M&A Negotiation Tactics and Strategies: Tips From a Pro

Mergers and acquisitions are headline-grabbing events that are often the pinnacle of a CEO’s career. But they also often fail to generate value, as numerous studies over the years have shown.

With over 15 years of experience doing M&A deals, Toptal Finance Expert Javier Enrile shows that the main reason for disappointing results is simple: Most people think M&A is merely an exercise of agreeing on a price for the deal. What they fail to understand is that there is a science to doing M&A that often makes the difference between a deal being successful or not.

In this article, Enrile runs through three key tactics for ensuring your company can get the most value out of an M&A transaction.

Mergers and acquisitions are headline-grabbing events that are often the pinnacle of a CEO’s career. But they also often fail to generate value, as numerous studies over the years have shown.

With over 15 years of experience doing M&A deals, Toptal Finance Expert Javier Enrile shows that the main reason for disappointing results is simple: Most people think M&A is merely an exercise of agreeing on a price for the deal. What they fail to understand is that there is a science to doing M&A that often makes the difference between a deal being successful or not.

In this article, Enrile runs through three key tactics for ensuring your company can get the most value out of an M&A transaction.

Javier Enrile

Javier has 16 years of experience in mid-market M&A and VC, with 35 completed transactions and hundreds of others evaluated and negotiated.

Expertise

Executive Summary

M&A deals are hard to get right.

- If not done correctly, M&A deals often don't work out. A recent study by S&P Global Market Intelligence found that the share prices of companies that had made an acquisition tended to underperform the broader index.

- In fact, many times M&A deals actually destroy value, as a study by consulting firm LEK showed.

- However, if done properly and with careful preparation, M&A can be a game-changing and transformative events in the life of any company. An example of this is Disney. Over the last decades, Disney has consistently extracted significant value from its numerous acquisitions and grew shareholder value in line with Google and other tech companies.

Legal documentation helps manage risk.

- The M&A negotiation process is often misperceived as simply a process of striking an agreement on the purchase price, forgetting the just-as-important risk allocation exercise which occurs in the negotiation of definitive contracts.

- The legal framework creates the structural edifice of the negotiation process and serves four main purposes: (1) memorialize in detailed legal language the business understanding between the parties, (2) allocate risks, (3) gather more information, and (4) set out the consequences to each party when things go wrong.

- The legal framework can be divided into two main phases: the first phase encompasses the Letter of Intent (LOI) (also called a Term Sheet or Memorandum of Understanding) and the second phase includes the definitive contracts and the due diligence process which aim to transform data into intelligence to guide the negotiation process.

Negotiating strategies can make a huge difference.

- I often hear authoritative acronyms like BATNA or ZOPA as tools to navigate the negotiation process. These are concepts based on the premise that human beings are rational actors which is, however, not the reality. My strong belief is that what drives our decisions and behavior is an invisible basic impulse, shaped by our deeply entrenched habits, fears, needs, perceptions, and desires.

- Negotiation theory has evolved considerably since its beginnings in 1979 with the formation of the Harvard Negotiation Project which assumed people were "rational beings".

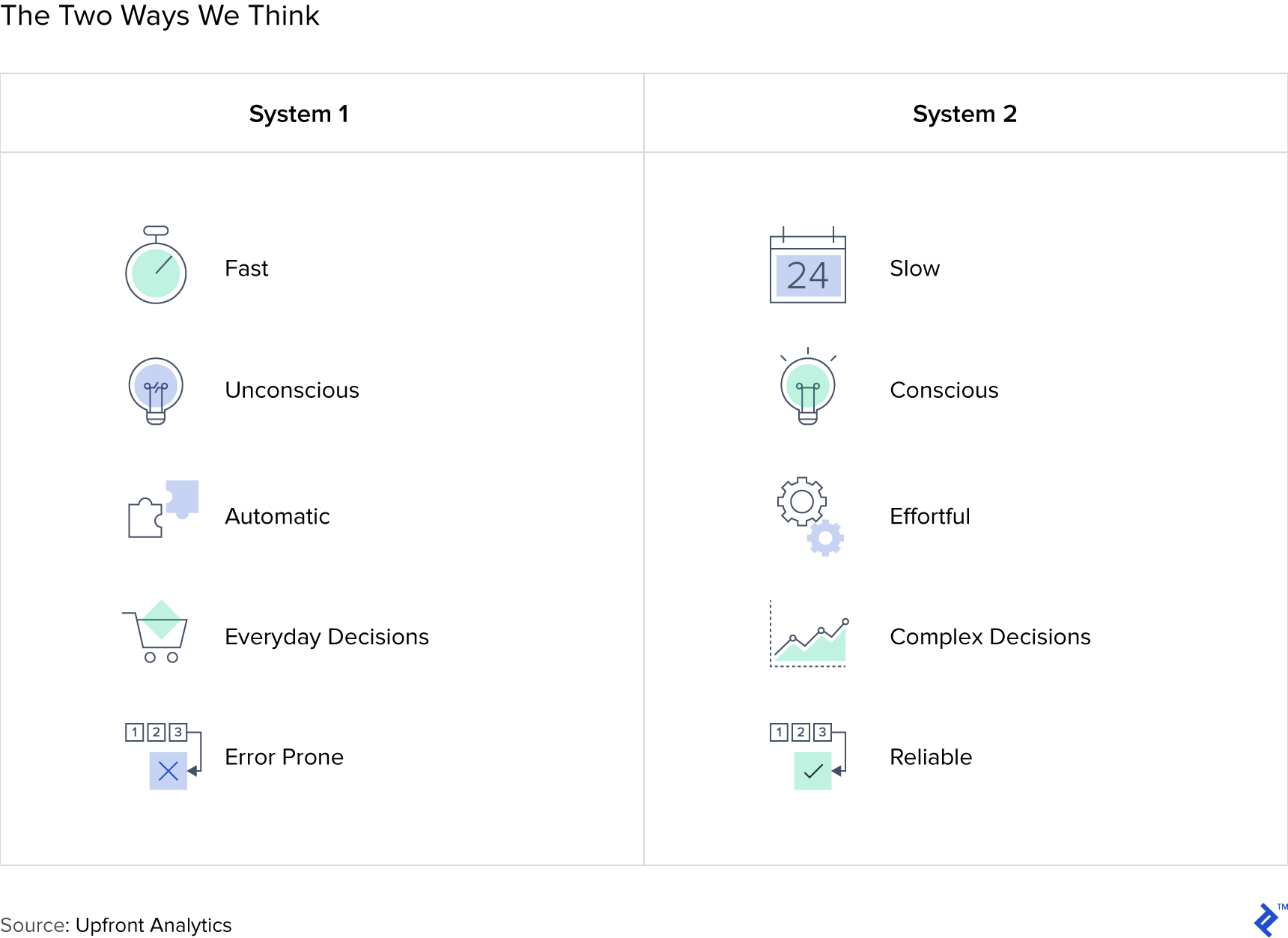

- Based on my 15 years as an M&A practitioner, I am a firm subscriber to a newer school of thought coming out of the University of Chicago and which was immortalized in the 2011 bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow which declares that humans have two systems of thought: System 1 which is our basic impulse - instinctive, emotional, irrational, and System 2 which is deliberate and logical. System 1 guides and steers System 2.

Preparation and planning are not chores, they're fundamental.

- A consistent, disciplined investment process is a driver of good outcomes and an enabler of good judgment in decision-making. In particular, it helps avoid deal frenzy and ensures consistent analytical rigor.

- When it comes to preparation, the main ways to be ready for the twists and turns of a highly intense negotiation process are to (a) gather information on the counterpart and, (b) have sound valuation analysis in place.

- The negotiation process is lengthy and requires a vast amount of information exchange. Having a process to exchange information and facilitate decision-making is vital.

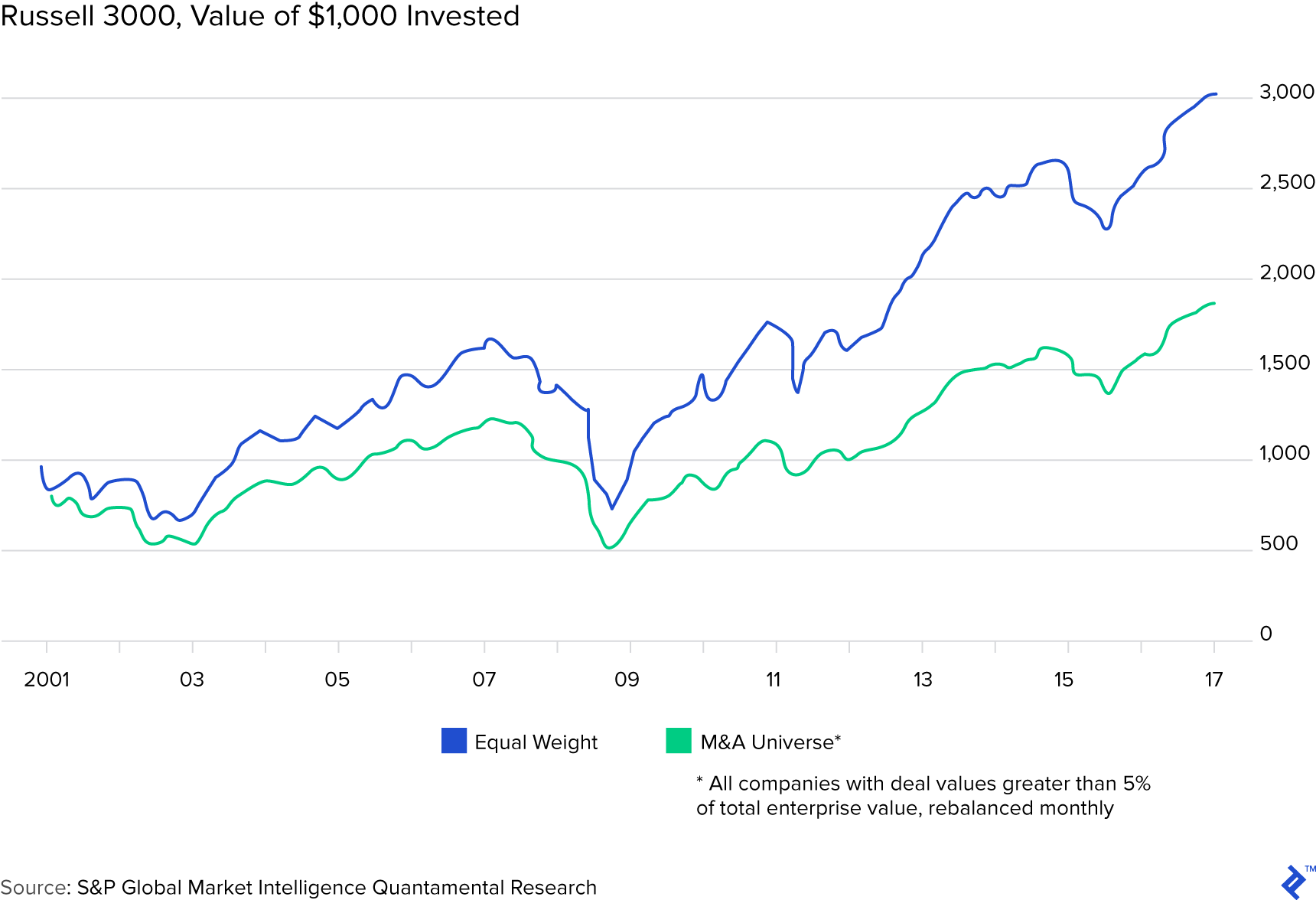

In the professional life of a CEO, a merger or acquisition can be one of the most exciting events that take place, if not the pinnacle of one’s career. M&A deals are headline-grabbing events that can propel companies to levels that organic growth alone would otherwise never have been able to reach. But as many studies show, M&A deals often don’t pan out quite the way they were planned. A recent study by S&P Global Market Intelligence, for instance, showed that share prices of firms in the Russell 3000 index that had acquired a company between January 2001 and August 2017 tended to underperform the broader index. As for the reasons for this disappointing performance, the same study found that relative to the peer group, acquiring company net profit margins tended to fall, as did the returns on capital and on equity. Earnings per share also grew less quickly, and debt and interest expense figures tended to increase.

Over my two decades as an M&A practitioner in private equity, venture capital, and corporate roles, I’ve worked on enough deals to know why the above happens, and it usually comes down to a simple fact. Most companies approach M&A deals incorrectly, thinking that it is merely an exercise of agreeing on a price between both parties. What they fail to understand is that there is a science to doing M&A deals that often makes the difference between a deal being successful and not.

The purpose of this post is to highlight three important ways in which companies can better prepare and execute M&A transactions to maximize their chances of success.

The Fineprint Matters: Using Legal Documentation to Effectively Manage Risk in the Negotiation Process

In 20 years of working on M&A deals, I’ve heard the following sentence from both buyers and sellers far too many times: “Javier, thank you for getting the purchase price agreed and term sheet done, let’s send it to the lawyers to put it in writing and call it a day.” Or even more worrisome, “These contracts are a maze of mumbo-jumbo which I don’t care about, the relationship is what matters”. The M&A negotiation process is often misperceived as simply a process of striking an agreement on the purchase price, forgetting the just-as-important risk allocation exercise which occurs in the negotiation of definitive contracts. Some market participants have not gone through a bad experience (e.g. when the target firm is not what it was supposed to be), in an M&A transaction and therefore lack the tacit knowledge of the importance of having well-negotiated definitive contracts. This is often the difference between losing all the capital at risk or recovering 80% or 90% of it.

The legal framework creates the structural edifice of the negotiation process and serves four main purposes: (1) memorialize in detailed legal language the business understanding between the parties, (2) allocate risks, (3) gather more information, and (4) set out the consequences to each party when things go wrong.

The legal framework can be divided into two main phases: the first phase encompasses the Letter of Intent (LOI) (also called a Term Sheet or Memorandum of Understanding) and the second phase includes the definitive contracts and the due diligence process which aims to transform data into intelligence to guide the negotiation process.

Before arriving at the Letter of Intent, the two sides have little to show but a degree of conviction that the potential transaction meets their respective strategic objectives and some sense of the level of chemistry between the management teams. The purpose of the LOI is to set the key terms of the deal: the price, form of payment, and structure. It also serves as a means to confirm the understanding, express commitment to the transaction, and set the ground rules for future negotiations. While in some cases practitioners opt to skip this phase and move directly into phase II on the grounds that it saves time and cost, I always recommend to take the time and effort to draft and negotiate an LOI to ensure that there is agreement on the main terms before diving into the lengthy and costly process of performing due diligence and negotiating definitive contracts.

How the LOI is negotiated has significant consequences for buyers and sellers. In particular, sellers risk leaving substantial economic value on the table and compromising on strategic deal terms whereas buyers can lock themselves into positions that need to be reversed in phase II and expose themselves to legal risks that may prevent them from walking away from the deal. Therefore, parties should seek expert advice on the negotiation and drafting of LOIs.

A typical LOI for a middle market firm will look similar to this:

Sample Term Sheet

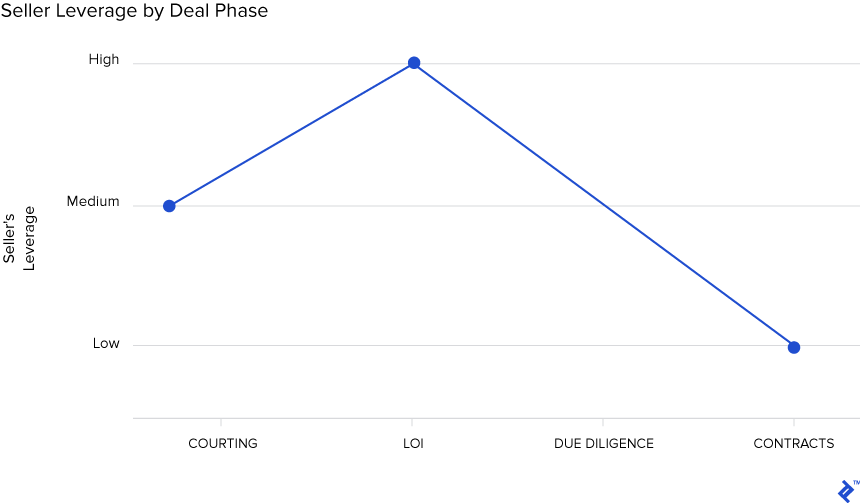

The use of negotiating leverage at different phases of the deal to increase negotiating strength is a perfect example of how having expert advice ensures effective negotiations. A key point on negotiating an LOI is to understand how negotiating leverage shifts as the deal cycle moves along. The seller achieves the maximum leverage right when the LOI is being negotiated as they can exploit the competitive tension created by having many buyers interested. From that point on in the deal cycle, the seller’s leverage declines while the buyer’s leverage increases. After the LOI has been signed, typically the seller will be in exclusive negotiations with one buyer (or at most, two) which decreases the competitive tension mentioned above. In addition, with the passage of time, one or more of these circumstances could arise: (1) the content and terms of the LOI could be leaked, potentially causing several complications (e.g., employees could get nervous and start seeking other jobs or customers may become concerned about whether the new owner will increase prices or fail to provide the same level of service which may lead them to look for another provider), (2) a seller can also get emotionally attached to the idea of the sale and begin thinking about ways of spending or investing the proceeds, or, if they are owner-executives, moving on to other activities (including retirement). All of these circumstances reduce the seller’s leverage as it makes it harder for a seller to resist demands from the buyer after the LOI is signed. The phrase “becoming wedded to the deal” is an apt one.

Practitioners have unique insight on how the leverage shifts on each step of the negotiation process and use this insight to obtain the best possible outcome. For example, buyers should attempt to keep the LOI short and more general, deferring negotiating key issues in the definitive contracts phase where their leverage level has increased. Conversely, sellers should attempt to have the LOI as detailed and comprehensive as possible so that it takes advantage of its optimal bargaining positions. Below we show how the seller’s leverage shifts in each phase of the deal:

In contrast to the LOI, which is for the most part non-binding, definitive contracts are binding and set out all the details relevant to consummate the deal. The definitive contracts serve two vital purposes: (1) it helps to obtain additional information and allocates risk exposure, and (2) shapes the behavior of the parties during and after the transaction.

- Disclosure of information and allocation of risk: the representation (or “rep” is a statement of fact about the target firm; the warranty (or “warrants”) is a commitment that a fact is or will be true. These reps and warrants serve two key purposes: first, it provides additional information about the firm, recognizing that no amount of due diligence can reveal all information about a firm. The sellers are asked to make descriptive statements about their firm which the buyer can rely on for purposes of due diligence. Second, it shifts the risk of known or unknown circumstances which could reduce the value of the firm between the parties. For example, a typical representation is that the seller does not have any pending litigation. This shifts the risk of this negative event, i.e., pending litigation, to the sellers because if in fact after the transaction is consummated the buyer uncovers that there was pending litigation, the buyer has a legal basis to collect damages and recover part or all of the purchase price.

- Shaping behavior between signing and closing: covenants typically refer to the conduct of the firm and its management in the period of time between signing and closing which can take a number of months. This period is complex because on the one hand the buyer is legally obligated to close (unless the conditions to close are not met) but on the other hand, the buyer doesn’t own the firm yet. As a result, the buyer and sellers agree on a set of covenants that legislates the operations of the firm during this period.

Below is an example of the wording for two of the most typical warranties related to litigation and financial statements, and also a set of typical covenants:

Sample Warranties and Covenants

Negotiation Theory and Tactics

One of the most underappreciated aspects of M&A negotiation relates to the tactics and strategy that stakeholders use. I often hear authoritative acronyms like BATNA or ZOPA as tools to navigate the negotiation process. These are concepts based on the premise that human beings are rational actors which is however not the reality. An example that comes to mind was during the early phase of an LOI negotiation. I had emailed a detailed opening purchase price bid which by all measures was at least a market offer. Wanting to show my commitment I proposed a meeting in person to get the seller’s response and counter. The setting was a stuffy, big conference room at a long table with the entire management team from both sides. After a brief round of introductions, the sellers CEO, having stared at me in silence for thirty seconds, said: “Javier the offer is cheap, and you are cheap.””

This example, although a bit extreme, illustrates my strong belief that what drives our decisions and behavior is an invisible basic impulse, shaped by our deeply entrenched habits, fears, needs, perceptions, and desires. In the example above, the seller’s CEO had a basic impulse to crush whoever was against him based on the perception that that was the way to handle the opposition, even if it means to lose a perfectly attractive offer.

Negotiation theory has evolved over the years, the first school of thought has its beginning in 1979 with the formation of the Harvard Negotiation Project. Two years later, Roger Fisher and William Ury – co-founders of the project – came out with the book Getting to Yes, which became the bible for negotiation practice. In their work, the core assumption was that the emotional brain (or the basic impulse as I like to define it) could be overcome through a more rational, joint problem-solving mindset. Their system was simple and easy to follow with four basis tenants: (1) separate the basic impulse of the person from the problem, (2) focus on the other side’s interest rather than their position, (3) work cooperatively to find win-win options, and (4) establish agreed standards to evaluate these possible solutions.

Practitioners needed to assume that we are “rational actors” so in the negotiation process one assumed that the other side was acting rationally and selfishly in trying to maximize his/her position, the goal was to figure out how to respond in various scenarios to maximize one’s own value.

A different school of thought emerged at the University of Chicago in and around the same time where economist Amos Tevesky and the psychologist Daniel Kahneman assumed humans are “irrational beasts” rather than rational actors. They concluded that a key characteristic of the human condition is that we all suffer from Cognitive Bias that is unconscious and irrational brain processes that distort the way we see the world. Kahneman illustrated all his research in the 2011 bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow where he declared that man has two systems of thought: System 1, our basic impulse which is instinctive, emotional, irrational, and System 2 which is deliberate and logical. He concluded that System 1 guides and steers System 2.

I am a firm subscriber to the second school of thought. I arrived at this conviction through two different paths: first during my 15 years of experience negotiating deals I have seen evidence over and over again that the basic impulse overrides rational behavior. Second, over the last 10 years, I have been investigating how my own mind works through contemplative practices which have reinforced my belief that basic impulses drive how reality is perceived which in turn shapes how decisions are made.

So, if one believes that your counterpart in a negotiation is an “irrational beast”, what in the world can you do? In this paragraph, I offer six practical tactics whose main objective is to neutralize negative basic impulses and leverage the positive ones in order to increase the probability that the counterpart accepts your asks. I describe each tactic and a real-life example to illustrate the use of it:

-

Observe and understand habitual tendencies: while behavior is difficult to predict, habits are very predictable as human beings are “habitual animals”. During the first days of the negotiation, observe the habitual tendencies of your counterpart so you can leverage this insight in your favor.

For example, in a recent transaction, I observed that the lead negotiator (the seller’s CEO, in this case) on the other side had the following habitual behavior: during group negotiations where lawyers and other members of his management team were present he took a very hard line and rarely compromised; however, in private one-on-one conversation with me, he was more open and willing to compromise. No doubt, this was an example of how the basic impulse, in this case, the need to preserve self-esteem (or “face”) in front of his own management team was driving this habit. Armed with this insight, I changed the process and conducted all the negotiations on a one-on-one basis which accelerated progress by neutralizing this particular basic impulse. -

Use the negotiation process itself as a systematic intelligence gathering exercise: observe how the counterparty reacts and counters to the initial terms and the subsequent changes as the process goes along. This is the best way to extract the insight of what really matters, i.e., his/her tradeoffs. The basic impulse getting in the way, in this case, is the fear of being taken advantage of if the counterparty “knows too much” which then limits the information shared between parties. This tactic recognizes the problem and finds an alternative technique to unearth what matters to the other side using the bargaining process itself.

For example, towards the end of the negotiation process in a deal, we uncovered, through due diligence, that a key revenue producer for the target firm and a key component of our forecast was at risk. Armed with this new information, we went back to the target to let them know that we were reducing the price. The target understood (see section below) but did not give us any indication on what element of the purchase price (in this case, the purchase price was highly structured) he had flexibility. As a result, we used this tactic and changed one element at the time until we got to the one the target had flexibility on. -

Carefully examine the form and channel used to present proposals and counters: the way the proposal is presented has an important effect on how it is perceived and as result on the outcome; therefore, careful planning and execution is needed.

Using the same example above, I carefully thought about the form and channel to use in order to deliver the news to the target firm that we were lowering the purchase price. First, rather than having a group setting, I asked the lead negotiator to meet in private in order to “maintain face”. In terms of the form, I opened the conversation by explaining in great detail what we have found and reminded him that this particular client was on his management forecast. Then, I posed the question to appeal to his sense of fairness, “John, this new information makes the cash flows associated with this client much more uncertain. Am I supposed to leave the price the same?” -

Never say “no” immediately, even if the ask is unreasonable, instead replace it with “let me see what I can do”: building a sense of trust and empathy is imperative in these long negotiation processes. The basic impulse at play, in this case, is the universally applicable premise that human beings want to feel heard and accepted. This tactic leaves an emotional imprint in your counterpart’s brain that you are committed to making things work and that you understand how it is to be in their shoes.

For example, in another deal, I was negotiating with a target firm with four different partners, who all had very different perspectives. As a result, their positions kept changing which meant having to negotiate the same terms multiple times. As the changes kept on coming I always listened and took away the ask to consider it. All four partners, after the deal was done, commented that while negotiations were tough they always felt heard and understood even if the final answer was no, which in turn increased their willingness to compromise. -

Conduct multi-issue bargaining: attempt to negotiate multiple issues simultaneously and as a package rather than performing a one-issue-at-a-time negotiation process. This reinforces the sense of fairness and equality as both the buyer and seller give in but also gain.

Effective Preparation and Management of the Negotiation Process

Finally, a third crucial way of maximizing the chances of success in an M&A deal has to do with two simple, but often forgotten points: preparation and management. A consistent, disciplined investment process is a driver of good outcomes and an enabler of good judgment in decision-making. In particular, it helps avoid deal frenzy and ensure consistent analytical rigor.

When it comes to preparation, the main ways to be ready for the twists and turns of a highly intense negotiation process are to (a) gather information on the counterpart and, (b) have sound valuation analysis in place. The following are five practical to do’s that should precede any negotiation process:

- Assess both parties’ strategies: develop a full understanding of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of both the seller and buyer

- Value the target: conduct extensive valuation analysis so that one has a high level of conviction of the value of the target firm and also what key factors affect value the most

- Determine the opening bid and walk-away price: refine the strategic and valuation analysis so that you have a high level of conviction on the opening bid price and the walk-away or reservation price. The walk-away price becomes an important discipline on one’s conduct of negotiations and should only be changed if there is new information that changes the fundamentals of the target firm. The walk-away price serves as a defense mechanism against physiological tactics, such as anchoring.

- Consider the level of interest of each party to consummate the deal: there are certain circumstances which elevate the level of interest to a point where it could be exploited. In the case of the seller, typical circumstances are situations of financial distress, the need to sell a stake from an existing shareholder, and the belief that the market conditions are ideal and temporary. For the buyer, a typical circumstance is pressure to consummate a deal to show the market that excess cash is being deployed. If these circumstances exist and are known, they should be factored into the opening purchase price. For example, a seller that is in financial distress should be willing to accept a lower price in exchange for having the certainty of execution.

- Know who you are negotiating against: understand the reputation and habitual patterns of the counterparty. For example, knowing that your counterparty has a behavior of constant bluffs, threats, and ultimatums prepares you to use different tactics.

The negotiation process is lengthy and requires a vast amount of information exchange. Having a process to exchange information and facilitate decision-making is vital. The following four tactics facilitate a well-run process:

-

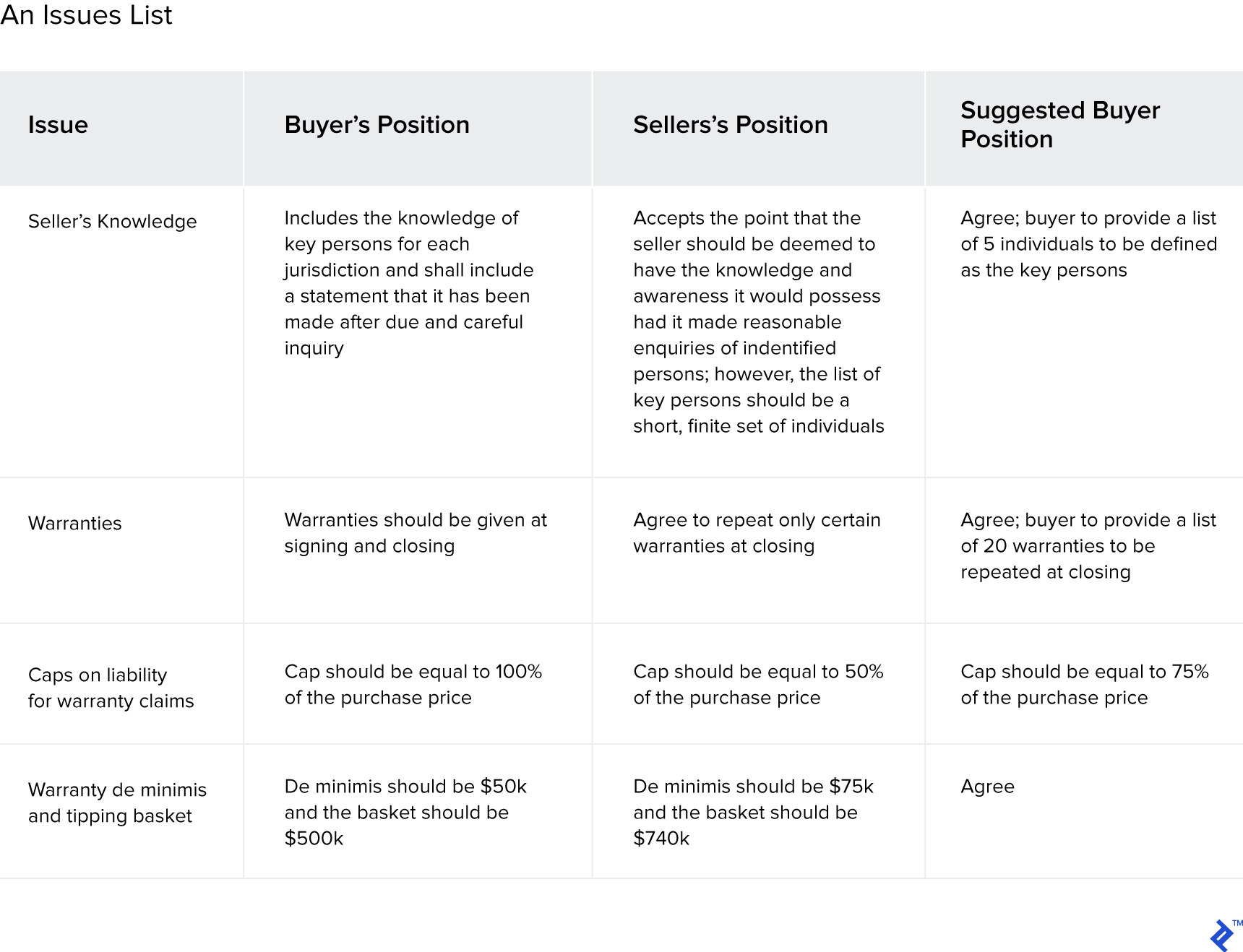

Develop an issues list to extract the most important issues arising from the definitive contracts. These lists should be used as the basis for the negotiation sessions to ensure the positions are clearly described and the agreements memorialized. The issues list is also used to record the history of a particular term so that one can see the full negotiation process for each term. This list should show the issue, the position of the seller, the position of the buyer and any notes. Below we show a sample of a part of an issues list:

- Ensure that the negotiation is a step by step process: having made a move, ensure that your counterpart reciprocates by either accepting or rejecting your proposal. This ensures that one party doesn’t negotiate against him/herself, which is a critical point. Additionally, reciprocity helps keep the other side at the bargaining table and the continued movement helps build a sense of momentum toward the goal, which helps the two parties find common ground.

- Manage time carefully: how time is managed could have positive and negative impacts. The passage of time, on the one hand, allows for parties to agree on a set of terms that are mutually beneficial, but on the other, it could give rise to fatigue and negative emotional situations. Deadlines are necessary to keep the process going but they could be interpreted as ultimatums. Therefore, the effective and careful management of time is a critical component of the process.

- Reflect due diligence findings into the contracts through the entire negotiation process: the intersection between due diligence and the negotiation process is an important one. Upon uncovering a new issue in due diligence, parties should expect to revisit terms already agreed.

Parting Thoughts: If Done Right, M&A Can Supercharge Your Company’s Performance

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned how a large majority of M&A deals don’t end up performing as planned. In fact, that’s probably an understatement. A study by consulting firm LEK of 2,500 deals found that more than 60% of these actually destroyed shareholder value.

But whilst the abundance of examples of failed M&A deals may turn you off pursuing such a path, I think that would be an incorrect conclusion to draw. In fact, there are similarly many examples of companies who, through M&A, have achieved tremendous success. One such company is Disney. In the last decades, Disney has closed numerous acquisitions (in fact, since 1993 it has made 12 acquisitions), the most high profile of which are: the acquisition of Pixar in 2006, the acquisition of Marvel in 2009, the acquisition of Lucas Films in 2012, and most recently may be about to buy 21st Century Fox.

Having done so many acquisitions, and having seen the probabilities of failure mentioned above, one would think that the chances of a failed Disney acquisition would be fairly high. Well, you’d be wrong. In almost all of Disney’s deals, the company has managed to extract significant value from the acquired companies, and in fact, six of its biggest eight acquisitions can be considered major successes. So much so that Disney’s market cap has tripled in a decade, a performance just shy of Google’s parent company, Alphabet.

Disney’s history of consistently successful acquisitions illustrates the point very clearly: M&A is not just an art, it is also a science. When mastered and performed correctly, it can unlock tremendous value for shareholders. By effectively managing your risk through the legal framework, by planning your negotiation tactics and strategy, and by preparing and managing the M&A process effectively, you can maximize your chances of success in an M&A event, and take your company to the next level.

Understanding the basics

What is strategic M&A?

Strategic M&A is when two companies merge because there is a strategic advantage for their companies to be united rather than remain separate. Often this can be for reasons of synergies and cost reduction, or a stronger competitive position.

Why do companies merge with or acquire other companies?

There are many reasons why companies merge or acquire other companies but some of the main ones include synergies (cost reductions), competitive strength, economies of scale, and pricing power.

What percentage of mergers and acquisitions fail?

Many mergers and acquisitions fail to generate significant value for investors, and in fact, a study by consulting firm LEK found that 60% of M&A deals actually destroy value.

What is an M&A specialist?

An M&A specialist is someone with intimate knowledge of the M&A process, including legal documentation, negotiation tactics and strategies, preparation and planning, and management of an effective process.