Paying It Forward: Understanding Leveraged Buyouts

Fully leveraged buyouts are among the most mythical and highly touted transactions on Wall Street. Yet, their success is predicated on successful comprehension of a business’s potential and the ability to negotiate the right terms for a deal.

Fully leveraged buyouts are among the most mythical and highly touted transactions on Wall Street. Yet, their success is predicated on successful comprehension of a business’s potential and the ability to negotiate the right terms for a deal.

Martin is a seasoned real estate and PE executive who has completed $200+ million in projects and advised a range of Fortune 500 companies.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

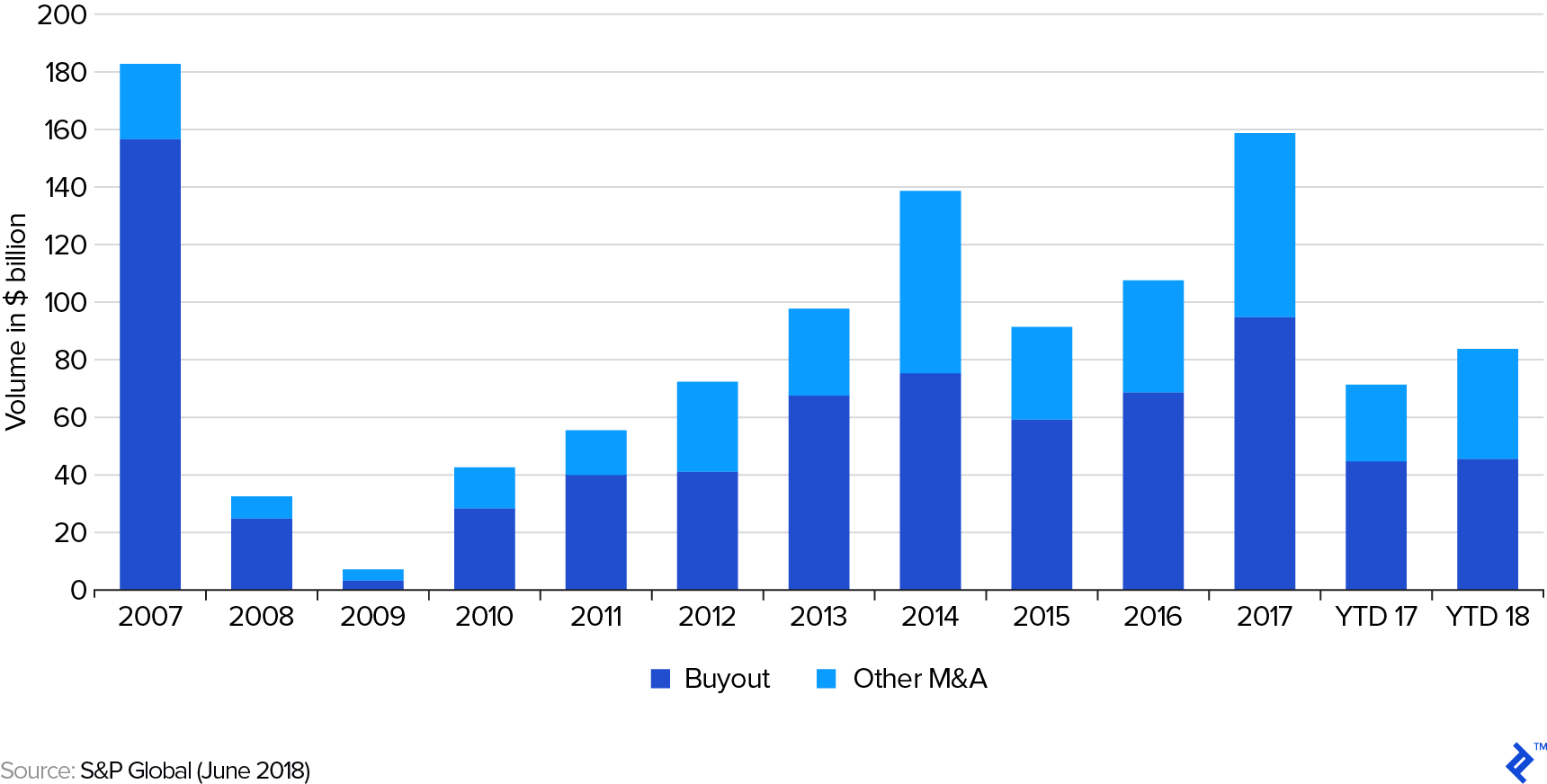

Leveraged buyouts (LBOs) are among the most mythical and highly touted transactions on Wall Street, and hardly a week passes that a new deal isn’t announced, led by some enterprising private equity firm at eye-popping prices and scalding leverage. The market itself is also large and fluid, and recent S&P Global estimates have overall buyout volume in the US in 2017 at approximately $40 billion and growing.

Global Historic Leveraged Buyout Volumes

The deals are exciting, the gains (and the losses) can be enormous, and the transactions involved can seem quite complicated to the untrained eye (and when you get into the details, they usually are). But, at a high level, the concept of an LBO is quite simple.

What Is a Leveraged Buyout?

Matt Levine of Bloomberg defines LBOs quite neatly: “You borrow a lot of money to buy a company, and then you try to operate the company in a way that makes enough money to pay back the debt and make you rich. Sometimes this works and everyone is happy. Sometimes it doesn’t work and at least some people are sad.”

Simple enough?

Wikipedia has a more technical view: “A leveraged buyout is a financial transaction in which a company is purchased with a combination of equity and debt, such that the company’s cash flow is the collateral used to secure and repay the borrowed money. The use of debt, which normally has a lower cost of capital than equity, serves to reduce the overall cost of financing the acquisition. The cost of debt is lower because interest payments often reduce corporate income tax liability, whereas dividend payments normally do not. This reduced cost of financing allows greater gains to accrue to the equity, and, as a result, the debt serves as a lever to increase the returns to the equity.”

This definition may be accurate, but who can survive on such a spare meal?

My personal view is that an LBO is one of the many choices at the nexus of how to use investable cash and how to finance a company. In certain situations, an LBO can be an excellent choice on both counts. In other cases, not so much. In this article, I will outline some of the reasons an LBO might be pursued, why it might be different from other choices that exist to invest in the equity of a company, and the nuts and bolts of modeling a potential deal.

The Five Ways to Make Money as an LBO Investor

Really, there are only five ways to make money as an LBO investor, or really as an investor in general:

- Asset improvement – which we can split into:

- Revenue growth

- Expense reduction

- Financial engineering

- Market timing

- Market beta

That’s it. If you can’t find it in one of those categories, then it’s not there. There are also arguments to be made in favor of or against each of these things (I have serious reservations, for example, that market timing is a viable pathway). But different investors have different opinions and bring different expertise to their investments, and another investor might find that pathway to be a viable strategy.

Leveraged buyouts are interesting in that they can play on all of these elements, with certain transactions relying more on one or the other as the underlying rationale for the investment thesis.

Revenue Growth

Strategies relying on revenue growth involve buying a company and growing its revenue at a similar expense ratio, resulting in an improvement of its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization—or EBITDA—and then refinancing or selling it at the same multiple (but on a higher EBITDA base).

Expense Reduction

These strategies rely on the implementation of cost-cutting programs. Similar to the revenue growth model, the changes made aim to improve EBITDA, ultimately leading to a refinance or sale at the same multiple (but on a higher EBITDA base).

Financial Engineering

In some ways, the defining element of an LBO is the concept of changing a company’s cost of capital by implementing a different financial structure, irrespective of whether the company’s operations (in terms of revenues and expenses) change or not. Three examples of financial engineering strategies are:

- Reduce a company’s weighted average cost of capital by incurring a larger amount of debt (or other more efficient capital) than exists prior to acquisition, resulting in a higher yield to equity.

- Re-figure a company’s assets to lower its capital costs via pseudo-financing transactions. For example, through the sale-leaseback of company real properties or capital assets, sale and licensing of key intellectual property, factoring of other assets the company may control, or the implementation of more aggressive working capital plans.

- Combine a company with other companies or assets that the investor owns, increasing its scale so that the market will be willing to pay a higher multiple for the combined company: Known as a roll-up strategy, this is an often-used strategy in the retail sector—for example, where one can often buy franchises at a lower multiple as single stores and sell them for a higher multiple after a certain critical mass has been achieved in terms of number of stores held by the organization.

Market Timing

A company is bought with the conviction that the equity multiple at which it is priced will improve and create the opportunity for a refinance/sale at better terms than exist in the current market.

While this strategy needs to be mentioned and, ultimately, changes in market price expectations play into all investments of any kind, in my experience, I have yet to find any investor that can reliably predict market price changes over long periods of time. (If that’s you, please reach out—I’d like to invest.)

Market Beta

The market beta strategy is similar to market timing in that the investor implementing the strategy is relying on market forces—rather than changes at the asset level—to drive returns. The difference, though, is that the market beta investor is agnostic about a company’s growth prospects and changes in market pricing, but instead has the mentality that exposure to the market over long periods of time has historically delivered earnings. The market beta investor has the perspective more of an index-fund investor, trying to diversify investments and relying on the long-term growth of assets in general to deliver earnings.

A typical LBO transaction may include a combination of many or even all of these factors in varying degrees, and it’s useful to ask when evaluating a potential investment, “Which of these things am I relying on for my returns?” While it is only anecdotal, in my experience, the first three elements are much more controllable than the latter two, and a plan that involves timing the market or just being in the game seldom results in alpha returns.

Tax Shields and Loan Covenants

While the majority of strategies to succeed in an LBO acquisition are fairly straightforward (at least conceptually, if maybe not practically), there are other aspects that are not quite as up front. One of the most important of these, in my opinion, is the inappropriately named tax shield. While I don’t like the term, I myself will use it in the rest of this article because it is effectively ubiquitous in LBOs. I would strongly prefer the term to be the more descriptively named tax transfer, or tax reallocation, either of which would more clearly underline the true dynamics of this element.

The underlying concept of tax shields is that in the majority of cases, a corporation must pay taxes on its profits (which ultimately belong to the company’s equity holders), but not on interest paid to a lender, which is considered an expense of the business. The term tax shield then is derived from the notion that if a company has more debt, and therefore uses a greater portion of its operating profits to pay for interest, those profits are in part protected from taxation.

Issues with Tax Shields

I have two quibbles with tax shields.

Firstly, having a situation where the company you own has less profit and calling it a shield seems a little disingenuous. And second, while a company may not pay taxes on interest, the lender certainly will. Interest income is taxed, and often at a high rate. So, really, what is going on is that the responsibility for paying taxes on a part of an organization’s profit is being shifted to its lender (a transfer, not a shield). And one may ask how a lender might want to be compensated for such a transfer?

This is a good moment to shift to the lender’s perspective, which is incredibly important in an LBO deal. As you may have noticed, the first word in LBO is leveraged, and that is essentially what the game is all about. While lenders come in all shapes and sizes, the lending market as a whole does the job of pricing credit risk, with low-risk loans often having a cost at only a small spread to the market’s risk free rate, and high-risk loans having a much higher rate, potentially even including an equity participation component or convertibility feature which would allow the debt to have equity-like returns.

Paired with the risk-based pricing are risk-based terms. What I mean by that is that if a lender is providing a low-risk loan, they are likely to have few controls, no guarantees, limited reporting, and a great deal of flexibility for the borrower. The same lender providing a higher-risk loan may require all kinds of guarantees, covenants, and reporting. This makes sense, as the higher-risk lender will want additional assurances and incentive alignment from a company’s owners and affiliates and will want to limit the types of actions the company can take as well as recieve prompt information about the company’s financial health.

These elements, put together, can have broad implications for the viability of an LBO, and so the devil is in the details. A loan that doubles a company’s debt obligations but also dramatically increases the interest rate it pays on those obligations may not be accretive to the company at all, tax shield be damned. And a loan that has strict operating covenants restricting investments in growth or future acquisitions won’t work if the business plan of the LBO transaction is to drive revenue growth at the company through add-on purchases or heavy investments in organic growth. The business plan and debt plan have to work together, and a lot of the success of an LBO transaction is predicated on knowing what the debt market will bear and what it will accept relative to a specific opportunity with respect to pricing and terms.

How to Analyze an LBO Transaction

Shifting gears from the general concepts underlying LBOs, let’s discuss LBO value drivers through an analysis of a potential transaction from a financial perspective.

The analysis of an LBO is fairly straightforward once you have an established set of assumptions for a company’s current and future operations, its value relative to those operations and the cost of debt—and other capital in the marketplace—for the transaction.

The goal of LBO analysis then is to derive the likely value of the company’s equity in a period of years past its acquisition and to combine that value estimate with any other cash that can be distributed by the company along the way (which in many cases is limited, as current cash in an LBO is often either reinvested in the company to drive growth or used to repay debt). Once those numbers are calculated, then it’s fairly simple to come up with the projected total rate of return using our favorite return metrics: usually IRR, equity multiple, or net profit.

Drilling down into an additional level of detail and focusing specifically on the future value of a company’s equity, the approach that usually makes the most sense is to estimate the company’s future income (most often presented as some version of EBITDA) and its value multiple, usually presented as the company’s enterprise value/EBITDA and then to layer in debt capital costs and repayments at that future time to calculate the future value of its equity. I use the term “usually” here because other approaches—such as discounted cash flow and other more exotic approaches—do exist, and in addition different multiples and value drivers are sometimes used. But, for LBOs, EV/EBITDA less debt is the approach that I think most reasonably reflects potential acquisitions and is the most market-oriented approach.

The Role of EBITDA

Given its prevalence, let’s discuss EBITDA in a bit more detail. EBITDA is intended to be a reasonable proxy for the amount of pre-tax value the company, as a whole, produces in a given period of time.

Let’s take each element independently to better understand the metric. The metric starts with earnings, which are the company’s accounting earnings based on its ongoing operations. First, interest costs are added back to earnings because interest is an element of the company’s total capitalization, and not a “true” expense of its operations. The way to think about this is that the company produces an overall profit which can be shared by all parties that have a claim on those profits, including both its lenders and its equity investors. By choosing different combinations of debt and equity, you can shift how those earnings are paid to different stakeholders, but the overall amount of profit will not change, so interest expense is really a choice that is made independent of the company’s operational success. It’s part of the capital decision. Not operations.

Next, taxes are added back as they also can vary depending on capital structure and decisions the company makes about its operations, and even based on who the owners of a company are and what its organizational structure is. In short, looking at earnings pre-tax and before interest allows a more stable assessment of business operations, as distinct from the somewhat involved rationale underlying its capitalization and its tax bill.

The first two adjustments to reach EBITDA are fairly straightforward, but the argument for adjusting for depreciation and amortization is not as simple. Depreciation and amortization are removed because they usually relate to historical capital costs of the company and not to its ongoing operations (or at least not clearly).

For example, imagine a company that buys a retail property to operate a clothing store. The company makes a profit that is the difference between the total sales of clothes, the cost of those clothes, and the operational costs it incurs to make those sales happen (and to cover administrative overhead). Accountants, however, will layer on an additional depreciation cost to arrive at the company’s earnings, arguing that each year the business is in operation it “wears out” part of its building. But this expense is an accounting fiction, and potentially totally divorced from reality. What if the store happens to have been opened in Manhattan in the 1980s? The land underneath the store may actually have appreciated substantially during the same time that the business was incurring this “expense,” and may now be worth substantially more than the owner paid for it in the first place. On the other hand, one can also imagine the store having a cash register that may also be depreciated. Here, the depreciation is more accurate, as within a period of years, the cash register may need to be replaced and the value of the existing register at that point may truly be zero. So it really should be considered an expense.

Adjusted EBITDA

These types of arguments often lead one down the path towards an adjusted EBITDA, which is reasonable, but always arguable. All types of costs and elements can be added or removed with respect to any company to arrive at its “true” EBITDA. Let’s leave the depreciation related to the cash register but ignore the depreciation related to the building. But what about the new store we’re opening down the street—should expenses related to that be included in EBITDA? It’s not really related to the existing operation, and they are “one-time” expenses. And what about the windfall made last year buying and selling a unique, vintage item at the store? Should that be included in EBITDA? What about the owner’s son, who is employed at the store but is being paid twice the market rate in salary? Should there be an adjustment for that? Isn’t that really sort of a de facto ownership interest? The slope is slippery and long, but ultimately, the guiding light is to try to arrive at a number that most fairly reflects the stabilized profitability of the business in the long term.

A great example of a debate related to adjusted EBITDA came in 2018 from WeWork. The coworking business used its own proprietary version of the metric in its disclosures for a bond issue, where it creatively found even more add-ons to build up its figures: “It subtracted not only interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, but also basic expenses like marketing, general and administrative, and development and design costs.” An investor looking to invest in the bond issue would have had to consider the company’s argument, and decide if the adjustments were appropriate or not, or to make their own calculation of the company’s long-term profit potential.

Enterprise Value

Enterprise value (EV) is the other important part of the value calculation and reflects the value of the company including its debt, equity, and other ownership claims on the company, less any cash held by the company. The concept is that if EBITDA—or some adjusted version of it—is the stabilized profitability of the company and EV is its total value, and that there is some relationship that can be established between them (EV/EBITDA). That multiple can then be a guide to the future value of the company or can be used as a benchmark for the value of other, similar companies.

Now, if as an investor we know the following variables:

- The equity funding required to complete the transaction

- How much cash we expect to take out of it during the hold period in terms of dividends or buybacks, or via other means

- What the asset is expected to be worth at the end of our investment timeframe, by taking our future projection of EBITDA and multiplying it by our best estimate of future EV/EBITDA

- The amount of debt that will be owed at the time of the exit

- All of our own expenses, in terms of transaction and other holding costs.

Then we will be able to calculate our net cash flow. And from there, we can apply our favorite return target (total profit, cash multiple, IRR, NPV, or whatever we like) and decide if the transaction makes sense. Or at least whether it makes sense to us.

Leverage Multiples: How Much Can Be Borrowed?

Returning to EBITDA for a moment, the other major value to EBITDA-based analysis is that most lenders operating in the LBO space also look at EBITDA as one of the key elements related to the amount they are willing to lend against a business. Consequently, loans and their covenants are often quoted based on EBITDA.

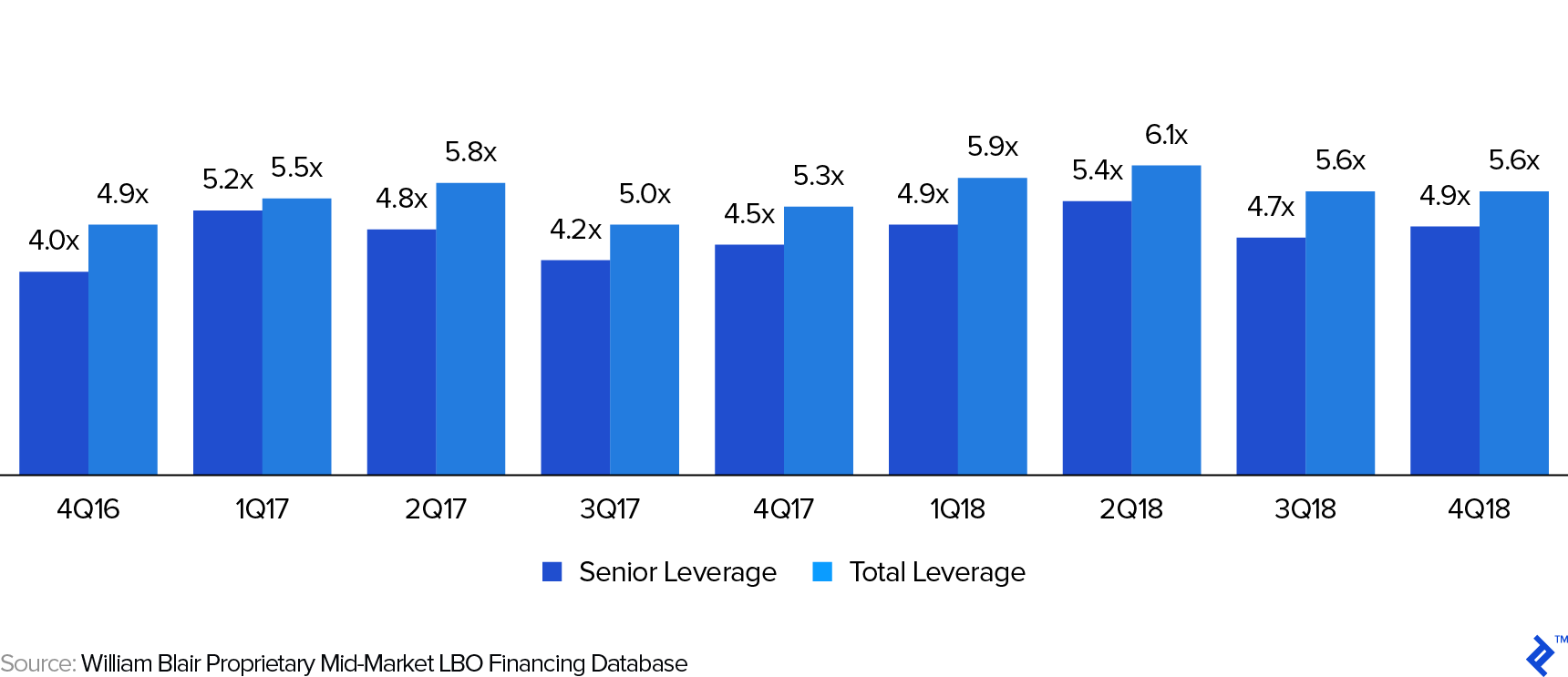

William Blair, an investment bank, for example, reported mid-market EBITDA multiples for loans in the LBO sector for the fourth quarter of 2018 at 5.6x on total leverage.

Global Historic LBO Leverage Multiples

These ratios also give us an indication of the sentiment prevailing in the market at a given time, where higher multiples suggest more optimistic prevailing debt market conditions.

So, knowing a target company’s EBITDA can provide quick guidance on what a reasonable acquisition price might be, how much could be borrowed against the company as collateral, and even what the value of improvements in the company’s operations (in terms of EBITDA) might create in terms of profit above the total acquisition value. EBITDA is really quite a useful measure, if used appropriately.

Putting It All Together

As with nearly all investments, the financials and metrics used to evaluate a deal are just an underpinning to the ideas and concepts involved in the operation and success of a business. It’s best to think of them as a language, which once you understand, you can use to communicate with other professionals to quickly understand or describe a situation, and the plan for a specific acquisition or company.

But, like any language, you can say sensible things or ridiculous things, and at least grammatically there is nothing wrong with either. Personally, I would much rather invest with someone that understands the business and its drivers but is a little fuzzy about the language, metrics, and financials rather than vice versa. Although preferably, an investor can develop both sets of skills and both understand what they are doing and explain it technically.

The other thing that is important to consider when it comes to LBOs, or really any financial transaction on this scale, is that having the concept, understanding it, and generating an analysis supporting it are different from negotiating it, completing diligence, and closing the deal. A canny investor/operator needs to be able to think on their feet as the deal shifts and moves over time as well as when due diligence reveals elements that were not known earlier in the process.

Having a good leveraged buyout model, and a strong feel for the financials can be incredibly useful to this as it allows an investor to think clearly about what a given change implies and quickly come to a conclusion about its materiality and how an issue may be solved—or, on the upside, what the discovery of some unknown value can imply and be used to improve a deal.

I hope this article, while somewhat general, has given you a sense of LBO drivers, as well as some of the issues, challenges, and concepts around completing LBO transactions.

Understanding the basics

What is leveraged buyout modeling?

A leveraged buyout model analyzes the effect of debt servicing on a target company’s ongoing business operations. Interest requirements result in an increased use of free cash flow; thus, the model must project future activities of the business and its ability to grow value and meet its financial obligations.

How does a private equity leveraged buyout work?

Private equity firms may choose a leveraged buyout to acquire a more established company with a viable product line and healthy cash flows. This allows the firm to use the company’s assets as collateral for the loan to acquire it.

Martin Kemeny

San Francisco, CA, United States

Member since February 10, 2017

About the author

Martin is a seasoned real estate and PE executive who has completed $200+ million in projects and advised a range of Fortune 500 companies.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT