How Is the International Money Transfer Market Evolving?

With the global workforce becoming increasingly mobile, international money transfers (“remittances”) have equally grown in prominence, passing the $530 billion a year mark in 2016.

Fees for transfers are at an all-time low, thanks to pressure from bodies such as the UN, which is providing consumers with more value. But how are transfer companies responding to this pressure and what steps are they taking to differentiate themselves from the rest of the pack?

With the global workforce becoming increasingly mobile, international money transfers (“remittances”) have equally grown in prominence, passing the $530 billion a year mark in 2016.

Fees for transfers are at an all-time low, thanks to pressure from bodies such as the UN, which is providing consumers with more value. But how are transfer companies responding to this pressure and what steps are they taking to differentiate themselves from the rest of the pack?

Mauro has led origination efforts for over $150m of private placement bond deals and built up finance teams for a range of startups.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Executive Summary

International money transfer is a large and competitive industry

- The market of international money transfer ("remittance market") has been growing considerably at a CAGR of 10.4% since 2000. $530 billion is transferred each year.

- Pressure from the G20 and UN to lower costs for senders has resulted in fees for transfers declining year-on-year since 2008. It now costs on average 7.21% to send money abroad.

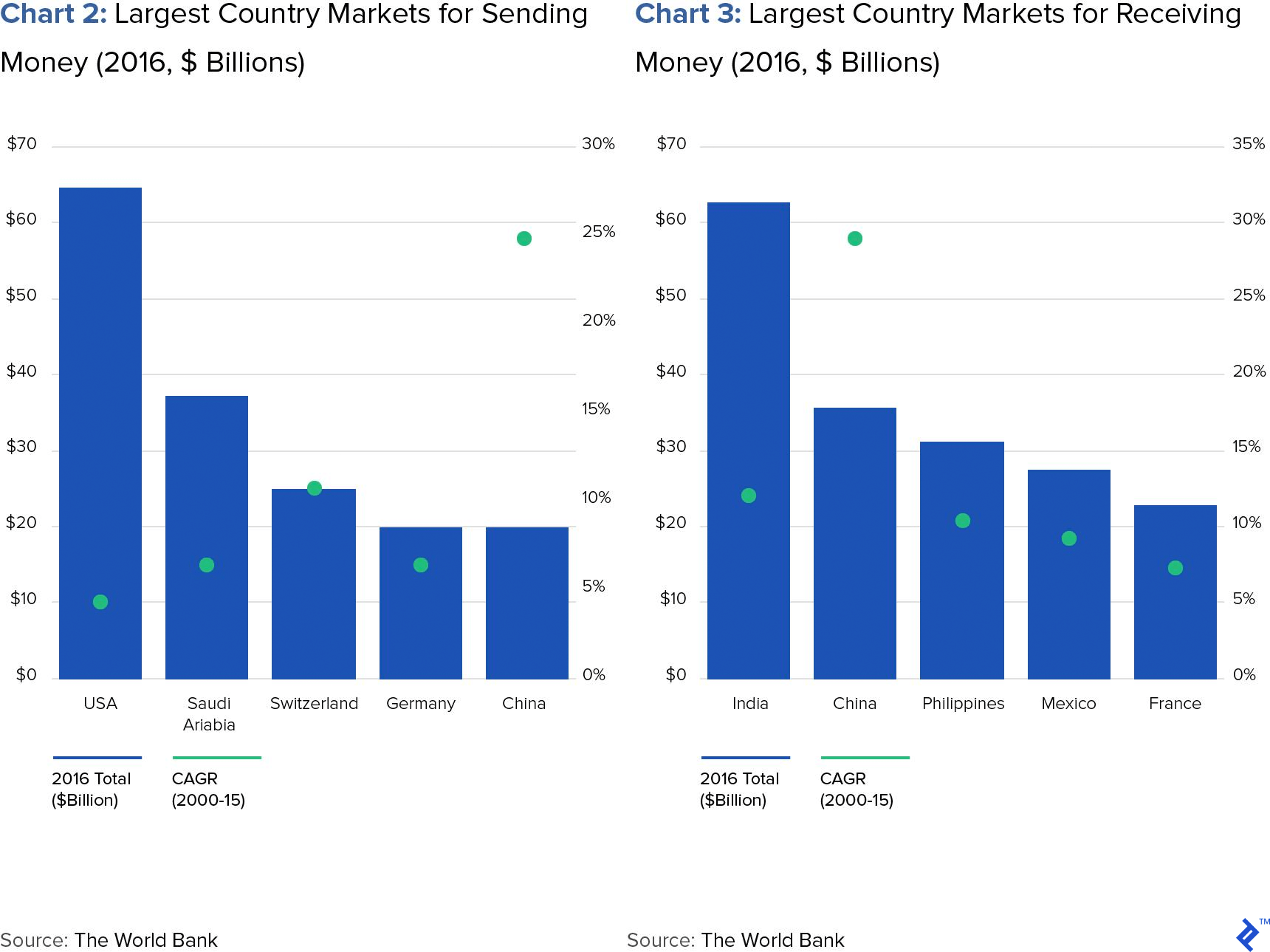

- The USA is the country that sends the most money, India receives the most money and China has the most even balance between sending and receiving.

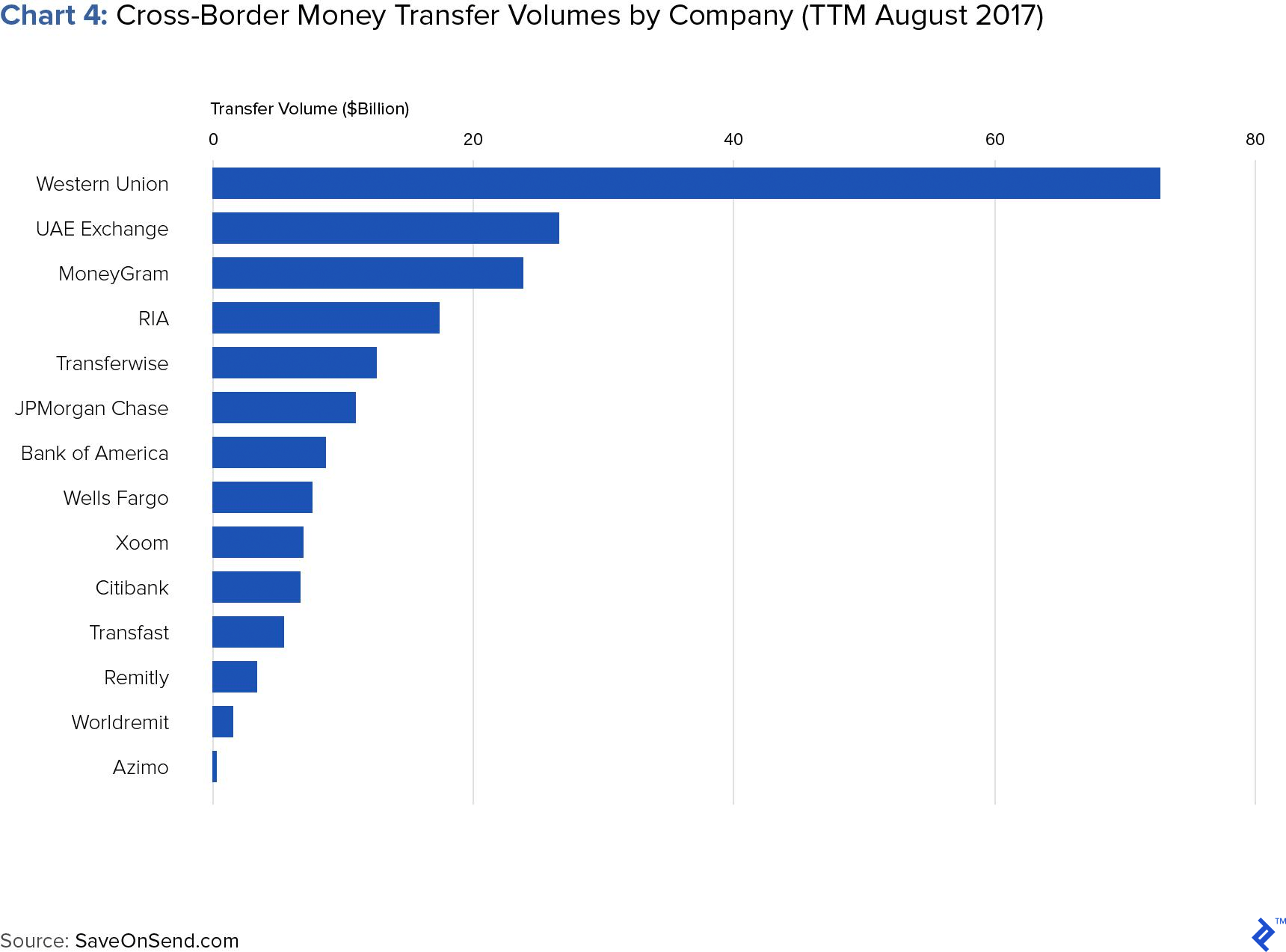

- Western Union processes over $70 billion in payments every year, more than double that of its nearest competitor, UAE Exchange. The highest volume from a Fintech "newcomer" is from 6-year old Transferwise, which is ranked 5th in the world.

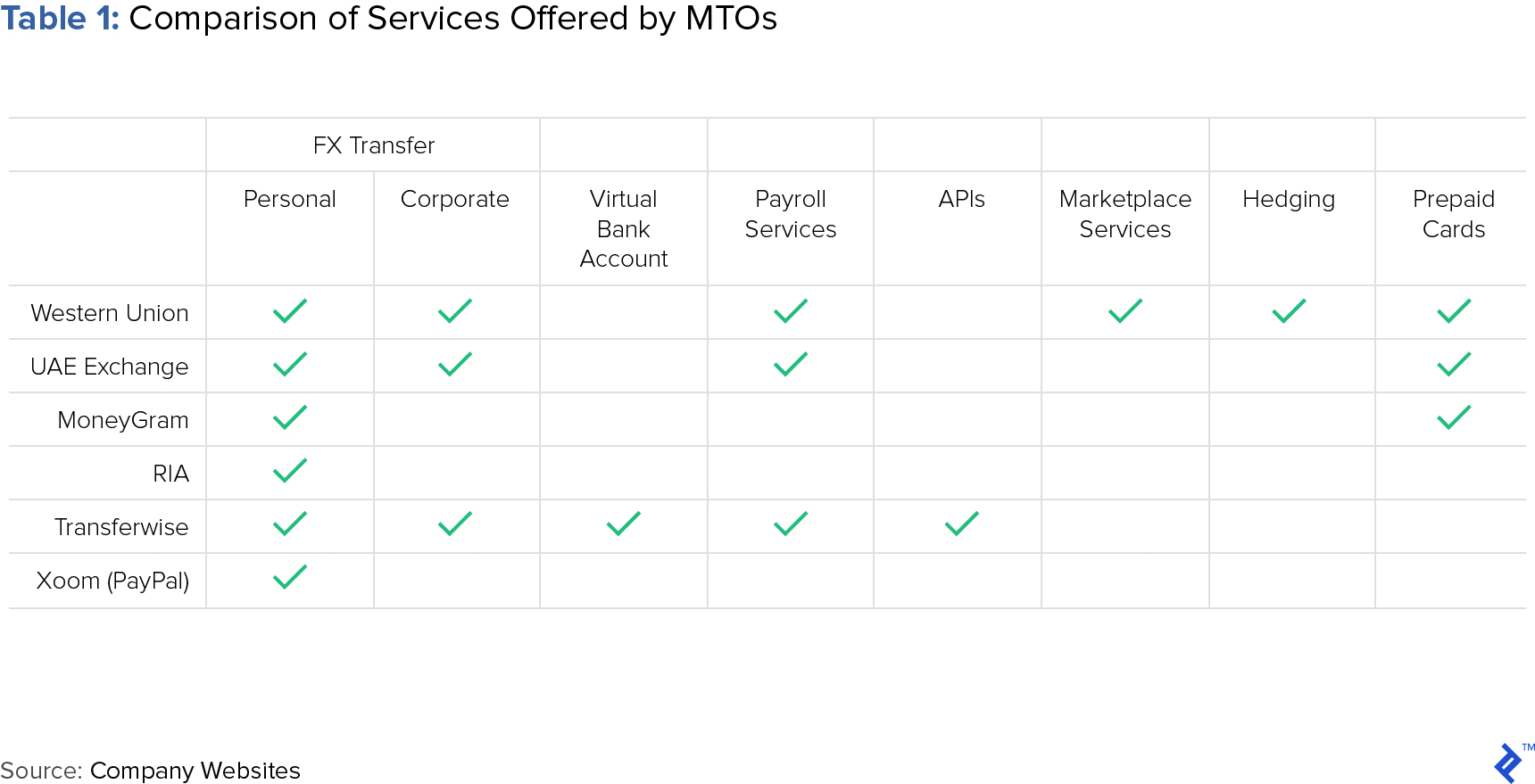

- With fees falling, MTOs are now differentiating themselves from their competitors by offering new services to increase customer loyalty, such as payroll services, virtual bank accounts, and prepaid debit cards.

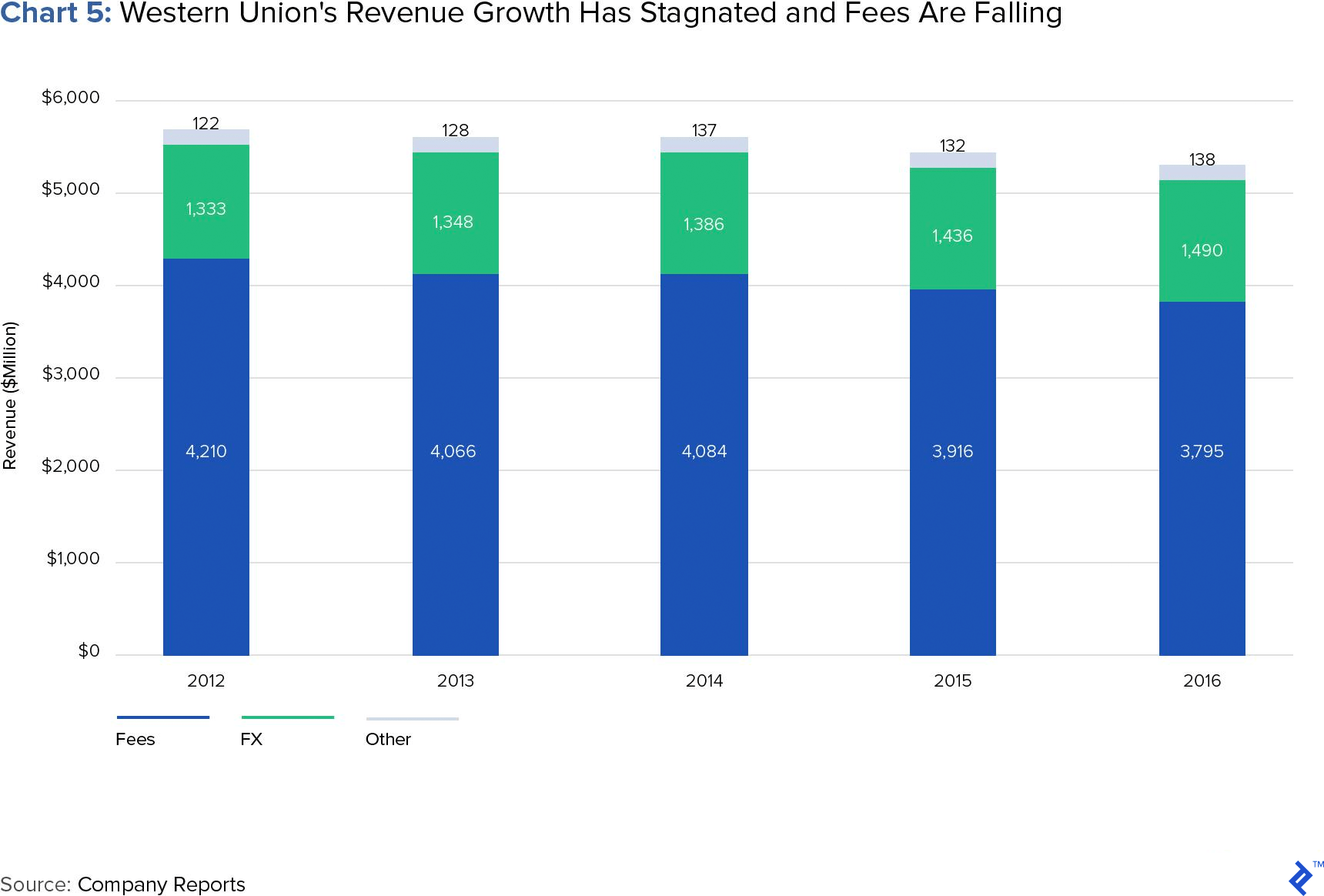

Western Union has some innovative value-added services, but its revenue growth is paralyzed

- The move to cut fees has stalled Western Union's revenue growth over the past five years. It has tried to compensate fee compression by increasing foreign exchange ("FX") revenue. in 2016 fees and FX revenue constituted 70% and 27% respectively of its total revenue

- Trying to increase FX charges is a potentially dangerous move to make, as customers are more cognizant to the real cost of FX through transparency efforts by competitors.

- To respond to the increased competition, Western Union is focusing more on small businesses, offering innovative tools such as hedging and marketplaces for customers to connect.

- Have 500,000 branches in its network affects its ability to respond to cheaper electronic transfer services. Western Union runs the risk of being disrupted significantly, in a similar vein to how Blockbuster Video was by online video-on-demand services.

Transferwise works on thin margins, but is building scale and has ambitious plans

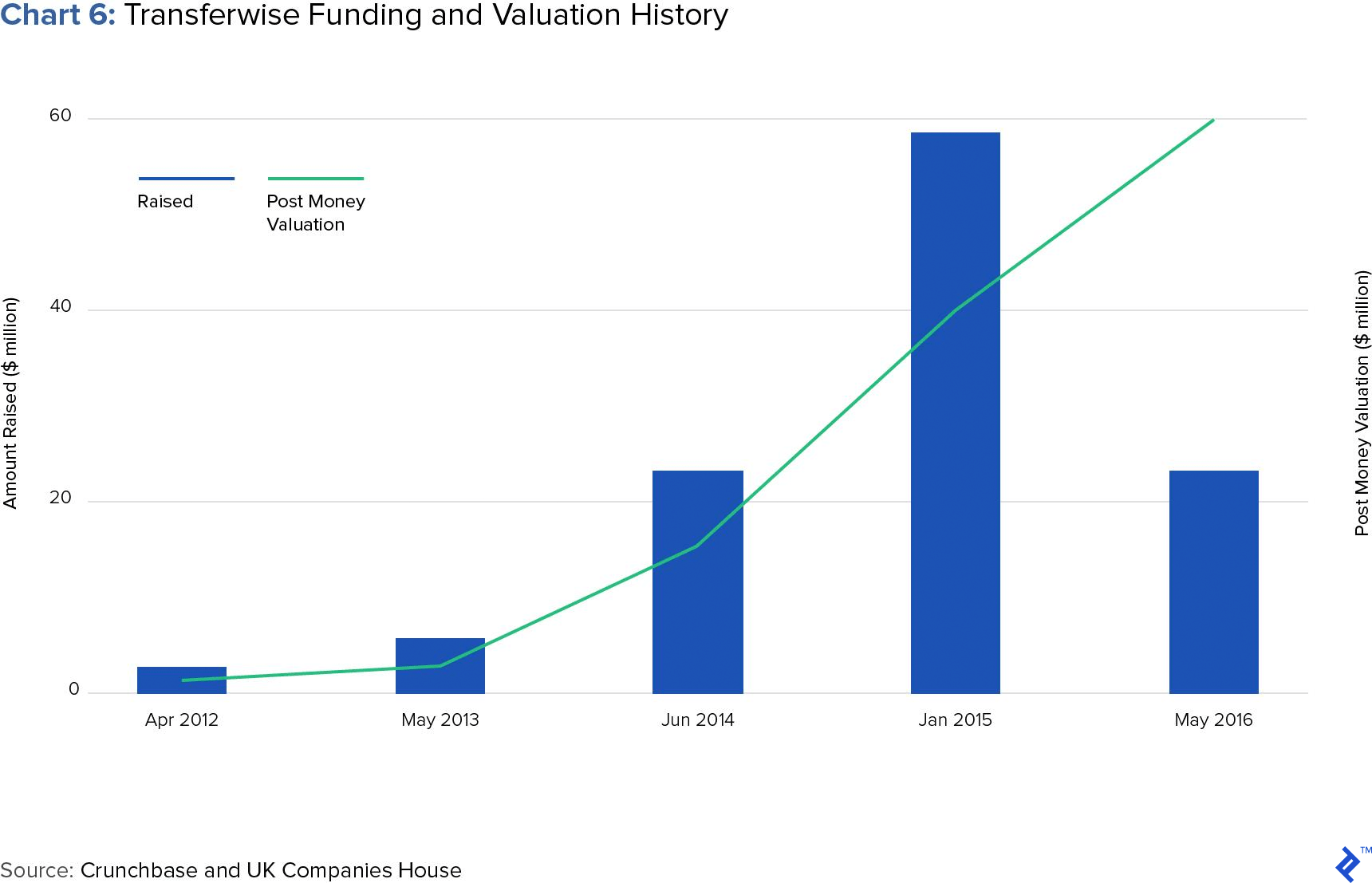

- Formed in Estonia in 2011, six years on, Transferwise is predicted to reach a valuation of $1.6 billion in 2017. It now has a profitable business model and significant market share (10%) in its primary market, the UK.

- It offers customers very competitive fee prices (0.5% for EUR to USD) and famously does not pass on any FX costs, which it attempts to mitigate through bypassing banks with its peer-to-peer exchange model.

- Reaching a break-even point with such attractive customer pricing suggests that Transferwise has significant scale, in terms of number of transactions and an efficient technological operational back-end.

- Its moves into transactional banking via its "Borderless Account" offering show that it plans on transitioning more into the banking space, to capture more transactions from customers and maintain passive account balances.

Xoom's focused approach appealed to investors

- Xoom IPOed in 2013 and was bought by PayPal for $890 million in 2015. Alongside its acquirer, it remains one of the most significant exits for investors in the money transfer space.

- It offers a very straightforward business model of only sending money for US-based customers, albeit with a wide range of options for inbound remittances (cash pickup, mobile topup, and electronic transfer).

- PayPal's interest in Xoom came due to its vast network of physical affiliate agents around the world, which augmented PayPal's strength in internet payments and processing.

- By focusing on its core strength and not stretching itself across many different business functions, Xoom was able to perfect its business model and present itself as an attractive investment for both its IPO investors and PayPal.

There are three sources of intangible value in an MTO

- With international money transfer displaying characteristics of a commodity market, its players need to differentiate themselves from the competition with more value-added services to retain customer loyalty.

- The race to the bottom in terms of fees charged and FX spread taken means that, to succeed and grow in value, they need to show strength across these three categories:

- Brand value: Loyalty and trust from customers due to being a transparent and reliable service.

- Depth of agents/banks in its affiliate network: Offering more options to senders and receivers increases the utility offered to them and makes them stickier.

- Proprietary technology: Using technology to lower customers' costs and win business through making transfers faster and more reliably.

How Is the International Money Transfer Market Evolving?

Sending money abroad has traditionally been an arduous and expensive task, exemplified by never-ending chains of middlemen, manual paperwork, and hidden charges. Fortunately, developments in the money transfer industry over the past couple of years mean that individuals and even small-to-mid-sized businesses can now enjoy faster, cheaper, and value-added foreign money transfer services from remittance companies. These are all benefits which larger corporates, banks, and governments have traditionally held through their direct access to the institutional foreign exchange market, which exchanges $4.8 trillion of transactions each day.

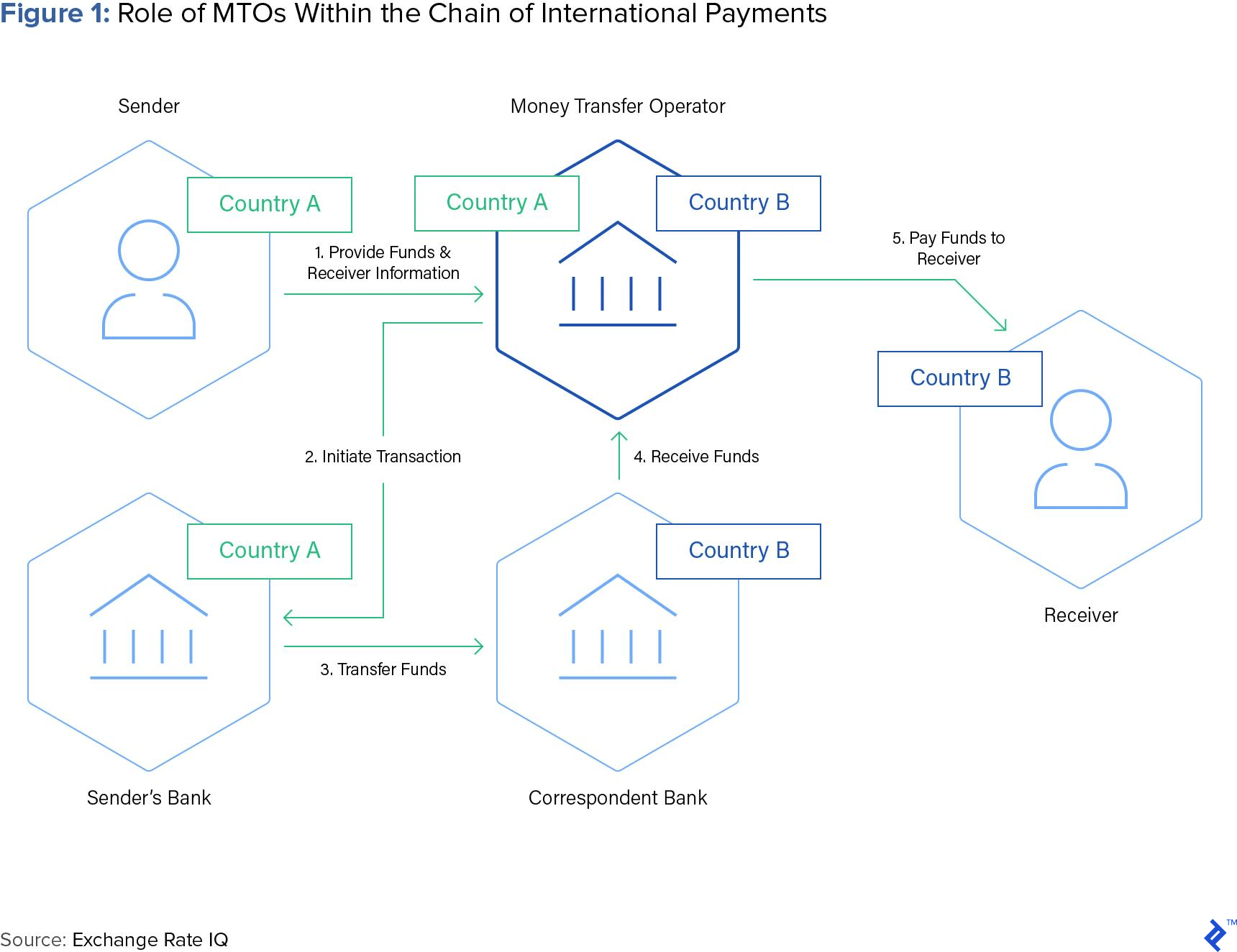

Money transfer operators (MTOs) are facilitators of international payment transactions. The IMF provides a clear definition of what these entities are:

Money transfer operators are financial companies (but usually not banks) engaged in cross border transfer of funds using either their internal system or access to another cross-border banking network.

The complexities of different currencies and banking systems means that sending money from one country to another is completely different from a domestic transfer. A visualization of the role an MTO plays in international transfer is shown below:

In this article, the key challenges of the MTO sector will be outlined, and three significant industry players will have their strategies analyzed to provide a clearer understanding of how the sector is evolving and what potential there is for investors to realize returns from the industry.

Remittances: Fees Are Falling and MTOs Dominate

International money transfer is commonly referred to as “remittances,” and this sector is often called the remittance market. The World Bank defines these transactions as:

Personal remittances is the sum of personal transfers and compensation of employees …Personal transfers include all current transfers in cash or in kind between resident and nonresident individuals, independent of the source of income of the sender

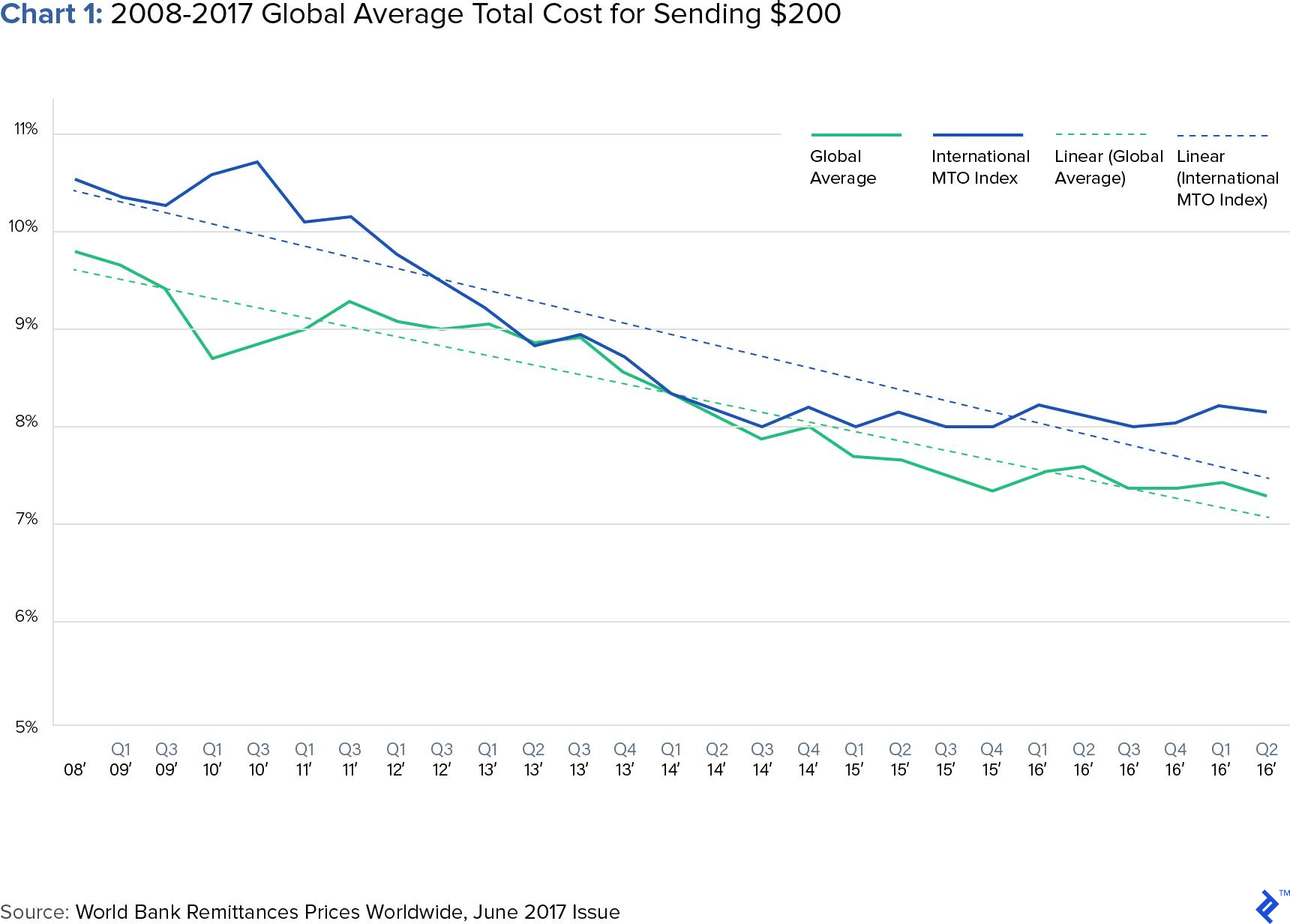

According to the World Bank, total remittances sent in 2016 were above the $530 billion mark and have grown at a CAGR of 10.4% since 2000, representing a significant global services market. The average cost for senders of remittances in Q3 2017 was 7.21% (of the total principal sent), which follows a trend of declining costs, as can be seen in Chart 1 below:

Costs have been falling as a result of healthier competition in the remittance industry and due to pressure from the G20 and the UN, who are targeting an average cost to consumer of 5% respectively. These bodies pay particular attention and effort to the remittance services market due to its popularity with low-wage workers and the role remittances play in economic development in emerging markets. Banks are facing the highest pressure from this drive to reduce fees, as they are the most expensive remittance providers, with an average cost (World Bank Q3 2017) of 11.0%, compared to MTOs at 6.1%.

Looking at the corridors of remittance, Charts 2 and 3 below show the most popular routes for money to flow. The underlying pattern shows that money is generally sent from economically developed countries to developing ones, corroborated by the fact that the USA and India send and receive, respectively, the most money. Incidentally, China ranks high for both sending and receiving money, with both directional volumes growing fast relative to peers. All countries in these rankings are showing strong growth, which indicates that the $530 billion sized remittance market has not yet plateaued into a mature phase:

In terms of who is handling the remittances, MTOs dominate the market. Western Union has more than double the market share of its nearest competitor, UAE Exchange. Despite payments and remittances receiving attention from new fintech startups, within the top five providers by volume there is only one recent newcomer, Transferwise. Chart 4 below shows the competitive landscape of the market.

The Pressure to Lower Fees Is Affecting MTOs

The heavy pressure exerted by international organizations (G20, UN, etc.) on remittance companies to lower the costs of remittances for users is placing its main players under increased scrutiny toward their prices. Considering that banks charge the highest prices, one would expect them to be feeling the most pressure from this movement, but banks are diversified organizations with many other sources of revenue. International payments is not a core service for a bank, compared to an MTO, which is their entire raison d’être. Revenue for international money transfer companies is divided into two parts: a transaction fee and the foreign exchange (“FX”) spread charged to the consumer. Western Union, for example, had a split of 70% and 27% between fee and FX revenue respectively in its 2016 results.

New players entering the remittance market are increasing the levels of competition, using fees as a tangible differentiator to position against incumbents. Building their business models on pure digital platforms also provides them with lower fixed costs and their modern, cleaner technological operational platforms offer consumers quicker turnaround times. As the industry moves towards one with the characteristics of a commodity market, players are having to find new ways to differentiate themselves from the competition. This can be through services like prepaid debit cards or payroll services for business, all of which offers the consumer more choice and utility. A comparison of what the major players offer is shown below:

To better analyze how the changes in the market have affected the fortunes of its players, let’s now look at the strategy and results of three major MTOs: Western Union, Transferwise, and Xoom. The former is the main incumbent of the market, while the latter two have emerged since the turn of the century and have each made their own distinct mark on the industry. The examples of both Transferwise and Xoom can show that there are positive opportunities for investors within this sector.

Western Union: Facing Downward Pressure on Fees

Western Union is the largest MTO by dollar volume traded and, subsequently, it is a prime target for disruption by newcomers. Its hold over the market comes from an established and large network of brick and mortar affiliate branches, which bring physical convenience and brand awareness alongside a steady introduction of value-added services that have attracted corporate customers. One such example of these is Edge, a marketplace platform for customers to discover new clients and transact.

However, as can be seen in Chart 5 below, its revenue growth has stagnated and its composition blend has been changing. In the face of higher fee competition, its relative share of revenue coming from fees has been decreasing, dropping to 70% in 2016 from 72% in 2014. Conversely, FX revenues have increased during the same time to 27% from 25%:

Western Union has tried to compensate for its stagnating revenue growth by diversifying its streams. There has been a focus on increasing FX revenue, which in absolute terms, has not increased faster than the decline in fee charges. To me though, this comes across as a misguided and short-termist approach, as it’s merely moving the cost a customer pays from one hand to another. Techcrunch noted this approach:

Essentially, it tells you what the exchange rate it cooked up is, but not what the real one is. Western Union pockets the difference

FX rates change every split-second, so it can appear more opaque from a customer’s perspective in comparison to flat linear transfer fees. However in the long term, charging a customer more on FX will be to its detriment, as newer companies are following a strategy of being up front and transparent with these cost items. More effective market research about the changing competitive environment of international payments would have highlighted earlier to Western Union the shift towards FX rate transparency.

Despite these issues, Western Union is still the largest MTO by transfer volume, with $80 billion exchanged in 2016. Due to the infrastructure that it has created and accessibility provided by its branch network, it’s safe to say that its position is not under threat in the short-to-mid term. A cause for concern, though, is the effect a continual stagnation of revenue growth will have on the remittance business’ ability to service its vast network and retain relevance. As with many famous instances of disruption, Western Union is paralyzed by newcomers offering a simpler service delivery format, which restricts its ability to respond due to its complex physical logistics (it has 500,000 agents) and threat of cannibalization of existing business lines.

Transferwise: Competing on Price, but Scaling Toward Greater Things

As the largest Fintech “newcomer” in the MTO space, Transferwise is well positioned to become a major force in the industry.

Transferwise is a privately-owned, venture capital-backed company formed in Estonia in 2011. September 2017 news about an impending funding round shed light on its recent performance, where it is targeted to make revenue of $100 million in 2017 and holds a 10% share of the UK money transfer market. With $117 million of capital already raised, its valuation is predicted to reach $1.6 billion at its next fundraising round and the business is now breaking even. It seems that Transferwise has hit an inflection point and investors have continually backed it:

What is surprising about the success of Transferwise is that it appears to be making magic happen on razor-thin margins. The business famously does not earn any FX spread on its transactions and only charges clients a fee, which is at competitive prices versus its peers. It claims to use a peer-to-peer model of matching customers’ transactions off against each other, which negates its needs to transfer currencies manually (and expensively) via transactions with third parties in the interbank market.

The effectiveness of this peer-to-peer system as a method to reduce costs is debatable, since it depends on an equal volume of money being transferred at the same time, in both directions, to make it work. Referring back to Charts 1 and 2, you can see that, with exception of China, money flows between countries in lopsided patterns. Considering that Transferwise is passing on midmarket rates to all consumers regardless of whether peer-to-peer matching is possible, it would be feasible to suggest that it is losing money on FX, considering its own operational costs and whether it itself actually has the luxury to transact at midmarket rates.

So without any FX revenue, Transferwise focuses solely on fees for transfers, which at 0.5% for EUR to USD, are very attractive to consumers. Transferwise is offering this in a viable way by building out its business in a purely electronic, virtual manner. It has no branch infrastructure and only offers electronic transfer options, so customers cannot pick up cash in agent bureaus. If the business is now breaking even, this suggests that it has built up an efficient technological operation for dealing with money transfer processes, such as onboarding, KYC checks, and balance reconciliations.

Where Will It Go Next?

A hint at future revenue expansion was seen in 2017 when Transferwise launched the Borderless Account. This service offers customers virtual bank accounts, allowing them to be paid directly by third parties and then make distributions to physical accounts via traditional transfer. A natural progression of this strategy would be offering physical cards or NFC pay services, which would move the business toward capturing day-to-day consumer transactions alongside one-off international ones.

If Transferwise does move toward acquiring a banking license, it would gain more flexibility to offer different services (such as lending), but its costs could rise substantially due to increased regulatory and compliance requirements. The advantages of this for the business could be profound, though, as maintaining passive customer balances will provide working capital support to offset the large swings that come with the territory of international money transfer services.

Transferwise has built a niche for itself by capitalizing on the intergovernmental organization’s goals of reducing money transfer costs. It has branded itself well by passing on attractive FX costs to consumers and then charging low and transparent fees. Its guerilla marketing stunts have attracted notoriety for attacking the high costs that other providers charge:

Its growth has allowed it to build a platform of customers that have validated the service and allowed it to iterate an efficient technological proposition. With the business now working at scale, it can use its customer base to build further revenue opportunities via flexible API interfaces and ambitious plans for transactional banking.

Xoom: The Blueprint for Exit Strategies

After IPOing in 2013, Xoom was acquired by PayPal for $890 million in 2015; following in the footsteps of its famous acquirer, it provides an example of a successful exit for investors in a remittance company.

The service offered by Xoom is only available for consumers sending from the USA, but as demonstrated in Chart 2, this is the largest country market for sending money. This is a very narrow offering compared to the other two companies analyzed above; however, as Xoom is now a part of PayPal, a giant of the payments industry, both businesses can now upsell their customers complimentary services. PayPal has always been a pure electronic play for both consumers and businesses, but within the realm of payments, credit facilities, and invoicing.

The focused nature of Xoom contributed to its successful exit. It did not try to be everything to everyone, but instead served its segment well. This provides a lesson to investors who may get swept away by a company’s ambitious plans to take over all elements of money transfer but who then become overwhelmed by the operational effort required to succeed. Xoom was an attractive company to PayPal because of the strength of its affiliate network around the world, which facilitated payouts in cash, mobile topup, and bank transfer.

As noted by Forbes, Xoom allowed PayPal to “strengthen its international business,” especially in emerging markets. Former Xoom CEO John Kunze noted that the synergies from this were mutually beneficial:

Becoming part of PayPal… will help accelerate our time-to-market in unserved geographies

Before the acquisition, Xoom was placing pressure on Western Union through combining online send with offline receive. Customers would send money electronically via its website/app, but recipients could choose electronic or physical collection options at their end. The value of the business to PayPal therefore was to harness the offline elements while combining its own online ecosystem with Xoom to create an integrated service for both sets of customers.

MTOs Are on a Race to the Bottom: Differentiation and Capturing More Customer Touch Points Is Key

In the scenarios described above, MTOs need strategies to cope with lower fees and increased competition from technology, which is enabling upstarts to ramp up new operations quickly. All three examples show characteristics of how players can look to compete within a market that is becoming a commodity. The directives from the G20 and UN to reduce prices is stimulating a price war and offering an easy point of differentiation for newcomers to attract new customers. With the race to the bottom on prices becoming apparent, incumbents must find efficiency improvements and offer different value added services to stand out from the crowd.

Value added services is the en-vogue trend to offer now, which should give the established players an advantage due to their high traffic and decades of customer data. The question is whether they have the means to analyze this data in a commercially useful manner and whether their legacy systems allow for it without a significant investment in data mining tools.

There are many routes to take to find future growth; for example, Western Union is chasing businesses with its enhanced options for hedging and marketplace to connect buyers and suppliers, while Transferwise is targeting the consumer and moving down the road of becoming a bank. Both options provide the potential to encourage customers to make more transactions, which is how MTOs make money. It also makes the customer sticky, as the switching costs become more painful for them to move to a competitor.

Conclusion: There Are Three Sources of Value in an MTO Business

As highlighted in a previous Toptal article, payments businesses do not actually transfer money; they use other service providers’ infrastructure. In the case of MTOs, they have grown in prominence due to an increasingly internationally mobile population and their own dogged determination to do the ugly job of sending money, packaged up into a more compelling service than bank offerings.

The examples in this article suggest that there are three sources of value (beyond obviously P&L) in an MTO, which will determine the success and investment potential of the business:

-

Brand Strength: Winning customer trust and engagement.

-

Options for sending and receiving money: The array of countries and transfer options provided to customers is an advantage gained from having a deep bench of agents and correspondent banks.

-

Quality of technology: In a low-margin business, powerful technology is required for reconciling transfers, managing working capital risk, and observing customer trends

The valuation potential of remittance companies depends on how many of these advantages they hold. For example, Xoom was an attractive business for PayPal due to the strength of #2, while it’s likely that Transferwise will continue to rise in value, due to its strength across all of the points.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

How does a remittance work?

Remittances are personal money transfers sent from workers in one country back to their country of origin. Due to different currencies and monetary systems, a remittance is processed by Money Transfer Operators (MTOs), who convert and transfer the money.

What is a remittance transfer provider?

Remittance transfer providers are traditionally called Money Transfer Operators (MTOs). They are non-bank entities that use networks of agents and banks to process payments and transfers across borders.

What is inward and outward remittances?

Inbound remittances are transfers received by the end user; they class as capital inflows into a country. Outbound remittances are the opposite, capital outflows from the money’s country of origin

How long does it take for international payments?

International payments can take between one and seven days to fully clear. The range is due to system complexity; some are relatively fast while others have regulatory processes that delay completion. Some MTOs speed up the process by using their own working capital to complete transactions earlier.

What is meant by cash remittance?

Cash remittances are transfers made in paper cash and received in paper cash at the recipient end. The MTO making the transfer will still need to complete the process electronically, so the process requires more complex financial management and compliance to check against money laundering.

Mauro F. Romaldini, ACMA CGMA

London, United Kingdom

Member since March 20, 2017

About the author

Mauro has led origination efforts for over $150m of private placement bond deals and built up finance teams for a range of startups.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT