Share Buyback Addiction: Case Studies of Success

Share buybacks have become a popular financial tool for cash-rich businesses that are running short on sufficient projects to invest in. Three case studies are presented here that demonstrate when share buyback schemes are successes.

Share buybacks have become a popular financial tool for cash-rich businesses that are running short on sufficient projects to invest in. Three case studies are presented here that demonstrate when share buyback schemes are successes.

Jamie has helped raise more than $18 billion in equity for growth, M&A, and distressed situations with clients such as France Telecom.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Share repurchases are very much an on-trend topic in financial markets, with 2019 on course toward setting a record for the number of public shares being bought back by their issuers. This is a topic that I have covered throughout my career in equity research and, through this article, I’m looking to bust common myths about share repurchases within the corporate world.

This briefing—split into two parts—addresses the efficacy and effectiveness of share repurchase activity in the UK public equity market during the past 20 years. This first article looks at the positive aspects of buybacks and why they are so popular, with examples of how they have been deployed successfully, while my follow-up piece will analyze the contrasting instances of when they have failed. Wherein I will present an alternative, more robust framework for future capital allocation decisions.

Is There an Addiction to the Share Buyback?

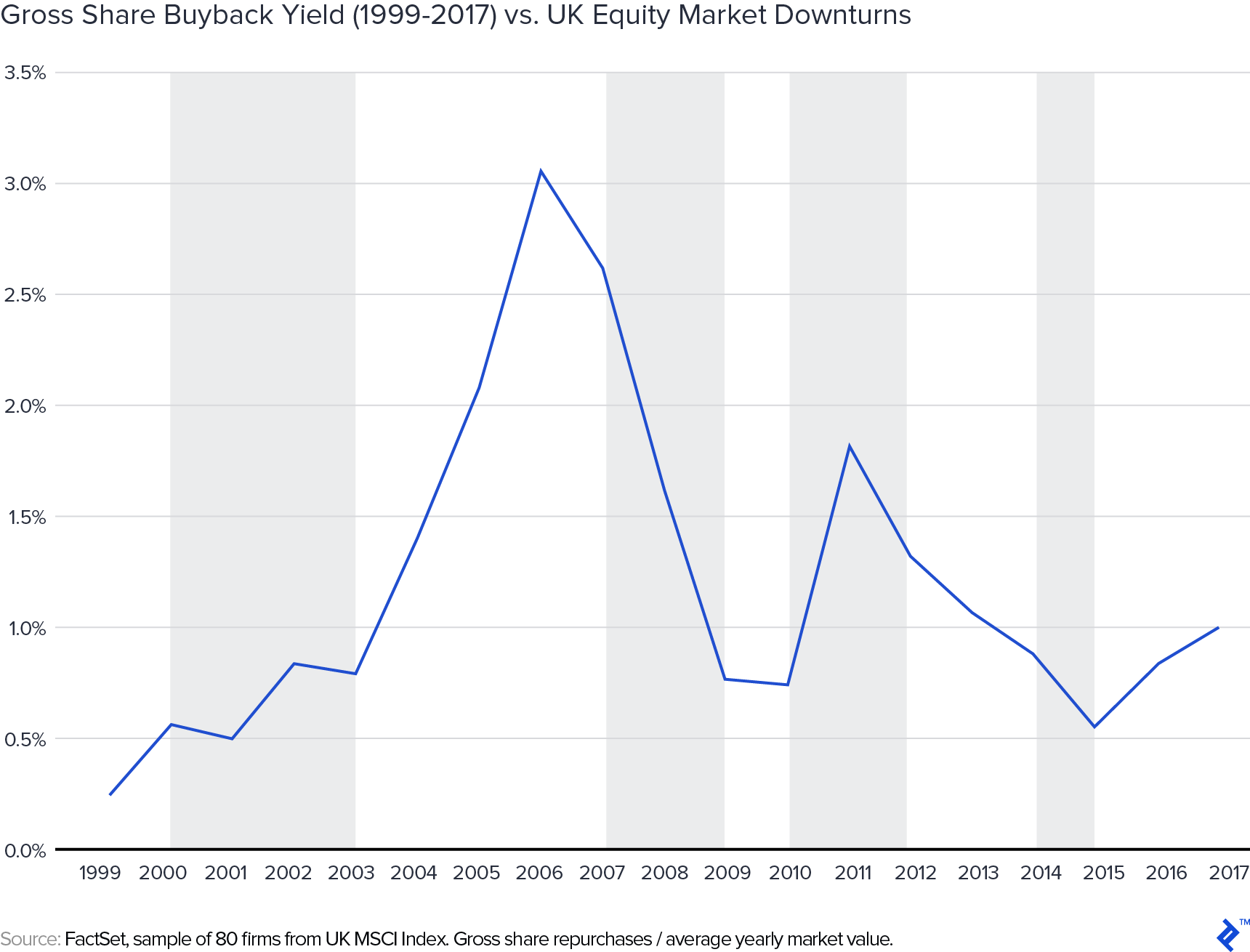

Publicly listed firms have become increasingly addicted to share buybacks. The chart below shows gross buybacks as a percentage of market value for a representative sample of UK firms. Over time, there is a clear growth trend, notwithstanding market downturns (grey shaded areas).

A similar pattern is evident in other countries, most notably the US. A key question is why?

The rationale for share repurchases is well rehearsed. Academics have argued that buybacks provide:

- A tax-efficient means of returning excess capital to shareholders, and

- Due to information asymmetry, a signal that the firm is undervalued.

Leading management consultants, such as McKinsey, agree: “A buyback’s impact on share price comes from […] the signals a buyback sends.” This is frequently echoed by the talking heads on financial TV stations such as CNBC, activist investors, and executive management teams looking to spur improved performance from out-of-favor firms. Who can forget Carl Icahn cajoling Tim Cook to increase the size of Apple’s stock repurchase program via Twitter?

Had a nice conversation with Tim Cook today. Discussed my opinion that a larger buyback should be done now. We plan to speak again shortly.

— Carl Icahn (@Carl_C_Icahn) August 13, 2013

The Devil’s Advocate View

A growing band of commentators have turned against this received wisdom. They observe shareholders looking to harness capital gains instead of income taxes, who could always just sell their shares in the open market anyway. They are rarely reliant on repurchases. They note share repurchase activity has often been pro-cyclical. Executive management has shown minimal appetite to buy back stock at the cyclical trough. Share repurchases of overvalued equity near the top of the cycle destroys value.

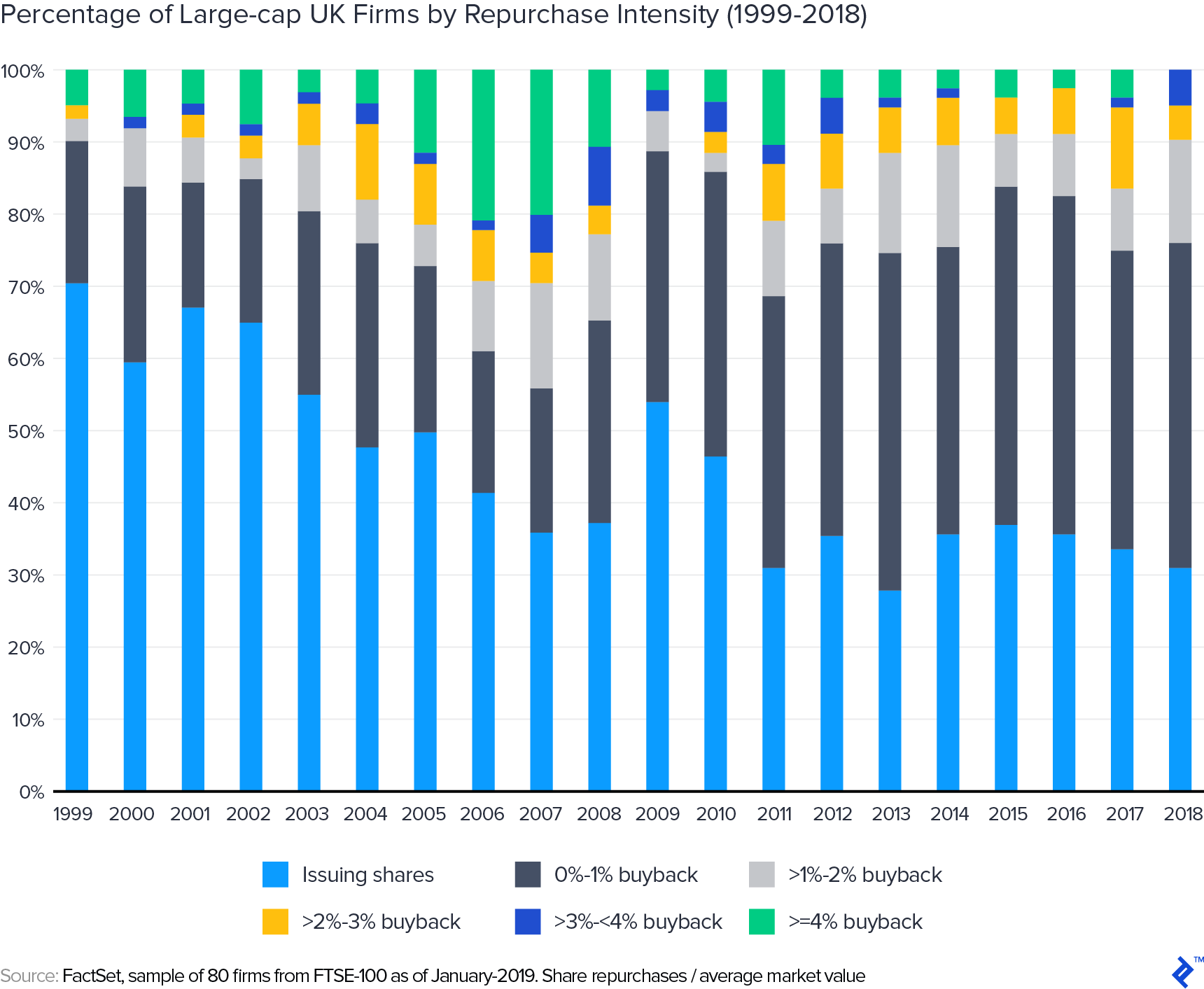

The signaling value of permanent, rolling repurchase programs has also been questioned. Using this devil’s advocate lens, the primary motive for repurchases is seen as financial engineering (boosting reported EPS, a metric often tied to remuneration), in the hope of creating sustainable value. It is a fact that most firms only buy back a small proportion of their stock (see above chart). Looking back 20 years, on average my analysis shows that nearly 80% of UK firms dilute shareholders or buy back less than 2% of their market value in any given year. Less than 5% of firms pursue aggressive repurchases.

Politicians, such as Bernie Sanders in the US, have developed this theme. While the evidence remains disputed, they accuse US listed firms of underinvesting and squeezing their employees’ wages and post-retirement benefits to fund buyback programs. Copycat accusations elsewhere could follow.

What can we learn from past repurchase activity? Does financial engineering work? Can executive committees and employees reconcile these apparently diametrically opposing views? Or will the rise of populism end the current practice of share repurchases?

Share Buybacks Do Work: Case Studies of Excellence

Looking back over the past twenty years, there has been significant share repurchase activity that has added value. UK data, covering the collapse of the TMT bubble, the financial crisis, and subsequent recovery, provides a proof statement. When reviewing the data, it is important to distinguish between firms based on:

- The size of the gross repurchase (relative to market value). From a market practitioner’s perspective, the repurchase of 1-2% of the share count in any year is in the noise. As a rule of thumb, repurchasing >=4% of the market value in a year represents significant activity.

- Time horizon. Solely observing price reactions over, say, 30 days, or even a year, is too short-term. 3-5 years is a more reasonable basis to assess the impact of capital allocation decisions. Analysis should focus on both absolute and relative returns over this time period.

My proprietary analysis performed on firms buying back >=4% of market value on average indicates:

- Positive absolute returns on a one-, two-, three-, and four-year time horizon

- Positive relative returns vs. the UK large cap index over the same time horizons

The weight of evidence is clear. Similar trends are observable in the US. Interestingly, the number of UK firms delivering outperformance increases substantially as the time horizon stretches. Intuitively, this makes sense, and suggests that substantial repurchase activity continues to provide signaling value to stakeholders outside of the executive management team.

1. Undervalued Stock: British American Tobacco (Consumer Goods)

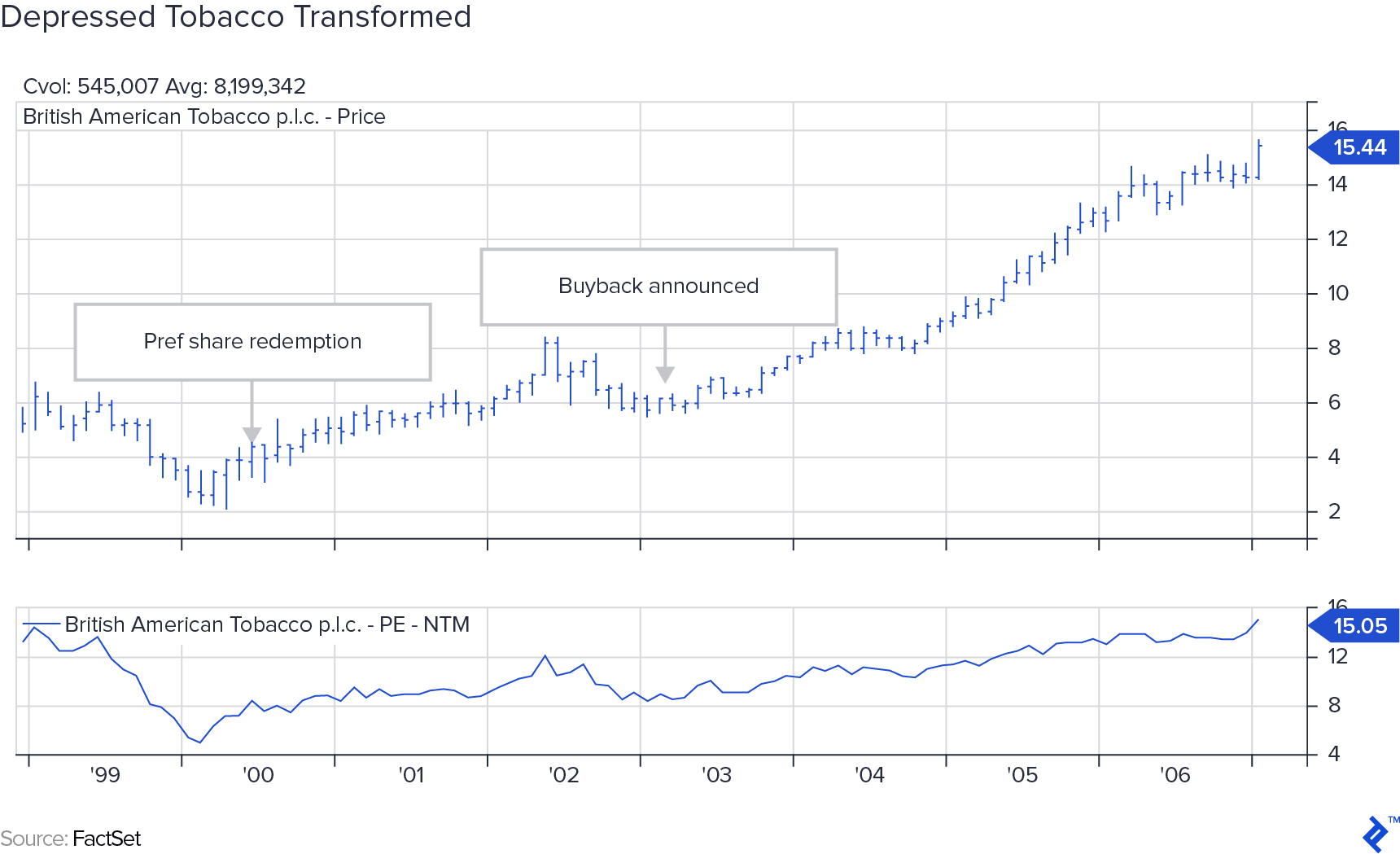

BAT has long been a poster child for share repurchases. At the turn of the century, tobacco stocks were deeply depressed, reflecting widespread negative sentiment regarding litigation risk from negative health outcomes. Relative valuation multiples were at trough levels, with BAT trading at around 5x NTM PE (see below chart), offering a dividend yield close to 7%.

Beyond executive management, few believed these firms could successfully manage the regulatory risk and overcome declining volumes. For example, BAT’s equity had posted a negative return of nearly 30% in 1999 as investors flocked to dotcom business models.

In early 1999, BAT agreed to acquire peer Rothmans International from Richemont, providing improved scale, political influence, and opportunity for cost savings. Given the divergence in views between investors (Mr. Market) and management, M&A was a rational first choice for capital.

The deal was financed by shares. This transaction resulted in preference share redemptions of £695 million (around $1.0 billion) in 2000 (approximately 8% of average market cap in the year) at £5.75 (approximately $8.60) per share, a decision that richly rewarded remaining BAT shareholders. Total shareholder returns (TSR) in the year following the redemption were +50%, compared to the large cap UK index falling 4%. Over two, three, and four years, massive out performance accrued to BAT shareholders. For example in June of 2004, four years after the redemption, BAT TSR was 142%, versus the UK index at -18% for the same period.

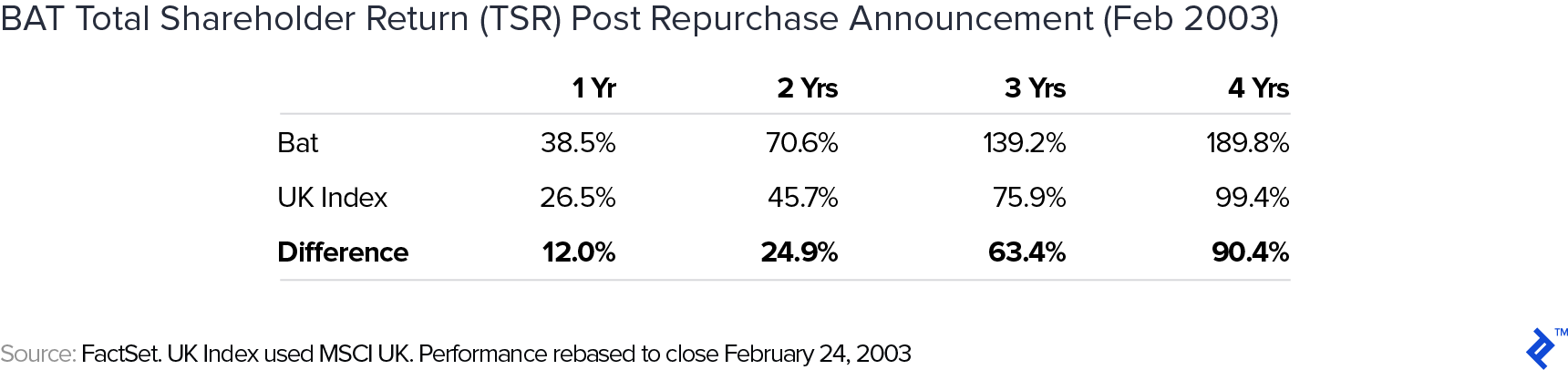

Not content, in early 2003, BAT initiated a further aggressive ordinary share repurchase program, buying back nearly £700 million (around $1.1 billion) of stock, corresponding to approximately 5% of its market value (on a daily average market capitalisation basis). TSR continued to be impressive, which you can see in the table below.

BAT’s 2002 results call transcript provides insight into this decision. On the 2002 call, Martin Broughton, Chairman and CEO of the group, emphasized that repurchasing shares was the board’s least preferred route for capital allocation. Further M&A was clearly the board’s desire. However, given the strength of BAT’s balance sheet (around 5-9x gross interest coverage ratio being a reasonable range according to the executive team) and apparent inability to conclude a deal, the board felt compelled to initiate a share repurchase. With hindsight, it is easy to spot powerful signals being conveyed.

In the 2003 annual report, Broughton cited improving EPS as a key motive, perhaps indicating more luck than judgment on the part of the executive management team in timing the repurchase decision. That said, it should come as no surprise that TSR was a key driver of long-term executive compensation plans at the firm. Buying back cheap publicly traded shares versus their intrinsic value was a smart decision by the executive team that rewarded shareholders.

This is important. ESG investing as an asset class has grown substantially in recent years. ESG-led investors often negatively screen out investment in the tobacco sector as well as other harmful business models, noting concerns around “sustainability.” BAT’s experience reminds us that sentiment can become too negative on these types of business models. Sustainability can prove much more durable than feared. Put another way, investors willing to back these firms at points of significant pessimism can make outsized returns. Executives and investors in today’s market can learn from this case study. In simple terms, buying back undervalued stock works.

2. Signaling Properties: Next (Retail)

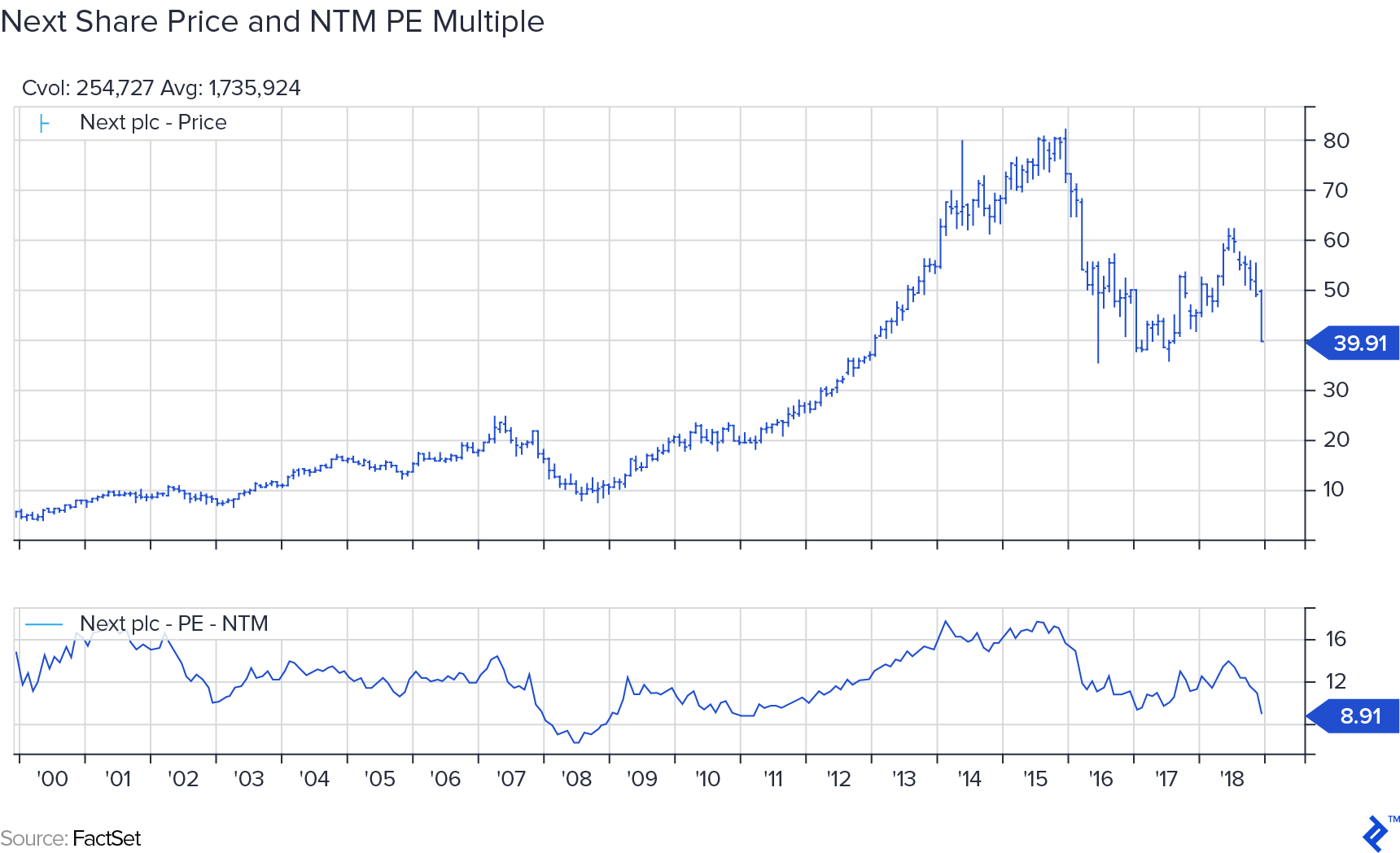

The apparel retailer Next, in the crosshairs of the notoriously challenging UK high street, also stands out. This is a firm that has regularly conducted share repurchases on an opportunistic basis.

As the TMT bubble developed in 1999, brick-and-mortar retailers like Next were deeply out of favor, with eCommerce platforms expected to steal their customer base. With year-end results to January 29, 2000, Next reacted, announcing a substantial share repurchase plan. In the annual report, the Next chairman noted the excellent position of the balance sheet (albeit it was still a net debt position) and an expectation for strong positive future cash flows. As such, Next believed that “shareholder value can be enhanced by returning surplus capital to shareholders.”

During the remaining calendar year, Next purchased nearly 8% of its average market value. Subsequent returns to shareholders were impressive. TSR in 2000 was +39%, with significant positive returns accumulating over the next three years, which the chart below shows.

Not content with its initial repurchase plan, Next repeated the trick on an ongoing basis, buying back >4% of its average market value in many years to come, with 2002, 2003, 2006, and 2007 being particularly significant in size. Returns from these purchases have also been impressive.

Next’s policy of only buying back shares when it is in the interest of their shareholders has been successful. Unlike many other firms engaging in repurchases, Next has always emphasized the primary importance of investment in the business and clearly stated their aim in buying back stock. Put another way, the buyback process for Next has contained valuable signaling information.

3. Predicting Recovery: Evraz (Steel & Mining)

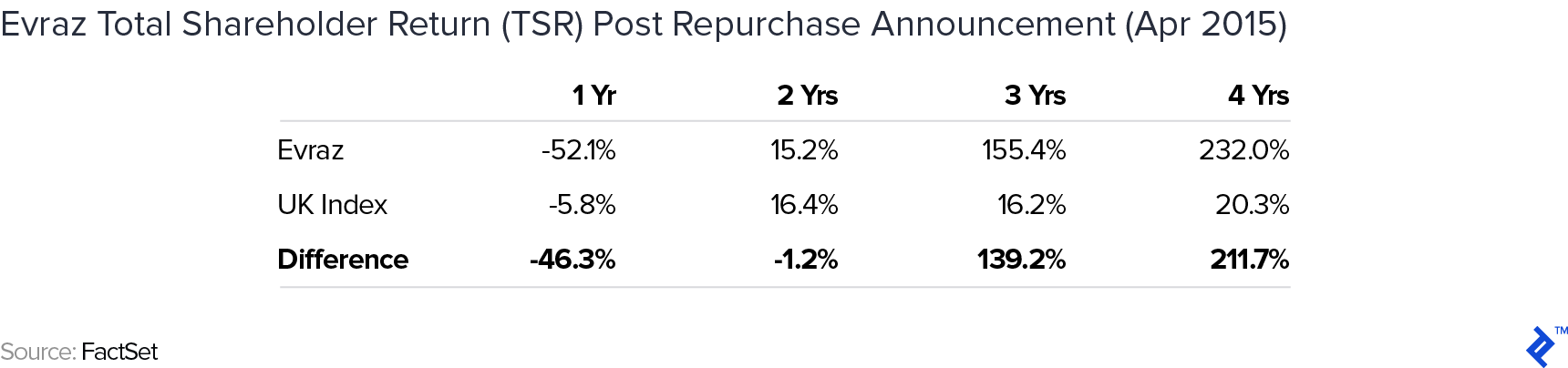

The UK listed Russian steel and mining firm controlled by Roman Abramovich also provides an interesting case study for buying back stock. With 2014 annual results, Evraz announced a return of capital to shareholders “in light of strong financial performance” with a limit (around 8% per shareholder). Minimal further rationale was offered. On the Q4 call following results, the Evraz CFO noted reduced leverage and improved liquidity as providing surplus capital, with a buyback the preferred option for returns. The repurchase occurred in April 2015.

The firm’s share price performance around the announcement of special returns remains fascinating. From spring 2014, steel prices experienced a sell-off. This accelerated precipitously from the end of 2014 into early 2015. According to Evraz management, global steel prices fell approximately 28% in 2015 underpinned by structural overcapacity and weak demand. Global capacity utilization fell to around 65% at the end of 2015, the lowest level since the bottom of the Global Financial Crisis.

In other words, the buyback was announced despite operating conditions deteriorating as steel prices fell. The initial results from the repurchase announcement appeared disastrous. While the repurchase was ongoing, the Evraz share price declined from an undisturbed price of £1.88 per share (31/03/2015) to £0.73 at 31/12/2015. While management was unable to pick the absolute bottom in their equity valuation, subsequent equity price recovery from the beginning of 2016 has proven extraordinary. Taking a four-year view from the date of the announcement, TSR came in at +232% vs. the UK index at only +20% for the same time period.

This is a business model with significant operating leverage. Add on financial leverage and Russian country risk, it is not surprising that Evraz’s equity value behaved in a volatile fashion. That said, we can clearly see the signaling value of the repurchase decision. In calling out capacity utilization levels in particular, management made a strong call for recovery, supporting the old adage “the cure for low prices is low prices.” This case study stands in marked contrast to BHP and Rio Tinto’s experience, which I will be exploring in my next article.

Repurchases from Melrose Industries (2011, 2014, and 2016), an industrial conglomerate; Land Securities, a REIT (1999 and 2002); Schroders, an asset manager (2006 and 2008); and Astra Zeneca (2011-12), a healthcare firm managing around a patent cliff also provide positive case studies.

These highly successful share repurchases can help inform and critique capital management priorities today. Similar case studies are available for the US and other markets.

Don’t Confuse Genius with a Bull Market

Notwithstanding these case studies, in a rising equity market, it should come as no surprise that repurchasing stock generally results in positive returns. Given that the past twenty years have witnessed two significant bull markets (and the end of a third into the TMT bubble), it is reasonable to question the representativeness of the sample. A new, protracted bear market could provide new insights.

In light of this, in my next article, I will explore the alternative view of share buybacks and show when they haven’t worked. Similar to this article, I will show some examples of companies that deployed them suboptimally, followed by some of my suggestions on how capital allocation decisions can be handled better by organizations.

Understanding the basics

What does a buyback mean for shareholders?

Share buybacks return capital to investors and lower the amount of outstanding capital.

Are share buybacks a good thing?

Share buybacks are a tax-efficient way of returning capital to investors and also signals that stock might be undervalued.

What happens to share price after buyback?

A share price will tend to rise after a share buyback due to the supply/demand dynamic of there being less shares in circulation.

Jamie Mariani

Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Member since October 29, 2018

About the author

Jamie has helped raise more than $18 billion in equity for growth, M&A, and distressed situations with clients such as France Telecom.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT