Why Are Emerging Market Currencies Volatile?

The attention on international payments tends to center around innovations appearing in the developed world. But what about developing countries?

This article addresses what contributes to volatility and illiquidity in emerging market currencies, and how they can stabilize to become more flexible.

The attention on international payments tends to center around innovations appearing in the developed world. But what about developing countries?

This article addresses what contributes to volatility and illiquidity in emerging market currencies, and how they can stabilize to become more flexible.

Pedro is an expert in FP&A with extensive experience across emerging markets, most notably as a CFO of a $5Bn revenue business.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Executive Summary

Emerging market currencies are volatile and illiquid, which restricts financial freedom

- Innovation and attention in international money transfer tend to focus on remittances from developed to developing countries. The often ignored "reverse remittances" that go in the opposite direction receive much less.

- Emerging market citizens experience restrictions in their financial management as a result of wide currency spreads, high commissions, long delays, and red tape bureaucracy.

- Volatility, a measure of standard deviation for asset price moves, is high for emerging market currencies and their markets are illiquid. These both contribute to restrictions that consumers and businesses endure.

What contributes to the volatility and illiquidity?

- Economic policy in developed markets can inadvertently spill over and influence the economies of emerging markets in drastic ways. The lack of clout that relatively smaller markets have versus the Federal Reserve or ECB means that actions such as quantitative easing cause irregular inflows into emerging market currencies.

- $7 trillion flowed into emerging economies as a result of Federal Reserve QE initiatives post-2008.

- Emerging market economies are dominated by commodity export industries. The prices of commodities are almost perfectly correlated to emerging market currency prices, which brings inflationary boom periods and painful bust cycles.

- Government regulation, such as capital controls, intend to stabilize economies through restricting investment inflows and outflows. In emerging markets, if this is too severe or erratic, it can harm competition and deter investment. It can also encourage black markets, which further undermine faith in economies.

How can emerging market currencies be stabilized?

- Removing a reliance on commodities allows a country to diversify its economy and prepare better for economic shocks. In addition, investing commodity proceeds into diversification projects, or owning more of the value chain of a commodity’s production cycle, can help to breed sustainability.

- Dollarization is a quick fix for an economy. It involves a country discarding its "soft" currency and switching to a “hard currency” as legal tender. It can immediately abolish inflationary pressures, but removes the nation’s rights to sending interest rates.

- Currency union blocs can also bring together a more diversified and liquid economy for a group of nations under one currency, building clout and stability.

- Use of cryptocurrencies by emerging market consumers can give them more liberation to manage their personal finances. A true long-term and sustainable success from this movement would be for countries themselves to introduce their own cryptocurrencies and digitize their economies.

I enjoyed reading Mauro Romaldini’s recent article about international money transfer; we are clearly experiencing exciting times for innovation in this sector. But it made me think about the often ignored other side of the remittances coin: what about sending money from developing countries to developed ones? I am Brazilian, I live in South Africa, and I will be moving to Switzerland soon to study. Sending money abroad for me is far harder, uncertain, and expensive than just opening an app and pressing send. Why is this the case for senders of “reverse remittances”?

The financial management issues that I face as a citizen from an emerging market country are broadly the following:

- Wide bid/ask spreads when converting currency

- High commissions for sending money

- Long delays and processing times

- Red tape, quotas, and compliance requirements

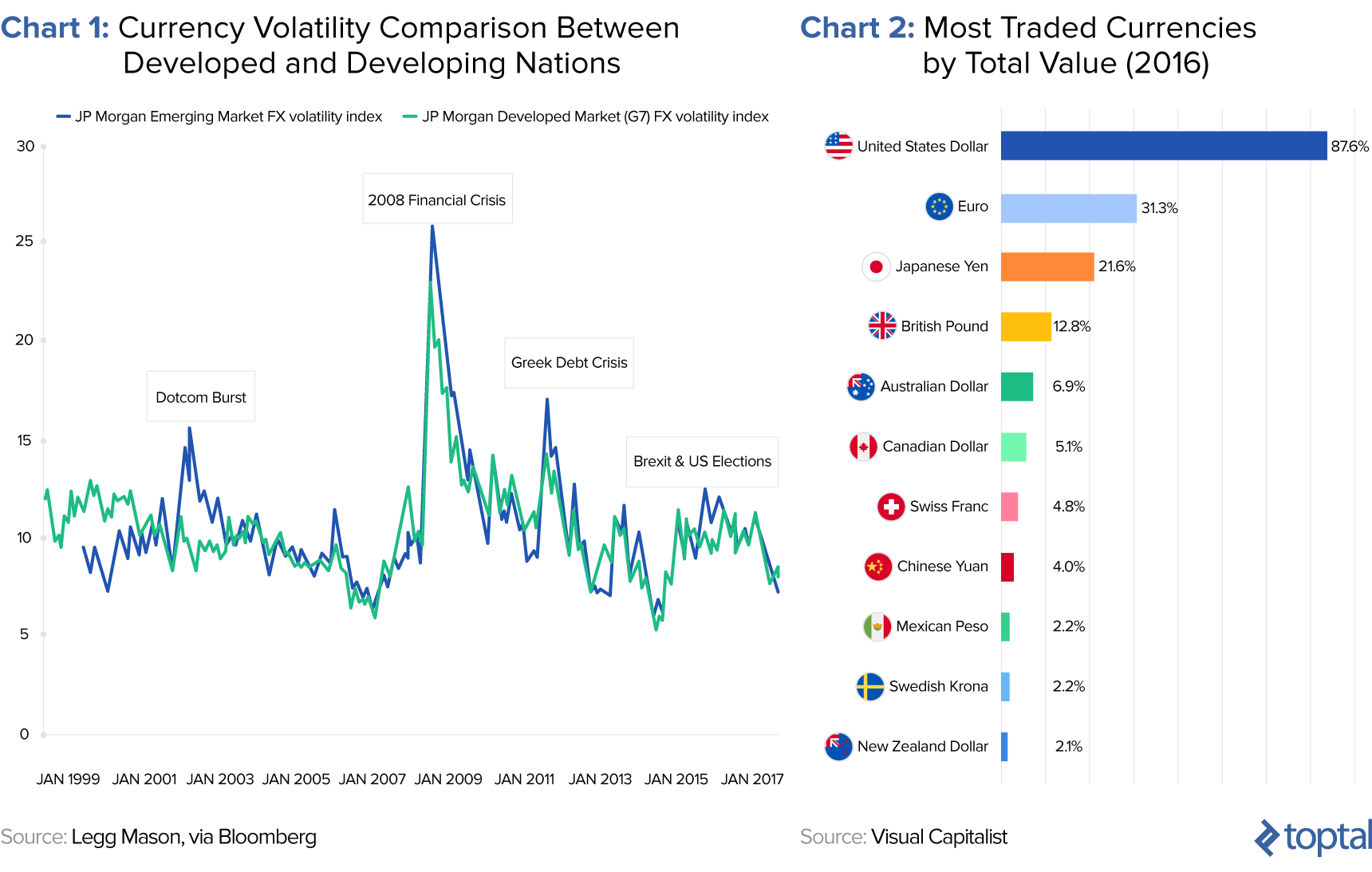

Developing countries have volatile and illiquid markets, across the debt, equity and currency spectrum. Charts 1 and 2 below demonstrates this for emerging market currencies, whereby volatility has more variance and trading volume is largely consigned to G10 currencies.

I believe though that these characteristics are end results of situations that manifest from economic decisions taken in both developing and emerging economies. In this article, I want to address what contributes to emerging market volatility and illiquidity, and their implications upon the financial freedom of citizens and businesses. In addition to this, I will make some suggestions about how they can be solved.

Developed Markets Cough, Emerging Markets Catch a Cold

Currencies are divided into hard and soft types, the former being seen as reliable, widely accepted, and a store of financial value. There is no defined list of them, but the more developed a country is, the more it’s assumed to be one that holds a “hard currency.” That’s why international online shops sometimes list prices in US Dollar or Euro, or when you go on an exotic holiday, certain services are priced in a non-domestic currency. International trade also gets priced in hard currencies. India, for example is the second most populous country on Earth, yet as Chart 2 shows, the Rupee is not traded en masse.

The level of a currency relative to another has ramifications on a country’s ability to import and export. A weak currency allows it to export more through increased competitiveness, but it then results in the importation of goods becoming more expensive. As such, the exchange rate is often a core metric for governments and central banks to focus on to drive their economies. Pegging is a direct way to influence a currency, but often tangential regulatory rules or rhetoric can suffice just as effectively.

My argument here is that due to their lack of relative economic size, emerging market currencies suffer from the indirect spillover effects of interventions made by developed economies.

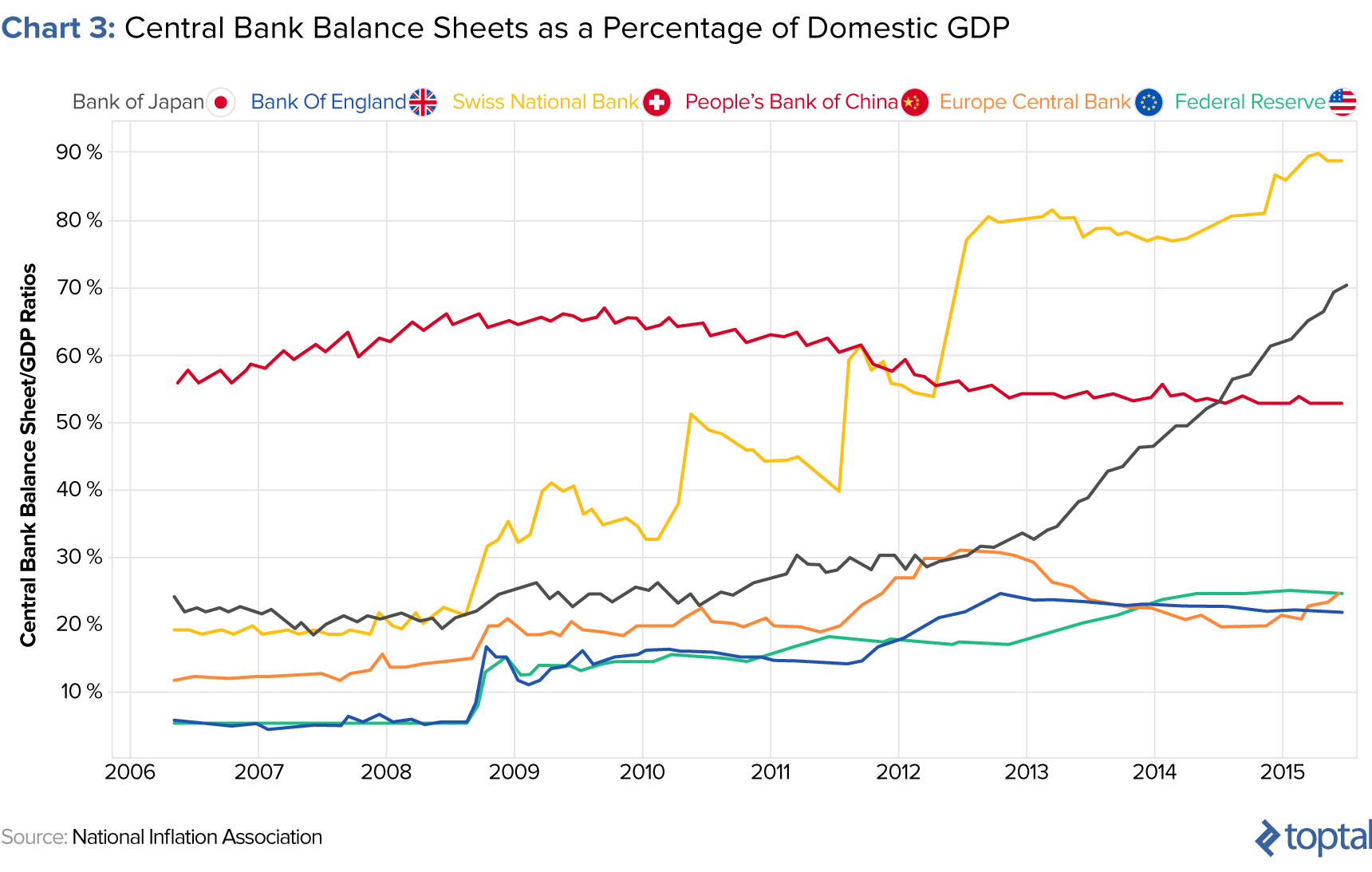

After the 2008 Financial Crisis, the economies of many western nations began implementing programs called quantitative easing (QE), which were intended to stabilize their economies via their central banks buying debt assets from banks. This allowed banks to shift illiquid (and, at times, overvalued) debt off their balance sheets for liquid cash with the intended effect of them then being able to lend the money to stimulate the economy. The effect of this was that it severely bulged the balance sheets of central banks relative to their economies’ GDP.

For developed market investors, this created issues, as the QE programs brought down bond yields through their demand increasing prices. Where would they invest now to find yield? A financial analyst would, of course, recommend higher yield emerging markets, the result of which caused demand for emerging market currencies to increase. It is estimated that $7 trillion of Federal Reserve QE dollars flowed into emerging markets post 2008. These inflows came with two potentially negative externalities for governments; leave them unchecked and their currency would appreciate and harm exports, or print money to depreciate the currency and watch a borrowing bubble emerge. Brazil is one such country where the effects of QE have severely affected the domestic economy.

The sheer power of the developed market central banks is a force that developing equivalents cannot counteract. It creates abnormal inflows into their currencies, inflows that in a rational market may not happen. Because these inflows are typically in institutional hot money form (i.e., funds buying securities in the secondary market) and not usually attached to long term projects, the money can just as quickly leave again and leave a long-term mess behind it.

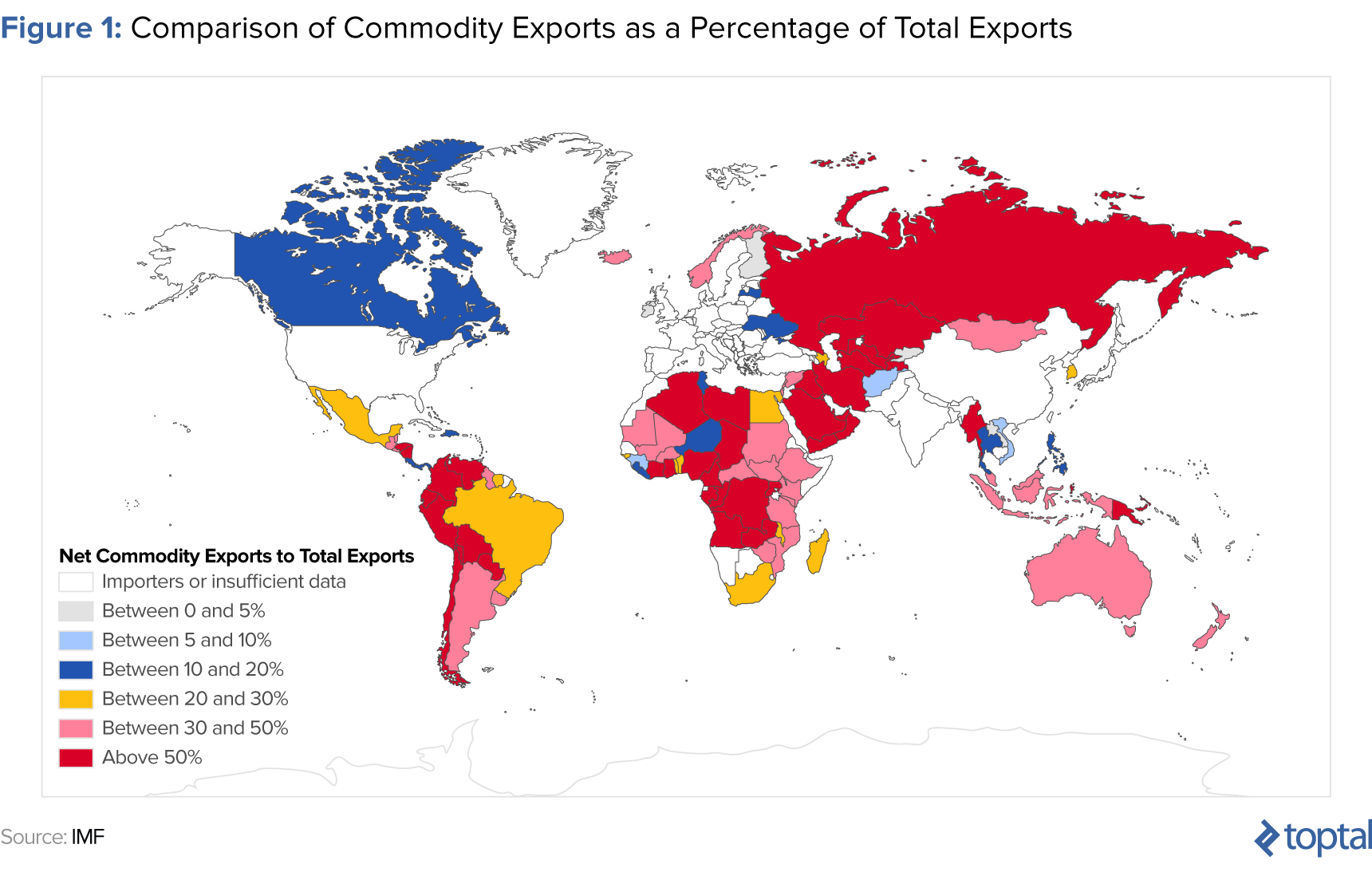

Commodities

Trade between countries can come in the form of services, products, or commodities. Without going too much into macroeconomics, comparative advantage dictates that product and service trade is more difficult to succeed in than commodities—coal is the same, irrespective of where it is extracted. Thus, trading in commodities tends to be the easiest, quickest, and potentially most lucrative route for emerging market countries to export and generate GDP. Typically, countries are bequeathed with rare natural resources, making them a natural component of an export base, but often due to their underdeveloped nature, selling commodities is the only option for trade.

Aside from notable exceptions such as Canada and Australia, Figure 1 below demonstrates the dominance of exports within the economies of developing nations.

The effect of this dominance is that emerging market economies are intrinsically linked to the performance of commodity prices. This creates two extremes, a phenomenon known as the Dutch Disease:

- When commodity prices rise, the currency of the exporter rises and they import more. Other domestic exports suffer from uncompetitive pricing and the country in effect “doubles-down” on commodity success.

- When commodity prices fall, the local currency falls and budget deficits quickly rise and there is no export industry to fall back on.

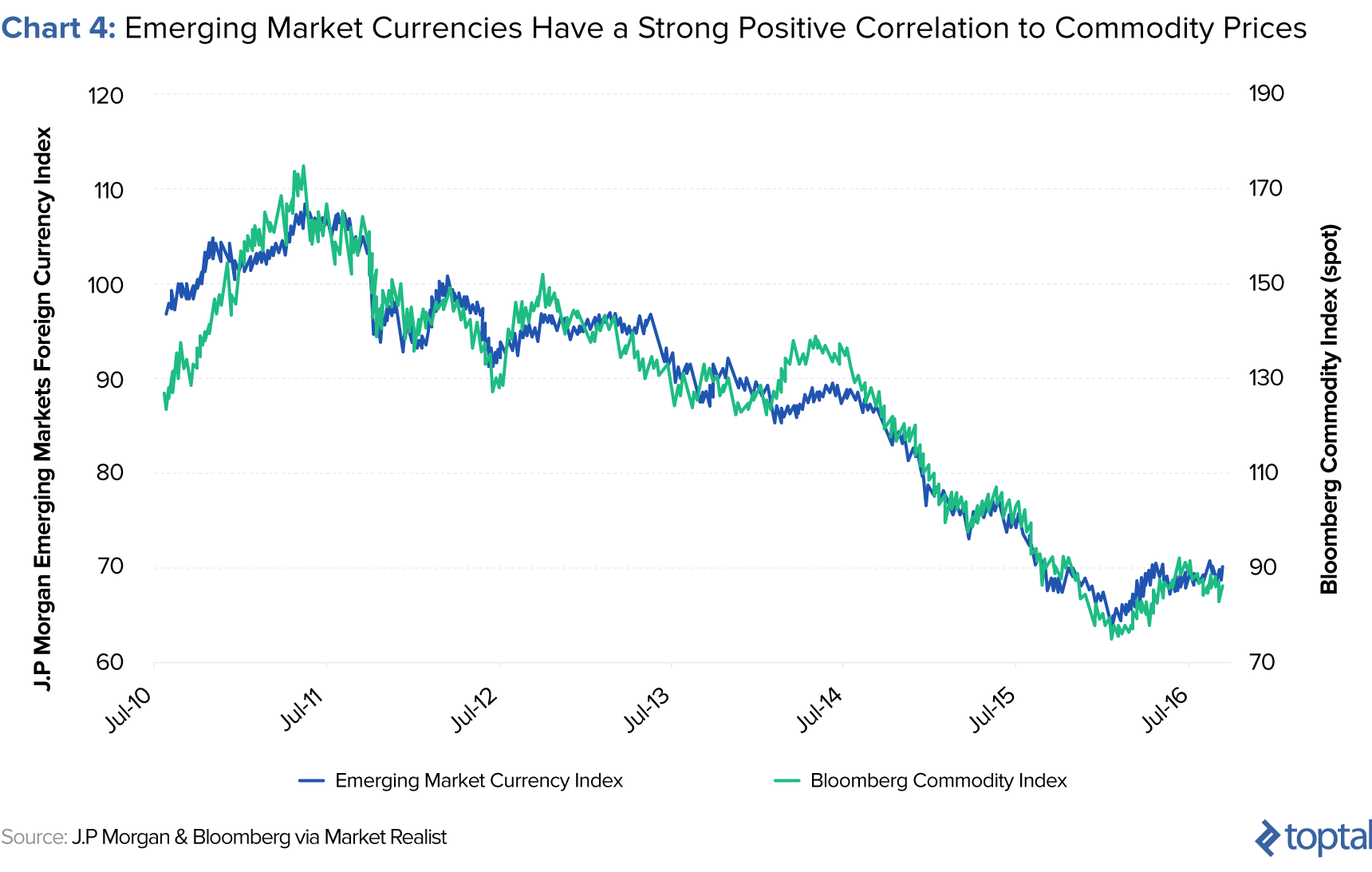

The culmination of this is that emerging market currencies are seen as proxies to the price of commodities. Chart 4 below tracks the six-year performance of a commodity index versus a basket of emerging market currencies; as it shows, they are almost perfectly correlated.

This link means that governments and central banks in emerging markets have a diminished control over their currency—the global commodity markets largely dictate their fortunes. Because of this, currency volatility in emerging markets is high, as its performance is tied to macroeconomic and geopolitical concerns on a global basis. Market makers offer less liquidity and wider bid/ask spreads in such currencies, as risk mitigants, due to reduced faith in developing countries’ abilities to stabilize currencies via domestic fiscal and monetary measures.

OPEC is a body that exists to provide more stability to emerging market oil producing nations through managing their collective quotas to influence the price of oil. However, as can be seen with the emergence of shale oil, the effect of OPEC may diminish over time due to factors, such as shale innovation, far beyond its control.

Regulation

Capital Controls

In light of their fragile economies and currencies, the governments of emerging economies have continuously regulated capital movements via market intervention. These restrictions prevent unrestricted movement of money in and out of countries, with the intended goal that they prevent currency volatility and assorted inflationary swings. There are four broad types of capital controls:

- Minimum stay requirements: Lock-in periods for money to stay in the country

- Limitations: Quotas on inflows/outflows

- Caps on asset sales/ownership: Limitation of investment into certain strategic assets

- Limits on currency trading

One of the most popular and easiest implementations of this is via taxes and tariffs, for example, on credit card purchases in foreign currencies. Restricting investment into strategic areas such as banking also maintains local monopolies under the auspices of preventing reckless competition, but the negatives from this are that innovation and service levels are diminished. I argue though that capital controls such as these can be applied overzealously, and their effects can add to the instability of emerging market currencies and discourage investment.

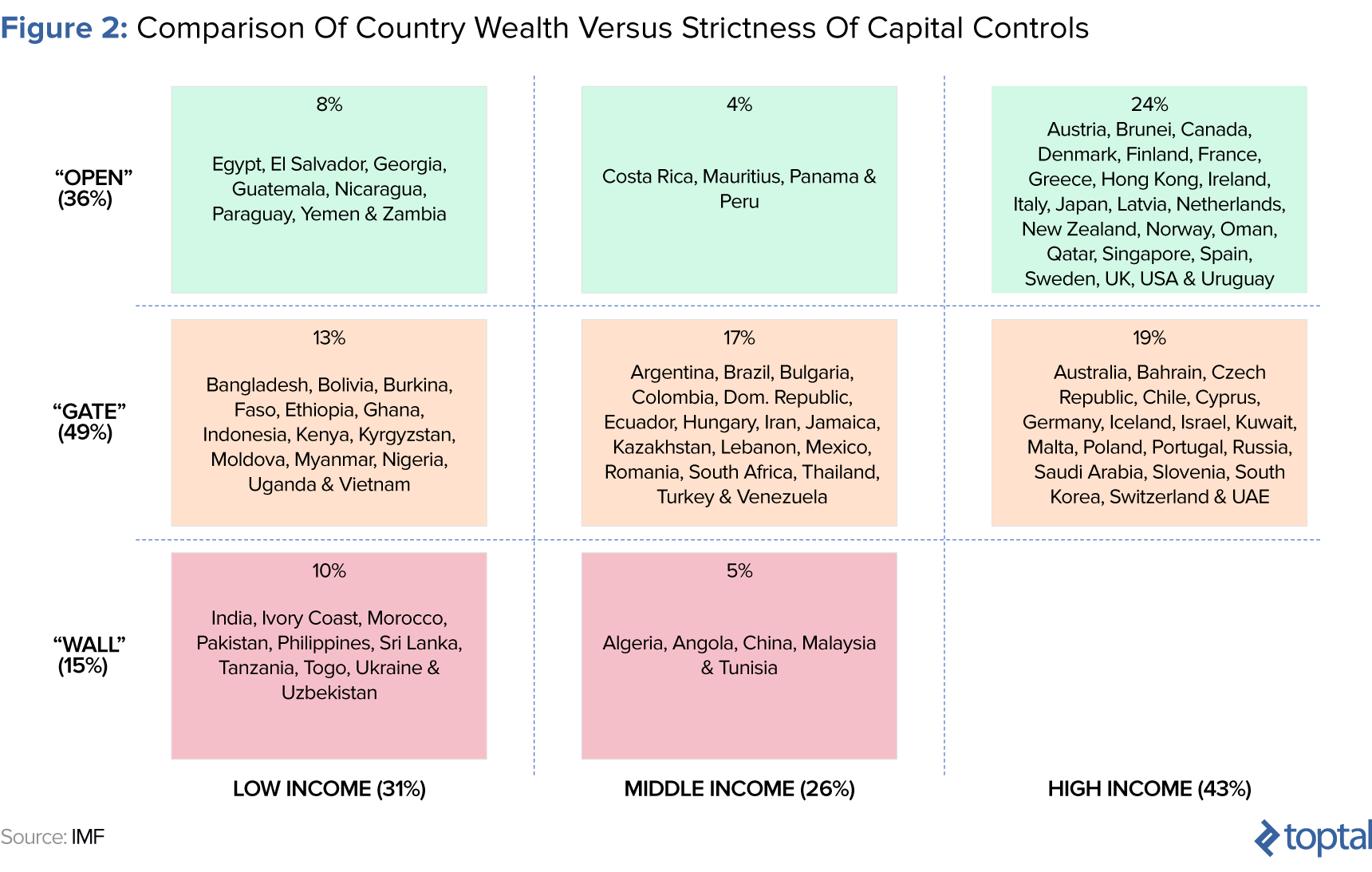

Professor Michael W. Klein classifies countries into three buckets by their use of capital controls:

- Walled: Long-term capital control measures

- Gated: Systems in place to be turned on/off episodically

- Open: No system of control

Figure 2 below shows a 2012 classification of these by the relative wealth of countries.

The consensus shows that developed nations deploy “open” policies, while mid-to-low income nations use capital controls through “gates” and “walls”. Klein’s study, though, noted the popularity and ineffectiveness of gated systems, where episodic control is exercised during times of economic stress. Despite these systems offering more liberation than a pure walled system, their sporadic use makes them easy to evade:

Episodic controls are likely to be less efficacious than long-standing controls for a number of reasons. Evasion is easier in a country that already has experience in international capital markets than in a country that does not have this experience. Countries with long-standing controls are likely to have incurred the sunk costs required to establish an infrastructure of surveillance, reporting and enforcement that makes those controls more effective.

Because gated capital control policies are often deployed as fire-fighting mechanisms, they can be ill-thought-out and easy to evade for some. When investors see a country with gated measures, they get scared. They want to invest in a country that is consistent, one that doesn’t change the rules and allows them to withdraw proceeds easily. The fear of gates drives insecurity up, which is why currency volatility will spike during tense moments when it’s expected that they will come into force.

Black Markets

Aside from discouraging investment, capital controls can create parallel markets, which further undermine faith in an economy. Usually as a result of restrictions on foreign currency or unrealistic pegs, black markets are created. In shifting to these, market participants bypass formal institutions, slowing down the velocity of money in the formal economy.

Because the black market exchange rate will often reflect the true purchasing power parity rate of the currency, foreign investors are further discouraged from investing in the country through expensive official channels. Some examples of the overvaluation of official exchange rates versus their black market equivalents shows this disconnect (at December 2017):

| Currency | Official Rate (to 1 USD) | Black Market Rate | Overvaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angolan Kwanza | 165 [source] | 410 [source] | 148% |

| Nigerian Naira | 305 [source] | 362.5 [source] | 19% |

| Venezuelan Bolivar | 10-3,340 [source] | >100,000 [source] | 2,894% |

How Can This Situation Improve?

An obvious way for barriers of international payments and trade to be removed in developing countries is for them to develop economically. South Korea, for example, was a poor country in the 1960s with a GDP per capita of below $100; as of 2017, it is now considerably wealthier and this same figure has risen to $27,538. This growth has corresponded with the liberalization of its financial markets and the nation now stands at 23rd in the world for economic freedom.

In this section I will describe some specific interventions that can be made to achieve this.

Remove Reliance on Commodities and Diversify the Economy

The first suggestion is the most obvious but hardest to implement. Creating a diversified economy allows for “hedged” economic performance to coexist. For example, If a country manufactures finished goods from its extracted commodity, a lower commodity price will shock and subsequently benefit the manufacturing industry from cheaper inputs.

The extraction process of commodities can tend to follow a smash and grab mentality, where rents are secured, but panic ensues when prices drop or reserves are exhausted. One such measure to build an economy up from commodities is to set up a sovereign wealth fund. When you see Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds invest in indoor ski slopes, or sports teams, they’re not impulse buys—they show intent to help the economy diversify.

Another measure is to seek more collaboration with international mining firms for skill transfers. Despite holding the world’s largest potential deposits of lithium, Bolivia has been stubbornly refusing overtures from international miners to extract them, due to its own desire to participate in the industry and produce finished goods itself. Seeking a middle ground of partnering up will allow for technical knowledge to disseminate quicker and let the national economy learn from the process.

Dollarization

A silver bullet solution is to “dollarize” the economy, replacing local tender with a hard currency issued by another country. As per the name, this is most common with the US Dollar, but in Europe, both Montenegro and Kosovo employ the Euro as official legal tender despite not being in the Eurozone, nor the EU itself.

Currency volatility will naturally subside under dollarization scenarios. However it’s not a natural prelude towards easy payments and movement of capital. A dollarized country also forgoes its monetary policy tools, leaving tax as the only major lever that a government can pull to direct the economy.

Currency Unions

The first cries against a currency union would be similar to those against dollarization: The domestic country would be “outsourcing” monetary policy mechanisms to a foreign body. But as benefits of the Euro have shown, it can install a culture of best practice and actually having oversight on a consensus-led basis by a central body may ensure that better decisions are made.

The West African and Central African Francs are rare examples of such unions in developing markets. Derived from a historic colonial agreement, they are guaranteed to be converted by the French government to the Euro at a set rate, which is an advantageous quirk that other currency unions will not have. Moves to expand currency unions in Africa, via the Eco, could provide the clout needed for emerging market currencies to stabilize, gain more liquidity and open up the economies of the respective nations.

Cryptocurrencies

For consumers, storing wealth and making international payments via cryptocurrencies would be an easy way for them to bypass the idiosyncrasy of their country’s currency. They counteract the bureaucracy, bank monopolies, and opaque regulations that restrict them. Of course, in doing this, consumers switch their currency volatility to that of a cryptocurrency, which arguably can be as hard to predict as their own fiat currency.

Aside from popular cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, there are specific altcoins designed to offer a hard price commitment to a fiat currency, in a similar manner to a traditional currency peg. This allows users to purchase a coin and redeem it 1:1 with a hard currency like USD. The decentralized ledger system may provide more faith to an investor to store their value here, as opposed to a domestic banking system. These pegged cryptocurrencies are by no means perfect; some that have launched have fared poorly. The one coin that has gained traction, Tether, has also had problems of its own.

Both of these solutions are bypass measures and do not address the fundamental issues of the underlying economy. If consumers did just reject their domestic monetary systems en masse, their economies would suffer through an assortment of reasons like lower tax receipts and banks failing.

Cryptocurrencies, though, do offer a potential solution for emerging economies to digitalize their markets. There have been moves by some countries to adopt digital currencies—Tunisia, Senegal, and Ecuador, to name a couple. While it’s early days to say how effective these could be, or whether they are just PR noises, these moves do show promise. A distributed ledger would be one means to stop inflationary money printing by a central bank that answers to nobody; in addition, electronic money is also far easier and cheaper to transact for consumers.

A Path to Financial Flexibility for Emerging Economies?

Lack of clout, undiversified economies, and restrictive regulation are the contributing factors that make emerging market currencies more volatile than their developed counterparts. The former two contribute to the latter’s existence, which is what affects people like myself the most in terms of restricting citizens’ financial freedom. I am not arguing that emerging market countries should prioritize making it easier for people like me to buy things on Amazon.com, though—instead, that perhaps a more progressive approach could encourage more sustainable foreign investment and economic development, with the spillover effects granting more financial freedom to consumers.

With regards to the solutions, I would be fascinated to see an emerging market country introduce a cryptocurrency and attempt to roll out a digital financial economy. I will be keeping an eye on developments here, because it could usher in a completely new concept of macroeconomic financial management

Disclosure: The views expressed in the article are purely those of the author. The author has not received and will not receive direct or indirect compensation in exchange for expressing specific recommendations or views in this report. Research should not be used or relied upon as investment advice.

Understanding the basics

What is meant by currency volatility?

Currency volatility is a statistical technique deployed within the financial industry to measure standard deviation (or variance) of asset returns. It shows the magnitude of positive and/or negative price changes.

What is the most volatile currency?

As of December 2017, the South African Rand and Turkish Lira are widely viewed as the most volatile currencies in the world. In addition, the Russian Ruble, Mexican Peso, and Colombian Peso all have current and historic reputations for high volatility.

What is an emerging market?

Emerging market countries are nations that are experiencing rapid industrialization and escalating economic growth. Markets can be classified according to such levels of economic development, or conversely by the level of market access offered to foreign investors.

Pedro Kniphoff

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Member since August 18, 2017

About the author

Pedro is an expert in FP&A with extensive experience across emerging markets, most notably as a CFO of a $5Bn revenue business.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT