A Guide to Managing Foreign Exchange Risk

This useful guide by Toptal Finance Expert Paul Ainsworth draws on 30+ years of experience as a CFO of large multinational companies to lay out the menu of options companies face in order to deal with foreign exchange exposure and manage risk effectively.

This useful guide by Toptal Finance Expert Paul Ainsworth draws on 30+ years of experience as a CFO of large multinational companies to lay out the menu of options companies face in order to deal with foreign exchange exposure and manage risk effectively.

An international CFO with experience at large multinationals, Paul has led simplification projects across geographically disparate teams.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Exchange rate fluctuation is an everyday occurrence. From the holidaymaker planning a trip abroad and wondering when and how to obtain local currency to the multinational organization buying and selling in multiple countries, the impact of getting it wrong can be substantial. That’s why foreign exchange risk management (or forex risk management) is so important.

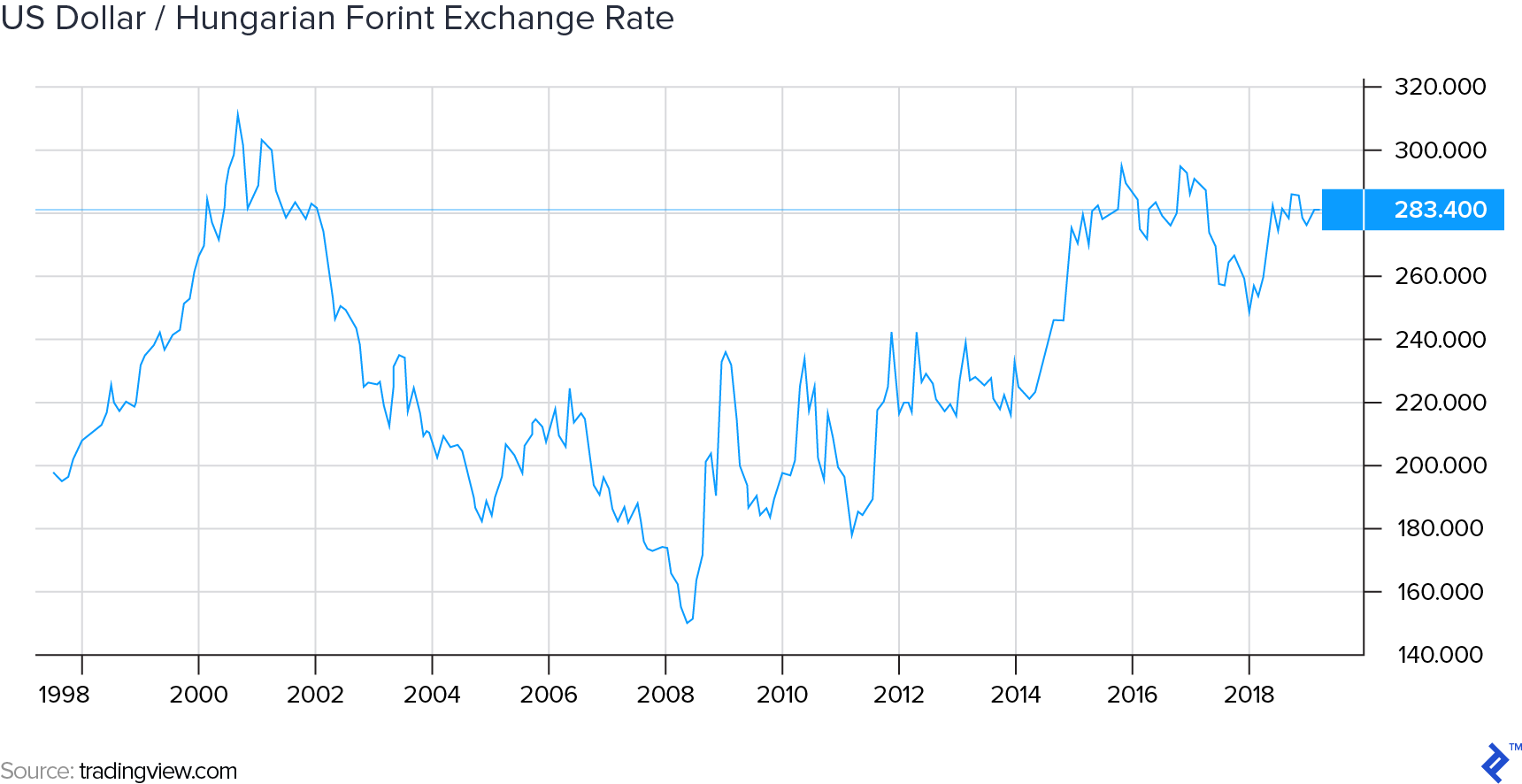

During my first overseas assignment in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I came to work in Hungary, a country experiencing a huge transformation following the regime change of 1989, but one in which foreign investors were keen to invest. The transition to a market economy generated significant currency volatility, as the chart below highlights. The Hungarian Forint (HUF) lost 50% of its value against the USD between 1998 and 2001 and then regained it all by the end of 2004 (with significant fluctuations along the way).

With foreign currency trading in the HUF in its infancy and therefore hedging prohibitively expensive, it was during this time that I learned firsthand the impact foreign currency volatility can have on the P&L. In the reporting currency of USD, results could jump from profit to loss purely on the basis of exchange movements and it introduced me to the importance of understanding foreign currency and currency risk management.

The lessons I learned have proved invaluable throughout my 30+ year career as a CFO of large, multinational companies. However, I see many instances still today of companies that fail to properly mitigate foreign exchange risk and suffer the consequences as a result. For this reason, I thought it useful to create a simple guide to those interested in learning about the ways one can counter currency risk, and the menu of options companies face, sharing a few of my personal experiences along the way. I hope you find it useful.

Types of Foreign Exchange Risk

Fundamentally, there are three types of foreign exchange exposure companies face: transaction exposure, translation exposure, and economic (or operating) exposure. We’ll run through these in greater detail below.

Transaction Exposure

This is the simplest kind of foreign currency exposure and, as the name itself suggests, arises due to an actual business transaction taking place in foreign currency. The exposure occurs, for example, due to the time difference between an entitlement to receive cash from a customer and the actual physical receipt of the cash or, in the case of a payable, the time between placing the purchase order and settlement of the invoice.

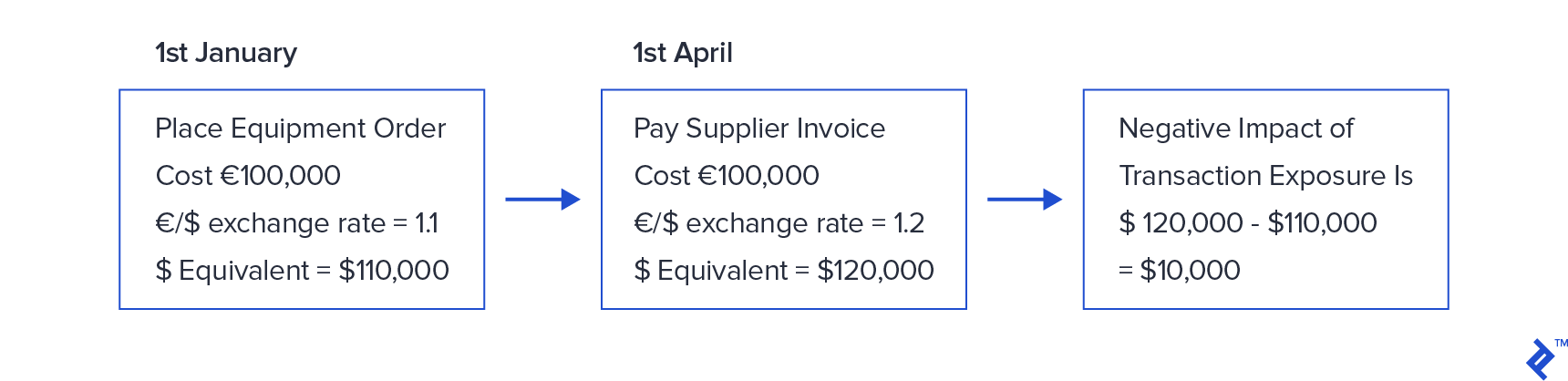

Example: A US company wishes to purchase a piece of equipment and, after receiving quotes from several suppliers (both domestic and foreign), has chosen to buy in Euro from a company in Germany. The equipment costs €100,000 and at the time of placing the order the €/$ exchange rate is 1.1, meaning that cost to the company in USD is $110,000. Three months later, when the invoice is due for payment, the $ has weakened and the €/$ exchange rate is now 1.2. The cost to the company to settle the same €100,000 payable is now $120,000. Transaction exposure has resulted in an additional unexpected cost to the company of $10,000 and may mean the company could have purchased the equipment at a lower price from one of the alternative suppliers.

Translation Exposure

Sometimes known as exchange rate exposure, this is the translation or conversion of the financial statements (such as P&L or balance sheet) of a foreign subsidiary from its local currency into the reporting currency of the parent. This arises because the parent company has reporting obligations to shareholders and regulators which require it to provide a consolidated set of accounts in its reporting currency for all its subsidiaries.

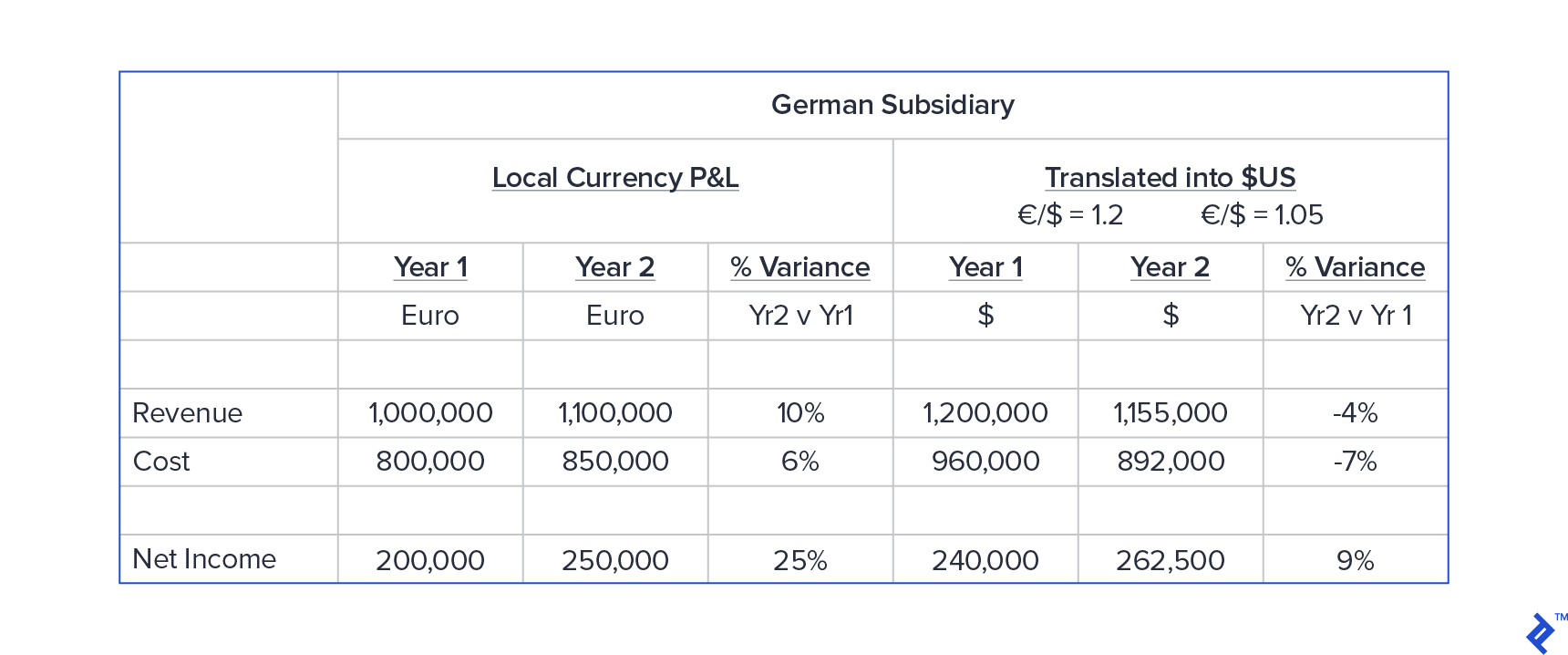

Following on from the above example, let’s assume that the US company decides to set up a subsidiary in Germany to manufacture equipment. The subsidiary will report its financials in Euros and the US parent will translate those statements into USD.

The example below shows the financial performance of the subsidiary in its local currency of Euro. Between years one and two, it has grown revenue by 10% and achieved some productivity to keep cost increases to only 6%. This results in an impressive 25% increase in net income.

However, because of the impact of exchange rate movements, the financial performance looks very different in the parent company’s reporting currency of USD. Over the two year period, in this example, the dollar has strengthened and the €/$ exchange rate has dropped from an average of 1.2 in Year 1 to 1.05 in Year 2. The financial performance in USD looks a lot worse. Revenue is reported as falling by 4% and net income, while still showing growth, is only up by 9% rather than 25%.

The opposite effect can of course occur, which is why, when reporting financial performance, you will often hear companies quote both a “reported” and “local currency” number for some of the key metrics such as revenue.

Economic (or Operating) Exposure

This final type of foreign exchange exposure is caused by the effect of unexpected and unavoidable currency fluctuations on a company’s future cash flows and market value, and is long-term in nature. This type of exposure can impact longer-term strategic decisions such as where to invest in manufacturing capacity.

In my Hungarian experience referenced at the beginning, the company I worked for transferred large amounts of capacity from the US to Hungary in the early part of the 2000s to take advantage of lower manufacturing cost. It was more economic to manufacture in Hungary and then ship product back to the US However, the Hungarian Forint then strengthened significantly over the following decade and wiped out many of the predicted cost benefits. Exchange rate changes can greatly affect a company’s competitive position, even if it does not operate or sell overseas. For example, a US furniture manufacturer who only sells locally still has to contend with imports from Asia and Europe, which may get cheaper and thus more competitive if the dollar strengthens markedly.

How to Mitigate Foreign Exchange Risk

The first question to ask is whether to bother attempting to mitigate the risk at all. It may be that a company accepts the risk of currency movement as a cost of doing business and is prepared to deal with the potential earnings volatility. The company may have sufficiently high profit margins that provide a buffer against exchange rate volatility, or they have such a strong brand/competitive position that they are able to raise prices to offset adverse movements. Additionally, the company may be trading with a country whose currency has a peg to the USD, although the list of countries with a formal peg is small and not that significant in terms of volume of trade (with the exception of Saudi Arabia which has had a peg in place with the USD since 2003).

For those companies that choose to actively manage foreign exchange risk, the tools available range from the very simple and low cost to the more complex and expensive.

Transact in Your Own Currency

Companies in a strong competitive position selling a product or service with an exceptional brand may be able to transact in only one currency. For example, a US company may be able to insist on invoicing and payment in USD even when operating abroad. This passes the exchange risk onto the local customer/supplier.

In practice, this may be difficult since there are certain costs that must be paid in local currency, such as taxes and salaries, but it may be possible for a company whose business is primarily done online.

Build Protection into Your Commercial Relationships/Contracts

Many companies managing large infrastructure projects, such as those in the oil and gas, energy, or mining industries are often subject to long-term contracts which may involve a significant foreign currency element. These contracts may last many years and the exchange rates at the time of agreeing to the contract and setting the price may then fluctuate and jeopardize profitability. It may be possible to build foreign exchange clauses into the contract that allow revenue to be recouped in the event that exchange rates deviate more than an agreed amount. This obviously then passes any foreign exchange risk onto the customer/supplier and will need to be negotiated just like any other contract clause.

In my experience, these can be a very effective way of protecting against foreign exchange volatility but does require the legal language in the contract to be strong and the indices against which the exchange rates are measured to be stated very clearly. These clauses also require that a regular review rigor be implemented by the finance and commercial teams to ensure that once an exchange rate clause is triggered the necessary process to recoup the loss is actioned.

Finally, these clauses can lead to tough commercial discussions with the customers if they get triggered and often I have seen companies choose not to enforce to protect a client relationship, especially if the timing coincides with the start of negotiations on a new contract or an extension.

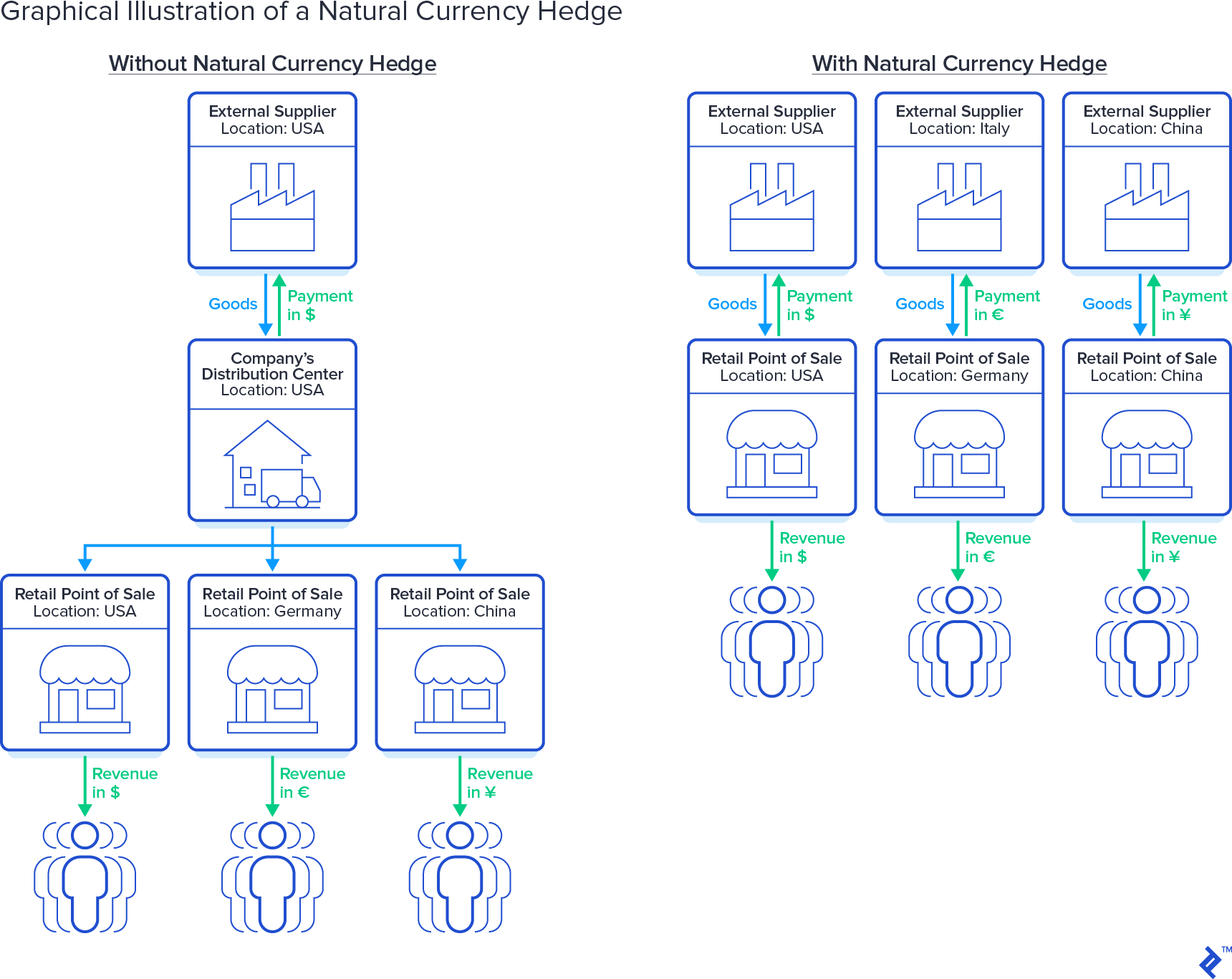

Natural Foreign Exchange Hedging

A natural foreign exchange hedge occurs when a company is able to match revenues and costs in foreign currencies such that the net exposure is minimized or eliminated. For example, a US company operating in Europe and generating Euro income may look to source product from Europe for supply into its domestic US business in order to utilize these Euros. This is an example which does somewhat simplify the supply chain of most businesses, but I have seen this effectively used when a company has entities across many countries.

However, it does place an extra burden on the finance team and the CFO because, in order to track net exposures, it requires a multiple currency P&L and balance sheet to be managed alongside the traditional books of account.

Hedging Arrangements via Financial Instruments

The most complicated, albeit probably well-known way of hedging foreign currency risk is through the use of hedging arrangements via financial instruments. The two primary methods of hedging are through a forward contract or a currency option.

-

Forward exchange contracts. A forward exchange contract is an agreement under which a business agrees to buy or sell a certain amount of foreign currency on a specific future date. By entering into this contract with a third party (typically a bank or other financial institution), the business can protect itself from subsequent fluctuations in a foreign currency’s exchange rate.

The intent of this contract is to hedge a foreign exchange position in order to avoid a loss on a specific transaction. In the equipment transaction example from earlier, the company can purchase a foreign currency hedge that locks in the €/$ rate of 1.1 at the time of sale. The cost of the hedge includes a transaction fee payable to the third party and an adjustment to reflect the interest rate differential between the two currencies. Hedges can generally be taken for up to 12 months in advance although some of the major currency pairs can be hedged over a longer timeframe.

I have used forward contracts many times in my career and they can be very effective, but only if the company has solid working capital processes in place. The benefits of the protection only materialize if transactions (customer receipts or supplier payments) take place on the expected date. There needs to be close alignment between the creasury function and the cash collection/accounts payable teams to ensure this happens.

-

Currency options. Currency options give the company the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a currency at a specific rate on or before a specific date. They are similar to forward contracts, but the company is not forced to complete the transaction when the contract’s expiration date arrives. Therefore, if the option’s exchange rate is more favorable than the current spot market rate, the investor would exercise the option and benefit from the contract. If the spot market rate was less favorable, then the investor would let the option expire worthless and conduct the foreign exchange trade in the spot market. This flexibility is not free and the company will need to pay an option premium.

In the equipment example above, let’s assume the company wishes to take out an option instead of a forward contract and that the option premium is $5,000.

In the scenario that the USD weakens from €/$ 1.1 to 1.2, then the company would exercise the option and avoid the exchange loss of $10,000 (although would still suffer the option cost of $5,000).

In the scenario that the USD strengthens from €/$ 1.1 to 0.95, then the company would let the option expire and bank the exchange gain of $15,000, leaving a net gain of $10,000 after accounting for the cost of the option.

In reality, the cost of the option premium will depend on the currencies being traded and the length of time the option is taken out for. Many companies deem the cost too prohibitive.

Don’t Let Foreign Exchange Risk Hurt Your Company

During my career, I have worked in companies that have operated very rigorous hedging models and also companies that have hedged very little, or not at all. The decision often boils down to the risk appetite of the company and the industry in which they operate, however, I have learned a few things along the way.

In companies that do hedge, it is very important to have a strong financial forecasting process and a solid understanding of the foreign exchange exposure. Overhedging because a financial forecast was too optimistic can be an expensive mistake. In addition, having a personal view on currency movements and taking a position based on anticipated currency fluctuations starts to cross a thin line that separates foreign exchange risk management and speculation.

Even in companies that decide not to hedge, I would still argue it is necessary to understand the impact of currency movements on a foreign entity’s books so that the underlying financial performance can be analyzed. As we saw in the example above, with the German subsidiary, exchange rate movements can have a significant impact on the reported earnings. If exchange rate movements mask the performance of the entity then this can lead to poor decision-making.

For companies choosing a financial instrument to hedge their exposure, remember that not all banks/institutions provide the same service. A good hedging provider should carry out a thorough review of the company to assess exposure, help to set up a formal policy, and provide a bundled package of services that address every step in the process. Here are a few criteria to consider:

- Will you have direct access to experienced traders and are they on hand to provide a consultative service as well as execution?

- Does the provider have experience operating in your particular industry?

- How quickly will the provider obtain live executable quotes and do they trade in all liquid currencies?

- Does the provider have sufficient resources to correct settlement problems and ensure that your contract execution happens in full on the required date?

- Will the provider provide regular reports on transaction history and outstanding trades?

Ultimately, foreign exchange is just one of many risks involved for a company operating outside its domestic market. A company must consider how to deal with that risk. Hoping for the best and relying on stable financial markets rarely works. Just ask the holidaymaker faced with incurring 20% more than expected for their beer/coffee/food because of an unexpected exchange rate movement.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

How does a currency hedge work?

The easiest way to think about a currency hedge is like a form of insurance. It is an instrument that helps protect against financial loss arising from movements in exchange rates. It is an agreement to buy or sell currency at a predetermined exchange rate at a specific date in the future.

How do you mitigate foreign exchange risk?

A company can avoid forex exposure by only operating in its domestic market and transacting in local currency. Otherwise, it must attempt to match foreign currency receipts with outflows (a natural hedge), build protection into commercial contracts, or take out a financial instrument such as a forward contract.

What are the types of foreign exchange exposure?

Transactional exposure arises from sales/purchases denominated in foreign currency. Translational exposure arises from the translation of account balances recorded in foreign currencies into the reporting currency. Economic exposure arises when exchange rate changes impact long-term competitive dynamics.

Paul Ainsworth

Budapest, Hungary

Member since November 9, 2018

About the author

An international CFO with experience at large multinationals, Paul has led simplification projects across geographically disparate teams.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT