Selecting the Right Valuation Method for Pre-IPO Startups

Valuation for mature late-stage startups can be tricky: Too developed for guestimate methods, yet still without the depth of data offered by public market companies.

Valuation for mature late-stage startups can be tricky: Too developed for guestimate methods, yet still without the depth of data offered by public market companies.

Bertrand is a finance veteran and startup advisor, with a 20-year track record advising 50+ clients on $16 billion of deals.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

In 2019 we are seeing some famous private startups finally list themselves public through the IPO process. Company valuation at this stage of a company’s life can be a grey area and I often encounter situations where there is confusion over which method is most appropriate. Since you are not publicly traded, you cannot rely directly on the market. So, what can you do? And how can you come to terms with investors?

Understanding company valuation, either your own or your client’s, is key in your ability to close a good deal. It will affect your investor returns, corporate governance, ability to hire and retain talent, and your ability to raise future rounds.

Ultimately, your valuation will end up being the result of negotiations. It will be what investors are willing to pay for, based on their quantitative and qualitative assessment. Finance is no science. Nonetheless, the more you can demonstrate the value of your business through rigorous, quantified methods, the better prepared you will be. Understanding what your venture could be worth will establish a good basis for discussions, give you credibility, and show investors you are mindful of their concerns. The more operating history your venture has, the more relevant quantitative aspects will be.

Every entrepreneur faces these considerations at one point or another. I know quite well. I am preparing to launch a health and wellness startup. Yet, as former M&A banker, ventures advisor, and financial expert crafting witness testimonies in international arbitration courts, I have had the opportunity to develop some knowledge of business valuation, which I am pleased to share a few bits, with the hope it will benefit you.

Valuation 101 for Pre-Revenue Startups

I will be focusing on later-stage valuation methods in this article. However, before getting into that, I would like to share some advice on how to create a mark for younger, pre-revenue startups.

- Beyond your market potential (TAM/SAM/SOM, trends, drivers), competitive advantage (IP, partnerships, clients, competitors) and burn rate, it will all boil down to the trust investors have in your vision, experience, and ability to execute.

- There are valuation templates floating around, which are not that helpful to founders trying to assess their startup value.

- One approach is the “scorecard method.” It relies on an average valuation of rounds made by angels in a given geography and sector. Since the information is private, it is pretty useless unless you are part of an information-sharing angel network. The key takeaway here is that management and opportunity size matter most.

- The “Berkus method” is, in my humble opinion, an arbitrary and impractical method. It allocates up to $500,000 to 5 criteria, thereby capping any valuation at $2 million.

- Which leaves us with the only really useful approach to founders for pre-revenue valuation: the “venture capital method.” In a nutshell, it derives your post-money value by applying a multiple to future earnings, discounted back to the present by the investor’s hurdle rate. From there you subtract the round raised to get your pre-money valuation.

Now Let’s Dive Into How to Value a Company Pre-IPO

If your venture has operating history, revenues (say $2-3 million), even positive cash flows, you are in a different category. Estimating value for your next funding round or for an exit through M&A or strategic partnership will be a much more quantitative exercise.

Your objective is to measure the earning power and cash generation capability of your company. You have three main valuation techniques at your disposal: (i) comparable company analysis, (ii) precedent transactions analysis, and (iii) discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis.

There is a fourth method, the leveraged buyout (LBO) analysis, which is used to estimate what a private equity (PE) fund would pay for a company. I am not going to review this in detail as it is more applicable to mature businesses with value creation (EBITDA expansion) opportunities.

Before I walk you through specifics, here are some key aspects you should be aware of:

| Valuation | Methodology | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Comparable Public Companies |

|

|

| Comparable Precedent Transactions |

|

|

| Discounted Cash Flow |

|

|

| LBO Analysis |

|

|

1. Comparable Public Companies Analysis

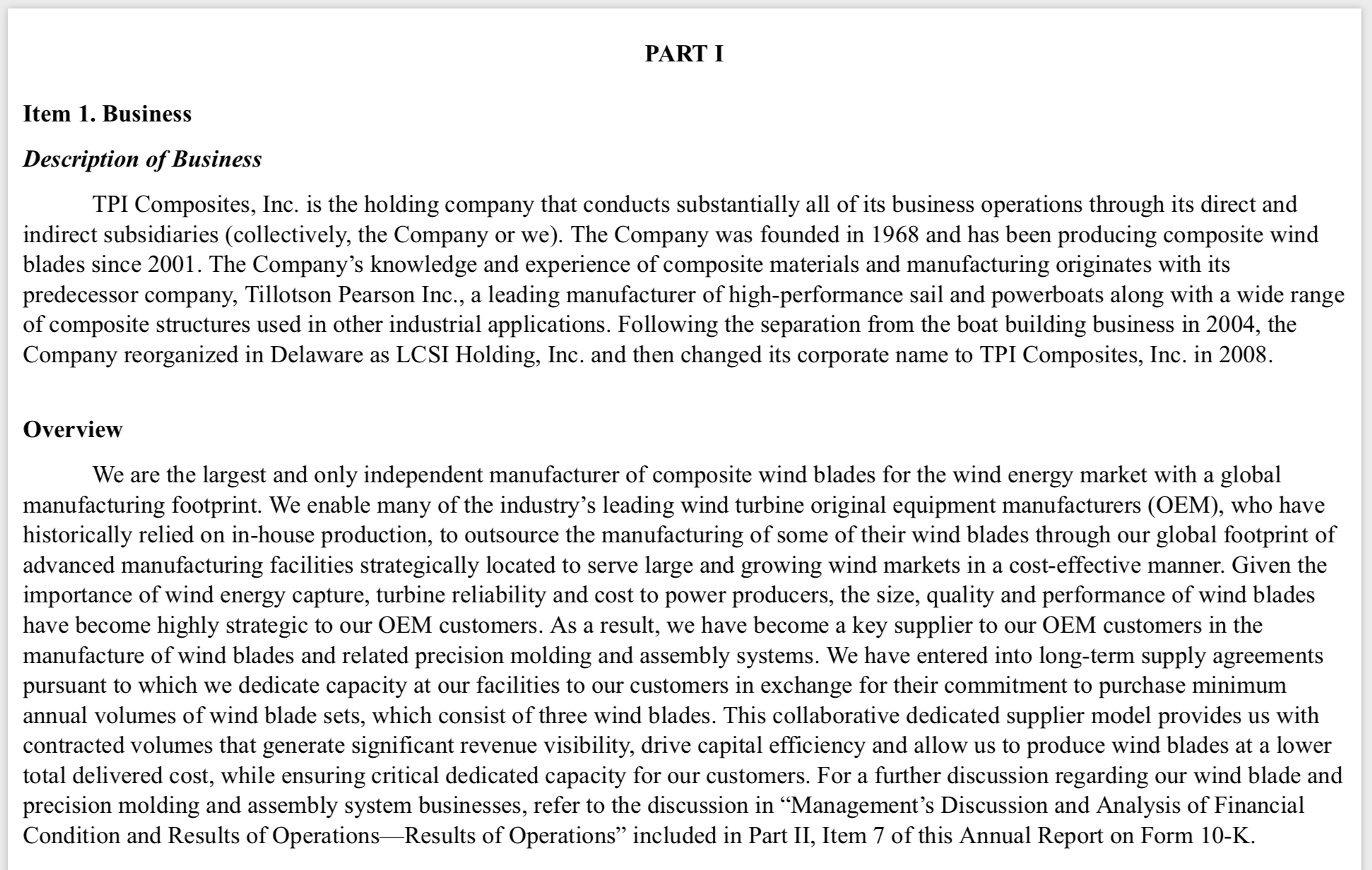

This method assumes that comparable companies tend to be valued with relative consistency by the capital markets. The first thing is to screen for public companies that operate in your sector and have operating models similar to your venture. To refine your screen, read their 10-K (annual SEC filings) if the stock is traded in the US. In particular, read the business description, competition, and management discussion & analysis (MD&A) sections.

I will now illustrate this analysis with the 10-K of TPI Composites, a wind turbine components manufacturer.

Business Description

This provides a general overview of the company in a very neutral manner, which helps to make an informed decision about what it does and how comparable it is to your venture.

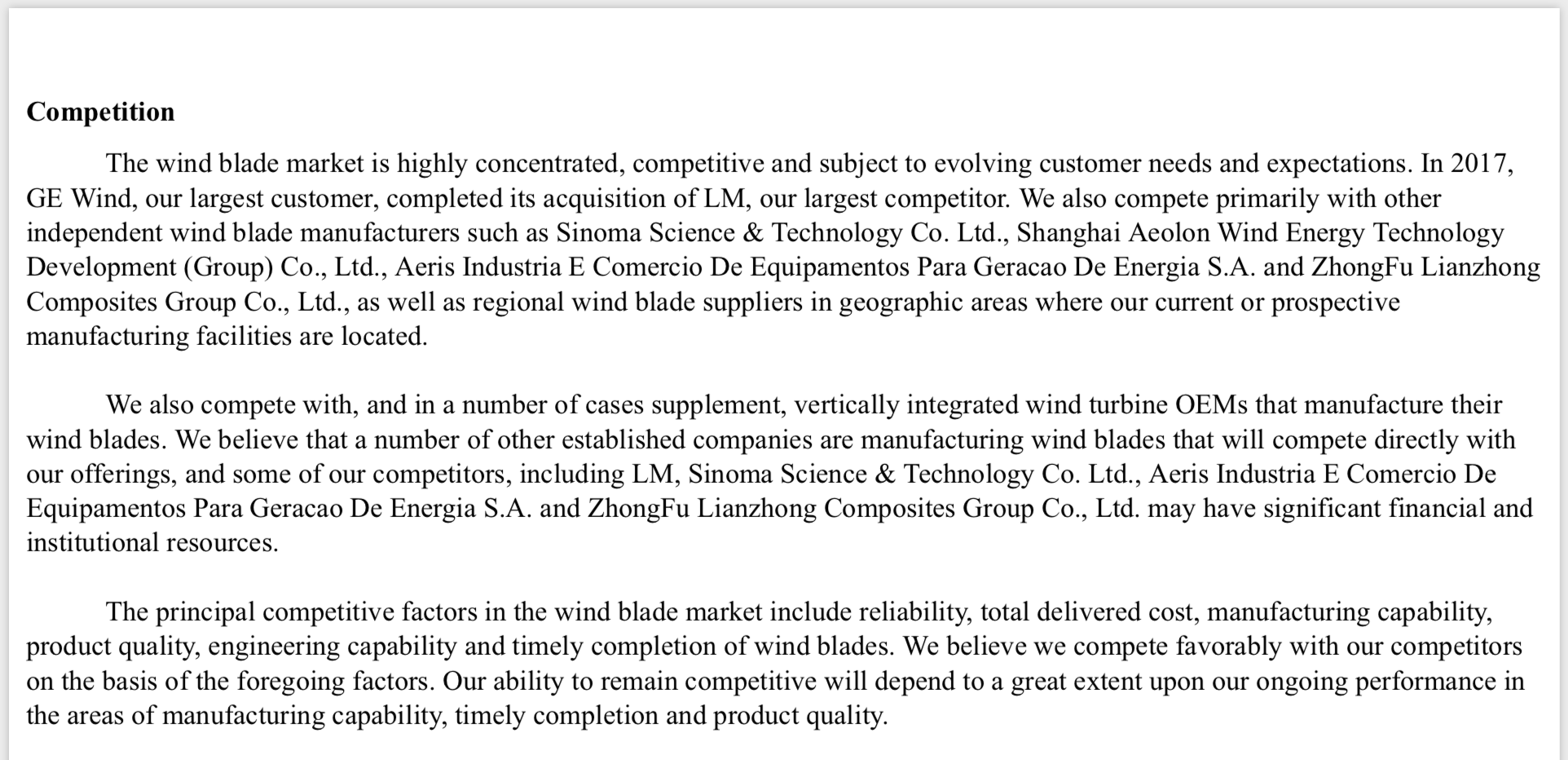

Assessing the competitors that the business perceives it has is also another good sense check for relevance.

Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) Commentary

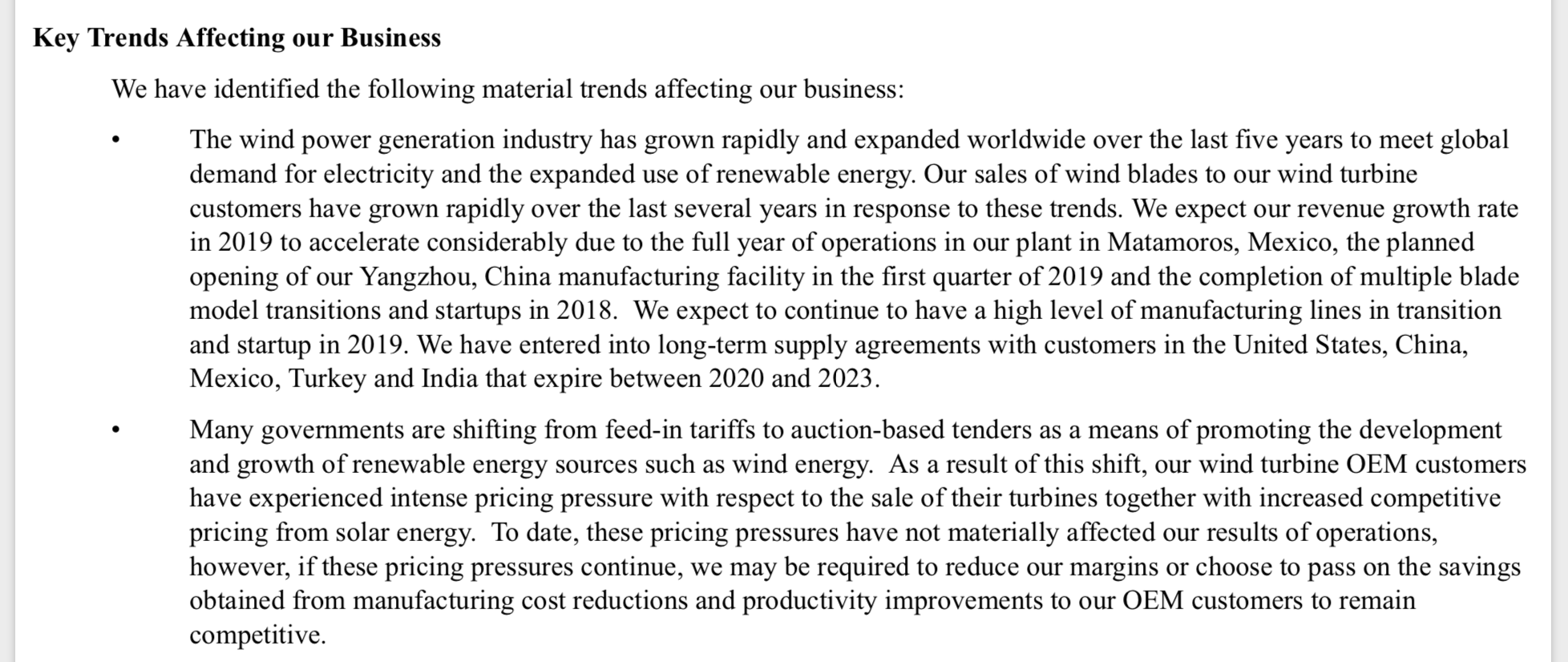

A very pertinent section to look at is the assessment of the key trends currently affecting the business. If this mentions macro themes that your venture is addressing, then it’s another flag that there is a basis for the business to be a valuation proxy.

For example, in the excerpt below, TPI acknowledges the emergent threat of solar energy pricing within its sector of wind energy.

You can also check for any articles and research online. You will have to rely on the most recent filings. Unlike investment bankers, you can’t access databases such as Capital-IQ to get research analysts’ future earnings estimates. Check Yahoo Finance for potential estimates. Once you have selected your comps, the real fun begins. Let’s break down the steps.

Equity Value

Equity value is a more precise representation of the “market capitalization” valuation metric that you see quoted next to public share prices. Unlike market capitalization, equity value counts shareholder loans (i.e. preferred stock) into the equation, in addition to common stock.

Equity value = (diluted common shares outstanding, or DSO) x (price per share). DSO assumes that any options “in the money” are converted into shares and proceeds the company receive from their exercise are used to repurchase shares at the market price.

DSO = (common shares outstanding; found in the latest SEC annual 10-K or quarterly 10-Q, or in foreign filings if non-US) + (options shares equivalent; calculated using the treasury method). Any share equivalents from “in the money” convertible securities should be added too.

Enterprise Value (EV)

Enterprise value is useful for comparing firms with different capital structures. For early-stage venture valuation, it is very useful as a proxy to a public company, due to public companies having more debt capital within their structures.

EV = equity value + net debt. In its simplest form, net debt is = financial liabilities (debt + minority interests) minus the financial assets (cash/equivalents) available to repay liabilities.

Operating Metrics

The metrics you can use to derive multiples are revenues, EBITDA, EBIT, and/or net income. Calculate these metrics in the last twelve months (LTM) for which data is available.

If the most recent filing is 10-K, use that annual figure. If the most recent filing is a 10-Q, you need to calculate the LTM. For example:

LTM revenues = (full-year revenue in latest 10-K) + (revenue for the latest interim period) – (revenue for the corresponding interim period in the previous year) (both in latest 10-Q)

Another key thing is to exclude any non-recurring items from these metrics (e.g. one-time gains/losses, restructuring charges, write-offs, etc.). You can find those in the MD&A, financial statements, and footnotes sections.

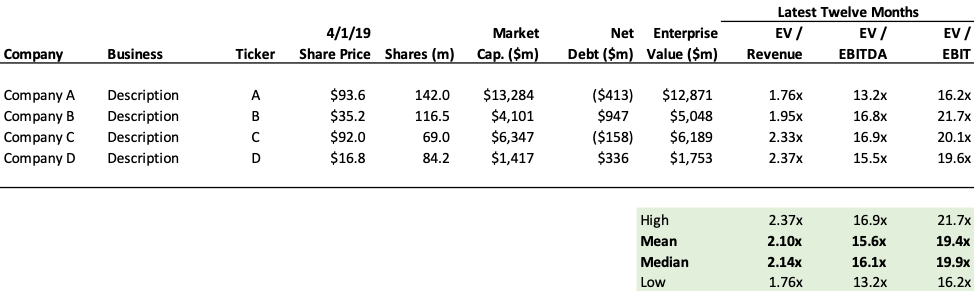

Multiples

At this point, you calculate some multiples for the comp set, for example:

Once calculated, apply them to your company’s metrics and derive its implied value. Whether you apply an average, median, or a tailored range, or whether you exclude outliers from the comp set is where the finesse comes in. Ultimately, your goal is to be as realistic as possible. You also want to include a valuation discount to account for the illiquid nature of your stock and the higher risk profile of a young pre-IPO venture, generally a 20-30% haircut on implied valuation.

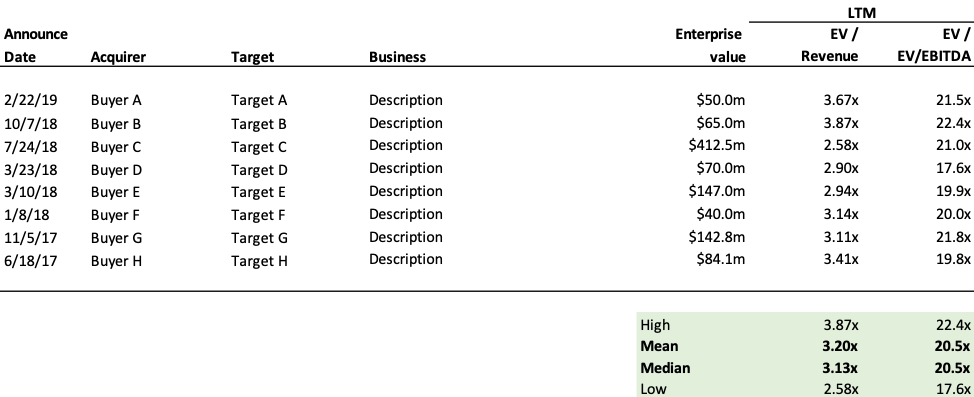

2. Comparable Precedent Transactions Analysis

This analysis will give you an idea of the valuation at which companies such as yours have been acquired in the past. It will help you understand the multiples and control premia paid for companies in your sector. In many instances the targets are private, so you can widen your valuation exercise beyond the publicly traded players.

Another benefit is that it can highlight trends in your industry in terms of consolidations, buyers, investors, and market demand. From there you can get a sense of what an exit might look like for your venture. The value you derive from this analysis will generally be higher than that of comparable company analysis.

The targets you deem most comparable should be studied in greater detail to get a better understanding of the circumstances leading to these valuations. Many factors can influence the price offered for a target including competitive environment among buyers, market conditions at the time, acquirer type (PE constrained by debt terms and target cash flows vs. strategic buyer seeking synergies and EPS accretion), transaction type (e.g. 338(h)(10) election), and governance issues.

The first step is to identify transactions most relevant to your business. My rule of thumb is to look back 5 or 6 years tops. The further back you look, the greater the potential disconnect in terms of market conditions.

The main criteria to consider is the targets’ business and size. As much as possible, pick targets as close to your company size as you can (if none, it’s ok you will just have to account for the gap in your discussions). It is important also to understand the background and context of the deals in order to draw meaningful conclusions.

Here again, you most likely don’t have access to major databases. To identify deals there is no way around it. You’ll have to devote time searching for articles, presentations, and research. You’ll be surprised how much is available online.

Once you have identified relevant transactions, for each target search for the price paid and the most recent operating metrics known at the time of the announcement (revenues, EBITDA).

For public targets, you can find details in merger proxies and tender offer documents (Schedule 14D). For private targets acquired by public companies look at 8-K and 10-K. For other transactions, search for articles and other sources.

Once you have calculated the deal multiples, you can assess which deals are most relevant and apply a benchmark to your venture’s metrics to estimate its value.

3. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

This method is tied directly to your company performance in that the valuation is based primarily on your forecasts, rather than solely market factors.

There is a lot of information out there on how to calculate a discounted cash flow (DCF) and it is a mainstay of finance circular from bachelor degrees onwards. In a nutshell, the valuation involves 4 steps:

- Forecast free cash flows to the firm (FCF)

- Calculate the discount rate of the firm (WACC)

- Estimate terminal value (TV)

- Discount FCF + TV by the WACC to get EV

The following video is particularly useful for gaining an initial understanding of DCF analysis.

a) Find Free Cash Flow

FCF is the cash flow available to capital providers (debt + equity). If positive it can be used for debt service and distribution to shareholders. You generally want to project your FCFs over 5 years. If you budget on a monthly/quarterly basis, consolidate your financials yearly, then expand projections for the outer years.

A simple way to calculate the FCF in a given year is as follows:

EBIT - (tax rate x EBIT) + Depreciation - Capital expenditure - Increase in working capital = FCF to the firm

A couple of suggestions when forecasting:

Revenue

Your growth should converge towards a long-term sustainable rate. If you don’t anticipate a steady growth state by year 5, extend your projections until you think you’ll reach that, but remember the further you project, the less realistic it will be. You’re already throwing spaghetti on the wall forecasting five years in the future anyway.

Margins

Project what you expect (must be defensible) rather than what has been.

Depreciation and CapEx

Unless you have a capital-intensive business with different asset types, depreciation is often projected as a % of sales. Keep in mind the relationship between CapEx and depreciation. CapEx should converge toward depreciation as a % of sales as you reach a steady state.

Working capital

If you can, project each component separately (e.g. inventory, receivables, payables), otherwise, you can use a % of sales.

b) Uncover the Discount Rate

Your WACC should reflect the after-tax return expected by the capital providers (lenders and investors). This blended return is used to discount your FCFs and TV to their present value. The WACC includes the cost of equity (see CAPM method) and the cost of debt. To calculate the cost of equity, you must estimate the Beta for your company. As you do, use the comps you picked for your comparable company analysis and their average capital structures rather than the capital structure of your company.

c) Deciding on a Terminal Value

The TV is a proxy for your business value beyond the projected period. Depending on the situation, TV can represent ¾ or more of the EV in a DCF. Consequently, the assumptions behind its calculation must be well thought through. TV is calculated with two methods:

- Exit multiple: applying a multiple to your EBITDA at the end of the forecast; use the LTM multiple calculated in your comparable companies’ analysis

- Perpetuity growth: applying a perpetuity growth rate, assuming your company will generate FCFs growing steadily forever.

The most important thing is to cross-check the results between the two approaches. Calculate the implied growth rate derived from the exit multiple method and the implied multiple derived from the perpetuity growth method. They must be aligned.

d) Getting to the Final Value

You can now calculate your EV by discounting FCFs and TV with WACC and adding them. Note that the DCF analysis will generally give the highest valuation of all methods. Be prepared; investors will comb through your plan and take a cut at your assumptions. Professor Damodaran at NYU, a reference among the expert witnesses I worked with in international arbitration courts, offers many templates you can play with.

Stay Alert and Flexible Around Updating Your Valuation

Depending on your industry, or how fast you’re growing for example (+50% or +1,000%/year?), you may have to adjust your valuation. These things come with experience, but let me give an example.

Applying a valuation multiple to sales in year N vs. N+1 will lead to a massive difference if you are growing at a fast click. It is good to consider a run rate revenue number in this case (annualize your last 3 months to get to full-year equivalent for an LTM valuation). Similarly, adjust your LTM EBITDA if you anticipate a notable change in margin next year (say marketing spend will change substantially).

How Does Valuation Impact Investors?

Valuation affects investors’ ownership stake and return. The higher the valuation, the lower the investor share and the lower their rate of return. Valuation will affect also investors’ appetite depending on your plan if say you anticipate needing additional capital in the future to fuel your growth. Growing sales, market penetration, and growing cash flow will increase your company value and enable you to raise future rounds at higher valuations. From the investor standpoint, this is good, however, given the dilutive effect of issuing more shares in future rounds, your current investors won’t capture the full valuation increase. This is known as the divergence effect. As a result, investors will be sensitive to the valuation at which they enter, since an overly high pre-money valuation could have major adverse consequences if you miss your targets and end-up having to raise funds below your current valuation.

A second key aspect is to profile which investors you are targeting and why. Depending on your business, stage, and market, you could approach different types of investors (friends/family, HNW/family offices, venture capital funds, impact funds). Each has different return expectations, investment horizons, and governance requirements. For example, venture capitalists may expect an ROI of 10x over 4-5 years, while impact investors committed to improving social or environmental outcomes might target returns in the mid-teens over a longer investment period of 8-10 years.

Getting A Deal Over the Line

Beyond your team, business plan, and market potential, your corporate governance, funding structure, and investors’ rights (e.g. tag-along, drag-along, ROFR, ROFO) will affect the investment value. If there is a disconnect in perceived value between you and your investors, you can do a few things to bridge the gap. You may issue preferred stocks with liquidation preferences, which give investors some protection and help increase their return. You could also offer investors warrants to buy additional shares in the future at the same price. Another option is to issue a convertible note, which offers more seniority and increases the investor’s future valuation and stake, as a result of the interests accruing pre-conversion. You can, instead of a note, issue a non-interest bearing SAFE if you are at the seed stage. Both instruments can carry a discount, a cap, and most-favored nation. On the governance side, you can offer board representation, agree to protective provisions such as defining the scope of decisions requiring a quorum, or grant investors veto rights.

Ultimately, it will boil down to how interested the investors are in your story and how motivated you are to partnering up. As the market and economy enter a more uncertain phase, now is an excellent time to explore your company’s value and see how to best navigate fundraising or exit opportunities. Remember to be structured in your analysis and best of luck.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is the difference between equity value and market capitalization?

Equity value is a more precise representation of the market capitalization valuation metric seen quoted alongside public share prices. Unlike market capitalization, equity value counts shareholder loans (i.e. preferred stock) into the equation, in addition to common stock.

Bertrand Deleuse

New York, NY, United States

Member since January 16, 2019

About the author

Bertrand is a finance veteran and startup advisor, with a 20-year track record advising 50+ clients on $16 billion of deals.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT