Pricing Strategies for Success: A Practical Guide

Pricing strategy is one of the most important functions that any business engages in. Prices are a foundational element of a company’s revenues—If managed carefully, they can generate high profits and consequently cash. But setting prices appropriately is tricky, and when mistakes are made, companies suffer.

In this article, Toptal Finance Expert Dalibor Pajic draws on his 15+ year career in corporate finance to outline seven practical examples of when pricing strategy plays a crucial role, with the aim of illustrating how pricing decisions can be approached in different situations. Pending

Pricing strategy is one of the most important functions that any business engages in. Prices are a foundational element of a company’s revenues—If managed carefully, they can generate high profits and consequently cash. But setting prices appropriately is tricky, and when mistakes are made, companies suffer.

In this article, Toptal Finance Expert Dalibor Pajic draws on his 15+ year career in corporate finance to outline seven practical examples of when pricing strategy plays a crucial role, with the aim of illustrating how pricing decisions can be approached in different situations. Pending

Dalibor is a CFO with over 15 years of experience in corporate finance, investment management, pricing management, and business development.

PREVIOUSLY AT

Executive Summary

Pricing strategy: A powerful tool to generate profit and cash

- Fundamentally, there are two generic pricing strategies:

- Based on cost calculation and adding a markup (cost plus pricing)

- Maximum possible price defined by the product price on the market and charged by the competition (competitive pricing)

- In the first approach, we calculate costs, allocate them to a single product, and then define the markup.

- In the second approach, we start from the market price of the same (or similar) product and work backwards to costs.

Seven practical examples of situations when pricing plays a crucial role

- Maintaining business performance at a targeted level

- Entry into a new market

- As a negotiating tool/target

- Launching a new product

- When capacity utilization is very low

- Private label products

- Internal pricing between profit centers

Pricing strategy is one of the most important functions that any business engages in. Prices are a foundational element of a company’s revenues—if managed carefully, they can generate high profits and consequently cash. Alternatively, if managed incorrectly, companies can suffer, either because low pricing fails to cover costs effectively or because excessively high prices cannibalize sales volumes.

Setting prices appropriately is difficult. Over my 15+ year career in corporate finance, with a particular focus on industrial production, agriculture, and the FMCG industry, I have encountered multiple examples of situations in which poor pricing decisions severely hampered a business’ performance. I wrote this post to share some of the learnings I have gathered, along with several specific pricing strategy situations I have faced. I will draw extensively on my experience as a CFO for two companies in the FMCG sector. Both companies faced active and dynamic markets, with strong competition (domestic and imports) as well as multiple distribution channels (retail chains, traditional shops, distributors, exports, etc). Due to data confidentiality, I will not present real figures, but the examples I set out reflect reality as closely as possible.

Pricing Strategy Basics: A Powerful Tool to Generate Profit and Cash

Fundamentally, there are two generic pricing strategies:

- Based on cost calculation and adding a markup (cost plus pricing)

- Maximum possible price defined by the product price on the market and charged by the competition (competitive pricing)

In the first approach, we calculate costs, allocate them to a single product, and then define the markup. The level of costs allocated to a specific product depends on the current situation of the company (current profitability, capacity usage, etc.). Markups can be defined according to different targets; for example, targeted gross margin, benchmark industry gross margins, etc.

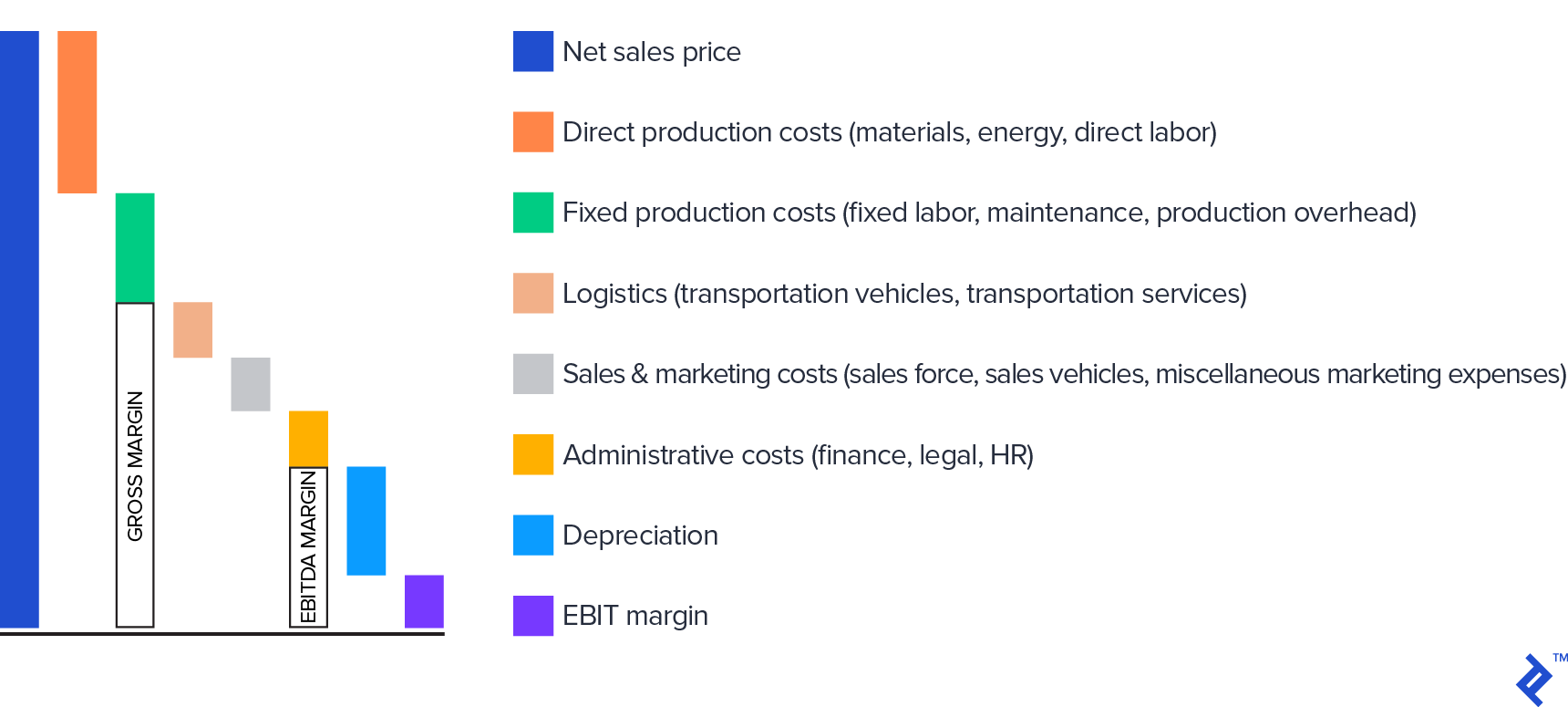

For the purposes of analysis, costs will be categorized into different levels. These levels are presented graphically below.

In principle, the goal should always be to cover costs and reach a positive EBIT margin, but in practice, there are situations when one may be willing to only cover certain costs (I’ll run through some examples later in the article).

In the second approach, we start from the market price of the same (or similar) product and work backward to costs. In this way, we simulate whether with the current market price we can cover all targeted costs and reach our targeted markup. This approach is often used when market competition is strong and when a single player can’t impact the overall market price (such as in FMCG, travel services etc).

N.B. In very rare situations, prices can be regulated by the government in order to protect the population from the high prices of certain basic goods (such as power, public transportation, or communal services).

Seven Examples of Pricing Strategies in Action

To illustrate the importance—and power—of pricing decisions, in this section, I’m going to run through seven practical examples of situations in which pricing is an important tool and one that should be handled with care. As mentioned, these examples all draw heavily from real life situations I have faced throughout my career, and although they have been stylized for the sake of illustration and confidentiality of the numbers, they represent reality as closely as possible.

Pricing Strategy No. 1: Maintaining Business Performance at a Targeted Level

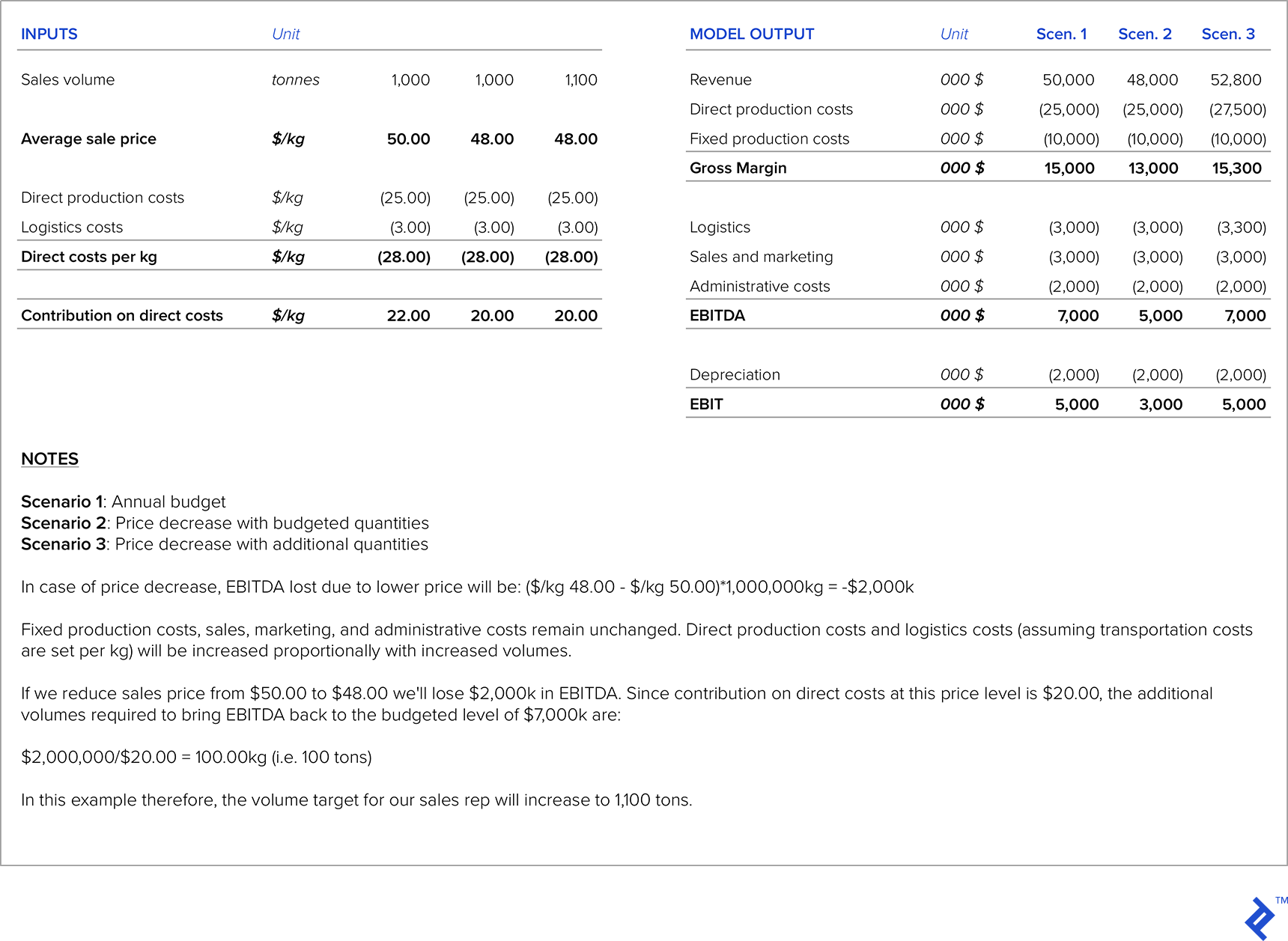

In my career, I have faced situations where a target was mandated by headquarters (e.g., targeted EBITDA) and everyone in the organization works toward this particular target. What often happens is that the sales force will push for price reductions in order to increase volumes, but in these situations, one has to be careful to ensure that the extra sales gained from lower pricing is enough to compensate for lower margin levels; otherwise, EBITDA targets are missed (and HQ is unhappy).

To tackle this issue, I developed a model that, for each product, calculated the price sensitivity relative to the targeted EBITDA. The model, therefore, indicated how much volumes had to increase by for each price reduction level in order to maintain EBITDA margins. It was then used as a guide for the sales force in negotiations with customers.

The figure below presents an example of such a calculation. Let’s assume that in the annual budget we assumed a price of $50.00/kg for the particular product in question. After negotiations with the customer, our sales representative is proposing to reduce the sales price to $48.00/kg. As the initial budgeted quantity was 1,000 tonnes, we have to calculate the additional quantities to be sold in order to keep EBITDA at the budgeted level.

Pricing Strategy No. 2: Entry into a New Market

When a company is planning to enter a new market, there are several benchmarks that can be used to define price.

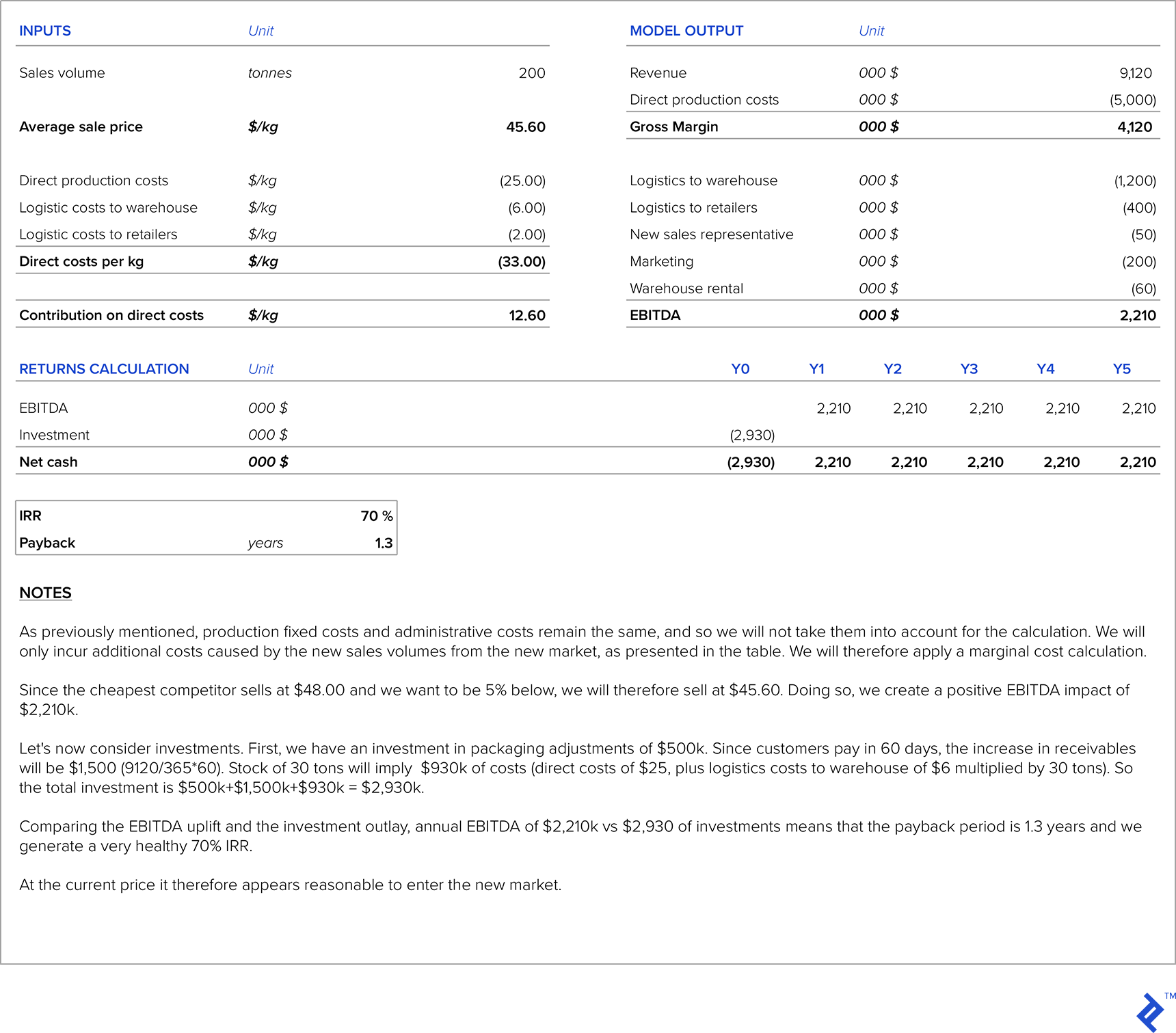

On the cost side, we have direct production costs, additional costs due to sales in the new market (new market research, fees of the local distributors, additional sales force staff for the new market, transportation, etc.), production fixed costs, administrative costs, and depreciation (which usually remains at the same level). We may also incur some investments to adapt our product to the needs of the new market or to increase production capacity. The standard approach to set prices would be to employ a cost plus markup approach, so we’ll run through an illustrative example and then compare it with the market price of the new market. We should then calculate the payback period of the investment needed for the new market.

For our illustrative example, we’ll continue to use the fictitious company we used in the example in the previous section and assume the company has decided to export to a new market. We’ll assume that there is spare productive capacity and that therefore no investment in additional productive capacity is needed. The recipe of the product for this new market is the same as for the domestic market, so direct production costs also stay the same. An investment of $500,000 is required in order to adapt packaging for the new market, and we’ll also assume that we need to spend $200,000 in marketing. Moreover, the company needs to employ an additional sales representative for this market whose salary is $50,000 per year, and we’ll need to pay warehouse rental costs of $60,000 per year. The estimated quantity for this market is 200 tonnes per year. Targeted price is to be 5% cheaper than the competitor with the lowest price on that market (this competitor sells at $48 per kilo). Our company is already profitable in the domestic market. Transportation costs to this market are $6.00 per kilo to the rented warehouse and on average $2.00 per kilo from the rented warehouse to retail stores. Customers in this new market pay on average in 60 days, and stocks in the warehouse will always be kept at 30 tonnes.

Pricing Strategy No. 3: As a Negotiating Tool/Target

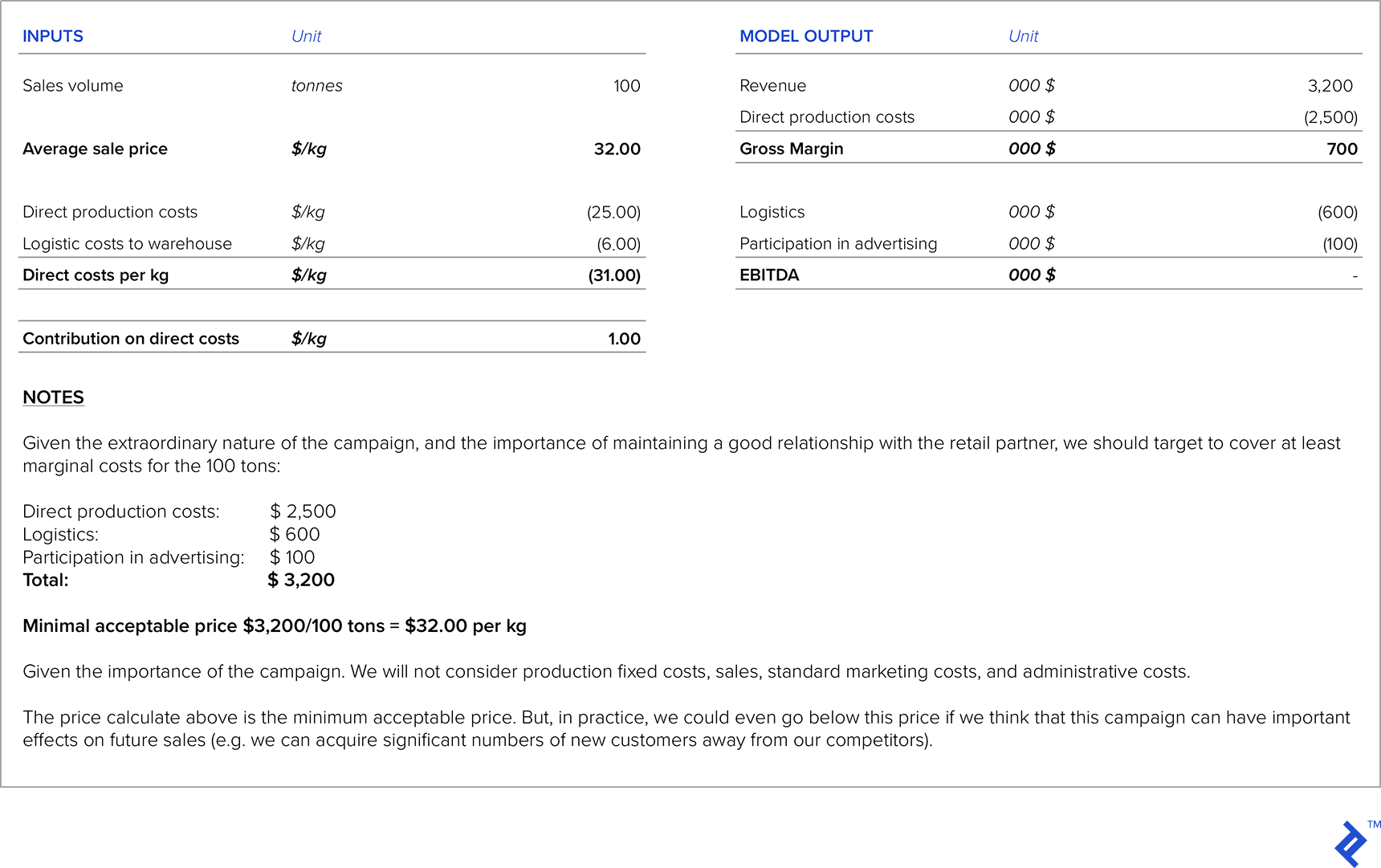

When large retail chains are your partners, they will frequently approach you with requests for price reductions. In these situations, it is very important that you at least cover direct costs of production and logistics. Sometimes, you will even be willing to sacrifice part of the margin, because this may help foster a good relationship with the retail chain. There are also situations where retail chains will help boost your product with better positioning in their stores or co-branding campaigns, but in return, you have to participate in the marketing expenses or pay them additional service fees. In these situations, it is very important to carefully calculate the impact of those expenses on your targeted margin and profitability.

Let’s assume that the company from our first example is contacted by their retail chain partner. They want to organize a special promotion of this product for their upcoming Christmas sale and want to include a discount of up to 50%. They ask you for the lowest possible price you are ready to offer for 100 tonnes of the product. Moreover, to be included in the upcoming promotion, you are expected to participate in the advertising costs for a total of $100,000.

Pricing Strategy No. 4: New Product Launch

When a new product is launched, it is very important to benchmark to similar products on the market or to a substitute for this new product. There are two possible pricing strategies for the new product:

- We set a high initial price, as we believe the new product generates significant value added compared to other similar products or substitutes. This strategy is called price skimming.

- We set a low initial price in order to motivate customers to buy it, and in order to take market share away from similar products or substitutes. This strategy is called price penetration.

On the cost side, it is very important to take into account all the costs related to the new product. A very important question here are the investments required, which can be high due to the need for new equipment (or adjustments to existing equipment), market research, etc. So the margin which will be generated by the new product should be calculated against all additional investments in order to calculate relevant investment parameters (IRR, NPV, and payback period). Another challenge is to estimate sales quantities for a product which still doesn’t even exist on the market.

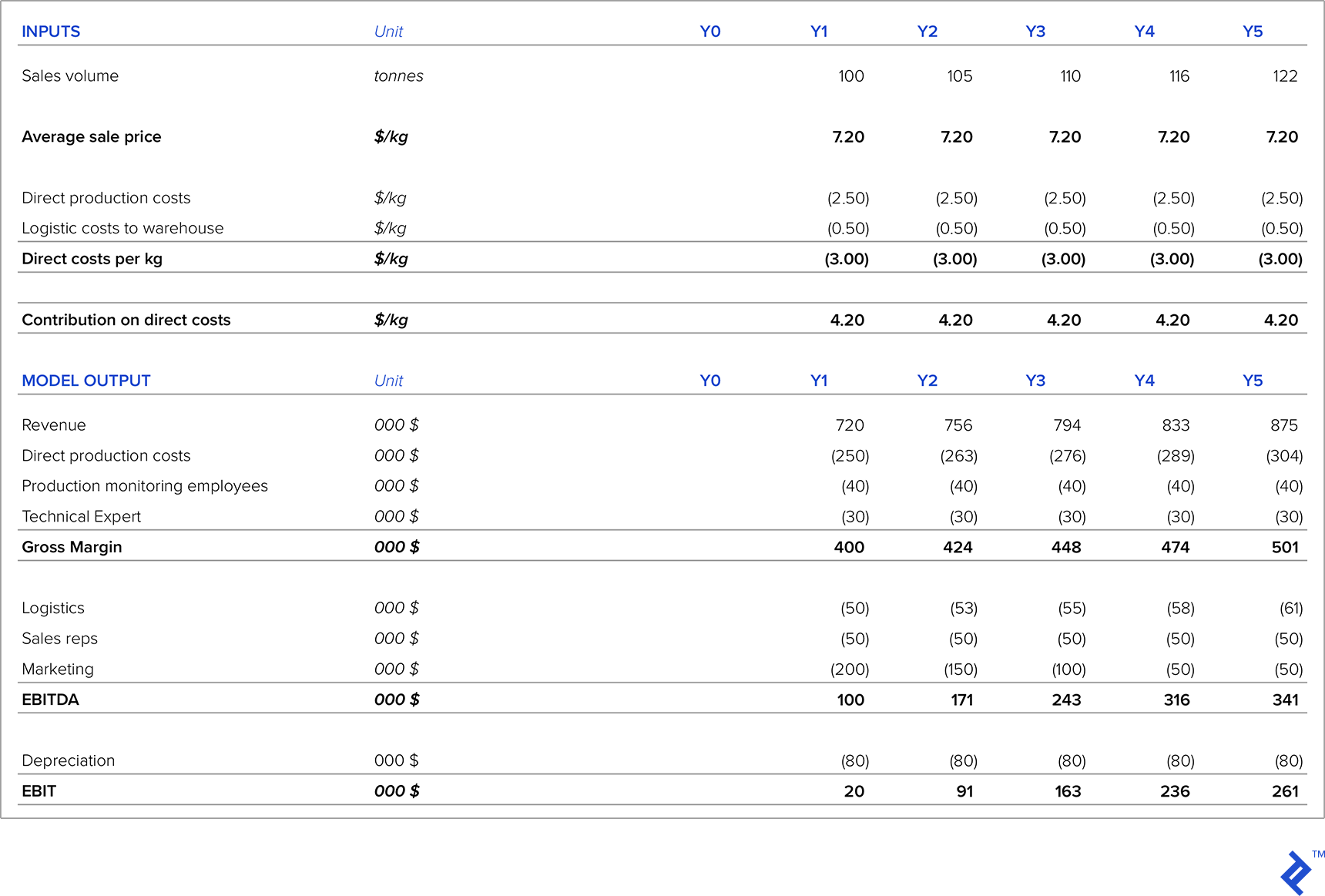

Let’s look at an example for a company that develops fish salami, a new and innovative substitute for existing salami products. The total size of the salami market is 5,000 tonnes. Market research shows that in the first year, with proper marketing campaigns, we will be able to take 2% of the salami market. The average price of other types of salami is $6.00/kg. We estimate that customers will be ready to pay 20% over and above current market prices since this is a new and unique product. The salami market grows, on average, 5% annually, so we will use this as the assumption for our 5-year sales projections.

Direct production costs are $2.50/kilo and logistics costs $0.50/kilo. In our production department, we need to employ a technical expert with an annual salary of $30,000 and two employees for production monitoring each costing $20,000 per year. We also need two new sales reps, each costing $25,000 per year. Marketing expenses are $200,000 in the first year, $150,000 in the second year, $100,000 in the third year, and after that, plateau at $50,000 per year. New equipment is required, costing $400,000 (with linear depreciation over five years). Customers pay on average in 60 days and the minimum required level of inventories is 20 tonnes.

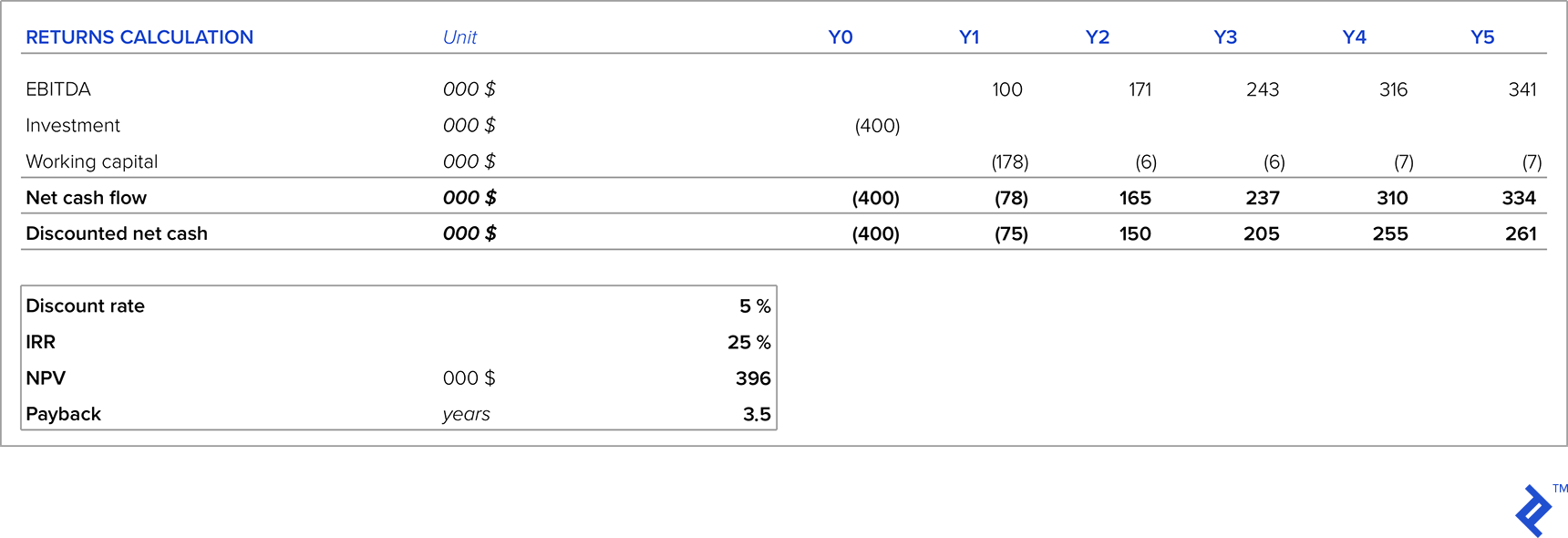

With our P&L projection, we see that during the first five years, the business will be profitable and profit will increase every year as a result of increasing sales and decreasing marketing costs. But, to start with, the new product requires investment in equipment and working capital, so we have taken initial investments into consideration.

Taking into account assumptions on price and quantities, in five years, our investment will generate IRR of 25% (significantly above the discount rate), positive NPV, and a payback period of 3.5 years. If this is within our targeted (or investors’) WACC level, then this is an interesting investment to make. But two key assumptions that were made for the above analysis concerned pricing and sales volumes, particularly since this is a new product with no historical sales track record to base our assumptions off of. Let’s look at which price level brings NPV down to zero—the analysis shows that NPV drops to zero at a price of $6.34, or otherwise put, 12% below our assumed price target. Given this, proper price management is key to the success of this project.

Pricing Strategy No. 5: When Capacity Utilization Is Very Low

When capacity utilization is low (e.g., less than 50%), we face a very high share of depreciation costs relative to product costs. Depreciation costs can be reduced in the P&L in two ways:

- Via divestments, i.e., the sale of assets with low utilization. The biggest question in this scenario is what price we’d be able to fetch for these divestments, especially if there is a situation of general overcapacity at the macro market level.

- By changing internal accounting policies and introducing lower depreciation rates for the assets with low usage. However, this sort of tactic only serves to blur the real picture, so I will neglect it.

From a pricing strategy standpoint, what is usually done in these situations is that depreciation costs are not included in the product costs calculation. The markup is therefore calculated on the costs excluding depreciation. Depreciation is a non-cash expense—it is the result of past investments which we do not have any control over. Therefore, excluding depreciation costs from the pricing calculations shouldn’t have any cash impact.

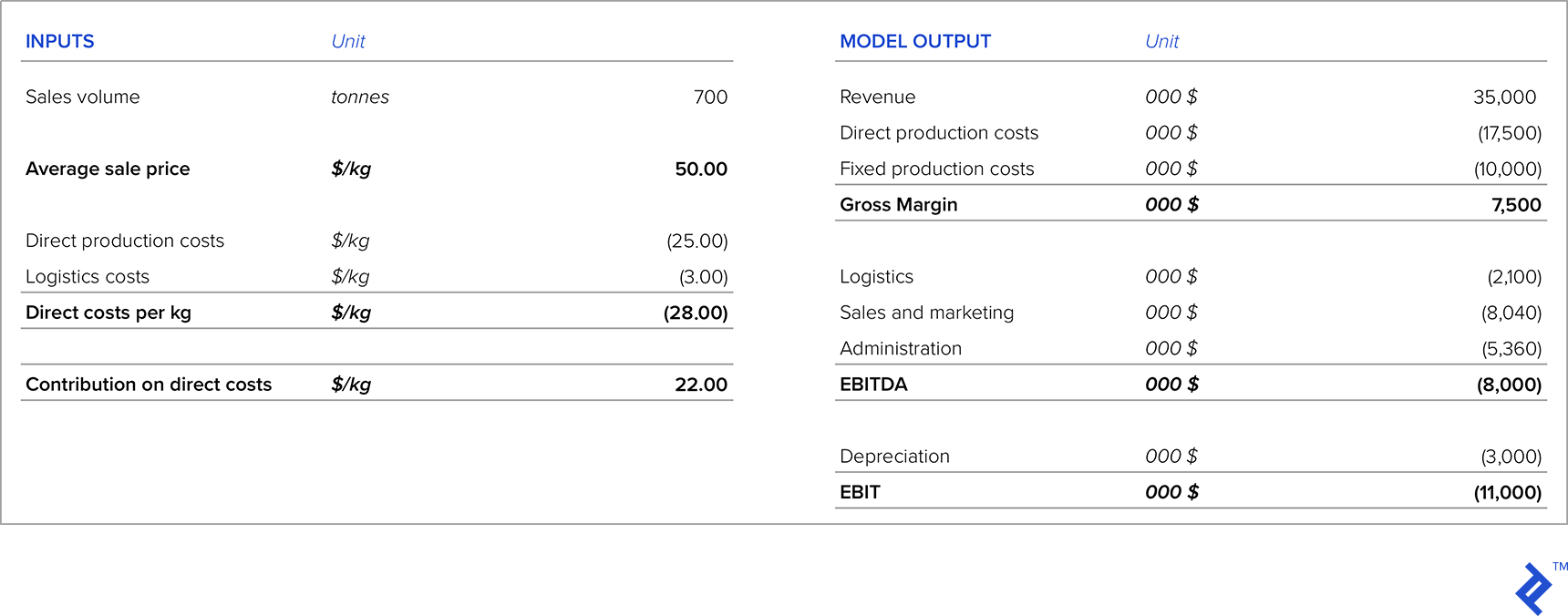

The important part of the pricing analysis here is to compare the margins in the scenario in which we set price by excluding depreciation costs versus the cash generated by the divestment of these assets (assuming we have enough information to know how much we could sell the assets for). Let’s consider an example for a company that sells 700 tonnes of a product at $50/kg, which however has installed capacity of 1,500 tonnes. The income statement currently looks as follows:

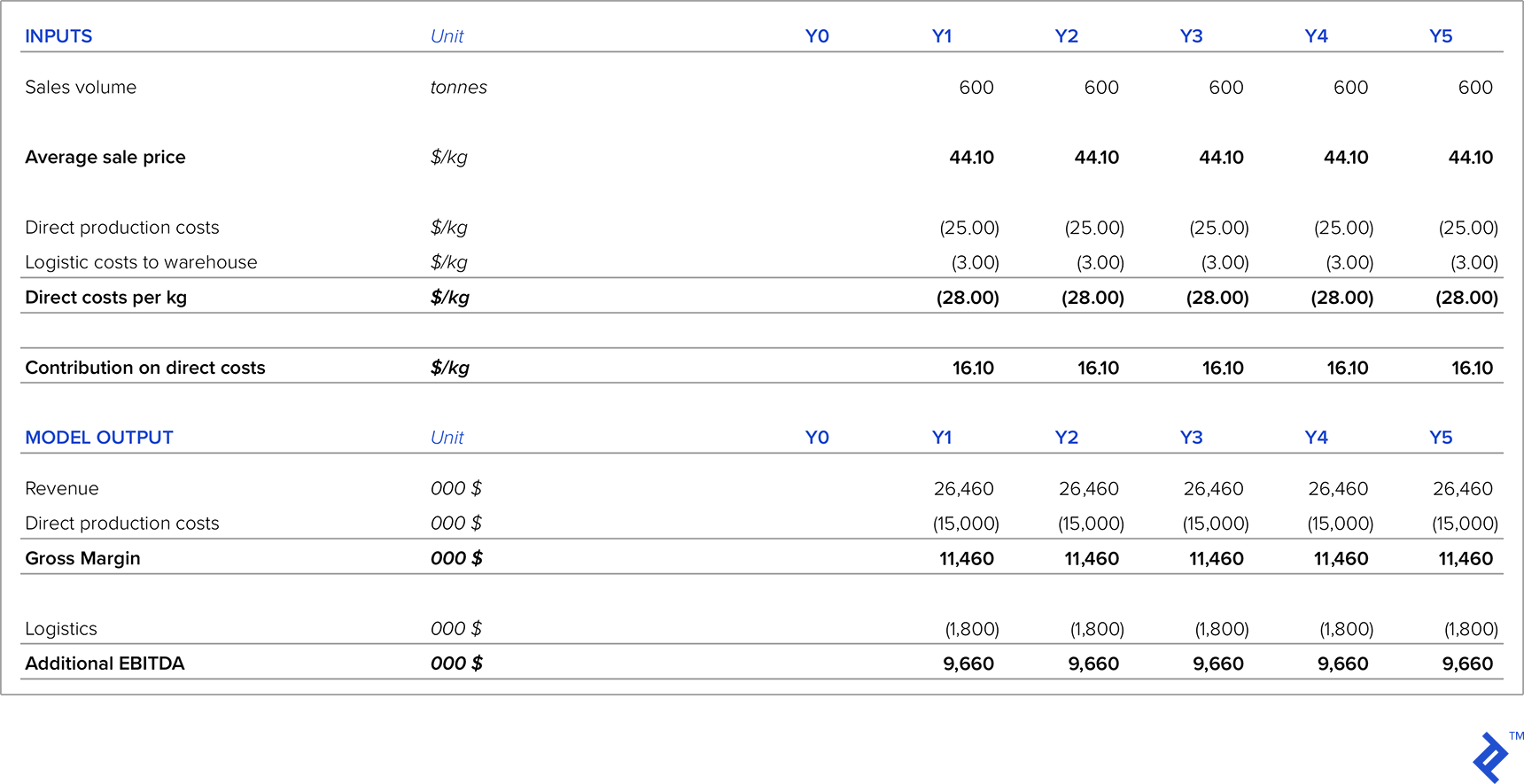

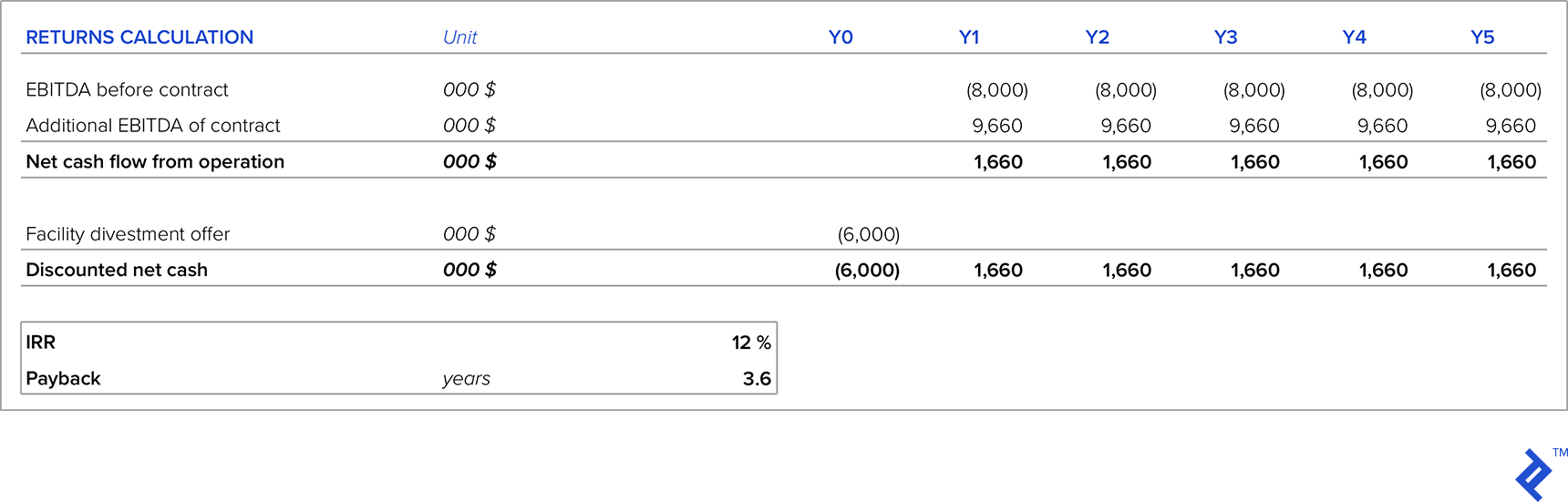

Let’s compare two alternative scenarios. In the first scenario, there is a customer who is ready to sign a five-year contract for 600 tonnes per year. In the second scenario, the company has an offer to sell the full facility for this product for $6 million and the buyerwould take on the dismantling costs. The company has a WACC of 12%, so this is the minimum IRR required for investment or divestment projects. Another criterion is that the maximum payback period can be four years. In both scenarios, the product price is $44.10 per kilo.

Under the first scenario, the additional EBITDA which this contract would generate is:

Let’s now compare this option with the option to divest the facility. The offered price for the facility will be used as an opportunity cost for staying in business.

Pricing Strategy No. 6: Private-label Products

If we work with big retail chains, they sometimes request to produce private label products for them. Even though these products usually generate very low margin, it can have the following positive impacts:

- In situations when we have some spare capacity, it will help generate additional cash

- It can help to establish good relations with the retail chain so that they can boost sales of the private label product

- It is usually based on annualized contracts, so it is secured revenue

- You don’t have associated marketing expenses since the retail chain assumes the responsibility of marketing the product(s)

- You do not have to employ additional sales staff

- The retail chain usually doesn’t request additional rebates and the price is based on annual or longer-term contracts

In these cases, my suggestion would be to cover marginal production costs and add a markup to this, which contributes to fixed costs coverage and to EBITDA.

Pricing Strategy No. 7: Internal Pricing Between Company Profit Centers

Let’s now consider a slightly separate issue related to pricing which often arises within larger companies that are vertically integrated. In particular, this situation can arise when a product from a more “upstream” production stage is then used as an input further downstream.

To illustrate the situation, I’ll use a real example from a company I worked at which was fully integrated and whose activities were as follows:

- Agricultural production with a variety of crops (corn, wheat, barley, etc.)

- Animal food production, where crop plants from the previous stage were used

- Fattened pig farms, which uses animal food from the previous stage

- Fresh meat and final meat products (pâtés, sausages, bacon, ham, ready meals) where the meat from the fattened pigs was used

Because of the interrelated nature of the production stages, pricing issues would sometimes arise. For example, zooming in on the third stage where pigs were fattened, the company faced a choice of either selling them on the market or using them in the next stage as raw material. Considering the first alternative, since the price of fattened pigs has market volatility, when the market price is high it makes more sense to sell fattened pigs on the market rather than to use them as raw material. In these situations, the company can find purchase other raw material in the market which is cheaper than using their own fattened pigs.

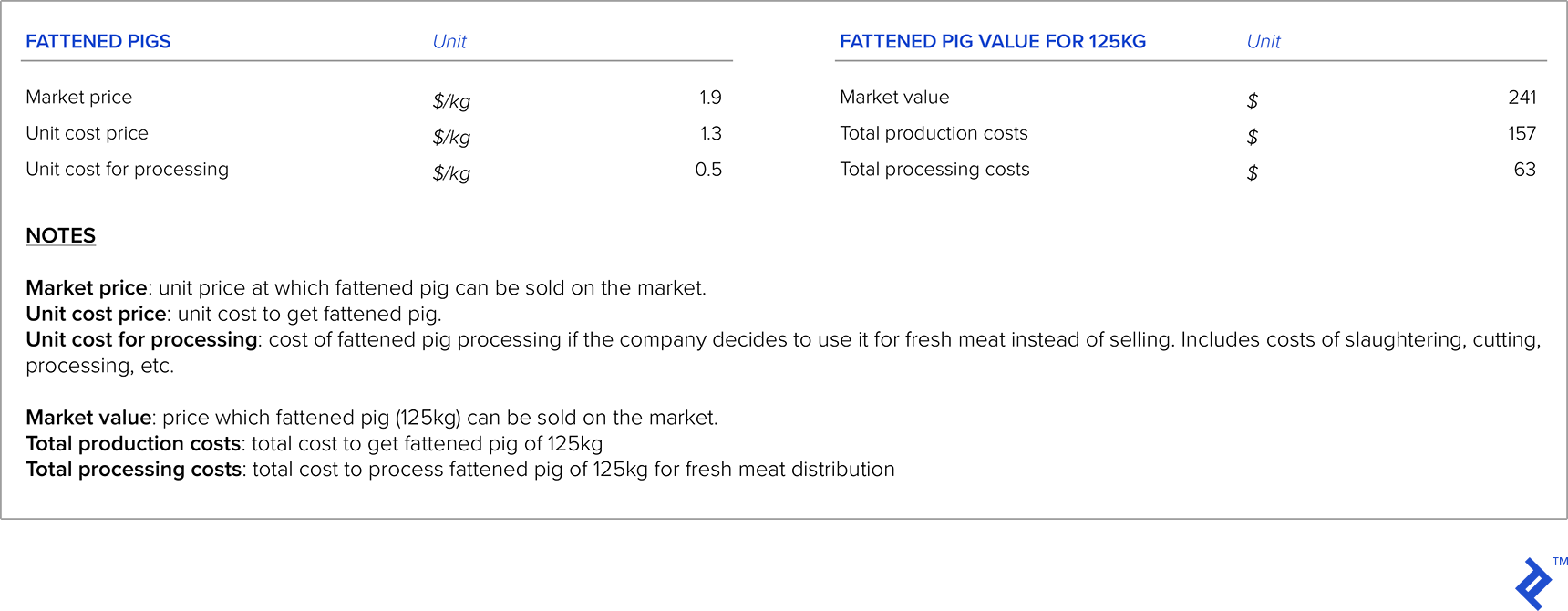

With the above in mind, how should you go about setting the price? Let’s run through the example, in which I’ll assume that the average weight of a fattened pig is 125kg.

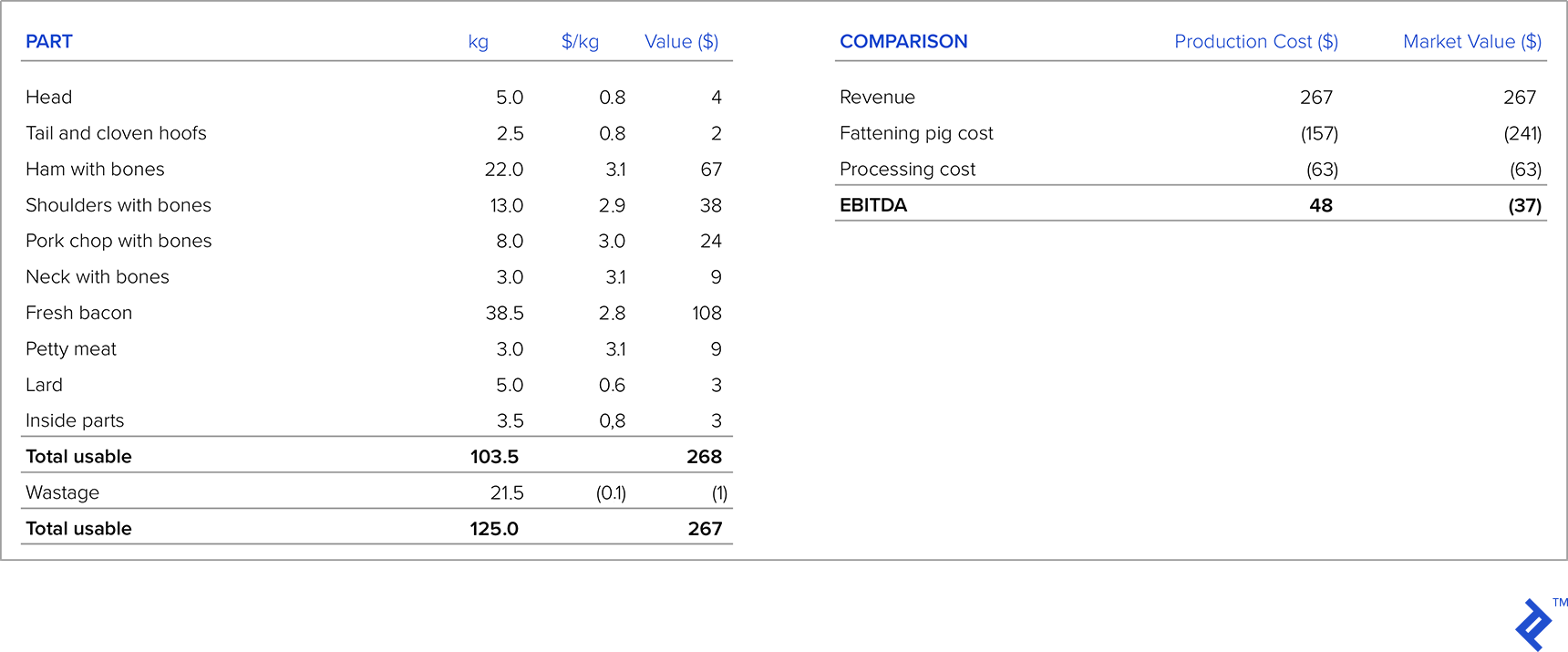

In the table below on the left is the structure of a 125kg fattened pig after cutting, with an offer from a retail chain for each part of the fattened pig and the revenue for each part. Now, let’s compare the profitability of fresh meat distribution by taking production costs and market value of the fattened pig. If we would take into account production cost as an input for the fattened pig cost, we see that company makes a profit per pig of $48. But if we take the value of the fattened pig which the company can get on the market, we see that it makes a loss. So, in situations like these, when there is vertical integration, and there is a market for the product from the previous production stage, we should take market price instead of production cost as the input. In the example above, the company should either sell the fattened pig on the external market or ask the retail chain for a price increase.

Concluding Remarks

Throughout my career, I have witnessed countless examples of situations in which successful or unsuccessful pricing strategies significantly influenced the performance of a company. An example of a successful pricing strategy I faced was in a company which was the first domestic producer of a particular product (previously the product had always been imported). They carefully researched the market size and import competition prices, and executed a very successful introduction of the product, quickly capturing significant market share.

Unfortunately, though, I’ve also witnessed many failed pricing strategies. One example was a manufacturing company I worked for. When we started facing massive import competition, the company didn’t do their homework, assuming customers would continue buying their product even if imports were cheaper. They performed superficial market research, canvassing only their distributors rather than end customers, meaning the results didn’t reflect reality. Soon enough, they started losing market share to lower-cost importers, and the company today is only a shadow of its former self.

There is no single formula for getting pricing strategy right. Many variables have to be taken into account, and many of these are based on assumptions and on subjective or statistical estimations. For this reason, it is inevitable that some pricing strategies fail. In light of this, I always recommend that companies remain flexible. If a pricing strategy is implemented and shows poor results, it should be modified as soon as possible in order to minimize the financial loss and steer the company on a more successful path.

Understanding the basics

What are the four main pricing strategies?

The four main pricing strategies are: premium pricing, price skimming, penetration pricing and economy pricing.

What is the pricing structure?

Pricing structure is a consistent, uniform, planned approach to the pricing of products and services to achieve business and marketing goals.

What are the pricing methods?

Examples of pricing methods include: cost-based pricing, demand-based pricing, competition-based pricing, value pricing, target return pricing, going rate principle, and transfer pricing.

How do you determine pricing strategy?

Pricing strategy refers to the method companies used to price their products or services.

What is skimming and penetration pricing?

Price skimming is a pricing strategy in which a marketer sets a relatively high initial price for a product or service at first, then lowers the price over time. Penetration pricing is a pricing strategy where the price of a product is initially set low to rapidly reach a wide fraction of the market.

Dalibor Pajic

Novi Sad, Vojvodina, Serbia

Member since November 2, 2018

About the author

Dalibor is a CFO with over 15 years of experience in corporate finance, investment management, pricing management, and business development.

PREVIOUSLY AT