Green for Takeoff: Inside the Electric Airplane Industry

Will electric airplanes dramatically reduce fuel costs, save the environment, and jumpstart the dying regional industry? In this article, we examine why electric airplanes are having their moment in the sun. We size the market, take bets on the winning players, investigate the challenges in current technologies, and take a guess at when you’ll be flying in an electric plane.

Will electric airplanes dramatically reduce fuel costs, save the environment, and jumpstart the dying regional industry? In this article, we examine why electric airplanes are having their moment in the sun. We size the market, take bets on the winning players, investigate the challenges in current technologies, and take a guess at when you’ll be flying in an electric plane.

Elizabeth was an equity research analyst on both the buyside and sellside before transitioning to freelancing where she specializes in market research and valuation.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Why United Reduced Its In-flight Magazine by One Ounce

In 2018, United Airlines began printing its inflight magazine on lighter paper, cutting 1 ounce from each magazine to 6.85 ounces. At the time, United operated 744 mainline aircraft with an average seat capacity of ~210. This translates to a reduction of just ~13 pounds per flight—about the same weight as a scrawny Cavalier King Charles. Yet, United said this generated 170,000 gallons of fuel savings annually, translating to $290,000 in fuel costs.

Airline industry profit margins are some of the thinnest of any industry in the world. And fuel is nearly half of the cost to run an airline. Therefore, it is no surprise that airlines are constantly seeking new and creative ways to lower this “uncontrollable” and large expense.

Enter: the electric airplane.

The electric airplane promises to reduce fuel costs significantly (just how much is still up for debate) while simultaneously saving the planet (somewhat) from hazardous fuel waste. Yet, if Tesla is any indicator, the road from fossil-fuel to electric is not a smoothly paved one; battery, infrastructure, safety, and regulatory issues abound.

This article analyzes the reasons why the electric airplane is coming to the forefront now, the technologies and hurdles, the size of the market, and the competitive landscape. We’ll also take a guess at when you’ll be flying in your first electric plane.

Why Are Electric Airplanes Taking Off Now?

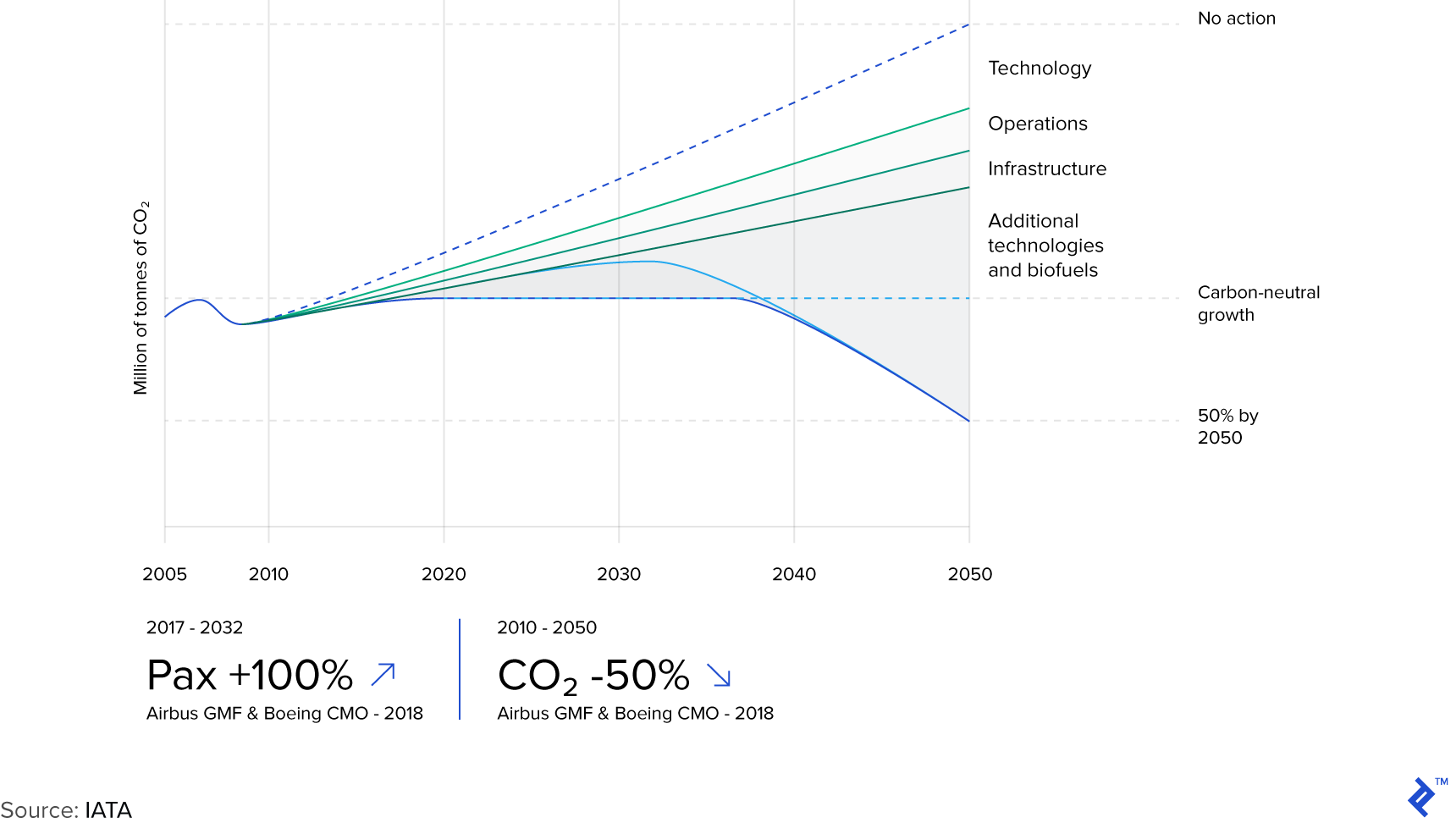

The primary answer to the question of why electric airplanes are having their moment in the sun now is climate regulation. Recently, US and foreign regulators have made serious calls to reduce emissions. While “only” 2-3% of worldwide emissions come from flying, according to Roland Berger, this could reach 10% by 2050 or even 24% if other sectors get cleaner faster as some experts are predicting. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a United Nations agency, is calling for a cap on net aviation CO2 emissions as of 2020 (carbon-neutral growth). With greater adoption of electric propulsion, this could remain relatively steady at 2-5%.

Air Travel Growth and Emissions Forecasts From IATA

And, of course, there is the economic element. The business case for electric aircraft essentially rests upon 3 pillars:

- Lower operating costs

- Unleashing a new regional travel market

- Ability to meet mandatory carbon emissions standards

According to electric plane startup Ampaire, an electric aircraft vs. fossil fuel aircraft can have a 90% reduction in fuel costs, 50% cut in maintenance, 66% quieter takeoff & landings, and 0% tailpipe emissions. These reduced costs will be a boon to the $26 billion short-haul market (~30% of all flights currently)—creating service between small, regional airports that are currently uneconomical.

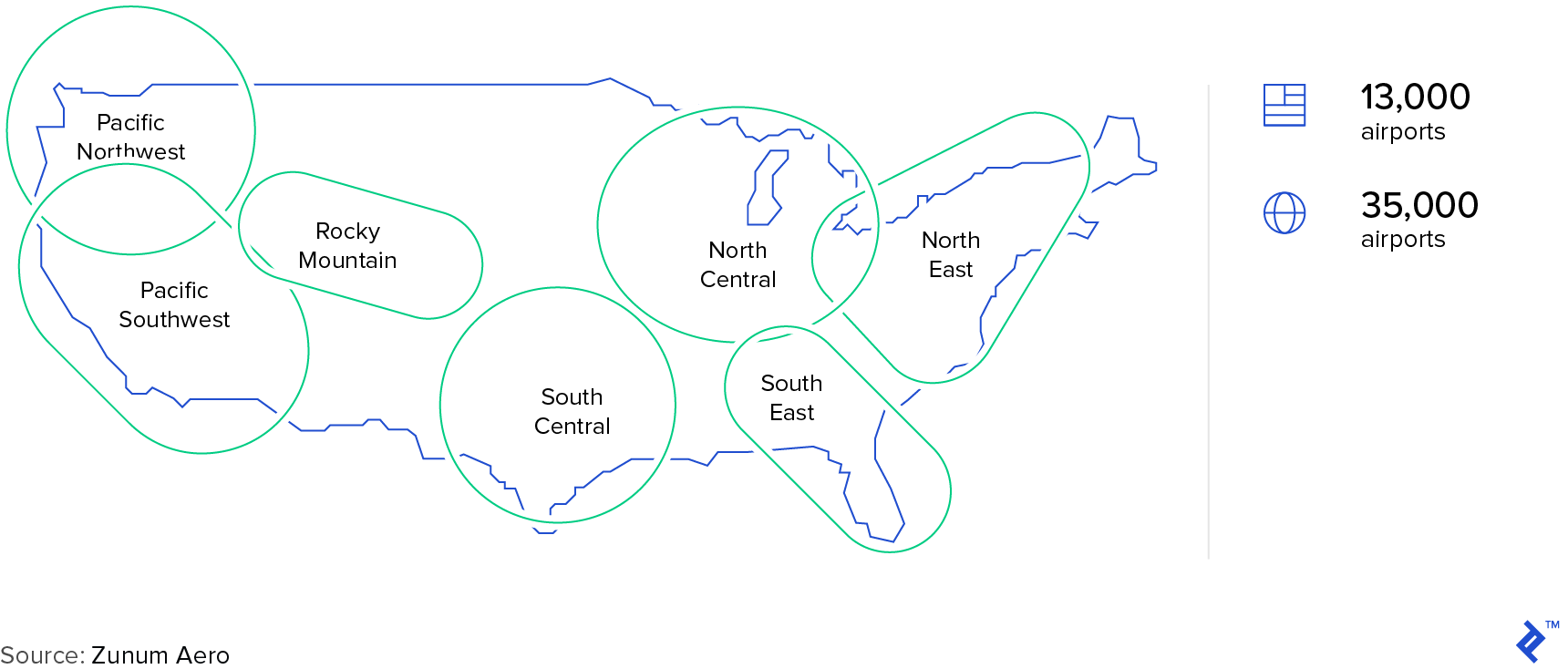

Dean Donovan, managing director at aviation-and-travel investment firm DiamondStream Partners, sees how electric planes can save the day for currently uneconomical regional destinations, estimating an additional ~8,000 airports would be able to be served profitably.

Electric Planes Expected to Open Up Previously Unprofitable Regional Routes

Additionally, thanks to many of the technological breakthroughs from automotive companies working on electric vehicles, new lower-cost, lighter-weight, and high-power solutions are coming to market.

However, while all of the factors mentioned have been building slowly over the past few years—nothing is exactly new. What really brought things to a tipping point, according to Wright Electric CEO Jeffrey Engler, is Tier 1 suppliers and supporting players announcing their commitments to electric airplanes. “For example, last year, Heathrow Airport announced that they’re going to waive landing fees for the first year, for the first hybrid electric planes or electric planes. The year before that, easyJet announced that they were working with us. By itself it’s just one piece, but if you add it up, it’s meaningful.”

Actual skin is now in the game.

In April 2019, Collins Aerospace unveiled plans to develop the electric flight market, including a high-power, high-voltage $50 million facility for designing and testing the “industry’s most power dense and efficient propulsion motor” in Rockford, Illinois. In June 2019, Rolls-Royce accelerated its electrification strategy by acquiring Siemens’ electric and hybrid-electric aerospace propulsion business. Finally, the latest announcement in July 2019 came from BAE Systems which announced they will be working with electric airframer start-up Wright Electric on “flight controls and energy management systems.”

An Enormous Regional Market Waiting to Ignite (Market Size Analysis)

The electric aircraft market is tiny currently—an estimated $99 million in 2018. MarketsandMarkets forecasts this to grow to a modest ~$122 million by 2023, a CAGR of ~4%. For comparison’s sake, the electric vehicle market is around $119 billion and the global commercial aircraft market is $840 billion. So the potatoes are currently small. To be blunt, there are just no electric-powered aircraft in commercial operation today.

Looking further out, the future looks…well, electric. UBS forecasts a $178 billion hybrid electric aviation market by 2040 with particularly strong growth starting in 2028 when the first hybrid electric 50-70 seater aircraft is expected to be delivered. This assumes about 16,077 deliveries with an average price of about $11 million. Market appeal is expected to remain limited until 2028 with a lack of competitive products, however, as new, scrappy entrants like Eviation, Ampaire, and Wright Electric come out with viable products, the market should begin to take flight.

The regional market, defined as trips ranging less than 500 kilometers (km) or ~310 miles are expected to lead growth for electric and hybrid planes. This is due to (1) limited battery capacity and (2) new economic viability of serving these previously money-losing routes.

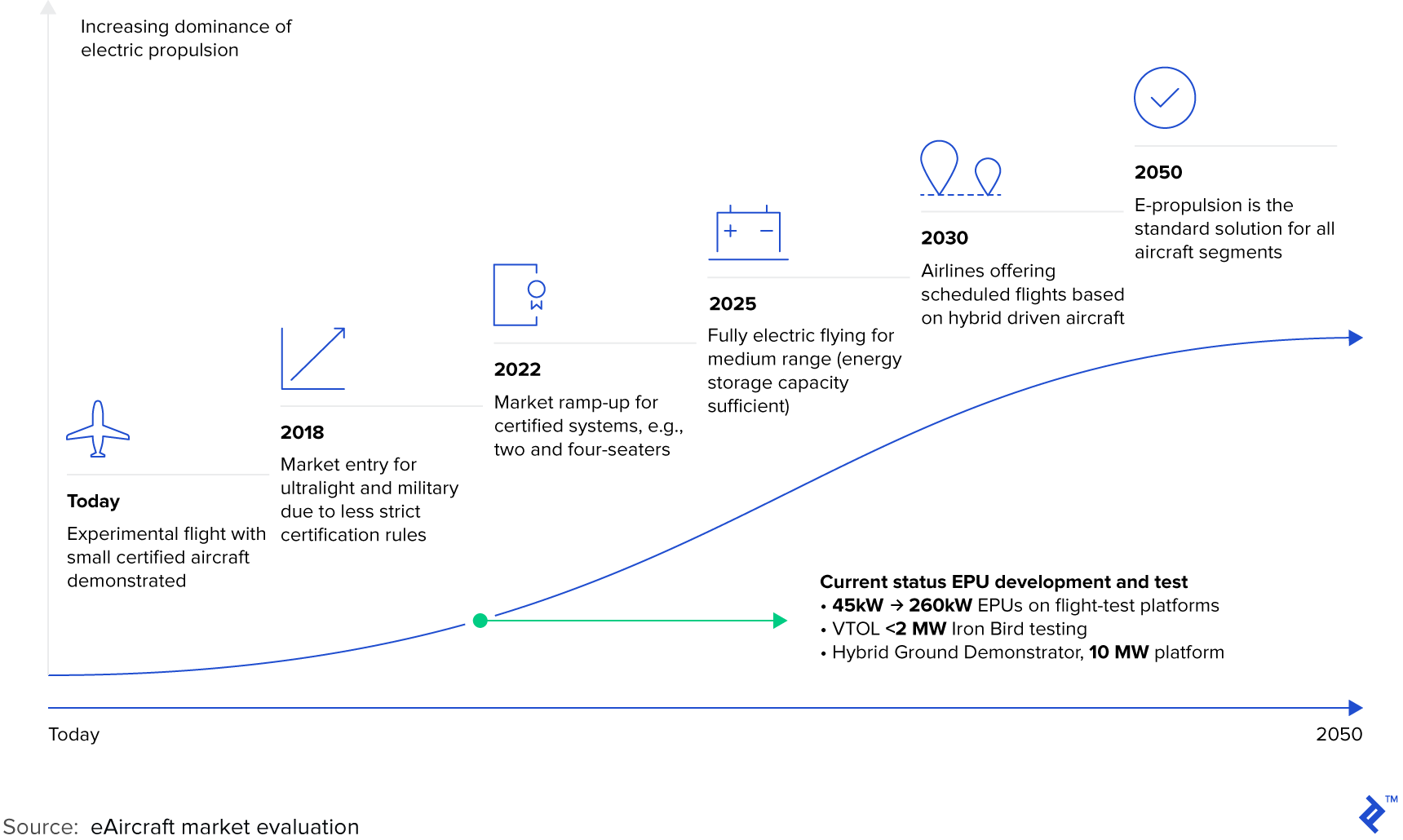

Siemens forecasts a relatively similar chronology with the expectation of ultra-lights and military aircraft landing first (due to less strict certification rules), followed by a ramp-up for certified systems in 2022, scheduled flights based on hybrid aircraft in 2030 and then finally, by 2050, Siemens predicts that electric propulsion will be the “standard solution” for all aircraft segments. Roland Berger’s panel of aerospace experts’ prediction is in a similar hemisphere—forecasting the first >50 seat hybrid electric aircraft will enter commercial service by 2032.

Siemens’ Electric Propulsion Prediction Map: E-propulsion will be the Standard by 2050

Let’s look at the market from a utilization perspective. CEO of Ampaire Kevin Noertker estimates, “Major carriers serve ~150 airports in the United States. Commercial US airlines service about 500 airports, however, there are about 5,000 municipal airports that could support commercial aviation. This means the amount of airports that could be served commercial could increase 10x.”

Another way to think about it is to look at the expected number of regional aircraft that will be retiring and therefore need to be replaced. The major OEMs predict around 10,000 9-passenger aircraft will need to be replaced assuming zero market expansion. Assuming an aircraft price of $5-10 million, this sizes the market at $50-$100 billion. However, many in the industry, including Noertker, expect a significant expansion in the regional market “driven by reduced prices on existing routes, but especially driven by opening up new routes that have never really been profitable before.” Noertker goes on to note, “The most conservative groups are saying double the number of aircraft needed. Some are going so far as to say 10x increase in the number of aircraft servicing the market. The increased demand being the driving factor.”

Next, let’s take a look at the individual players driving this market.

Big OEMs Dipping Their Wings Into Electric

Big OEMs like Boeing and Airbus have dipped their toes into the electric plane market. Boeing partnered with startup Zunum (more in Shocking Startups below) to help give itself some exposure to the industry and Airbus has experimented with projects like Vahana, City Airbus and E Fan X.

In addition to its investment in Zunum, Boeing’s Aurora Flight Sciences, an aviation and aeronautics research company acquired in 2017, is working on developing a network of flying taxis with an Uber partnership. In January 2019, Aurora Flight Sciences conducted its first test flight of its all-electric autonomous passenger air vehicle (pictured below).

The test was relatively small, however, as the vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft hovered just for a few seconds before landing. It is progress to see, however, that a big OEM like Boeing is investing in the future of autonomous, electric “flying taxis,” creating an entirely new mode of transportation for urban mobility (think: skyscraper hopping).

Airbus is also interested in launching its own flying taxi network. Last year, Airbus demonstrated its Vahana VTOL aircraft. In March 2019, Airbus and Audi presented its 4-passenger air taxi CityAirbus as part of the EU initiative Urban Air Mobility project and tweeted “maiden flight soon.”

However, there are so many uncertainties—eventual economics, regulatory issues, safety issues, infrastructure issues (how does an already struggling air traffic control system deal with a 10x increase in the number of 9-seater planes?), and more. These unknowns make it hard for big, publicly-traded OEMs to invest significant capital and therefore open the market up to entrepreneurial, spirited start-ups looking for alpha.

Dean Donovan, managing director at aviation-and-travel investment firm DiamondStream Partners, notes, “OEMs are very interested in the space, but see the value from working with start-ups to complement their existing skills. They recognize the strengths of their existing models in many cases complement rather than compete directly with the start-up ideas. It isn’t obvious on how it will play out, so start-ups let them participate in some areas in a low risk way.”

So let’s take a look at these scrappy, new players.

Shocking Start-ups Electrify a Sleepy Industry (Financial Model & Competitive Landscape Analysis)

Roland Berger estimates that there are about 170 electric aviation concepts underway currently. However, despite significant customer demand, few of the 170 deals that have received funding were funded at scale, according to Dean Donovan. Donovan makes the point that if each of those 170 companies required ~$100 million in funding, the overall industry would need $17 billion in funding - a relatively large amount of capital compared to its sector size.

The reason, Donovan argues, why this cash is so tough to come by at the institutional investor level is because the investing profile of an aircraft start-up is much harder to stomach versus the current field of opportunity which is primarily focused on software. Software startups can get to a minimum viable product quite easily. However, certification issues for aerospace startups drive enormous upfront costs. Meanwhile, the company generates zero revenue. This means the pitch to a VC firm is that you have a very cool product that the government might let you sell eventually. In the meantime, the company likely needs to spend $2 million per month.

So how do we bridge this funding gap? Based on past experience, you need the heart and soul of a billionaire willing to invest in a pet passion project. A la Paul Graham and the Stratolaunch (an aircraft built to carry rockets to space) or the more obvious one, Elon Musk and electric cars and space travel. If that’s the answer, then it looks like Eviation has the biggest leg up at this point with its backing from billionaire Richard Chandler. But let’s take a look at all the players more in-depth.

Ampaire - Eyes on the Prize: Aggressively Focused on Regional

Strategy

Los Angeles-based startup Ampaire is focusing on six-, nine-, and 19- passenger aircraft initially. Ampaire is using an existing structure and retrofitting a solution—praised by the IDTechEx report as a “walking before they try to run strategy.” Ampaire CEO Kevin Noertker believes “the most capital-efficient approach and time-efficient approach is starting with existing airframes.”

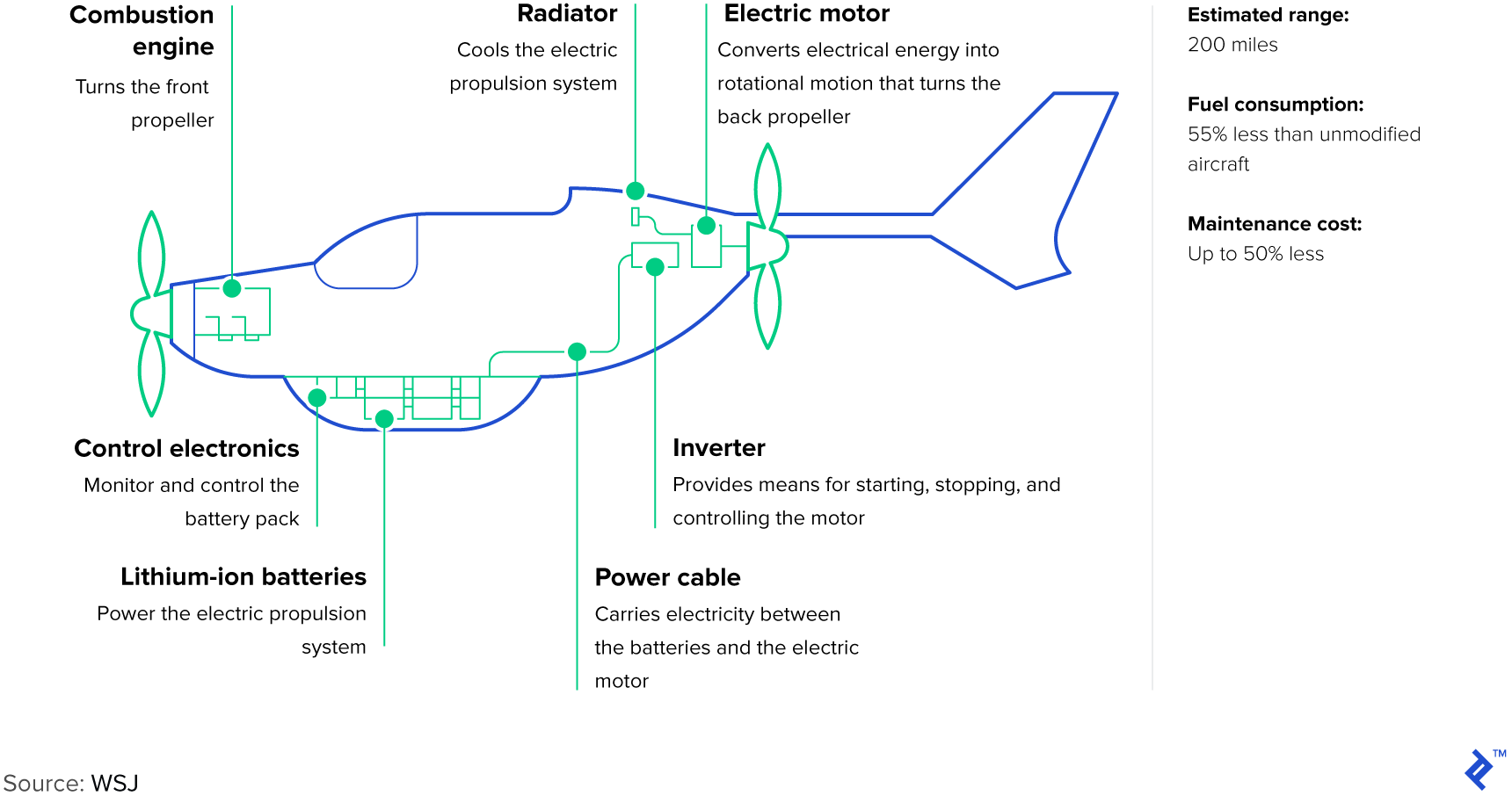

Ampaire recently successfully tested a five-passenger aircraft with a retrofitted electric motor powering a propeller in the back of the plane with a normal combustion engine driving the propeller at the front of the plane. The retrofit, originally a Cessna Skymaster, can travel up to 200 miles on a single charge and uses 55% less fuel than an unmodified plane and costs up to 50% less to maintain. Ampaire CEO Kevin Noertker says, “It’s kind of like a plug-in hybrid car. We are really riding the coattails of ground electric vehicles here.”

Customers

Beginning later this year, Hawaii’s Mokulele Airlines will begin testing a hybrid aircraft with Ampaire on its commuter route between Kahului and Hana airports in Hawaii. The current plan, according to Noertker, is to have the hybrid service commercially available by 2021.

Beyond Mokulele, Ampaire has 14 letters of interest (LOIs) from regional airlines. To Noertker, these are the most important customers he can win.

[Regional airlines] are the companies that know the ins and outs. They struggled to be profitable due to the cost of fuel. They need planes now. And so that's where we're focused.

Kevin Noertker, CEO of Ampaire

Funding

Ampaire has raised money from a variety of VCs, government grants, and from players within the aviation industry such as engine manufacturer Continental Aerospace.

Wright Electric - Blitzscaling to 150-seater Planes

Strategy

Wright Electric is another Los Angeles-based startup attacking the electric plane market. Wright’s business plan is to become an airframer, similar to Airbus and Boeing, whereby they design and integrate systems. However, to begin with, Wright is taking a common 9-passenger existing plane and doing a retrofit. Unlike Ampaire, Wright’s ultimate goal, however, is to go after the more traditional passenger aircraft—a 150-seater plane.

Customers

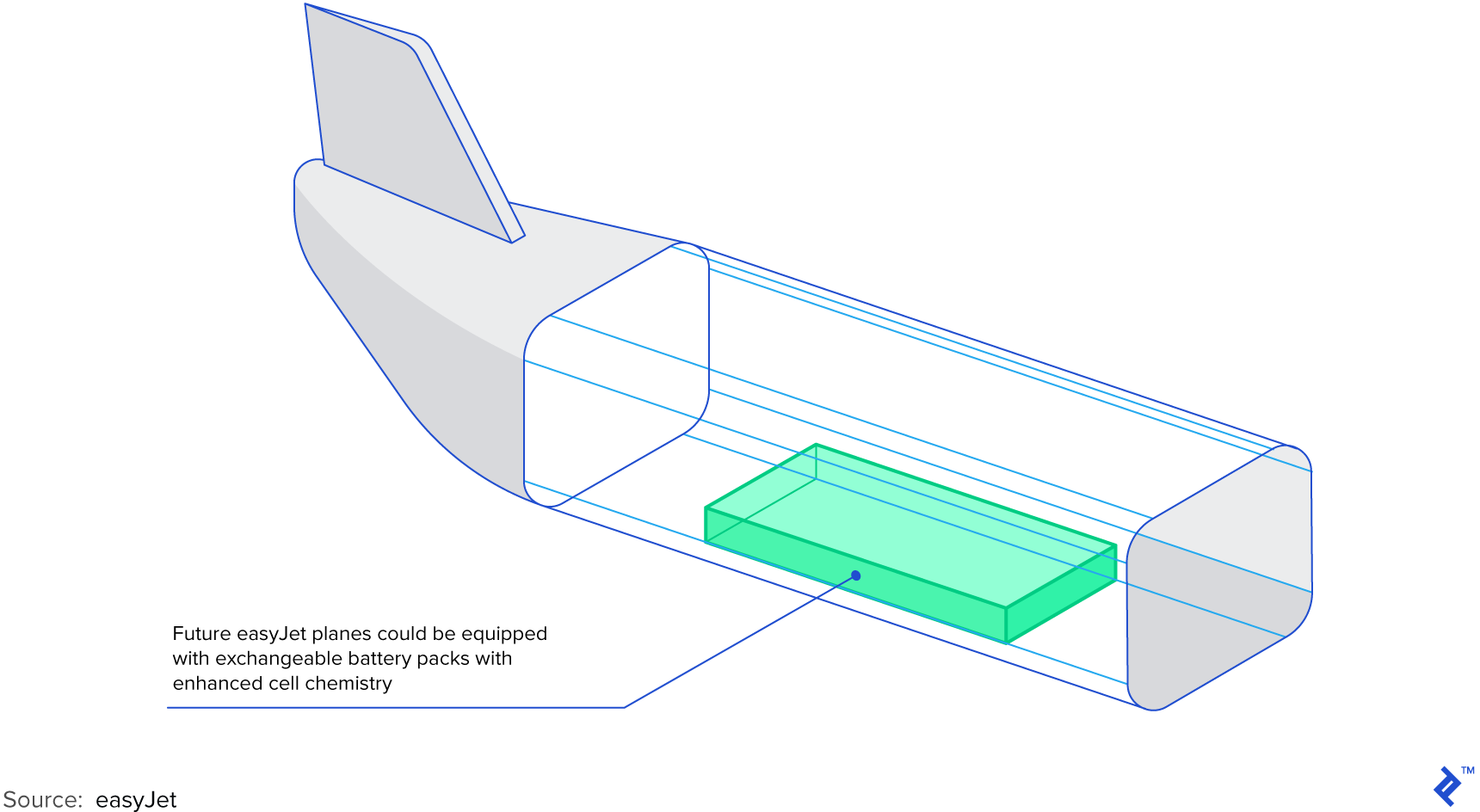

In 2017, Wright Electric and easyJet partnered together to build a 180-seat electric aircraft to fly routes of up to 300 miles beginning in 2027. easyJet makes a natural partner for Wright Electric as the low-cost airline has a long history of promoting the innovation of low emission aircraft and, of course, reducing expenses. However, creating a fully electric jet of such a size does seem like quite a stretch—and likely won’t happen for at least a decade.

Future easyJet planes could be equipped with exchangeable battery packs with enhanced cell chemistry.

Funding

In 2017, Wright Electric debuted its idea for a no gas 150-seat aircraft at the Y Combinator Demo Day in Silicon Valley with the goal of short-haul flights in the next 10 to 20 years. According to Crunchbase, the company has raised a total of $120k with Y Combinator as its lead investor.

Zunum Aero - Enormous Vision but Sputtering Out of Funding

In Washington state, Zunum Aero, backed by Boeing and JetBlue, was preparing test flights for its hybrid plane sometime in 2019, however, recently admitted it is having a bit of difficulty raising a new round of financing. Zunum appears to have made the mistake of going straight to larger hybrid-electric airplanes. Forbes reported in July 2019 that Zunum had shuttered its Bothell, Washington headquarters, closed offices in Indianapolis and Illinois, and laid off nearly all 70 employees. The Seattle Times reported that Zunum “has run out of cash, and much of the operation has collapsed.” On its website, Zunum is currently soliciting investors for a $50 million Series B. Zunum estimates that additional equity of $80 million net of customer deposits and production loans will be necessary to bring its ZA10 to market (this includes a 150 unit/year production facility).

While some in the field believe Zunum bit off more than they could chew by trying to do propulsion and airframe at the same time, Dean Donovan, managing director at aviation-and-travel investment firm DiamondStream Partners, doesn’t see much of a difference in terms of capital required, “If you need $100 million and four years to get to flying or $75 million and three years to get to flying…does it really make a difference?” Donovan was actually impressed by the Zunum team, noting that they had “incredible vision.”

If Boeing- and Jet Blue-backed Zunum is struggling to keep its funding, how can a startup with uncertain economics and myriad technological and regulatory hurdles succeed? Perhaps the answer lies behind having one humongous billionaire backer—as is the case with the Israel-based Eviation.

Eviation - The Belle of the Paris Air Show Captures Real Orders

Eviation made quite a splash at the Paris Air Show in June. The company took “double digit” orders for its $4 million electric plane, Alice. Alice can fly up to 650 miles at ~500 miles per hour with an electric motor on its tail and each of its wingtips. Regional airline Cape Air is reported to be one of the first airlines to place orders for commercial electric airplanes.

As of February 2019 (which is, arguably, light years ago in this fast-moving industry), Eviation was a 35-employee company with ~$200 million in funding secured to get through certification—a relatively solid war chest. Most of the funding has stemmed from billionaire Richard Chandler’s private investment fund Clermont Group. Clermont invested $76 million in exchange for notes convertible to a 70% stake in Eviation according to an SEC filing.

Electric Commercial Airplane Adoption: A Touch of Turbulence to Get to Blue Skies

Fully electric aircraft use batteries (or some energy storage device like fuel cells) to power an electric motor instead of jet fuel to power an engine. Modern battery types for powering electric motors are often lithium-based, however, given the limited endurance between charges, they have limited range.

Current lithium-ion batteries would only be able to generate a maximum speed of ~200 mph versus a current passenger aircraft cruising speed of ~500 mph. While the automotive industry has made great progress on lithium-ion batteries, the auto industry would likely be satisfied with a gravimetric density of ~350-400 Wh/kg whereas current aircraft propulsion systems would need closer to ~500 Wh/kg. Therefore, it is going to be up to the aviation industry to take up the baton from here, and Roland Berger has proposed a reasonable roadmap to 500 Wh/kg batteries.

The second option, and the one most likely to take off in the near term, is the hybrid electric model which combines a gas turbine with an energy storage system that drives an electric motor during certain portions of the flight. After all, fully electric automobiles were preceded by hybrids for about 20 years.

Ampaire has retrofitted Cessnas for its hybrid concept with its Ampaire 337 wherein one of the two engines is replaced by an electric motor. Beyond the technological constraints, retrofitting hybrid models is an appealing avenue to electric plane stakeholders as regulatory oversight is likely to be less stringent.

Hybrid Electric Plane

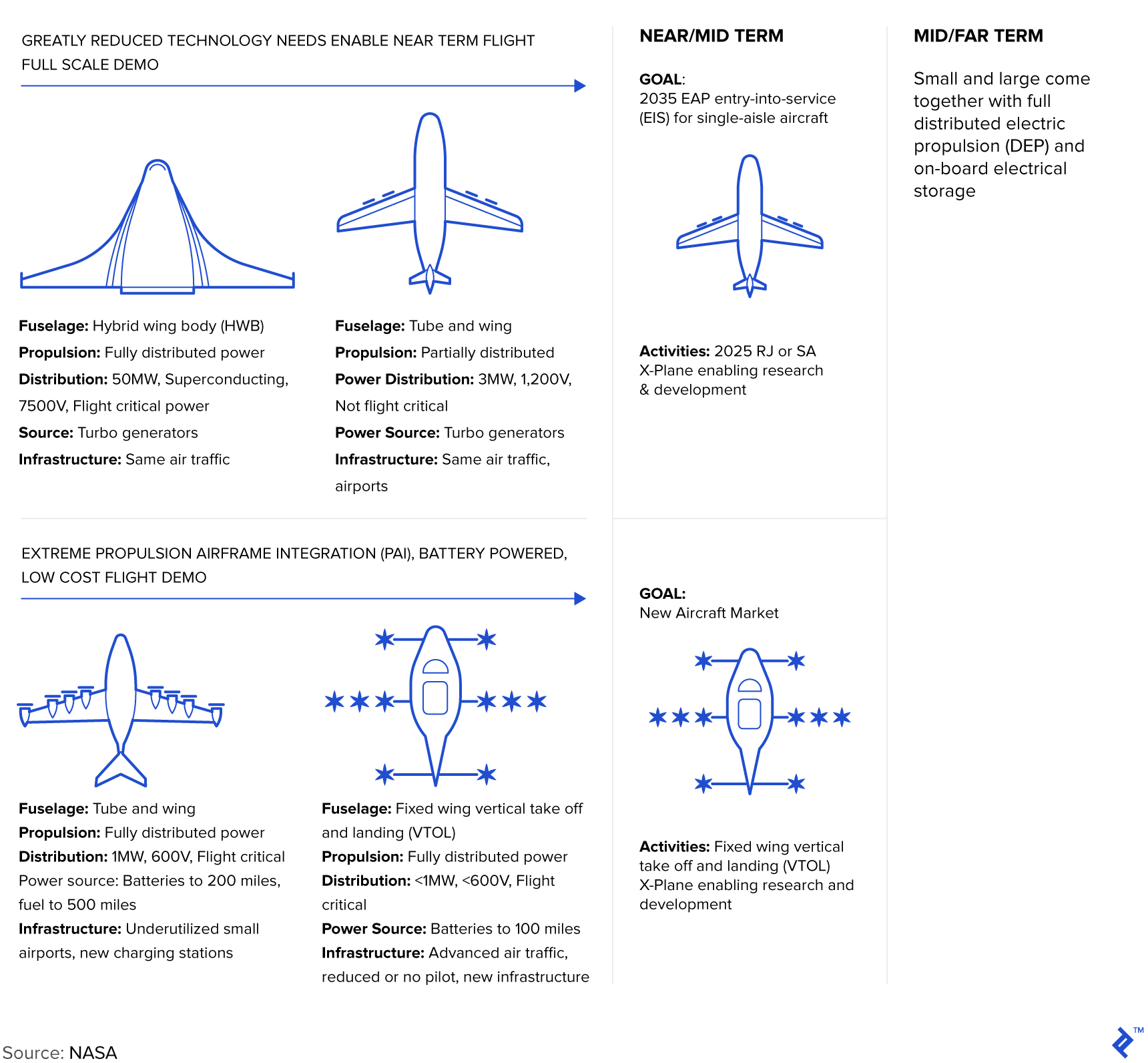

NASA was one of the first to investigate electric aircraft propulsion (EAP) in an effort to reduce emissions and noise pollution. NASA has a semi-electric aircraft whereby fuel cells rather than batteries generate electric power which it expects could be introduced into service in 2035. Essentially, they are developing power systems that are much lighter and more efficient which are expected to enable EAP for single-aisle aircraft like a Boeing 737. However, an aircraft as large as a 737 is likely very far out as initial solutions will focus on regional aircraft more suitable to serve Tier 2 airports.

NASA’s Electrified Aircraft Propulsion (EAP) Plan for Larger Aircraft

Ampaire CEO Kevin Noertker noted an interesting challenge with chasing this technology—by the time the pieces of an electrified propulsion system have gone through an FAA approval process, it will be outdated. As such, they need to continually be thinking 10 steps ahead. Noertker equates the innovation necessary to an iPhone upgrade cycle. “We have to look at regular upgrades, almost like iPhone releases to these airplanes and whether that’s in the software, the control systems or the battery technology, that’s an interesting area where you never wait. We’re not waiting for technology. We’re certainly moving with what’s available, but we have to be resilient to those changes. And that’s an interesting opportunity and challenge.”

Dean Donovan also notes some significant hurdles to electric commercial airplane adoption, “You need to solve for battery charging time, air traffic control problems, pilot issues, and safety. From a safety perspective, each individual flight could actually be safer because you can build redundancy into an electric engine that is not available in traditional engines, so if you lose a part, you don’t lose the whole thing… But with many more aircraft flying as 9-passenger planes take an increasing number of passengers, the number of accidents could increase.”

The biggest barrier to adoption, according to some of the executives we talked to, is indifference. Without getting airplane executives to believe that this is a worthwhile investment, the industry won’t take off. Wright Electric CEO Jeff Engler believes higher R&D investment from the top will trickle down to speed up many electric plane challenges. “Imagine if 100x the number of engineers were working [on the battery issue], how much more innovation we’d get.”

So When Are We Lighting Up the Skies?

The increased desire to lower emissions, lower costs, and open up a regional market are all driving factors of the hybrid electric market. It appears likely that the market addresses the following markets chronologically: (1) crop dusting/island hopping/skydiving/bush hopping small aircraft in ~2020, (2) small charter and cargo in ~2025, and (3) 50-70 seaters by ~2030.

All we need now is the battery technology (and the infrastructure). Paging Mr. Musk.

Understanding the basics

How far can an electric plane fly?

As of 2019, electric airplanes can travel about ~300 miles.

What percentage of emissions is air travel?

While only 2-3% of worldwide emissions come from flying today, this could reach 10% by 2050 or even 24% if other sectors get cleaner faster.

Elizabeth J. Howell Hanano, CFA

Annapolis, MD, United States

Member since August 21, 2017

About the author

Elizabeth was an equity research analyst on both the buyside and sellside before transitioning to freelancing where she specializes in market research and valuation.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT