Lyft vs. Uber: Hailing a Ride to Public Markets

With both expected to go public in 2019, we look at Lyft vs Uber and how they would be valued on the public markets. This analysis also comprises an overview of their respective business models, finances, and expansion strategies.

With both expected to go public in 2019, we look at Lyft vs Uber and how they would be valued on the public markets. This analysis also comprises an overview of their respective business models, finances, and expansion strategies.

Zach is a modelling, fundamental analysis and valuation expert that has managed money for PE and hedge funds. He now runs his own business.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

In recent years, ride-hailing platforms have become ubiquitous and likely now make up the most visible sector of the gig economy. People in most cities looking to go from point A to point B decreasingly walk out to the sidewalk and put their hand in the air for a taxi, but rather, summon a car with a few keystrokes on a smartphone. With voice recognition technology and self-driving cars on the horizon, there is the dream that one day people will soon be able to speak into their phone (or other connected devices) to summon a driverless car to pick them up. All of which seemed outlandishly futuristic when Batman would do so only a few decades ago.

Conventional taxi cabs are becoming obsolete so quickly that most people in US cities will give a questioning look if anyone says that they are going to get one. Once-prized New York City taxi medallions have plummeted in price from $1.3 million in 2013 to as low as $160,000. For the most part, people do not even say that they are going to get a Lyft or Uber, but they “Uber” from one place to another. Indeed, the current CEO of Uber said that he joined the company because it was a verb: “My father always told me if you can run a verb, say ‘yes.’”

With both members of the US ride-hailing duopoly filing initial documentation for their respective 2019 IPOs last month, a closer look at the Lyft vs Uber debate is worthwhile.

What are the Qualitative Differences Between Lyft and Uber?

Although ride-hailing platforms continue to dominate traditional taxis, for both passengers and drivers, it is often a coin toss to decide between the two incumbents. Ride-sharing is a commodity in most US cities, so the majority of both drivers and riders open up Uber and Lyft indiscriminately and choose which to use based on price and wait time. The map applications from Google and Apple have caught on to this and offer in-app pricing gauges for ride-hailing services when users are seeking directions. And some apps have come on to the scene specifically to help users choose the optimal service, such as Bellhop and GoA2B.

While essentially both Uber and Lyft are platforms to pair drivers with riders that want to reach their destination, the two companies differentiate themselves in some ways. Securities analysts drawing up valuations of IPOs do not typically pay too much attention to company culture, however, the stark contrast between these two is illuminating from a strategic standpoint.

Starting with the branding: Uber has a simpler black and white feel, while Lyft opts for pink coloring with a distinct typeface.

Each of their logos reflects their differing origins. Uber initially started as a “black car” service, which lines up with its sleek and business-like aesthetic. Lyft came directly into the consumer market and also originated the carpool feature which gives it a more casual, friendly feel. For most of its corporate history Uber had all capital letters, however in September 2018, Uber changed its logo to remove the all caps for a slightly “softer” appearance.

Aggressive Expansion Gave Uber the Leading Market Share (With Consequences)

In line with its all-business look, Uber did not become the largest ride-hailing platform in the world by playing nice. It brashly established itself as an aggressive “disruptor,” willing to take on taxi unions and politicians head-on in order to enter new cities. Although admired by many, this formula has caused the company to cede market share in its home country of the US in recent years, while it still pursues a rapid global expansion. The first six months of 2017, in particular, was a challenging half for Uber as scandals arose one after the other:

- #deleteUber episode 1: In late January 2017, taxi drivers protested at JFK airport following a sudden increase of US immigration restrictions. In response, Uber turned off surge pricing (to encourage people to use the product) which was perceived as Uber trying to take advantage of those protesting the ban.

- #deleteUber episode 2: Only one month later, Susan Fowler, a former Uber engineer, published an article on her experiences with sexual harassment and gender bias at the company, leading to an internal investigation. Investors criticized the choice of people to internally investigate, suggesting deep-seated issues at the company. Later, Kalanick is filmed berating an Uber driver before he admits that he needs help with leadership.

- Later in February 2017, Uber was sued by Waymo, the self-driving car company spun off by Google, claiming the company stole its key technology.

- Greyballing was revealed in March, a tool to systematically deceive law enforcement officials in cities where its service violated regulations. Officials attempting to hail an Uber during a sting operation were “greyballed”—they might see icons of cars within the app navigating nearby, but no one would come to pick them up.

- Then in March, Uber’s self-driving car program was suspended after a crash in Arizona.

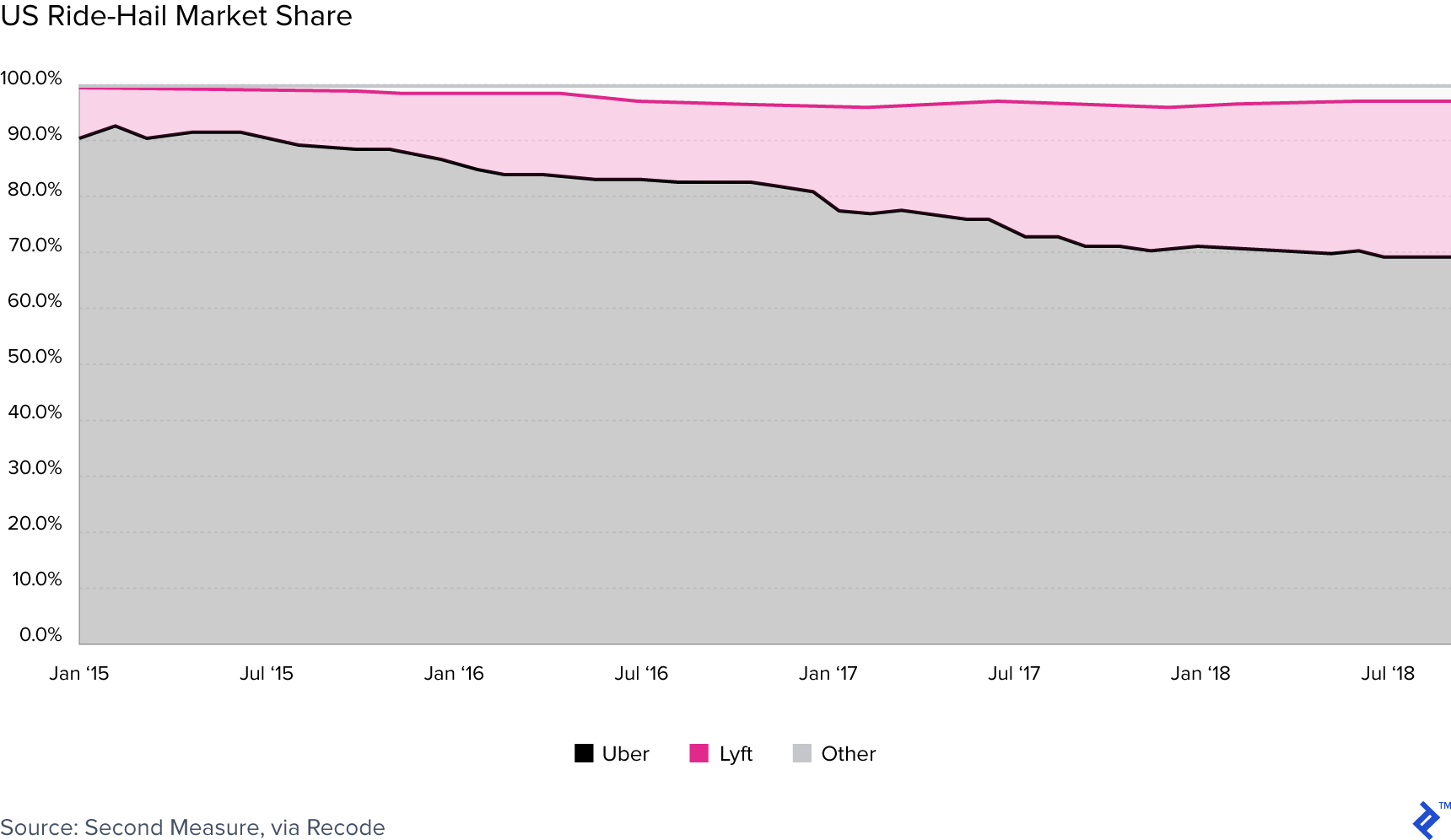

There were twelve full departures of top executives during the first half of 2017, culminating in the CEO stepping down. Among the fallout, Lyft had an opportunity to break Uber’s monopoly just by providing a viable alternative. Note the gap down in Uber market share in early 2017:

As of December 2018, Uber accounted for 69% of U.S. rideshare spending, and Lyft held 29% of the market, up roughly three points from the start of 2018. As both companies battle for market share, they’ve had to spend on subsidies to drivers and offer promotional discounts to riders. It’s a race-to-the-bottom strategy that has caused both companies to burn through hefty amounts of cash—Uber has reportedly spent over $11 billion since its founding—and has struggled to reach profitability. The financials will be covered in more detail later on.

How do Their Business Models and Strategies Differ?

Despite the apparent similarities in business models of the core ride-hailing business, there is a greater strategic war that both players are fighting, with different battles to be won. Lyft only operates in the US and Canada, while Uber has already expanded into over 70 countries, despite recent pull-backs from Asia and Russia. So while Uber is playing for domination of the global market, Lyft is chipping away at the US domestic share.

Are there strategic advantages to being first into a market? Yes and no. There does seem to be something of a first-mover advantage but it appears to be limited to brand-recognition, as loyalty amongst the majority of both drivers and riders does not appear to be very strong (as further evidenced by the new ride-hailing comparison apps). There may actually be a second-mover advantage, as the first into a market has to fight regulatory and political resistance, not to mention cultural barriers, paving the way for those who follow.

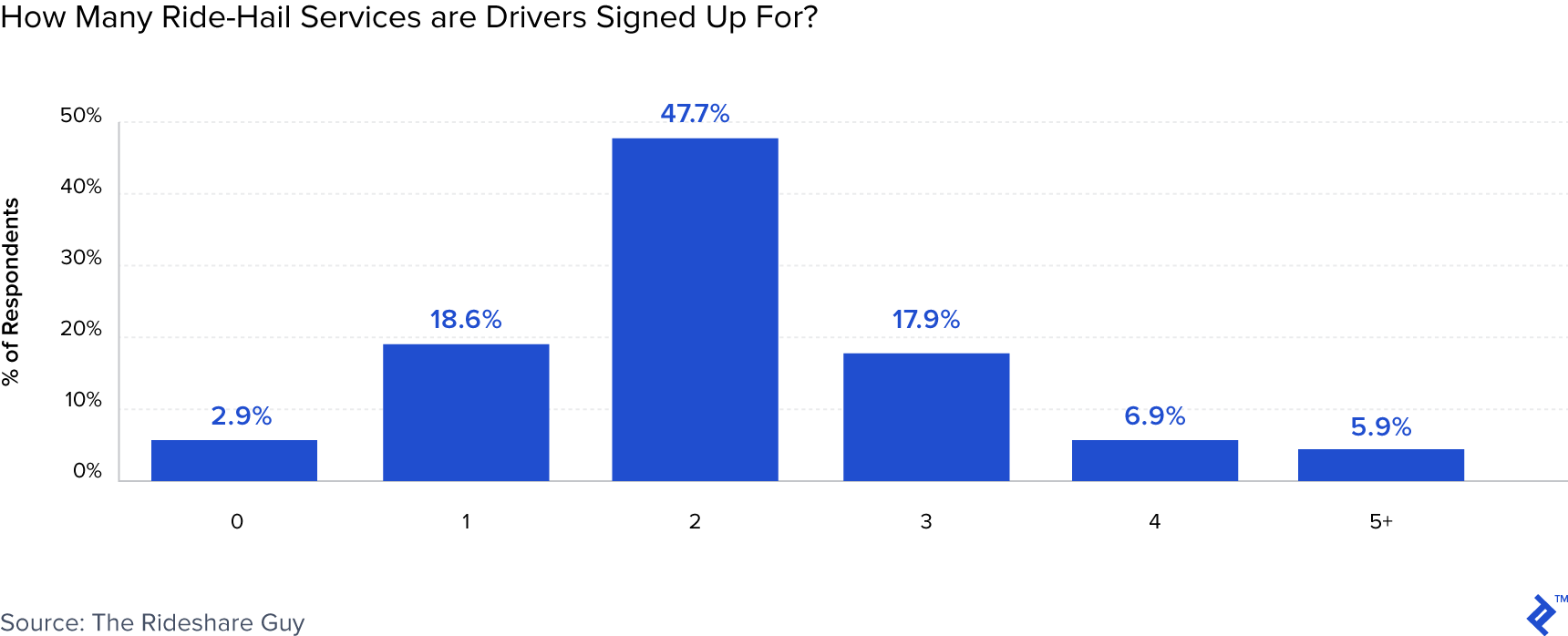

Less than 20% of rideshare drivers are exclusive to one service which demonstrates the lack of both loyalty and switching costs between the services.

There is also an interesting chicken-and-egg dynamic in marketplaces such as ridesharing in which network effects are achieved through the supply side. Aggregating enough driver supply is needed for the service to be viable for riders. However, drivers are not employees and are free to use multiple services, so even though Uber has been first to many markets and has been able to achieve the critical mass of drivers needed, as soon as a competitor, such as Lyft enters, the drivers can easily sign up. In a way, Uber is doing the heavy lifting for the entire ride-hailing ecosystem.

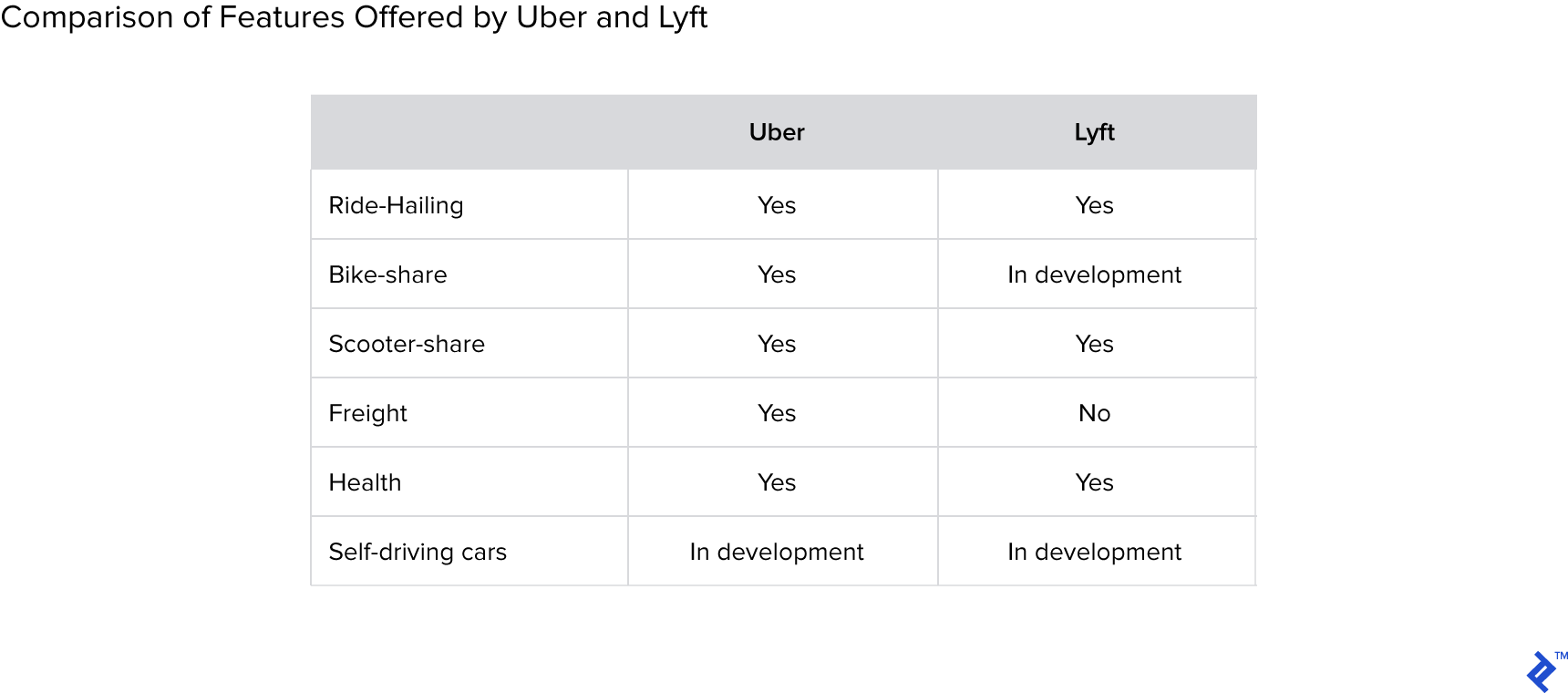

There is a difference between Uber and Lyft in terms of the service suite offered. Uber has a more extensive range of services, with the largest being food delivery, while Lyft is more focused on basic ride-hailing and carpooling. For the first time with its Q3 2018 financials, Uber also broke out Eats specific bookings which the company says accounted for $2.1 billion of overall gross bookings (16.5% of the total) and is growing over 150% per year—far outpacing its legacy business.

Both Have Been Active in M&A Deals

Recent acquisitions also shed some light on the respective strategies:

- In 2018, Lyft acquired Blue Vision Labs, an augmented reality company, and Motivate, a bike share company. The former is related to self-driving cars and the latter is a diversification of how people get around cities when not in a car or public transport.

- Similarly, in 2018 Uber acquired Jump Bikes, a bike-share company. It also invested in Lime, a scooter-share company.

These acquisitions by both companies are in line with their shared aspirations to become one-stop shops for all things transit, with last-mile solutions such as bikes and scooters being an integral component of that vision.

Uber and Lyft are both heavily invested in bringing driverless cars to market. Despite major setbacks, including a fatal accident, Uber continues to press forward with help from an August 2018 strategic investment from Toyota. In May of 2017, Waymo joined forces with Lyft. Lyft also announced a new partnership with auto parts supplier Magna in March 2018, with the intention to work towards driverless cars.

Although further out on the horizon, Uber has ambitious plans for flying cars, opening an entire branch of the company (Uber Elevate) that focuses specifically on developing flying transit systems. Batman had a flying car, but he did not get one until The Dark Knight Rises. Maybe we will soon be seeing hoverboards like in Back to the Future II as well?

Fundraising and Valuation Growth Has Been Consistent

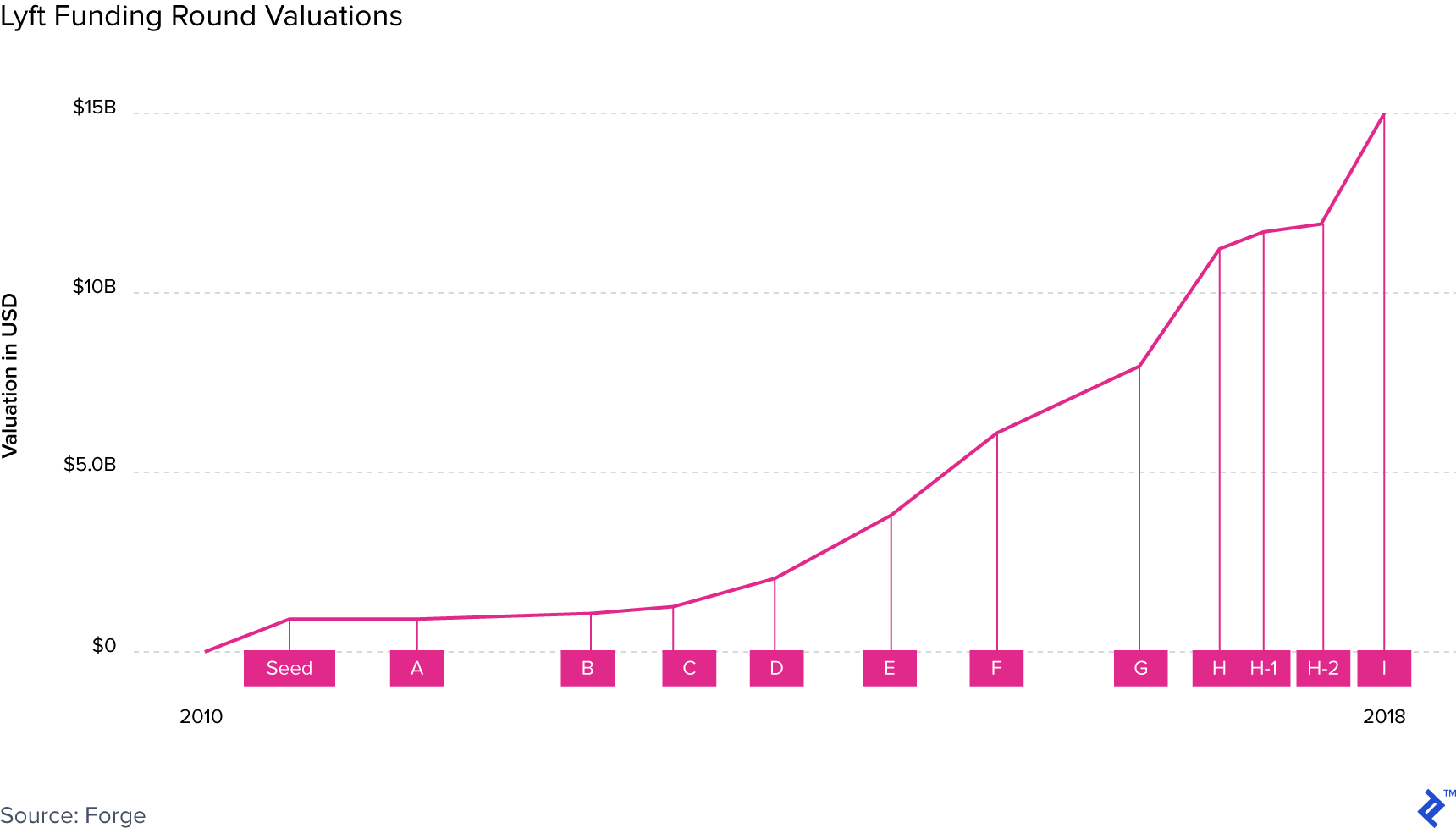

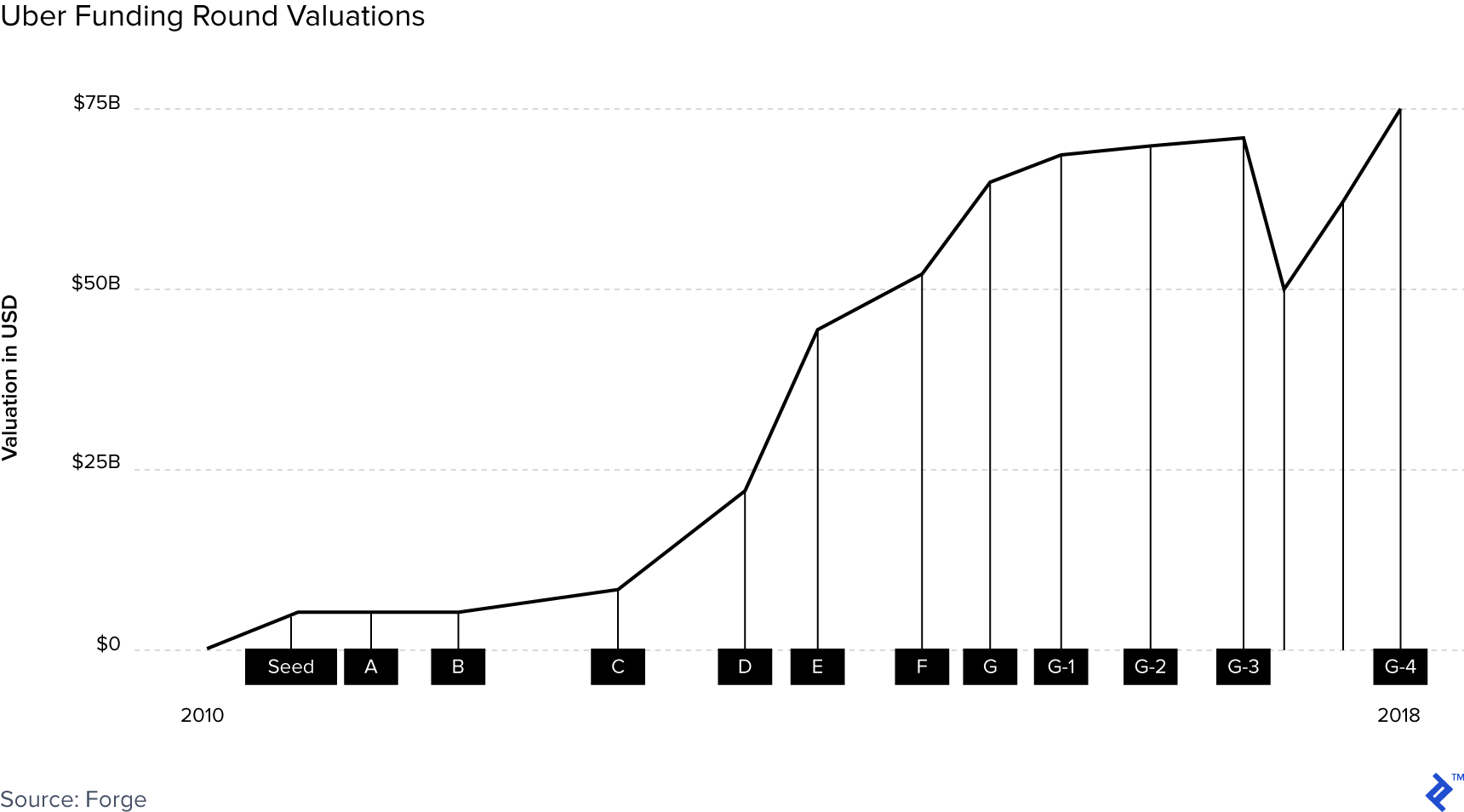

Accompanying both companies’ rapid revenue growth has been rapid valuation increases.

As can be observed from the chart, Lyft has had a steady upward trajectory in its valuation since its founding. The investor base has become increasingly diverse as rounds have increased in value and funding amounts. Key financial investors include Fidelity, CapitalG, Third Point Ventures, and Andreessen Horowitz while key strategic investors include Magna International, GM, and Didi Chuxing (the Chinese market leader in ride-hailing). Note that there is plenty of overlap among the shareholder rosters as many investors in Lyft are also invested in Uber. In point of fact, Waymo accepted Uber shares in compensation for the settlement after accusing the company of stealing trade secrets. That is some way to bury the hatchet!

The recent dip in the valuation of Uber clearly draws one’s attention. At the end of 2017, Softbank led a large $9 billion funding round into the company which was revealing in many ways and merits further discussion. It took many months of painful negotiations to hash out, among the infighting between former CEO Kalanick and lead investors Benchmark Capital. And although all parties tried to paint it as positively as possible, it amounted to that most dreaded of Silicon Valley events: a down round. There was a relatively small amount of $1.25 billion of fresh capital injected at a valuation of $70 billion, but the vast majority of the funds ($7.7 billion) went for secondary purchases from existing shareholders that wanted out. For these, Softbank made a tender offer on the Nasdaq Private Market at a valuation of only $48 billion—more than a 30% discount to the previous round. It was oversubscribed.

One year on, Softbank looks absolutely brilliant. They were able to reorganize the board, put the Benchmark/Kalanick lawsuit to rest, realign some strategic initiatives such as de-emphasizing Asian growth, and effectively purchase two board seats. Softbank also now boasts that it is Uber’s largest shareholder, holding approximately 15% of shares outstanding. Subsequent funding came in at record valuations and with an IPO rumored to be upwards of $120 billion, they are looking at a 2.5x investment with medium-term liquidity.

However, the fact that the tender offer was oversubscribed so recently, at such a discounted valuation of $48 billion, implies that a meaningful number of existing Uber shareholders are looking for liquidity and so Uber shares may suffer selling pressure once the lockup expires—typically six months after the IPO. Uber investors are hoping that soon-to-be free-floating shares will find themselves in strong hands before that happens.

The Uber investor base is made up of a very wide range of both strategic, financial, and even celebrity investors such as Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Ashton Kutcher, and Lance Armstrong. Notable financial investors are the Softbank Vision Fund and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund while strategic investors include Toyota Motor Corp and Tata Capital. It was reported that former CEO Kalanick had sold a large portion of his stake during 2018.

Whereas typically Silicon Valley investors will choose one winner rather than invest in two companies within the same vertical, this is clearly not the case with Uber and Lyft, throwing more weight behind the idea that there is room in the market for more than one player. Alphabet (also via CapitalIG), Fidelity, the Saudi Arabia pension fund, and Didi Chuxing all have investments in both companies. And the fact that Uber is an investor in Didi means that it is an indirect investor in its largest rival!

It’s Still Unclear When/If Lyft and Uber Will Become Profitable

Historical financial information is not officially public so clean and comprehensive figures are difficult to piece together, but both companies have been leaking snippets of their financials as they build hype into their respective IPOs so at least a rough sketch is possible to draw.

It is not surprising that both companies are growing their top-lines rapidly. Lyft is coming from a lower base, but in H1 2018 the company brought in $909 million in net revenue, which is an impressive 121% increase from the prior year period.

Uber is by no means mature in its growth trajectory, but it is not expanding as rapidly as it once was. Q3 2018 net revenue was $3.0 billion, representing an expansion of 38% compared to Q3 2017. In terms of net revenue, based on these figures Uber brings in approximately 6x more than Lyft.

Profits are another story. Both companies are completely reliant on external funding and do not make operating profits, in line with the current Silicon Valley ethos: take market share now, worry about profits later. Lyft’s net losses came in at $373 million in H1 2018, while Uber sustained losses of $1.1 billion in Q3 2018 alone.

The good news for both companies is that they can afford to continue sustaining losses due to their cash hoards which have been amassed through all of the abovementioned funding rounds (alongside additional debt issuances), even without expected IPO proceeds. Lyft has not disclosed how much cash it has on hand, but it has raised nearly $4 billion in equity since late 2015 so even after taking into account the operating losses, we can assume that the company has ample runway. Uber holds a pro forma $9.1 billion in cash as of Q3 2018, after factoring in subsequent equity and debt issuances. Even after considering that the company may have burned over $1 billion in Q4, at this pace, Uber will still have over two years of runway.

Also of note is that Uber holds significant stakes in the Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing from the sale of its China operations in 2016 and in SE Asia ride-hailing operator Grab from the sale of its operations there in early 2018. At the time, the Didi stake amounted to 17% of the company, and although it is held as preferred shares, the stake has likely been diluted through subsequent funding rounds. Nevertheless, Didi Chuxing has also been exploring an IPO, with a rumored valuation of $80 billion, meaning the stake that Uber holds could be worth upwards of $13 billion.

As for Grab, Uber held 27.5% of shares as of early 2018, but Grab has had a huge Series H funding round open since June, bringing in $3 billion at a pre-money valuation of $9 billion. In theory, this would dilute Uber’s stake to just over 20%, leaving it worth $2.5 billion.

How Might Public Markets Value Uber and Lyft?

Let’s begin by examining what the companies have most recently been valued at in private, arm’s length funding rounds, before moving on to see what they might be worth in the public markets. Note that due to the lack of profitability at both companies, revenue multiples is the yardstick most frequently used. But before digging into the numbers, please ask yourself: Which company deserves a valuation premium over the other? Does Uber deserve a superior valuation with its scale and global ambitions? Might Lyft warrant a higher multiple due to its faster growth trajectory?

- Toyota made an investment in Uber at a reported pre-money valuation of $71.5 billion in August 2018, representing a revenue multiple of 7.4x, using LTM Q2/2018 figures. Uber posted a net revenue growth of 63% in that quarter.

- Fidelity made an investment in Lyft at a pre-money valuation of $14.5 billion in June 2018, representing a revenue multiple of 9.3x, based on the trailing twelve months to June 2018. Lyft showed growth of 128% in the first half of 2018.

Looking at these 2018 funding rounds, Lyft appears to have achieved a valuation premium over its rival—likely owing to its superior growth rate. However, turning to current valuations, the picture is somewhat different.

Given the large roster of shareholders and years of equity compensation for employees, relatively active secondary markets have developed for private companies. Equidate is one such platform and can be used to glean a rough idea of what current valuations might be. As of this writing, the platform has a (wide) indicative bid-ask spread of:

- Uber value: $78 billion to $100 billion

- Lyft value: $14 billion to $18 billion

Assuming that the Q4 2018 revenue growth was the same for Uber as in Q3 2018, FY 2018 net revenue will have come in at $11.4 billion. This puts the current trading range at a multiple of 6.8x to 8.8x. As for Lyft, if H2 2018 showed the same growth rate as H1 2018, FY 2018 net revenue will have come in at $2.3 billion for a multiple of between 6.0x and 7.7x—about a turn lower than Uber.

Turning this methodology on its head, applying the same multiple of 7.4x to Uber as was granted during the last funding round in August to estimated revenues of $11.4 billion would yield an enterprise value of $83.8 billion. For Lyft this figure is fully $21.8 billion. As previously mentioned, Uber has been said to be potentially valued at an eye-catching $120 billion in an IPO event which would imply a double-digit revenue multiple.

Summary of Key Financial Metrics of Lyft and Uber

| Uber | Lyft | |

| Countries present | 75 | 2 |

| App downloads (last 30 days) | 25.3 million | 2.8 million |

| Domestic market share | 69% | 29% |

| Estimated gross cash balance | $9 billion | $2.7 billion |

| Net revenue (LTM) | $10.5 billion | $1.6 billion |

| Last reported growth rate | 38% | 121% |

| Net losses (LTM) | $3.2 billion* | $806 million |

| Equidate indicative valuation | $78 billion - $100 billion | $14 billion - $18 billion |

| Implied 2018 revenue multiples | 6.8x - 8.8x | 6.0x - 7.7x |

*Does not include the gain on sale of SE Asia operations.

Lyft vs Uber: Is It Really a Winner-take-all Industry?

The private markets currently seem to favor Uber over Lyft, but is the premium deserved? The two companies are undoubtedly competing for the same pie, but is this a winner-take-all industry? Not really:

- As discussed, there are no barriers to switching on either the supply or the demand side. Drivers use both Uber, Lyft, Via, etc. with no real consequences. Similarly, riders can do the same and continue to switch based on which one provides a better price at the time.

- The business model is easy to replicate and there is no moat. A competitor can copy Uber in any given market and can spend on acquiring drivers to get to a similar level of performance.

- If there were only one player in a market that company could drive out the competition and subsequently increase prices, hurting consumers and arousing antitrust complaints or at least regulatory action by municipal governments. Indeed, squeezing money from rideshare is expected to get harder, as major cities like New York have moved forward with proposals to add surcharges to fares and cap the allotment of active vehicles.

In light of the market environment and faster growth at Lyft, Uber’s premium valuation must be explained by something else. Investors must believe that there is more to the story and are betting on Uber capturing more than just the global ride-hailing market. This narrative of ambition through targeting more global markets and transport verticals appears to have captured investors’ attention more so than Lyft’s slow and steady ascent.

Indeed, Uber appears to have settled on the strategy of killing the personal car and owning every part of the urban transportation ecosystem. And that is exactly the narrative that Uber management and the IPO bookrunners will be telling. Unsurprisingly it has already begun: in a meeting with investors last year, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said, “Cars are to us what books are to Amazon.”

Addendum: Key Takeaways from Lyft’s S-1

Revenue doubled from 2017 to 2018 - a very strong trajectory, which should in theory warrant a premium valuation. However, H2/18 growth showed a deceleration from H1/18 from 121% to 99%.

Underlying the impressive top-line growth are some useful metrics the company has disclosed, which Wall Street analysts will be tearing apart over the coming weeks. Notably, the revenue per rider has increased quite substantially over the past two years – doubling from about $18 to $36. Other useful metrics, such as gross bookings and number of rides are helpful, while invented profit metrics such as “Contribution” are typically cast aside by seasoned analysts. Revenue as a percentage of gross bookings is an important profitability figure, and it has been increasing steadily from 17% to 29%, but there is a limit to this as drivers will not tolerate too high a “rake” from the platform.

This was accomplished while sales and marketing spend increased a relatively modest 42%, although other expenses (COGS, G&A, R&D, etc.) more or less kept pace with the top line.

All in all, investors are going to point to an improving net margin. Losses in H2/18 stabilized around $250 million per quarter despite top-line growth. These losses are relatively manageable, as the current bullish funding environment will happily invest $1 billion per year for such high growth rates. As a reminder, Uber loses about this much per quarter (though to be fair is at a much larger scale). Lyft has cash and equivalents of $2.0 billion on its balance sheet, prior to any IPO proceeds.

Some interesting stats about the market were flaunted to whet investors’ appetites: Transportation is the second greatest household expenditure category in the US, behind housing. And there is plenty of blue sky: In 2016, ridesharing accounted for just one percent of the vehicle miles traveled in the United States.

Some of the shares of the IPO will be allocated quite specifically. Some shares are for friends and family of directors, but then others are earmarked for drivers who have completed at least 10,000 rides. The company is giving a bonus of $1,000 worth of shares to these drivers and a bonus of $10,000 to drivers that have completed more than 20,000 rides. It will be interesting to see if Uber follows suit.

Also of note is that the company looks set to maintain dual voting-class shares, with the Class A shares issued to the public getting only 1/20 of the voting power of Class B shares.

Understanding the basics

What does ride-hailing mean?

Ride-hailing is a sector within the on-demand economy that enables self-employed drivers to use their vehicles to transport customers (riders) that solicit their services via a marketplace app.

Zachary Elfman

Vigo, Spain

Member since January 6, 2017

About the author

Zach is a modelling, fundamental analysis and valuation expert that has managed money for PE and hedge funds. He now runs his own business.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT