How Forensic Accounting Can Supercharge Your Financial Risk Analysis

In an increasingly volatile business environment, companies need to step up their risk management game. Forensic accounting can help spot oncoming problems before it’s too late.

In an increasingly volatile business environment, companies need to step up their risk management game. Forensic accounting can help spot oncoming problems before it’s too late.

Christopher Holloway

Christopher is a Senior Writer at Toptal with 13 years of experience researching and writing about how technology transforms sectors like banking, business, manufacturing, and healthcare. He was previously the business and technology editor at AméricaEconomíca and has developed content for Sony Pictures, Johnson & Johnson, Mini, and LATAM Airlines.

Expertise

Featured Experts

Previously at Johnson & Johnson

A few years ago, Neel Augusthy—a forensic accounting expert at Toptal, who has held regional and divisional CFO roles at Medtronic and Johnson & Johnson—was reviewing a company’s performance at the request of its owner, a conglomerate. As is typical for forensic accounting pros, he blends both quantitative methods and qualitative tools such as conversations, behavioral observations, and site visits in his work.

Augusthy began that particular investigation, as he often does, by reviewing audits of similar companies. He found that the company was much less profitable than others like it and that its profitability didn’t line up with expenditures—both red flags. His next move was to spend a significant amount of time talking and listening to employees and vendors of the company.

Asking questions is crucial to getting people to open up to you, he says. “You almost have to be childlike, asking out of pure ignorance: ‘Can you explain to me how that works? You’re telling me this, and my other source over here is telling me that, so how does it all fit together?’”

When Augusthy talked to the company’s vendors, many complained about low margins, which didn’t make sense, given how much the company claimed it was paying them. So he took the company’s general manager to dinner, under the pretense of catching up and discussing potential improvements.

“When people talk and they feel comfortable, they tell you a lot of things they probably shouldn’t,” says Augusthy. “I asked [the GM] why the vendors were complaining about margins being so low when we pay them so much. He said, ‘Oh, these guys just keep complaining for no reason.’” The GM made some other comments that felt off to Augusthy too: “He’d just ‘bought this piece of land here’ and ‘that one there.’ And I thought: This isn’t adding up. Suddenly he’s got a lot of money to make these purchases.”

“That’s when I figured out he had been skimming from the business by taking money that was due to the vendors,” Augusthy says. As a result of the investigation, the conglomerate removed the manager and improved checks and balances to make sure it didn’t happen again.

What Is Forensic Accounting?

Forensic accountants, also called investigative accountants, are commonly associated with investigating criminal activity, but that’s not all they do. These specialized practitioners are equipped with specific accounting skills and tools to dig into what lies beneath financial statements and uncover other hidden problems and risks, including those related to:

- Fraud: loss of capital due to wrongful or criminal deception.

- Regulatory compliance: taxes or fines due to a failure to abide by laws.

- Liquidity: loss of capital due to excessive debt and insufficient equity.

- Investment: loss of capital due to investing in a troubled business.

- Credit: loss of capital due to lending money to a borrower who is unable to repay.

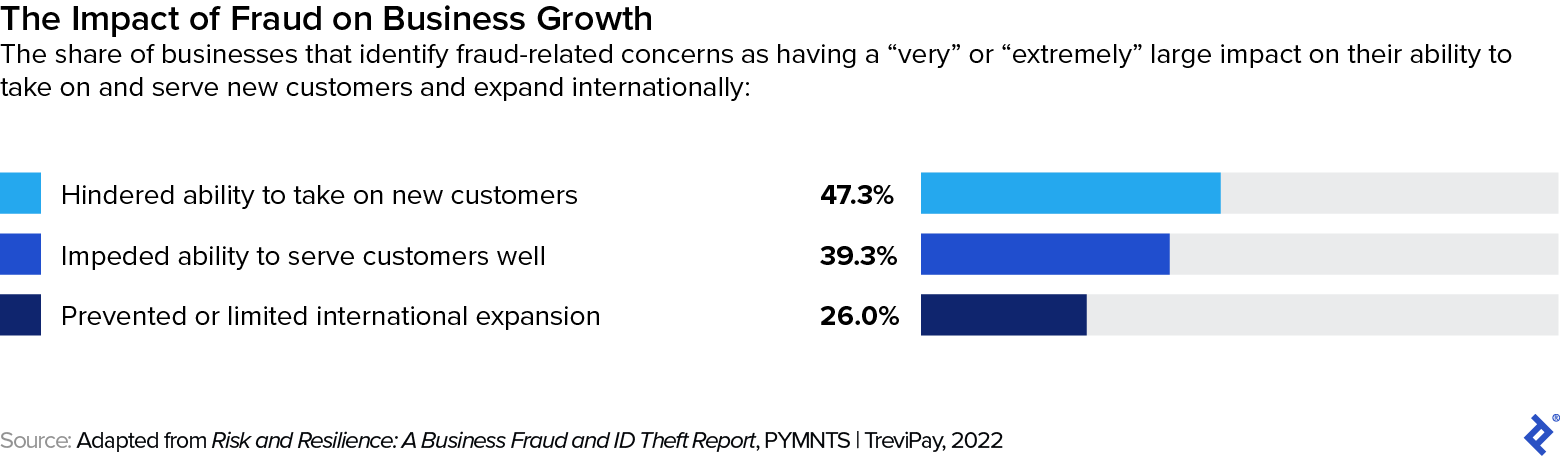

In the more than 20 years since the scandals and collapses of Enron and WorldCom catalyzed the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the corporate risk environment has become more volatile and complex. The speed of technological innovation, the disruption of supply chains, and the looming climate crisis not only make it harder to anticipate financial risk, the increased volatility also provides fertile ground for fraud.

While traditional financial risk analysis methods can be effective in identifying and mitigating many problems, they’re not always sufficient to uncover all types of financial risk. Given the business environment, there’s a dangerous underutilization of forensic risk analysis and management, especially among small to medium-size businesses, says Toptal Chief Economist Erik Stettler. In his previous work for NERA Economic Consulting, he studied the failures and near-failures of a number of prominent US institutions during the Great Recession.

Many companies try to save money by running less-rigorous checks with in-house staff, Stettler says, but that is risky because staffers may not have the necessary experience or may be so accustomed to the way business is done at the company that they fail to spot red flags. Failing to identify fraud, violating regulations, or shrinking liquidity cost a company far more than the upfront capital outlay for specialized investigative accounting, which typically ranges from $30,000 to $50,000 per project, he says. In contrast, a December 2017 study of multinational organizations found that the average annual cost of noncompliance was nearly $15 million.

Forensic Accounting for Financial Risk Analysis

Investigative accountants do more than examine financial statements. These specialists approach investigations holistically, incorporating statistical analysis, market research, photographs or visual inspections of facilities, conversations with human sources, and studies of individuals’ and companies’ histories, behaviors, and psychology to uncover the truth. For example, to examine a business’s income or expenses, rather than just look at annual or quarterly financials, forensic accountants may ask for real-time numbers for the time period in question in order to observe fluctuations in more detail.

“When considering a loan, an investment, or an M&A deal, or when conducting an audit, it’s critical to take a more granular look beyond traditional financials and also consult, in depth, other sources of information about a company,” Stettler says. But risk managers can’t just send a forensic accountant on a fishing expedition to see what they turn up. Forensic accounting is a significant investment and requires that there be specific claims or concerns to investigate.

A risk management framework can provide companies with a structured approach to identifying, assessing, and mitigating various types of risk, including whether to engage a forensic accountant to dig deeper. When the framework flags financial irregularities, such as unusually high repayment activity by borrowers, it might trigger a forensic investigation. That’s because higher repayment figures indicate a significant increase in revenue for the borrower. A forensic accountant would investigate whether that sudden windfall could be tied to fraud. Let’s look more closely at how investigative accounting techniques can apply in three major risk areas.

Forensic Accounting and Fraud Risk

When looking into questions of fraud, investigative accountants typically ask themselves what they would expect to see if all is well, just as a physician might review a patient’s vitals with a “normal” benchmark in mind. Then they assess statistically whether what the company is reporting matches up, Stettler says.

Just as Augusthy did, investigative accountants also look at whether certain transactions or financial statements are based on persuasive economic and financial logic. If a financial record reports that an asset was sold for 100 times more than comparable transactions or an independent valuation suggests, the transaction may still be valid in the strict sense of the word—but it represents a suspiciously large departure from economic logic. In that case, not only should that transaction be scrutinized but so should others, to see if there’s a pattern.

When investigative accountants have historical data, another key step is looking at statistical structural breaks, such as changes in the way that an asset was priced or in how cash flows or earnings occurred. “This generally entails looking at the correlation of financial or stock price performance versus benchmarks and seeing if there is a point at which the relationship breaks down or changes, meaning financial activity within the company is now being driven by something other than market factors,” Stettler says.

Comparing earnings history against analyst consensus expectations is another tactic. When companies consistently beat consensus by a small margin, that success may reflect legitimate decisions related to depreciation or when to recognize revenue, but it may also hint that they’re managing their earnings to produce financial statements that reflect a rosier picture. Either way, Stettler says, a consistent margin like this can signal a need for a closer look.

Forensic Accounting and Regulatory Compliance Risk

When it comes to staying in full compliance with government regulations, companies face a range of risks, including those related to disclosure, minimum-wage laws, mandated time off, and tariff and trade policy changes. These risks are particularly acute when a company maintains a presence in more than one state or country.

With increasing acceptance of remote work, more and more companies face significant regulatory compliance risks tied to work-from-anywhere arrangements, explains Toptal finance specialist and remote work expert John Lee. These compliance risks, which can result in significant monetary losses, touch on a wide range of areas, including taxes, immigration, insurance, talent management and benefits, and data privacy and security.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses are taking greater advantage of remote work talent pools outside of their immediate metro areas. But applicable tax laws are complex and differ from country to country and state to state, Lee says, and companies that offer robust remote work opportunities would do well to enlist forensic accountants to assess and help mitigate financial risks associated with cross-border hiring and digital nomad workers.

For example, a company could incur additional corporate or income tax burdens if an employee stays in another country or state long enough to inadvertently establish residence there. Moreover, an employee’s extended stay may even constitute a permanent establishment of the business in that area. Any company looking to invest in, merge with, or acquire a firm with remote work policies should also hire one or more forensic accountants to ensure the businesses are in compliance with tax and employment regulations, Lee says.

To help companies with remote employees manage regulatory compliance, risk professionals use a remote work tax risk matrix that shows the individual tax, corporate tax, Social Security, and employment law risks of activities, including setting up a legal entity, hiring via an Employer of Record, hiring a contractor, and employing a worker on a digital nomad visa.

Forensic accountants are uniquely qualified to find potential tax risks involved with remote work and advise companies as to when they need to consult a tax expert for a particular country, Lee says. “Nobody is expected to suddenly be a tax expert in every country in the world. But at the same time, if the company has 15 senior sales people spending six months working in the south of France, or if your CTO is employed via an Employer of Record, then you need to at least flag that this is something that likely requires tax expertise.”

Forensic Accounting and Liquidity Risk

Having investigative accountants check out a company’s books as a stress test—much as white-hat hackers try to breach corporate networks—is a smart way to mitigate liquidity risk, Stettler says. He’s become an advocate for such a proactive approach after spending years analyzing major crises and disruptions in the securities markets and private transactions. Whenever one of these events occurred, NERA Economic Consulting, the firm he worked for, would look into what had really happened versus what ideally should have occurred.

When Stettler helped investigate a large US bank that collapsed during the subprime mortgage crisis, he performed a deep dive into the company’s transaction portfolios, the risk levels their counterparties had accepted, and how aware of the risk those counterparties were or should have been. He also looked into whether the risks taken were in line with the bank’s stated frameworks for leverage and asset diversification.

“Our role in cases like the collapse of that bank was also to help the counterparties understand their exposure to the risk of fallout from the disaster,” he says. “CEOs of some of the world’s largest financial institutions had little idea what their level of vulnerability was.” That’s because their portfolios and hedging strategies were so complex and varied that it was impossible to encompass them adequately in the usual top-line financial statements, he explains.

There were also managerial decisions that inadvertently created vulnerabilities. In the case of the aforementioned bank Stettler was investigating, an intense quarterly performance review process incentivized employees to set extraordinarily high targets that allowed unexamined risk to accumulate below the surface. No one thought to examine whether that incentive structure might create ripple effects throughout the bank’s operations and transactions. The bank’s risk formulas were also part of the problem, since they vastly underestimated the probability of housing prices declining together and at such a magnitude. For the best results, those risk analyses should have been conducted by outside experts using different models to avoid catastrophic blind spots, Stettler says. Surfacing these risks would have empowered companies to address them before they became a problem.

Going forward, he says, as business struggles to keep up with evolving technology and regulation, it’s likely that the International Financial Reporting Standards, or principles-based accounting, will increasingly dominate rules-based accounting, as embodied in the US approach called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

Since the principles-based method provides a more sophisticated and adaptable means to convey underlying economic truth and involves deeper questions than which boxes have been checked, financial risk analysis will probably require more investigative accounting. And that, Stettler believes, is a big part of why demand for these services is increasing, a trend he predicts will continue.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is the purpose of financial risk analysis?

Financial risk analysis is the systematic process of identifying and evaluating risks to the financial well-being of a company. Periodically conducting these checks helps a business anticipate problems and prepare to address them.

How is financial risk evaluated?

Financial risk is typically evaluated by modeling different scenarios such as a drop in sales or a rise in prices along the supply chain. By examining the impact of variations in critical areas, a business can plan ahead for potential challenges.