Startup Financing for Founders: Your Companion Checklist

Attention on the financial aspects of startups tends to focus on the external measure of fundraising. Yet before this, there are many aspects for an entrepreneur to consider regarding setting their business up for financial success.

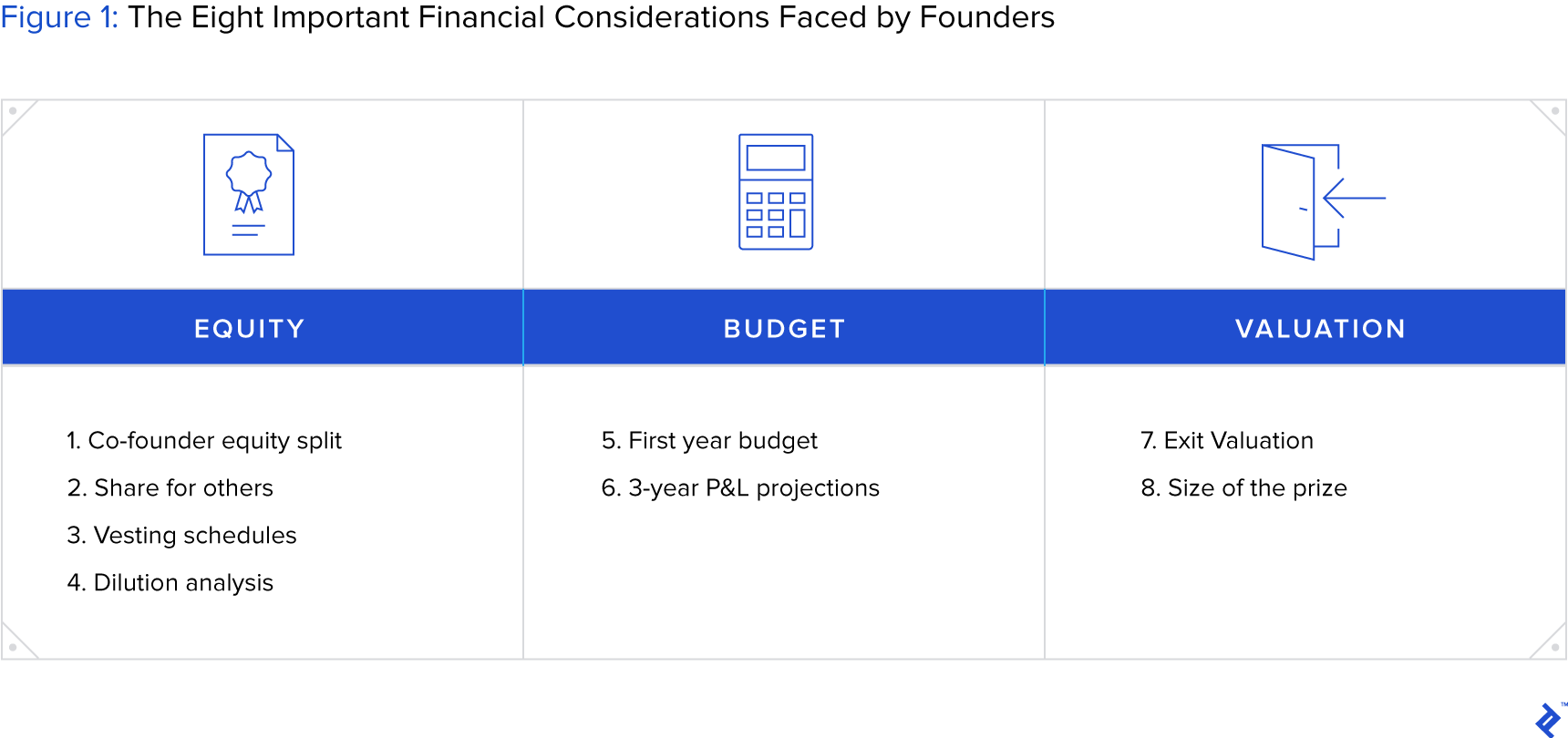

In this article, we address eight vital considerations to take around the equity, budget, and valuation components of a startup.

Attention on the financial aspects of startups tends to focus on the external measure of fundraising. Yet before this, there are many aspects for an entrepreneur to consider regarding setting their business up for financial success.

In this article, we address eight vital considerations to take around the equity, budget, and valuation components of a startup.

A Wharton MBA and CFA, Carolyn has executed 20+ VC/PE deals, managed a $700M portfolio and is a fundraising, growth and M&A specialist.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Executive Summary

Why are Founder Finances Critical?

- Having a complete understanding of their startup's financial situation helps entrepreneurs to be more proactive and credible when soliciting investment.

- 75% of founders make no money from the eventual exit of their startup after raising startup financing.

- A balanced opinion with weight away from the emotional/qualitative aspects of starting a business ensures that entrepreneurs take rational and well-judged decisions.

Understand How Equity Works and Is Divided

- Decide on an equity split among co-founders with a view toward the value of their future efforts. Take any previous work done as a separate sunk cost.

- Be aware that equity might be required for non-co-founders, such as senior hires, advisors, and service providers.

- Ensure that vesting applies over four-year periods to continually incentivize stakeholders and prevent dead equity.

- Control and wealth can be mutually exclusive in a startup. Understand that dilution is necessary and losing control over time can be positive towards achieving financial success.

Take Budgeting Seriously and Have a Long-term Mentality

- Planning out your entire first year will ensure that you are getting into a venture that has merit and that, if you do require financing, you raise the optimal amount.

- Knowing from day one what metrics will determine the success of the business will allow you to build a budget for later years. This serves as both a guide and a milestone marker.

Keep Valuation at the Forefront

- Appraise the likely endgame of the company through potential exit scenarios. Knowing the optimal route to exit in advance will allow for you to tailor your plans for the business.

- Applying knowledge of ownership, dilution, and valuation will ensure that you are aware in advance of your potential windfall from a sale and prevent any nasty surprises.

- Understand your opportunity cost that you are giving up by leaving the labor force. You must ensure that your potential gains from the business outstrip other work options available.

As a startup founder of an early-stage technology company called VitiVision, I recently went through the challenging process of setting up a business, raising funding, refining my business model, interviewing customers, and recruiting a team. Even as a CFA charterholder, former investment banker, and VC, I realized during the process that there were many financial considerations that I wasn’t aware of or ready to make. Startup advice that I gathered from internet research was also fragmented, legally oriented, or biased towards a VC perspective.

In light of these experiences, I will now share with you my learnings in the form of a checklist of the eight important financial considerations that you will encounter as a founder. These are categorized under the themes of equity ownership, budgeting, and valuation considerations.

Why is it important to get “Founder Finances” right?

- It makes you look credible in front of investors and enhances your fundraising success rate and speed. Most investors will eventually ask you to provide much of the information below.

- It sets you up for personal financial success. If you eventually sell your business, don’t be the “75% founders” who don’t make a dime when they take VC money.

- It gives you logical and quantifiable guidelines to back your own decisions. For example, should you pursue your startup, or keep your full-time job? How much funding do you need to raise?

Firstly, You Must Understand the Mechanics of Equity for Startup Founders

How much equity you and other stakeholders will have, and when, is one of the most important financial decisions you will have to make as a startup founder. It’s important because equity provides financial rewards and motivation for co-founders, employees, advisors, and service providers. It also determines decision rights and control of the company.

Getting this wrong could not only risk underperformance and resentment among stakeholders but also result in your own termination from the company or dilution to an insignificant level.

How Do I Split Equity Among Co-founders?

Most likely you will begin your journey with a co-founder, or recruit one shortly thereafter. You will need to decide on the equity split as soon as possible.

Regarding the equity split, there are many articles written on this topic and various online calculators (e.g., here and here) to help you determine the exact amount. The broad factors determining the split should be:

- Idea: Who came up with the idea, and/or owns the IP? While the initial idea is important to start, the execution thereafter is what makes a company last.

- Contribution to the company: Consider the roles and responsibilities of each person’s job, their relative value to the company, and their importance as signaled by investors. The commitment level is also vital and necessary if anyone is working part-time.

- Opportunity costs: How much would each co-founder earn, if they were to find a job in the open market?

- Stage of the company: When does the co-founder join? The earlier they do, the riskier it is, and thus, deserving of more equity.

- …or a simple 50/50 split, as advocated by Y Combinator, 50/50 split promotes equality and commitment, and is “fair.”

Whatever model you use, remember that the split should be forward-looking, in that it should reflect the “future value” of the company.

I made an initial mistake by basing my startup’s entire split calculation on a backward-looking, “How much work has been done to date?” method. In my case, that model gave the co-founder who invented the IP, but was only working as a CTO part-time, a disproportionately larger equity stake (>60% vs. typical IP licensing deal of only 5-10% equity) than my own. I was the one who created the entire business plan, pitched successfully for funding, and was working as the CEO full-time. The missing part of this decision was that it didn’t reflect the forward-looking elements of risks and potential contribution.

Instead of deciding the equity split up front, another approach is to just wait and see. In reality, startups and personal situations evolve quickly. Leave 15% or so of founders’ equity un-allocated for the future, and decide only when you reach the first significant milestone (e.g., MVP or first investment).

In summary, my practical advice from experiences with equity:

- If you are the CEO, you need to have the majority (>50%) of the equity, so you can control the business and make critical decisions.

- If you take a senior role full-time, you need >25% of the equity for a significant “skin in the game” element and to be considered a “co-founder.”

- You need to be prepared for founder departure (including yourself) and have a Plan B to keep the business alive, such as having either a vesting schedule or clauses forcing co-founders to sell x% of equity to a new co-founder for quitting.

- Even if you “wait and see” to determine the final amount, you should have a discussion early and have all co-founders sign a non-binding “co-founder agreement.” You’ll be surprised, no matter how committed and prepared people think they are, that until they have to sign anything (even non-binding), they can always change their minds. This was what I experienced when my former co-founder dropped out after months of working together.

Do I Need to Allocate Shares to Non-co-founders?

Over time, as you grow the team, you will need to give shares to employees, to incentivize their performance. Most VCs will also ask you to establish an employee share options pool (ESOP) and to top it up over time. Typically, at Series A, VCs will ask you to put in ~10% to the employee share options pool. Over the next rounds, investors might ask you top it up to 15-20%.

How much to give, and when, depending on the stage of the company and the seniority of the employee. Common practices are:

| Position | Suggested % | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Senior Hires | 5% | For C-suite or important hires with salaries > $100k |

| Engineers | ~0.5% | Assume a minimum salary of ~$100k. Or if you are in Silicon Valley, all-in expense for a good engineer is ~$15k per month. The lower the salary, the higher the equity needs to be. This tool is useful for determining employee equity compensation. |

| Service Providers | 0.1% ($10k of services at a $10m post money valuation) | Some lawyers might provide services for equity consideration via convertible notes. |

| Advisors | 0.5 - 2% | Depending on their value and commitment |

Vesting Is Insurance: Use It as a Carrot on a Stick

Vesting schedules are put in place to protect other shareholders against early leavers and free riders. As co-founder, unless you have a milestone-based vesting schedule among the founding team, the usual vesting schedule is four years, with one-year vesting cliffs for 25%, and 1/36 of total eligible shares earned each month for the next 3 years. There are variations to this term, such as accelerated vesting, vesting cliffs, and percentage founder vesting earned before outside investors.

How Will Startup Financing Dilute My Ownership Along the Way?

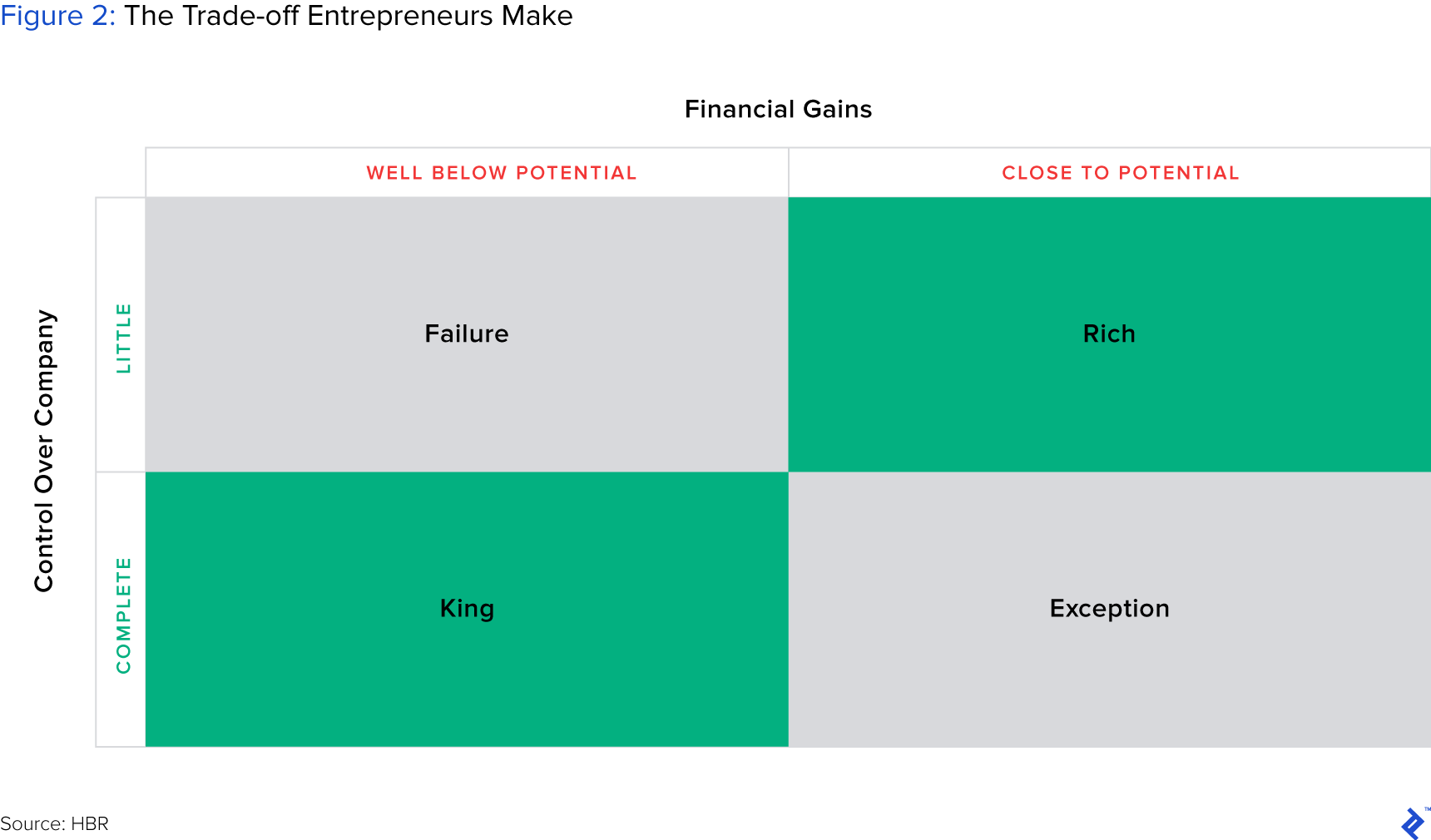

You want to retain control throughout and have a healthy financial windfall when your company exits, right? Sadly, statistically, four out of five entrepreneurs are forced to step down as CEO during their tenures. The HBR article The Founder’s Dilemma argues that the control vs. wealth dynamic is usually a rich vs. king tradeoff. According to the article:

The ‘rich’ options enable the company to become more valuable but sideline the founder by taking away the CEO position and control over major decisions. The ‘king’ choices allow the founder to retain control of decision making by staying CEO and maintaining control over the board—but often only by building a less valuable company.

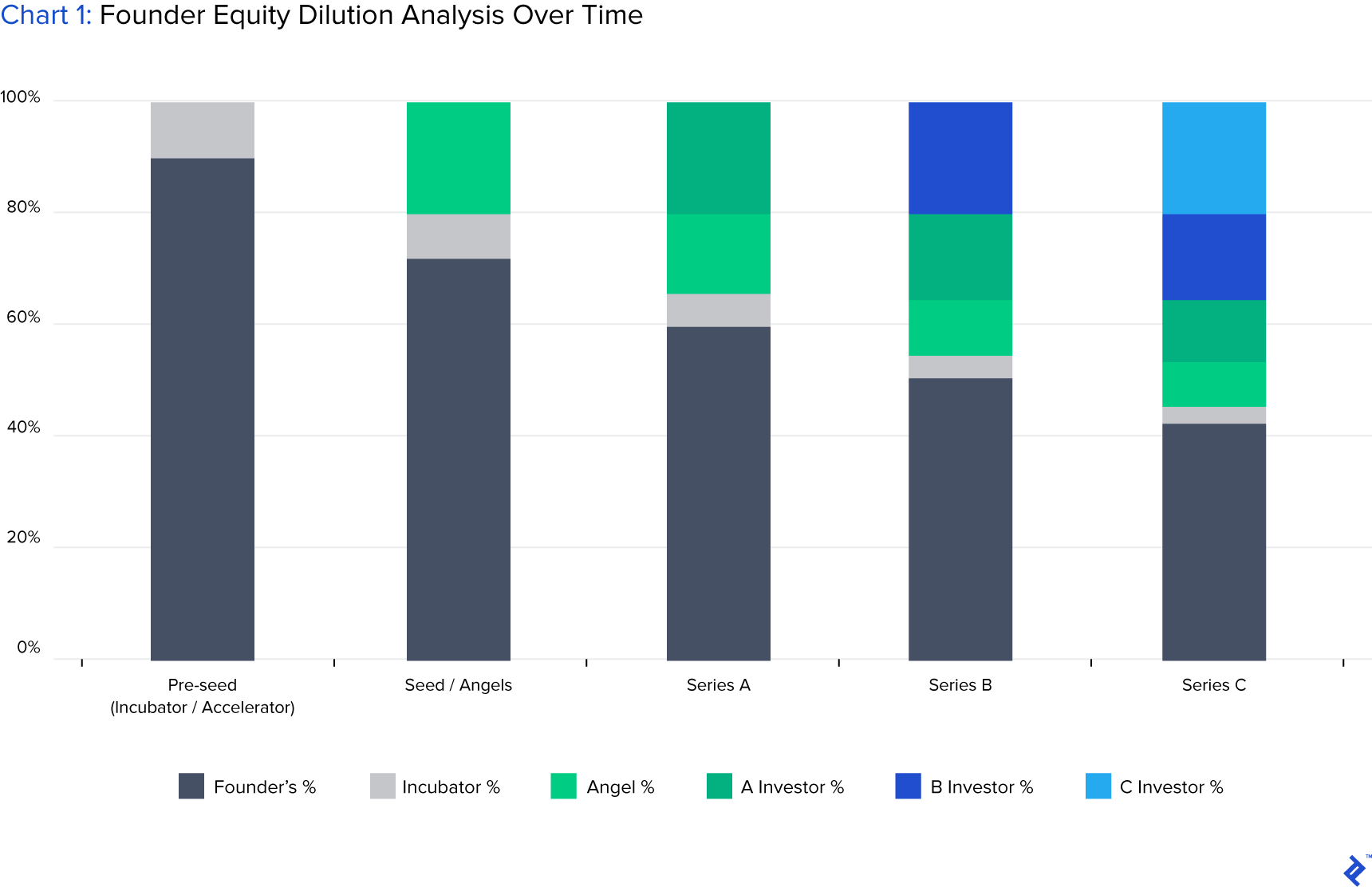

This article highlights how important it is for you, as the founder, to understand dilution and its impact for you as early as possible. After multiple rounds, you could end up with less than 30% of equity at exit; however, the value of your stake could increase significantly at each round.

You can do a dilution analysis by developing a pro-forma capitalization table (called a “cap table” by VCs) and continually updating it. The important input assumptions are:

- Financing needs or money raised (depending on your burn rate)

- Number of rounds

- Dilution in each round (new investors + ESOP)

The output of this analysis should be the founder percentage ownership at each round and the dollar value of the equity. What should you assume? Here are some typical assumptions you can make, followed by a demonstrative example (Table 2 and Chart 1):

- Successful startups need 3-5 investment rounds before exit. The more rounds you raise, the more dilution you take.

- At each round, a new investor will ask for 10-25% of equity (dilution), and a top-up of employee share options (ESOPs)

- Round size increases by ~5x between each financing round

| Pre-seed (incubator/accelerator) | Seed/Angels | Series A | Series B | Series C/Pre-exit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-money Valuation | $1.0 | $2.5 | $12.5 | $62.5 | $312.5 |

| Money Raised | $0.1 | $0.5 | $2.5 | $12.5 | $62.5 |

| New Investor % | 10% | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| New ESOP % | 0% | 0% | 10% | 6% | 5% |

| Founder's Equity Value | $0.9 | $1.8 | $6.3 | $23.3 | $87.4 |

Secondly, Take Budgeting Seriously and Have a Long-term View

Budgeting sounds boring, but doing it right ensures that you make rational decisions from day one and don’t let your biases cloud your execution.

A Robust First-year Budget Will Ensure That You Raise Enough and Don’t Waste Money

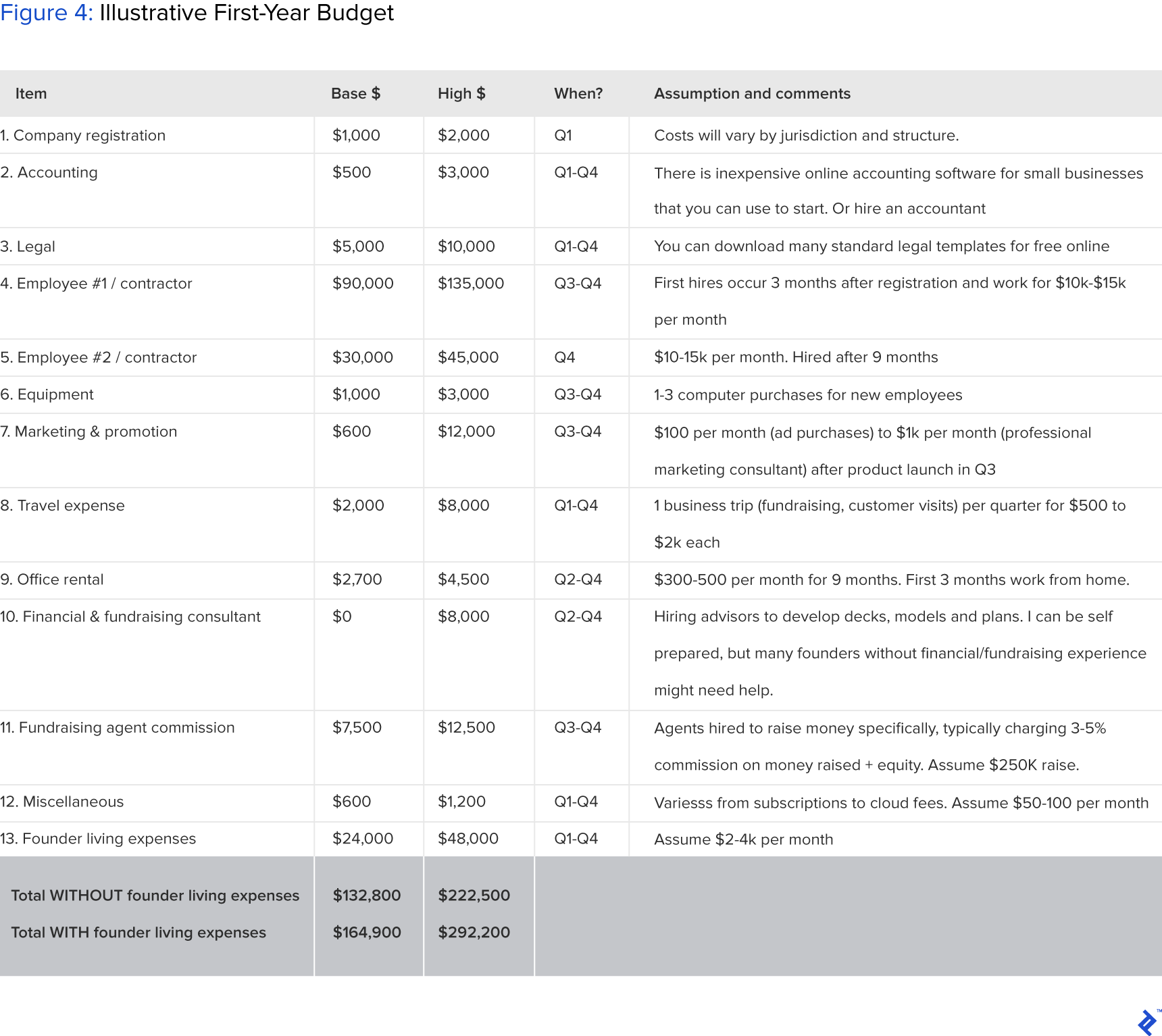

It’s important to have a clear estimate for the first-year budget so that you know how much you can self-fund or if you need to raise investment. The cost items on an initial budget should include:

- Company registration and incorporation: ~$1k.

- Accounting: $2-3k for a solo accountant on a one-year retainer.

- Legal: ~$5-10k. Hiring a good lawyer can be priceless, as famously shown from the experiences of Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin. From personal experiences, my lawyer pointed out a clause in my investor’s shareholder agreement that could have forced me to sell all of my shares to investors in the event of a dispute (the “shotgun” clause). Don’t sign anything with an investor unless a lawyer has seen it first.

- First Employees: only bring them on when absolutely necessary, use contractors in the interim.

- Other: travel expenses, office space, and equipment.

- Founders’ living expenses (don’t forget this!): These should be included in your internal budget version (not for outside investors), if you are full-time and not drawing a salary.

| Timeline | Activity description | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | First 3 months | Company registration, pre-seed fundraising, business plan, pitch book, co-founder negotiation. |

| Q2 | 3-6 months | MVP development, customer validation, marketing, first hire |

| Q3 | 6-9 months | Seed fundraising, second hire, product launch |

| Q4 | 9-12 months | Traction building, trying to survive |

In summary, a realistic first-year budget for a startup of non-paid co-founder(s) and one FTE (contractor or employee) is in the range of $160k to $300k. You should have the confidence to raise this or be prepared to fund it yourself. There are some alternative funding sources out there, such as incubators or accelerators, where they either invest an initial amount or provide FTE resources, such as technical engineers, to help you develop an MVP and kick-start the venture.

Have a Three-year Startup Financial Model to Plot Future Milestones

This should be done in conjunction with a desired exit valuation (discussed in the next section) so that you can realistically project the next three years of P&L in lieu of an end goal.

I suggest that you focus on major items: milestones, key metrics (e.g., number of users), revenues, and expenses, as your business can pivot drastically during its life. Make assumptions and document them in detail so that you can continually iterate.

- Major milestones. What are they, and when will they be hit? For example, they can be your first hire, MVP, first customer, and/or seed round.

- Key metrics (other than revenues) such as the number of users, full-time employees or regulatory approval. This is especially important if you don’t envisage having revenues for a period of time, which can be common in sectors such as biopharma.

- Cash burn rate (expenses). What do you have to pay to keep your business alive?

- Revenues. Estimate revenues by making assumptions based on the number of customers, revenue per customer, and growth rate.

Thirdly, Get in the Mind of the Investor by Considering the Valuation of Your Business

As ex-VC and banker, I love building valuation models. It gives me a range of returns that I can expect as a professional investor. And It’s fun—I can build a model valuing a company by playing with assumptions such as market size (TAM/SAM/SOM), growth rates, and exit valuation multiples. Usually, I would project out three potential scenarios:

- Base (e.g., user base grows by 20% p.a.)

- Upside (e.g., viral user growth of 200% p.a.)

- Downside (e.g., first customer in 2 years)

Now as an entrepreneur, I find it even more necessary to build valuation models, as it allows me to estimate the expectations placed on myself. Most importantly, as an early-stage entrepreneur, I can use the exit valuation analysis to steer my business towards:

- Charting the strategic roadmap given my vision. For example, the model should tell me what milestones need to be hit by when.

- Providing confidence for investor pitches. For example, I can say “According to my model, this is a $500 million business you’re investing in.”

I don’t want to discuss here on how to value at each round because valuation at earlier rounds is usually out of the founder’s control and driven by supply and demand of capital. You can find many good articles written online on different valuation approaches for early rounds, such as this one.

Instead, I want to talk about exit valuation and founder’s return projections, which are usually overlooked but important to analyze.

Take a View of Your Exit Scenarios and Build Toward Them

Exit valuations, if considered in advance and done properly, can help you to carefully plan the business’s path. Below are a few critical assumptions that will drive your valuation, exit value, and commercial strategy:

What metrics do you have to hit to achieve an exit? For example, if you are a new drug development company, you need to get FDA Phase II approval to be acquired by a major drug company, or IPO.

When can you hit the target metrics? This puts a ballpark number on the timing of exit. Typically, it takes at least five years to build a viable company.

How would you exit, IPO or M&A? This might sound too premature to think about, but it’s not. If you are targeting M&A, you need to build a company to be a valuable potential asset to the acquirers. For example, if you are building an electric vehicle startup targeting to be acquired by Tesla, you should get familiar with Tesla’s business strategy and technology pipeline. On the other hand, an IPO candidate needs to appeal to a wide range of institutional investors who don’t have specific needs but require an exciting story.

What’s the typical industry valuation approach applicable to your business? The main valuation approach for any financial models is discounted cash flow (DCF), public comparables, and precedent transactions. You can obtain a detailed approach from various finance textbooks and online tutorials.

Consider Your Own Potential Financial Windfall and Use It as a Motivational Barometer

Even though money is not the most important driver for starting a business, you will want to be properly rewarded for your blood, sweat, and tears. Now that you have projected out your expected equity ownership at exit and you know what your target valuation is at exit, you can calculate your return:

Your return = the expected equity % at exit x the target valuation x (1-capital gains tax rate).

For example, if you expect to own 20% of equity at exit, at a $100 million valuation, and your capital gains tax rate is 25%, you will earn $15 million from the transaction.

If you’re debating whether to start this business or not or try to convince someone else to join you can use this analysis to show the potential reward.

It is vital before starting a business that you compare this projected figure versus your own opportunity cost of earnings potential staying in the corporate world. Having this foresight will ensure that you start your business without any regrets and a clear understanding of what you are aiming to achieve.

If Planned Thoughtfully, the Internal Aspects of Startup Financing Will Set You Up for Success

You should be aiming to do this analysis as soon as you are confident about your startup idea and co-founder selections, or at the very latest, before raising external financing.

Many startup founders prefer to focus on building a great business first and then figure out the housekeeping over time. However, it could be even more time and money wasted later if you don’t get it right at the start. For example, we all know about Facebook’s co-founders’ nasty fight, and Zipcar’s co-founders’ not being properly rewarded for their hard work (of the $500 million acquisition of Zipcar, one co-founder only had 1.3% equity after multiple rounds of dilution, and the other had less than 4%).

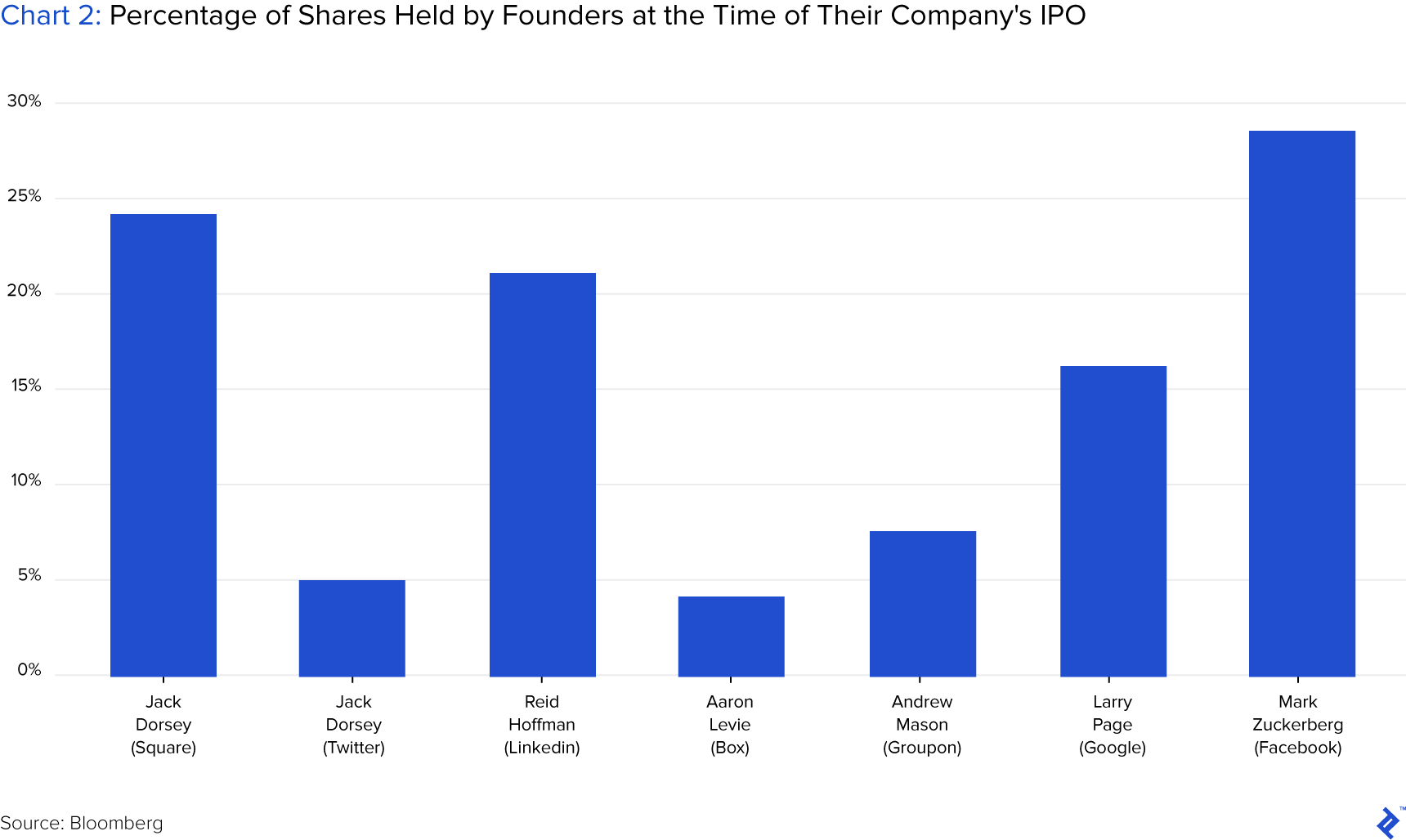

Looking at some examples from founders of famous companies, there is a wide disparity of ownership percentages held at the time of IPO. This shows that there is no set course to take and that personal fortunes are not entirely correlated to the company’s.

In conclusion, like tax and death, these financial considerations don’t go away. It’s better to learn how to deal with them up front or get professionals to help you do this. This will empower you to focus on actually building a great business, from “lean startup” product development to acquiring customers.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is founder equity?

Founder equity is the ownership that is held by the team that started the company. The original capital to start the company will come from founders’ own funds or ‘sweat equity’ that they put into getting the idea off the ground.

What is vesting of equity?

Vesting represents time milestones used to release equity to stakeholders over a set time period. Often, metric targets or timing are used as the rule for releasing shares in this manner. Vesting is applied as a means to ensure that interest and effort from stakeholders is maintained as a reward for equity.

How do shares get diluted?

The dilution of shares refers to the percentage ownership of the holder falling, it does not refer to a reduction in the number of shares held. As companies grow and raise financing, they issue new share capital, the effect of which dilutes older shareholders through the increased pool of stock available.

What is the exit value?

The exit value is the financial consideration given to a startup, or private business, in the event of a transaction that materially alters its ownership structure. This can come from an IPO, M&A, or ultimately a winding up of the business’ affairs

Carolyn Deng, CFA

Singapore, Singapore

Member since July 20, 2017

About the author

A Wharton MBA and CFA, Carolyn has executed 20+ VC/PE deals, managed a $700M portfolio and is a fundraising, growth and M&A specialist.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT