyback program (see below). Today, it still languishes near £2.4 per share. The CEO responsible for these errors was ousted in early 2015. His experience offers a sobering perspective on misallocating capital.

Financial Engineering Does Not Work

One of the prime reasons share buybacks have got a bad name is the dubious practice of managing share count dilution. Many, many publicly listed firms engage in modest buyback programs to reduce stock option exercise dilution and manage reported earnings per share (EPS). High technology firms, most often listed in the US, have been particularly guilty.

This type of engineering in isolation rarely (if ever) works. McKinsey has shown that while there is a relationship between total returns to shareholders (TSR) and EPS growth, there is no correlation between share repurchase intensity and TSR. Unsurprisingly for seasoned investors, fundamentals (organic sales growth, margins, returns on capital, etc.) are more important. Arguably, it would be far better to increase low paid workers’ remuneration and/or fund moon-shot style investments than engage in financial engineering. This is a vital area for more rigorous debate by all stakeholders.

Common Problems with Disclosure Regarding Share Buyback Policies

Perhaps the most striking feature of this study is the lack of detail that management teams have provided historically when announcing plans to buy back stock. Ambiguity is not unusual and is rarely (if ever) challenged by securities analysts on conference calls, post results.

Opacity has been a key theme across repurchase announcements. Vague reference to financial discipline and future confidence are common. What is clear is that the track record of firms solely aiming to manage their capital structure through a buyback process has often been underwhelming.

Capital Structure Management

We have considered the experience of BHP, Rio Tinto, and 3i in detail. According to their public statements, all three firms were aiming to manage their capital structure via a share repurchase program. For example, BHP sited “confidence in the long-term outlook” and “commitment to maintain an appropriate capital structure.” At their results call, BHP CEO Marius Kloppers went further, stating “BHP continues to be very well positioned to deliver value to our shareholders…We believe we are well positioned to continue to outperform.” He could not have been more wrong. Each program destroyed substantial equity value. The experience of Evraz, buying back due to reduced leverage and improved liquidity, provides a contrary example. This apparent contradiction presents an intriguing puzzle.

This trend has been further underpinned by the growing use of rolling repurchase programs by firms. Under these arrangements, all surplus capital, as defined by the individual corporate, is automatically returned to shareholders via a buyback. The timing and execution are outsourced to a third party to avoid a conflict of interest. Management justifies their approach by noting how difficult it is to identify and exploit the top and bottom of market cycles in advance. This is a cop-out. By definition, permanent rolling repurchase programs do not account for periods of overvaluation. While calling overall market cycles is highly challenging, insiders spotting dislocations in specific sectors where they have worked for over 30 years is not. This is rarely acknowledged and should provide food for thought for every board and other stakeholders.

Clear Language and Messaging Is Vital

Often, the rationale that has been advanced has been dubious. While British American Tobacco (BAT) created substantial value from buying back stock at the turn of the decade, the explanation provided suggested surplus capital (failure to conduce M&A) and financial engineering (boosting reported EPS) as the key motives. With the benefit of hindsight, this was unhelpful. In reality, BAT management clearly had a private view that regulatory risk was manageable and pricing power could offset volume challenges. That is why they were so keen to buy assets (engage in M&A). Over time, this view was proven spectacularly right. Arguably, BAT management could have been more explicit in public.

There have been exceptions to this trend. When initiating their successful repurchase program, Next clearly stated “shareholder value can be enhanced by returning surplus capital to shareholders.” At the time, the Next chairman noted the excellent position of the balance sheet (albeit it was still a net debt position) and expectation for strong positive cash flows.

Management also made it crystal clear that organic investment in the core business remained the most attractive option for capital allocation, and repurchases would not in any way impair this. This candor deserves credit. Ahead of their time, Next management was addressing concerns that buybacks reduce real investment. Other management teams can still learn from this approach.

Nevertheless, mixed messages were also evident. There is more than a hint of financial engineering in the fact that Next was only prepared to buy back stock in the open market when such action resulted in an increase in earnings per share. In their annual report, Next management observes they “decided to embark on a program to enhance EPS through share buybacks.” As discussed, this motivation lacks any meaningful empirical justification. This has not stopped successive generations of UK executive management teams using it as a reference point. Examples outside the UK are common.

Unfortunately, explicitness from executive management does not guarantee success. For example, when initiating their buyback, Rolls Royce stated, “The aim of the buyback is to reduce the issued share capital of the Company, helping enhance returns for shareholders.” This proved wildly optimistic. The review of Morrison’s also demonstrated the primary motivation was enhancing shareholder returns. Yet, the repurchase decision destroyed significant value for remaining shareholders.

A Framework for More Robust Capital Allocation

So what can we learn from the experience of these UK listed firms during the past 20 years? Is it possible to develop a more robust framework to help boards and other stakeholders improve their approach to capital allocation? The answer is firmly YES!

1. On an Overall Basis, Buybacks Do Work

This review supports the thesis that on average, firms that buy back substantial stock create value. Due to their flexibility (vs. dividends) and relative tax efficiency (capital gain vs. income), buybacks remain an important tool for future capital allocation. There, announcements can contain valuable information. All that said, it is vital to ring-fence announcements that are “in the noise” from more meaningful repurchase activity. Too many buybacks appear token in nature, designed to manage share count and boost reported EPS. This is not an optimal use of capital and should be challenged.

2. Beware of Hubris

The cure for high prices is high prices. This is particularly true for price taking and highly cyclical business models. Returning a substantial amount of cash as a special return several years into what appears to be a super-cycle is likely a bad idea. The experience of 3i, BHP, and Rio Tinto provide a strong proof statement. Spending time with management would have risked Stockholm syndrome.

On the other hand, the cure for low prices is low prices. The decision by Evraz to aggressively repurchase stock amid a cyclical low in steel was well rewarded. While no management team can expect to buy at the absolute bottom, their inside knowledge of the industry, past cycles, capacity utilization, customer demand, marginal cost, and marginal pricing underpinned their information advantage vs. other public market participants. This is a valuable lesson.

3. Hubris, Coupled with Management Change, Is a Red Warning Light

Special care should be exercised by new management when taking on a new firm or new industry. This review identified the hubris shown by Morrisons in repurchasing stock. While an experienced grocer, the new CEO had limited experience in the UK market. Phillip’s had spent much of his career working in Germany, Brazil, and Canada. With hindsight, his decision to aggressively return cash to shareholders, rather than transform Morrison’s position in the local and online markets, proved costly.

A similar lesson is evident at Rolls Royce. Incoming CEO Warren East had developed his reputation in the semiconductor industry, primarily with ARM Holdings. His decision to continue with the buyback program initiated by his immediate predecessor has been shown to be a mistake. This again provides an important lesson for board members, employees, pensioners, regulators, and investors.

4. Clear Goals Need to be Mandatory

Stakeholders in all their shapes and sizes would be better able to evaluate the success (or failure) of repurchase programs if boards were more explicit articulating their goals when initiating share buybacks. For management themselves, improved transparency at the outset would allow those managers with the best track record for allocating capital greater flexibility and freedom for future decisions. This also applies to activist shareholders pushing target firms to initiate repurchases to spur improved performance. Arguably, the market environment is already changing. For example, at the time of writing, Masayoshi Son, the founder and Chairman of Japanese conglomerate Softbank, has announced a new buyback explicitly aimed at closing a perceived valuation gap. Criticism of repurchase activity continues to build on social forums such as Twitter.

Always Take Care of Every Stakeholder

References to enhancing EPS helps fuel the fire of populists. Managing share dilution from employee compensation is not a valid reason for buying back stock. Recognition of this risk demands careful scrutiny of planned repurchase activity by all stakeholders, particularly if funded by debt (what Hyman Minsky categorized as Ponzi finance).

It may seem trite, but bears repetition; board members need to be careful in balancing the needs of all stakeholders. Capital and operating investment in the business that exceeds the cost of capital will always be the optimal path forward. Alongside economic profit, full-time headcount, wage growth, tax contribution, and impact on local communities are also important key performance indicators. It is vital that boards do not give the impression that share buybacks are at the expense of these aims. While not perfect, the approach taken by Next offers a good starting framework.

Understanding the basics

What does a buyback mean for shareholders?

Share buybacks return capital to investors and lower the amount of outstanding capital.

Are share buybacks a good thing?

Share buybacks are a tax-efficient way of returning capital to investors and also signals that stock might be undervalued.

What happens to share price after buyback?

A share price will tend to rise after a share buyback due to the supply/demand dynamic of there being less shares in circulation.

Jamie Mariani

Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Member since October 29, 2018

About the author

Jamie has helped raise more than $18 billion in equity for growth, M&A, and distressed situations with clients such as France Telecom.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT