10 Kotlin Features to Boost Android Development

Kotlin is a new, expressive, general-purpose programming language powered by the same virtual machine technology that powers Java. Since Kotlin compiles to the JVM bytecode, it can be used side by side with Java, and it does not come with a performance overhead.

In this article, Toptal Freelance Software Engineer Ivan Kušt gives us a walkthrough of 10 major features of Kotlin that help avoid boilerplate code and, more importantly, save time.

Kotlin is a new, expressive, general-purpose programming language powered by the same virtual machine technology that powers Java. Since Kotlin compiles to the JVM bytecode, it can be used side by side with Java, and it does not come with a performance overhead.

In this article, Toptal Freelance Software Engineer Ivan Kušt gives us a walkthrough of 10 major features of Kotlin that help avoid boilerplate code and, more importantly, save time.

Introduction

A while ago, Tomasz introduced Kotlin development on Android. To remind you: Kotlin is a new programming language developed by Jetbrains, the company behind one of the most popular Java IDEs, IntelliJ IDEA. Like Java, Kotlin is a general-purpose language. Since it complies to the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) bytecode, it can be used side-by-side with Java, and it doesn’t come with a performance overhead.

In this article, I will cover the top 10 useful features to boost your Android development.

Note: at the time of writing this article, actual versions were Android Studio 2.1.1. and Kotlin 1.0.2.

Kotlin Setup

Since Kotlin is developed by JetBrains, it is well-supported in both Android Studio and IntelliJ.

The first step is to install Kotlin plugin. After successfully doing so, new actions will be available for converting your Java to Kotlin. Two new options are:

- Create a new Android project and setup Kotlin in the project.

- Add Kotlin support to an existing Android project.

To learn how to create a new Android project, check the official step by step guide. To add Kotlin support to a newly created or an existing project, open the find action dialog using Command + Shift + A on Mac or Ctrl + Shift + A on Windows/Linux, and invoke the Configure Kotlin in Project action.

To create a new Kotlin class, select:

-

File>New>Kotlin file/class, or -

File>New>Kotlin activity

Alternatively, you can create a Java class and convert it to Kotlin using the action mentioned above. Remember, you can use it to convert any class, interface, enum or annotation, and this can be used to compare Java easily to Kotlin code.

Another useful element that saves a lot of typing are Kotlin extensions. To use them you have to apply another plugin in your module build.gradle file:

apply plugin: 'kotlin-android-extensions'

Caveat: if you are using the Kotlin plugin action to set up your project, it will put the following code in your top level build.gradle file:

buildscript {

ext.kotlin_version = '1.0.2'

repositories {

jcenter()

}

dependencies {

classpath "org.jetbrains.kotlin:kotlin-gradle-plugin:$kotlin_version"

// NOTE: Do not place your application dependencies here; they belong

// in the individual module build.gradle files

}

}

This will cause the extension not to work. To fix that, simply copy that code to each of the project modules in which you wish to use Kotlin.

If you setup everything correctly, you should be able to run and test your application the same way you would in a standard Android project, but now using Kotlin.

Saving Time with Kotlin

So, let’s start with describing some key aspects of Kotlin language and by providing tips on how you can save time by using it instead of Java.

Feature #1: Static Layout Import

One of the most common boilerplate codes in Android is using the findViewById() function to obtain references to your views in Activities or Fragments.

There are solutions, such as the Butterknife library, that save some typing, but Kotlin takes this another step by allowing you to import all references to views from the layout with one import.

For example, consider the following activity XML layout:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<RelativeLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

tools:context="co.ikust.kotlintest.MainActivity">

<TextView

android:id="@+id/helloWorldTextView"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"/>

</RelativeLayout>

And the accompanying activity code:

package co.ikust.kotlintest

import android.support.v7.app.AppCompatActivity

import android.os.Bundle

import kotlinx.android.synthetic.main.activity_main.*

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main)

helloWorldTextView.text = "Hello World!"

}

}

To get the references for all the views in the layout with a defined ID, use the Android Kotlin extension Anko. Remember to type in this import statement:

import kotlinx.android.synthetic.main.activity_main.*

Note you don’t need to write semicolons at the end of the lines in Kotlin because they are optional.

The TextView from layout is imported as a TextView instance with the name equal to the ID of the view. Don’t be confused by the syntax, which is used to set the label:

helloWorldTextView.text = "Hello World!"

We will cover that shortly.

Caveats:

- Make sure you import the correct layout, otherwise imported View references will have a

nullvalue. - When using fragments, make sure imported View references are used after the

onCreateView()function call. Import the layout inonCreateView()function and use the View references to setup the UI inonViewCreated(). The references won’t be assigned before theonCreateView()method has finished.

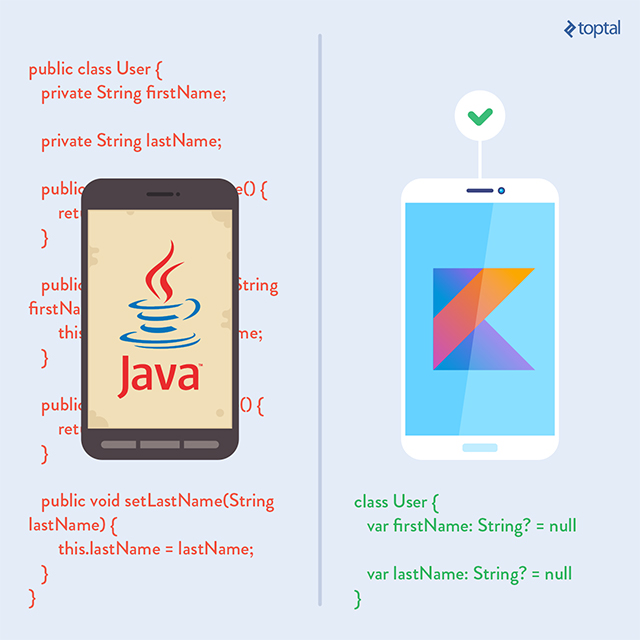

Feature #2: Writing POJO Classes with Kotlin

Something that will save the most time with Kotlin is writing the POJO (Plain Old Java Object) classes used to hold data. For example, in the request and response body of a RESTful API. In applications that rely on RESTful API, there will be many classes like that.

In Kotlin, much is done for you, and the syntax is concise. For example, consider the following class in Java:

public class User {

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

public String getFirstName() {

return firstName;

}

public void setFirstName(String firstName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public String getLastName() {

return lastName;

}

public void setLastName(String lastName) {

this.lastName = lastName;

}

}

When working with Kotlin, you don’t have to write public keyword again. By default, everything is of public scope. For example, if you want to declare a class, you simply write:

class MyClass {

}

The equivalent of the Java code above in Kotlin:

class User {

var firstName: String? = null

var lastName: String? = null

}

Well, that saves a lot of typing, doesn’t it? Let’s walk through the Kotlin code.

When defining variables in Kotlin, there are two options:

- Mutable variables, defined by

varkeyword. - Immutable variables, defined by

valkeyword.

The next thing to note is the syntax differs a bit from Java; first, you declare the variable name and then follow with type. Also, by default, properties are non-null types, meaning that they can’t accept null value. To define a variable to accept a null value, a question mark must be added after the type. We will talk about this and null-safety in Kotlin later.

Another important thing to note is that Kotlin doesn’t have the ability to declare fields for the class; only properties can be defined. So, in this case, firstName and lastName are properties that have been assigned default getter/setter methods. As mentioned, in Kotlin, they are both public by default.

Custom accessors can be written, for example:

class User {

var firstName: String? = null

var lastName: String? = null

val fullName: String?

get() firstName + " " + lastName

}

From the outside, when it comes to syntax, properties behave like public fields in Java:

val userName = user.firstName

user.firstName = "John"

Note that the new property fullName is read only (defined by val keyword) and has a custom getter; it simply appends first and last name.

All properties in Kotlin must be assigned when declared or are in a constructor. There are some cases when that isn’t convenient; for example, for properties that will be initialized via dependency injection. In that case, a lateinit modifier can be used. Here is an example:

class MyClass {

lateinit var firstName : String;

fun inject() {

firstName = "John";

}

}

More details about properties can be found in the official documentation.

Feature #3: Class Inheritance and Constructors

Kotlin has a more concise syntax when it comes to constructors, as well.

Constructors

Kotlin classes have a primary constructor and one or more secondary constructors. An example of defining a primary constructor:

class User constructor(firstName: String, lastName: String) {

}

The primary constructor goes after the class name in the class definition. If the primary constructor doesn’t have any annotations or visibility modifiers, the constructor keyword can be omitted:

class Person(firstName: String) {

}

Note that a primary constructor cannot have any code; any initialization must be done in the init code block:

class Person(firstName: String) {

init {

//perform primary constructor initialization here

}

}

Furthermore, a primary constructor can be used to define and initialize properties:

class User(var firstName: String, var lastName: String) {

// ...

}

Just like regular ones, properties defined from a primary constructor can be immutable (val) or mutable (var).

Classes may have secondary constructors as well; the syntax for defining one is as follows:

class User(var firstName: String, var lastName) {

constructor(name: String, parent: Person) : this(name) {

parent.children.add(this)

}

}

Note that every secondary constructor must delegate to a primary constructor. This is similar to Java, which uses this keyword:

class User(val firstName: String, val lastName: String) {

constructor(firstName: String) : this(firstName, "") {

//...

}

}

When instantiating classes, note that Kotlin doesn’t have new keywords, as does Java. To instantiate the aforementioned User class, use:

val user = User("John", "Doe)

Introducing Inheritance

In Kotlin, all classes extend from Any, which is similar to Object in Java. By default, classes are closed, like final classes in Java. So, in order to extend a class, it has to be declared as open or abstract:

open class User(val firstName, val lastName)

class Administrator(val firstName, val lastName) : User(firstName, lastName)

Note that you have to delegate to the default constructor of the extended class, which is similar to calling super() method in the constructor of a new class in Java.

For more details about classes, check the official documentation.

Feature #4: Lambda Expressions

Lambda expressions, introduced with Java 8, are one its favorite features. However, things are not so bright on Android, as it still only supports Java 7, and looks like Java 8 won’t be supported anytime soon. So, workarounds, such as Retrolambda, bring lambda expressions to Android.

With Kotlin, no additional libraries or workarounds are required.

Functions in Kotlin

Let’s start by quickly going over the function syntax in Kotlin:

fun add(x: Int, y: Int) : Int {

return x + y

}

The return value of the function can be omitted, and in that case, the function will return Int. It’s worth repeating that everything in Kotlin is an object, extended from Any, and there are no primitive types.

An argument of the function can have a default value, for example:

fun add(x: Int, y: Int = 1) : Int {

return x + y;

}

In that case, the add() function can be invoked by passing only the x argument. The equivalent Java code would be:

int add(int x) {

Return add(x, 1);

}

int add(int x, int y) {

return x + y;

}

Another nice thing when calling a function is that named arguments can be used. For example:

add(y = 12, x = 5)

For more details about functions, check the official documentation.

Using Lambda Expressions in Kotlin

Lambda expressions in Kotlin can be viewed as anonymous functions in Java, but with a more concise syntax. As an example, let’s show how to implement click listener in Java and Kotlin.

In Java:

view.setOnClickListener(new OnClickListener() {

@Override

public void onClick(View v) {

Toast.makeText(v.getContext(), "Clicked on view", Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

};

In Kotlin:

view.setOnClickListener({ view -> toast("Click") })

Wow! Just one line of code! We can see that the lambda expression is surrounded by curly braces. Parameters are declared first, and the body goes after the -> sign. With click listener, type for the view parameter isn’t specified since it can be inferred. The body is simply a call to toast() function for showing toast, which Kotlin provides.

Also, if parameters aren’t used, we can leave them out:

view.setOnClickListener({ toast("Click") })

Kotlin has optimized Java libraries, and any function that receives an interface with one method for an argument can be called with a function argument (instead of Interface).

Furthermore, if the function is the last parameter, it can be moved out of the parentheses:

view.setOnClickListener() { toast("Click") }

Finally, if the function has only one parameter that is a function, parentheses can be left out:

view.setOnClickListener { toast("Click") }

For more information, check Kotlin for Android developers book by Antonio Leiva and the official documentation.

Extension Functions

Kotlin, similar to C#, provides the ability to extend existing classes with new functionality by using extension functions. For example, an extension method that would calculate the MD5 hash of a String:

fun String.md5(): ByteArray {

val digester = MessageDigest.getInstance("MD5")

digester.update(this.toByteArray(Charset.defaultCharset()))

return digester.digest()

}

Note that the function name is preceded by the name of the extended class (in this case, String), and that the instance of the extended class is available via this keyword.

Extension functions are the equivalent of Java utility functions. The example function in Java would look like:

public static int toNumber(String instance) {

return Integer.valueOf(instance);

}

The example function must be placed in a Utility class. What that means is that extension functions don’t modify the original extended class, but are a convenient way of writing utility methods.

Feature #5: Null-safety

One of the things you hustle the most in Java is probably NullPointerException. Null-safety is a feature that has been integrated into the Kotlin language and is so implicit you usually won’t have to worry about. The official documentation states that the only possible causes of NullPointerExceptions are:

- An explicit call to throw

NullPointerException. - Using the

!!operator (which I will explain later). - External Java code.

- If the

lateinitproperty is accessed in the constructor before it is initialized, anUninitializedPropertyAccessExceptionwill be thrown.

By default, all variables and properties in Kotlin are considered non-null (unable to hold a null value) if they are not explicitly declared as nullable. As already mentioned, to define a variable to accept a null value, a question mark must be added after the type. For example:

val number: Int? = null

However, note that the following code won’t compile:

val number: Int? = null

number.toString()

This is because the compiler performs null checks. To compile, a null check must be added:

val number: Int? = null

if(number != null) {

number.toString();

}

This code will compile successfully. What Kotlin does in the background, in this case, is that number becomes nun-null (Int instead of Int?) inside the if block.

The null check can be simplified using safe call operator (?.):

val number: Int? = null

number?.toString()

The second line will be executed only if the number is not null. You can even use the famous Elvis operator (?:):

val number Int? = null

val stringNumber = number?.toString() ?: "Number is null"

If the expression on the left of ?: is not null, it is evaluated and returned. Otherwise, the result of the expression on the right is returned. Another neat thing is that you can use throw or return on the right-hand side of the Elvis operator since they are expressions in Kotlin. For example:

fun sendMailToUser(user: User) {

val email = user?.email ?: throw new IllegalArgumentException("User email is null")

//...

}

The !! Operator

If you want a NullPointerException thrown the same way as in Java, you can do that with the !! operator. The following code will throw a NullPointerException:

val number: Int? = null

number!!.toString()

Casting

Casting in done by using an as keyword:

val x: String = y as String

This is considered “Unsafe” casting, as it will throw ClassCastException if the cast is not possible, as Java does. There is a “Safe” cast operator that returns the null value instead of throwing an exception:

val x: String = y as? String

For more details on casting, check the Type Casts and Casts section of the official documentation, and for more details on null safety check the Null-Safety section.

lateinit properties

There is a case in which using lateinit properties can cause an exception similar to NullPointerException. Consider the following class:

class InitTest {

lateinit var s: String;

init {

val len = this.s.length

}

}

This code will compile without warning. However, as soon as an instance of TestClass is created, an UninitializedPropertyAccessException will be thrown because property s is accessed before it is initialized.

Feature #6: Function with()

Function with() is useful and comes with the Kotlin standard library. It can be used to save some typing if you need to access many properties of an object. For example:

with(helloWorldTextView) {

text = "Hello World!"

visibility = View.VISIBLE

}

It receives an object and an extension function as parameters. The code block (in the curly braces) is a lambda expression for the extension function of the object specified as the first parameter.

Feature #7: Operator Overloading

With Kotlin, custom implementations can be provided for a predefined set of operators. To implement an operator, a member function or an extension function with the given name must be provided.

For example, to implement the multiplication operator, a member function or extension function, with the name times(argument), must be provided:

operator fun String.times(b: Int): String {

val buffer = StringBuffer()

for (i in 1..b) {

buffer.append(this)

}

return buffer.toString()

}

The example above shows an implementation of binary * operator on the String. For example, the following expression will assign value “TestTestTestTest” to a newString variable:

val newString = "Test" * 4

Since extension functions can be used, it means the default behavior of the operators for all the objects can be changed. This is a double-edged sword and should be used with caution. For a list of function names for all operators that can be overloaded, check the official documentation.

Another big difference compared to Java are == and != operators. Operator == translates to:

a?.equals(b) ?: b === null

While operator != translates to:

!(a?.equals(b) ?:

What that means, is that using == doesn’t make an identity check as in Java (compare if instances of an object are the same), but behaves the same way as equals() method along with null checks.

To perform identity check, operators === and !== must be used in Kotlin.

Feature #8: Delegated Properties

Certain properties share some common behaviors. For instance:

- Lazy-initialized properties that are initialized upon first access.

- Properties that implement Observable in Observer pattern.

- Properties that are stored in a map instead as separate fields.

To make cases like this easier to implement, Kotlin supports Delegated Properties:

class SomeClass {

var p: String by Delegate()

}

This means that getter and setter functions for the property p are handled by an instance of another class, Delegate.

An example of a delegate for the String property:

class Delegate {

operator fun getValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>): String {

return "$thisRef, thank you for delegating '${property.name}' to me!"

}

operator fun setValue(thisRef: Any?, property: KProperty<*>, value: String) {

println("$value has been assigned to '${property.name} in $thisRef.'")

}

}

The example above prints a message when a property is assigned or read.

Delegates can be created for both mutable (var) and read-only (val) properties.

For a read-only property, getValue method must be implemented. It takes two parameters (taken from the offical documentation):

- receiver - must be the same or a supertype of the property owner (for extension properties, it is the type being extended).

- metadata - must be of type

KProperty<*>or its supertype.

This function must return the same type as property, or its subtype.

For a mutable property, a delegate has to provide additionally a function named setValue that takes the following parameters:

- receiver - same as for

getValue(). - metadata - same as for

getValue(). - new value - must be of the same type as a property or its supertype.

There are a few standard delegates that come with Kotlin that cover the most common situations:

- Lazy

- Observable

- Vetoable

Lazy

Lazy is a standard delegate that takes a lambda expression as a parameter. The lambda expression passed is executed the first time getValue() method is called.

By default, the evaluation of lazy properties is synchronized. If you are not concerned with multi-threading, you can use lazy(LazyThreadSafetyMode.NONE) { … } to get extra performance.

Observable

The Delegates.observable() is for properties that should behave as Observables in Observer pattern. It accepts two parameters, the initial value and a function that has three arguments (property, old value, and new value).

The given lambda expression will be executed every time setValue() method is called:

class User {

var email: String by Delegates.observable("") {

prop, old, new ->

//handle the change from old to new value

}

}

Vetoable

This standard delegate is a special kind of Observable that lets you decide whether a new value assigned to a property will be stored or not. It can be used to check some conditions before assigning a value. As with Delegates.observable(), it accepts two parameters: the initial value, and a function.

The difference is that the function returns a Boolean value. If it returns true, the new value assigned to the property will be stored, or otherwise discarded.

var positiveNumber = Delegates.vetoable(0) {

d, old, new ->

new >= 0

}

The given example will store only positive numbers that are assigned to the property.

For more details, check the official documentation.

Feature #9: Mapping an Object to a Map

A common use case is to store values of the properties inside a map. This often happens in applications that work with RESTful APIs and parses JSON objects. In this case, a map instance can be used as a delegate for a delegated property. An example from the official documentation:

class User(val map: Map<String, Any?>) {

val name: String by map

val age: Int by map

}

In this example, User has a primary constructor that takes a map. The two properties will take the values from the map that are mapped under keys that are equal to property names:

val user = User(mapOf(

"name" to "John Doe",

"age" to 25

))

The name property of the new user instance will be assigned the value of “John Doe” and age property the value 25.

This works for var properties in combination with MutableMap as well:

class MutableUser(val map: MutableMap<String, Any?>) {

var name: String by map

var age: Int by map

}

Feature #10: Collections and Functional Operations

With the support for lambdas in Kotlin, collections can be leveraged to a new level.

First of all, Kotlin distinguishes between mutable and immutable collections. For example, there are two versions of Iterable interface:

- Iterable

- MutableIterable

The same goes for Collection, List, Set and Map interfaces.

For example, this any operation returns true if at least one element matches the given predicate:

val list = listOf(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

assertTrue(list.any { it % 2 == 0 })

For an extensive list of functional operations that can be done on collections, check this blog post.

Conclusion

We have just scratched the surface of what Kotlin offers. For those interested in further reading and learning more, check:

- Antonio Leiva’s Kotlin blog posts and book.

- Official documentation and tutorials from JetBrains.

To sum up, Kotlin offers you the ability to save time when writing native Android applications by using an intuitive and concise syntax. It is still a young programming language, but in my opinion, it is now stable enough to be used for building production apps.

The benefits of using Kotlin:

- Support by Android Studio is seamless and excellent.

- It is easy to convert an existing Java project to Kotlin.

- Java and Kotlin code may coexist in the same project.

- There is no speed overhead in the application.

The downsides:

- Kotlin will add its libraries to the generated

.apk, so the final.apksize will be about 300KB larger. - If abused, operator overloading can lead to unreadable code.

- IDE and Autocomplete behaves a little slower when working with Kotlin than it does with pure Java Android projects.

- Compilation times can be a bit longer.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Ivan Kušt

Zagreb, Croatia

Member since April 14, 2016

About the author

Ivan is a mobile enthusiast who has perfected the development process and architecture of mobile apps.

PREVIOUSLY AT