The Higher Ground – A Guide to Design Ethics

An ethical approach to design is built on questions, not preconceived notions of right and wrong. But what questions should we ask, and how do we classify our answers?

An ethical approach to design is built on questions, not preconceived notions of right and wrong. But what questions should we ask, and how do we classify our answers?

Micah helps businesses craft meaningful connections through branding, illustration, and design.

Expertise

Design impacts humanity. It affects our spaces and places, professions and pastimes, friendships and families.

Design improves lives. It reduces injuries, increases productivity, and makes knowledge more accessible.

But there’s a darker side, a way of using design irresponsibly—even destructively. We’ve seen the statistics and read the studies. We’ve been shocked by the stories and outraged by the investigations. We worry about our privacy, our safety, and our psychological wellbeing. Design can do harm.

As designers, we want our work to help, not hinder. In an effort to protect the people we design for, we invoke labels. We name things “good” or “bad” and let our worldview guide design decisions. Our intentions are good, but our method is myopic. We need a systematic approach to help us examine both our design choices and their underlying motives—an ethical approach.

Design Ethics Crash Course

Ethics is a nuanced field with many branches. But for all its layers, ethics cannot provide moral certainty on every issue. Likewise, no ethical method is able to align all cultures on all matters of morality.

When we talk about ethics and design, we immediately veer into futility if our aim is to establish a universal list of do’s and don’ts. An ethical approach to design is built on questions, not preconceived notions of right and wrong, but we have to know what questions to ask and how to classify our answers. Otherwise, we will be tempted to use ethics to confirm what we already believe and manipulate perception in favor of our design decisions.

To avoid confusion and prevent the misuse of ethics, let’s clarify a handful of important classifications and misconceptions.

What Is Ethics?

Ethics is a system of behavioral standards that help us decide how to act within a specific set of circumstances. When considering an ethical issue, choices are examined through questions that reveal our motives, our awareness of key facts, and how our actions will affect others. Ethical thinking helps us face predicaments like:

- How do we live a good life?

- What are our rights and responsibilities?

- How do we know the difference between right and wrong?

- How do we choose the best action in any given situation?

Common Misconceptions About Ethics

It’s not uncommon for people to appeal to arguments that exist outside of ethics in an attempt to draw ethical conclusions. Such overtures can be highly persuasive, but they may also be misleading.

Science ≠ Ethics

Science provides us with information and data about the observable universe. This information can inform ethical decisionmaking, but it doesn’t tell us why we should act a certain way (a key consideration of ethics). Additionally, scientific or technological possibility doesn’t equal ethical integrity.

A freelance UX designer was hired to improve an underperforming call-to-action in her client’s web app. The designer identified and tested a solution that dramatically improved the CTA’s conversion rate. Based on the statistical improvement alone, does the designer have enough information to determine if her solution is ethical?

Feelings ≠ Ethics

Feelings guide our ethical decisions, but in many cases, they are unreliable and self-focused (whereas ethics is primarily other-focused). Environmental stimuli, cultural expectations, social conditioning, and other factors impact our feelings. It’s even possible to feel that an act is ethical when in reality it is morally reprehensible. We ought to be in tune with our feelings, but feelings aren’t ethics.

A brand design team was hired to rethink a company’s core promise to its customers. After much research and strategizing, the team presented a radical new vision, and the company’s stakeholders were thrilled. Does the stakeholders’ excitement ensure that the new brand promise is ethical?

Cultural Norms ≠ Ethics

Cultural norms promote order, harmony, and cooperation among people groups, but cultures are prone to overlooking their own shortcomings. Cultural blind spots may lead to destructive attitudes and actions toward outsiders. We ought to be sensitive to cultural expectations when facing ethical decisions, but morality is not governed by consensus among a group of people.

A team of UX researchers was sent to a neighborhood to interview a group of people who traced their ancestry and way of life to a common homeland. Over the course of the interviews, the researchers discovered that the members of the community unanimously agreed on a hot-button societal issue and cited a long-standing cultural tradition as their reason why. Does the cultural tradition (or its widespread acceptance) make the community members’ viewpoint ethically sound?

Religion ≠ Ethics

Religious institutions promote good morals and encourage followers to weigh the ethical implications of their actions, but not everyone practices a religion. Religious traditions and teachings may also be misinterpreted over time, leading adherents to ascribe to a list of rigid rules that result in unethical behavior.

Several members of a small web design consultancy shared common religious beliefs. They genuinely tried to do the right thing and sometimes referenced the teachings of their faith when faced with difficult design decisions. Does the team’s union of design and religion guarantee that their actions are ethical?

Legality ≠ Ethics

Laws are meant to maintain peace and protect citizens. In an ideal world, the laws that are in place would lead to ethical behavior, but in the real world, laws can be corrupted and circumvented. It’s possible for a legally permissible action to be morally unscrupulous.

A corporate design team for a popular SaaS platform was tasked by upper management to build and introduce a groundbreaking tool. The tool had features that raised concerns within the team, but after some investigation, everything was found to be perfectly legal. Does the legality of the features also assure that they are ethically uncompromised?

Core Ethical Approaches

There are a number of ethical approaches, but each has a different standard by which to examine actions. Unfortunately, the standards of differing ethical approaches don’t always align. Examination by one approach may tell us an action is good. Further examination by a different approach may tell us that the very same action is problematic. Because of this variance, it can be helpful to look at ethical decisions through a handful of lenses.

The Utilitarian Approach

Greek philosopher Epicurus sowed the seeds of utilitarianism when he taught that the best life was the one that most elevated pleasure and diminished pain. Today, the utilitarian approach teaches that the best action is the one that yields the greatest good and least harm for all involved.

The utilitarian approach leads us to look beyond use cases and personas and causes us to examine the wider impact of our design decisions. It also prompts us to consider how "the greatest good and least harm" relates to different [design problems](https://www.toptal.com/designers/product-design/design-problem-statement).

The Rights Approach

The rights approach is founded on the belief that all humans possess a right to dignity and respect. Therefore, the best action is the one that most completely preserves the rights and honor of all affected.

It’s possible to generate design solutions that don’t respect the dignity of end users—a common side effect of the "designer knows best" mentality. The rights approach reminds us that we’re not just solving problems; we’re aiming to improve the quality of life of our fellowmen.

The Justice Approach

Originally, the justice approach taught that people of equal standing or circumstances should be treated equally. Over the years, it has evolved and now states that an ethical choice is one that results in fair and equal treatment for all involved. The justice approach does allow for people to be treated differently, so long as there is a morally justifiable reason for doing so.

The justice approach encourages us to question if our designs are partial to the needs of one user over another. (And if so, why?)

The Virtue Approach

With its Aristotelian roots, the virtue approach emphasizes the whole of a person’s life as opposed to individual decisions. The aim is attaining virtues and living as the most excellent and appropriate version of oneself. All actions are weighed by how well they contribute to (or detract from) this ideal.

The virtue approach invites us to think about our design careers comprehensively. It implores us to step away from judging individual design decisions so that we may ask whether or not our actions are leading us to be the kind of designers we aspire to be.

Should Designers Take an Oath?

There’s no debate. Design, especially digital product design, continually changes the way we communicate, spend money, and do business. Many changes are positive, but others exploit vulnerable members of society. This isn’t new.

Technology advances. Technology is abused. Technology adjusts—but not on its own. Designers aren’t lawmakers or regulators, but we are agents of change. It’s up to us to work conscientiously and ethically, but how can we be sure that our good intentions aren’t misguided?

Do we need an ethical code? An oath to pledge, sign, and hang on our walls? Maybe, but codes and oaths tend to become static. They give us something to aspire to, an ideal to reflect on, but they aren’t something we recall in the daily design grind or something we recite with budgets at risk and deadlines looming. Codes and oaths won’t make us ethical designers.

Instead, we need a framework built on meaningful questions, a framework that elevates decisions over conclusions of right and wrong. Why? Decisions are intentional. They foster an ongoing sense of responsibility for the impact of choices made. Decisions are case by case. They help us avoid the false security of preconceived labels and arguments that aren’t founded on ethics.

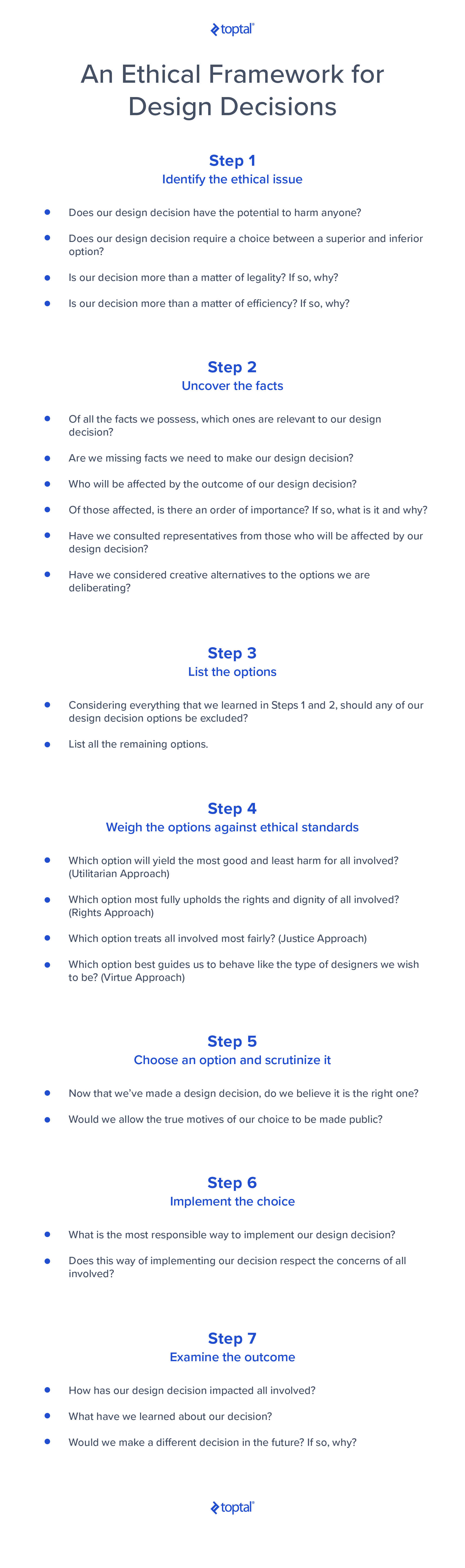

How to Use an Ethical Framework for Design Decisions

During the early phases of every design project, there are hundreds of decisions made on instinct. Training and past experiences guide our initial efforts and help us bring order to the nebulous cloud of requests, facts, and ideas hovering about our heads. As we cycle through the design process and concepts begin to take shape, our instincts provide less certainty, especially when it comes to difficult design decisions.

When a decision of an ethical nature arises during the design process, put it through the paces of the framework. Each step has targeted questions that peel away pretense to expose important facts and underlying motives. At the end of the framework, there’s no scoring system or list of recommendations. That’s intentional. The framework can’t think or choose, but designers can. It’s on us to own our actions.

Download a PDF version of the Ethical Framework for Design Decisions here.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is ethical and responsible design?

Ethical and responsible design is determined case by case. Each design problem and solution must be weighed with specific ethical questions that reveal motives and predict how design decisions will affect others. Context matters. A design feature that is ethical in one scenario may be unethical in another.

What is an ethical designer?

Ethical designers think about design problems and solutions from the big picture. They don’t just ask if their design work is legal, efficient, or cost-effective; they ask how their decisions will affect others. They also question the motives of their decisions and take responsibility for the choices they make.

Why is it important to understand ethics and how it relates to product design?

Ethics is concerned with how our choices and actions affect others. It forces us to think beyond our own good and consider the good of others. It’s important for designers to understand how ethics relates to product design because products are designed for people, and product design impacts the way people live.

What is an ethical design dilemma?

An ethical design dilemma occurs when designers are faced with a decision that will significantly affect the lives of others. While it’s true that most or all design decisions affect other people, some are of greater impact. In many cases, the dilemma is a choice between two options that appear equally beneficial.

What is an ethical concept?

An ethical concept is a way of determining the morality of an action within its context. For instance, the ethical concept of the utilitarian approach teaches that an ethical action is one that brings about the most good and least harm for all who are affected.

Micah Bowers

Vancouver, WA, United States

Member since January 3, 2016

About the author

Micah helps businesses craft meaningful connections through branding, illustration, and design.