Rails Service Objects: A Comprehensive Guide

Rails ships with everything you need to prototype your application quickly, but when your codebase starts growing, you’ll run into scenarios where the conventional Fat Model, Skinny Controller mantra breaks. When your business logic can’t fit in either a model or a controller, that’s when service objects come in and let us separate every business action into its own Ruby object.

Rails ships with everything you need to prototype your application quickly, but when your codebase starts growing, you’ll run into scenarios where the conventional Fat Model, Skinny Controller mantra breaks. When your business logic can’t fit in either a model or a controller, that’s when service objects come in and let us separate every business action into its own Ruby object.

Amin is a developer and entrepreneur who loves writing clean, test-driven Ruby and ES6 code—crafted for CI/CD.

Expertise

Ruby on Rails ships with everything you need to prototype your application quickly, but when your codebase starts growing, you’ll run into scenarios where the conventional Fat Model, Skinny Controller mantra breaks. When your business logic can’t fit into either a model or a controller, that’s when service objects come in and let us separate every business action into its own Ruby object.

In this article, I’ll explain when a service object is required; how to go about writing clean service objects and grouping them together for contributor sanity; the strict rules I impose on my service objects to tie them directly to my business logic; and how not to turn your service objects into a dumping ground for all the code you don’t know what to do with.

Why Do I Need Service Objects?

Try this: What do you do when your application needs to tweet the text from params[:message]?

If you’ve been using vanilla Rails so far, then you’ve probably done something like this:

class TweetController < ApplicationController

def create

send_tweet(params[:message])

end

private

def send_tweet(tweet)

client = Twitter::REST::Client.new do |config|

config.consumer_key = ENV['TWITTER_CONSUMER_KEY']

config.consumer_secret = ENV['TWITTER_CONSUMER_SECRET']

config.access_token = ENV['TWITTER_ACCESS_TOKEN']

config.access_token_secret = ENV['TWITTER_ACCESS_SECRET']

end

client.update(tweet)

end

end

The problem here is that you’ve added at least ten lines to your controller, but they don’t really belong there. Also, what if you wanted to use the same functionality in another controller? Do you move this to a concern? Wait, but this code doesn’t really belong in controllers at all. Why can’t the Twitter API just come with a single prepared object for me to call?

The first time I did this, I felt like I’d done something dirty. My, previously, beautifully lean Rails controllers had started getting fat and I didn’t know what to do. Eventually, I fixed my controller with a service object.

Before you start reading this article, let’s pretend:

- This application handles a Twitter account.

- The Rails Way means “the conventional Ruby on Rails way of doing things” and the book doesn’t exist.

- I’m a Rails expert… which I’m told every day that I am, but I have trouble believing it, so let’s just pretend that I really am one.

What Are Service Objects?

Service objects are Plain Old Ruby Objects (PORO) that are designed to execute one single action in your domain logic and do it well. Consider the example above: Our method already has the logic to do one single thing, and that is to create a tweet. What if this logic was encapsulated within a single Ruby class that we can instantiate and call a method to? Something like:

tweet_creator = TweetCreator.new(params[:message])

tweet_creator.send_tweet

# Later on in the article, we'll add syntactic sugar and shorten the above to:

TweetCreator.call(params[:message])

This is pretty much it; our TweetCreator service object, once created, can be called from anywhere, and it would do this one thing very well.

Creating a Service Object

First let’s create a new TweetCreator in a new folder called app/services:

$ mkdir app/services && touch app/services/tweet_creator.rb

And let’s just dump all our logic inside a new Ruby class:

# app/services/tweet_creator.rb

class TweetCreator

def initialize(message)

@message = message

end

def send_tweet

client = Twitter::REST::Client.new do |config|

config.consumer_key = ENV['TWITTER_CONSUMER_KEY']

config.consumer_secret = ENV['TWITTER_CONSUMER_SECRET']

config.access_token = ENV['TWITTER_ACCESS_TOKEN']

config.access_token_secret = ENV['TWITTER_ACCESS_SECRET']

end

client.update(@message)

end

end

Then you can call TweetCreator.new(params[:message]).send_tweet anywhere in your app, and it will work. Rails will load this object magically because it autoloads everything under app/. Verify this by running:

$ rails c

Running via Spring preloader in process 12417

Loading development environment (Rails 5.1.5)

> puts ActiveSupport::Dependencies.autoload_paths

...

/Users/gilani/Sandbox/nazdeeq/app/services

Want to know more about how autoload works? Read the Autoloading and Reloading Constants Guide.

Adding Syntactic Sugar to Make Rails Service Objects Suck Less

Look, this feels great in theory, but TweetCreator.new(params[:message]).send_tweet is just a mouthful. It’s far too verbose with redundant words… much like HTML (ba-dum tiss!). In all seriousness, though, why do people use HTML when HAML is around? Or even Slim. I guess that’s another article for another time. Back to the task at hand:

TweetCreator is a nice short class name, but the extra cruft around instantiating the object and calling the method is just too long! If only there were precedence in Ruby for calling something and having it execute itself immediately with the given parameters… oh wait, there is! It’s Proc#call.

Proccallinvokes the block, setting the block’s parameters to the values in params using something close to method calling semantics. It returns the value of the last expression evaluated in the block.aproc = Proc.new {|scalar, values| values.map {|value| valuescalar } } aproc.call(9, 1, 2, 3) #=> [9, 18, 27] aproc[9, 1, 2, 3] #=> [9, 18, 27] aproc.(9, 1, 2, 3) #=> [9, 18, 27] aproc.yield(9, 1, 2, 3) #=> [9, 18, 27]

If this confuses you, let me explain. A proc can be call-ed to execute itself with the given parameters. Which means, that if TweetCreator were a proc, we could call it with TweetCreator.call(message) and the result would be equivalent to TweetCreator.new(params[:message]).call, which looks quite similar to our unwieldy old TweetCreator.new(params[:message]).send_tweet.

So let’s make our service object behave more like a proc!

First, because we probably want to reuse this behavior across all our service objects, let’s borrow from the Rails Way and create a class called ApplicationService:

# app/services/application_service.rb

class ApplicationService

def self.call(*args, &block)

new(*args, &block).call

end

end

Did you see what I did there? I added a class method called call that creates a new instance of the class with the arguments or block you pass to it, and calls call on the instance. Exactly what we we wanted! The last thing to do is to rename the method from our TweetCreator class to call, and have the class inherit from ApplicationService:

# app/services/tweet_creator.rb

class TweetCreator < ApplicationService

attr_reader :message

def initialize(message)

@message = message

end

def call

client = Twitter::REST::Client.new do |config|

config.consumer_key = ENV['TWITTER_CONSUMER_KEY']

config.consumer_secret = ENV['TWITTER_CONSUMER_SECRET']

config.access_token = ENV['TWITTER_ACCESS_TOKEN']

config.access_token_secret = ENV['TWITTER_ACCESS_SECRET']

end

client.update(@message)

end

end

And finally, let’s wrap this up by calling our service object in the controller:

class TweetController < ApplicationController

def create

TweetCreator.call(params[:message])

end

end

Grouping Similar Service Objects for Sanity

The example above has only one service object, but in the real world, things can get more complicated. For example, what if you had hundreds of services, and half of them were related business actions, e.g., having a Follower service that followed another Twitter account? Honestly, I’d go insane if a folder contained 200 unique-looking files, so good thing there’s another pattern from the Rails Way that we can copy—I mean, use as inspiration: namespacing.

Let’s pretend we’ve been tasked to create a service object that follows other Twitter profiles.

Let’s look at the name of our previous service object: TweetCreator. It sounds like a person, or at the very least, a role in an organization. Someone that creates Tweets. I like to name my service objects as if they were just that: roles in an organization. Following this convention, I’ll call my new object: ProfileFollower.

Now, since I’m the supreme overlord of this app, I’m going to create a managerial position in my service hierarchy and delegate responsibility for both these services to that position. I’ll call this new managerial position TwitterManager.

Since this manager does nothing but manage, let’s make it a module and nest our service objects under this module. Our folder structure will now look like:

services

├── application_service.rb

└── twitter_manager

├── profile_follower.rb

└── tweet_creator.rb

And our service objects:

# services/twitter_manager/tweet_creator.rb

module TwitterManager

class TweetCreator < ApplicationService

...

end

end

# services/twitter_manager/profile_follower.rb

module TwitterManager

class ProfileFollower < ApplicationService

...

end

end

And our calls will now become TwitterManager::TweetCreator.call(arg), and TwitterManager::ProfileManager.call(arg).

Service Objects to Handle Database Operations

The example above made API calls, but service objects can also be used when all the calls are to your database instead of an API. This is especially helpful if some business actions require multiple database updates wrapped in a transaction. For example, this sample code would use services to record a currency exchange taking place.

module MoneyManager

# exchange currency from one amount to another

class CurrencyExchanger < ApplicationService

...

def call

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

# transfer the original currency to the exchange's account

outgoing_tx = CurrencyTransferrer.call(

from: the_user_account,

to: the_exchange_account,

amount: the_amount,

currency: original_currency

)

# get the exchange rate

rate = ExchangeRateGetter.call(

from: original_currency,

to: new_currency

)

# transfer the new currency back to the user's account

incoming_tx = CurrencyTransferrer.call(

from: the_exchange_account,

to: the_user_account,

amount: the_amount * rate,

currency: new_currency

)

# record the exchange happening

ExchangeRecorder.call(

outgoing_tx: outgoing_tx,

incoming_tx: incoming_tx

)

end

end

end

# record the transfer of money from one account to another in money_accounts

class CurrencyTransferrer < ApplicationService

...

end

# record an exchange event in the money_exchanges table

class ExchangeRecorder < ApplicationService

...

end

# get the exchange rate from an API

class ExchangeRateGetter < ApplicationService

...

end

end

What Do I Return from My Service Object?

We’ve discussed how to call our service object, but what should the object return? There are three ways to approach this:

- Return

trueorfalse - Return a value

- Return an Enum

Return true or false

This one is simple: If an action works as intended, return true; otherwise, return false:

def call

...

return true if client.update(@message)

false

end

Return a Value

If your service object fetches data from somewhere, you probably want to return that value:

def call

...

return false unless exchange_rate

exchange_rate

end

Respond with an Enum

If your service object is a bit more complex, and you want to handle different scenarios, you could just add enums to control the flow of your services:

class ExchangeRecorder < ApplicationService

RETURNS = [

SUCCESS = :success,

FAILURE = :failure,

PARTIAL_SUCCESS = :partial_success

]

def call

foo = do_something

return SUCCESS if foo.success?

return FAILURE if foo.failure?

PARTIAL_SUCCESS

end

private

def do_something

end

end

And then in your app, you can use:

case ExchangeRecorder.call

when ExchangeRecorder::SUCCESS

foo

when ExchangeRecorder::FAILURE

bar

when ExchangeRecorder::PARTIAL_SUCCESS

baz

end

Shouldn’t I Put Service Objects in lib/services Instead of app/services?

This is subjective. People’s opinions differ on where to put their service objects. Some people put them in lib/services, while some create app/services. I fall in the latter camp. Rails’ Getting Started Guide describes the lib/ folder as the place to put “extended modules for your application.”

In my humble opinion, “extended modules” means modules that don’t encapsulate core domain logic and can generally be used across projects. In the wise words of a random Stack Overflow answer, put code in there that “can potentially become its own gem.”

Are Service Objects a Good Idea?

It depends on your use case. Look—the fact that you’re reading this article right now suggests you’re trying to write code that doesn’t exactly belong in a model or controller. I recently read this article about how service objects are an anti-pattern. The author has his opinions, but I respectfully disagree.

Just because some other person overused service objects doesn’t mean they’re inherently bad. At my startup, Nazdeeq, we use service objects as well as non-ActiveRecord models. But the difference between what goes where has always been apparent to me: I keep all business actions in service objects while keeping resources that don’t really need persistence in non-ActiveRecord models. At the end of the day, it’s for you to decide what pattern is good for you.

However, do I think service objects in general are a good idea? Absolutely! They keep my code neatly organized, and what makes me confident in my use of POROs is that Ruby loves objects. No, seriously, Ruby loves objects. It’s insane, totally bonkers, but I love it! Case in point:

> 5.is_a? Object # => true

> 5.class # => Integer

> class Integer

?> def woot

?> 'woot woot'

?> end

?> end # => :woot

> 5.woot # => "woot woot"

See? 5 is literally an object.

In many languages, numbers and other primitive types are not objects. Ruby follows the influence of the Smalltalk language by giving methods and instance variables to all of its types. This eases one’s use of Ruby, since rules applying to objects apply to all of Ruby. Ruby-lang.org

When Should I Not Use a Service Object?

This one’s easy. I have these rules:

-

Does your code handle routing, params or do other controller-y things?

If so, don’t use a service object—your code belongs in the controller. -

Are you trying to share your code in different controllers?

In this case, don’t use a service object—use a concern. -

Is your code like a model that doesn’t need persistence?

If so, don’t use a service object. Use a non-ActiveRecord model instead. -

Is your code a specific business action? (e.g., “Take out the trash,” “Generate a PDF using this text,” or “Calculate the customs duty using these complicated rules”)

In this case, use a service object. That code probably doesn’t logically fit in either your controller or your model.

Of course, these are my rules, so you’re welcome to adapt them to your own use cases. These have worked very well for me, but your mileage may vary.

Rules for Writing Good Service Objects

I have a four rules for creating service objects. These aren’t written in stone, and if you really want to break them, you can, but I will probably ask you to change it in code reviews unless your reasoning is sound.

Rule 1: Only One Public Method per Service Object

Service objects are single business actions. You can change the name of your public method if you like. I prefer using call, but Gitlab CE’s codebase calls it execute and other people may use perform. Use whatever you want—you could call it nermin for all I care. Just don’t create two public methods for a single service object. Break it into two objects if you need to.

Rule 2: Name Service Objects Like Dumb Roles at a Company

Service objects are single business actions. Imagine if you hired one person at the company to do that one job, what would you call them? If their job is to create tweets, call them TweetCreator. If their job is to read specific tweets, call them TweetReader.

Rule 3: Don’t Create Generic Objects to Perform Multiple Actions

Service objects are single business actions. I broke the functionality into two pieces: TweetReader, and ProfileFollower. What I didn’t do is create a single generic object called TwitterHandler and dump all of the API functionality in there. Please don’t do this. This goes against the “business action” mindset and makes the service object look like the Twitter Fairy. If you want to share code among the business objects, just create a BaseTwitterManager object or module and mix that into your service objects.

Rule 4: Handle Exceptions Inside the Service Object

For the umpteenth time: Service objects are single business actions. I can’t say this enough. If you’ve got a person that reads tweets, they’ll either give you the tweet, or say, “This tweet doesn’t exist.” Similarly, don’t let your service object panic, jump on your controller’s desk, and tell it to halt all work because “Error!” Just return false and let the controller move on from there.

Credits and Next Steps

This article wouldn’t have been possible without the amazing community of Ruby developers at Toptal. If I ever run into a problem, the community is the most helpful group of talented engineers I’ve ever met.

If you’re using service objects, you may find yourself wondering how to force certain answers while testing. I recommend reading this article on how to create mock service objects in Rspec that will always return the result you want, without actually hitting the service object!

If you want to learn more about Ruby tricks, I recommend Creating a Ruby DSL: A Guide to Advanced Metaprogramming by fellow Toptaler Máté Solymosi. He breaks down how the routes.rb file doesn’t feel like Ruby and helps you build your own DSL.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

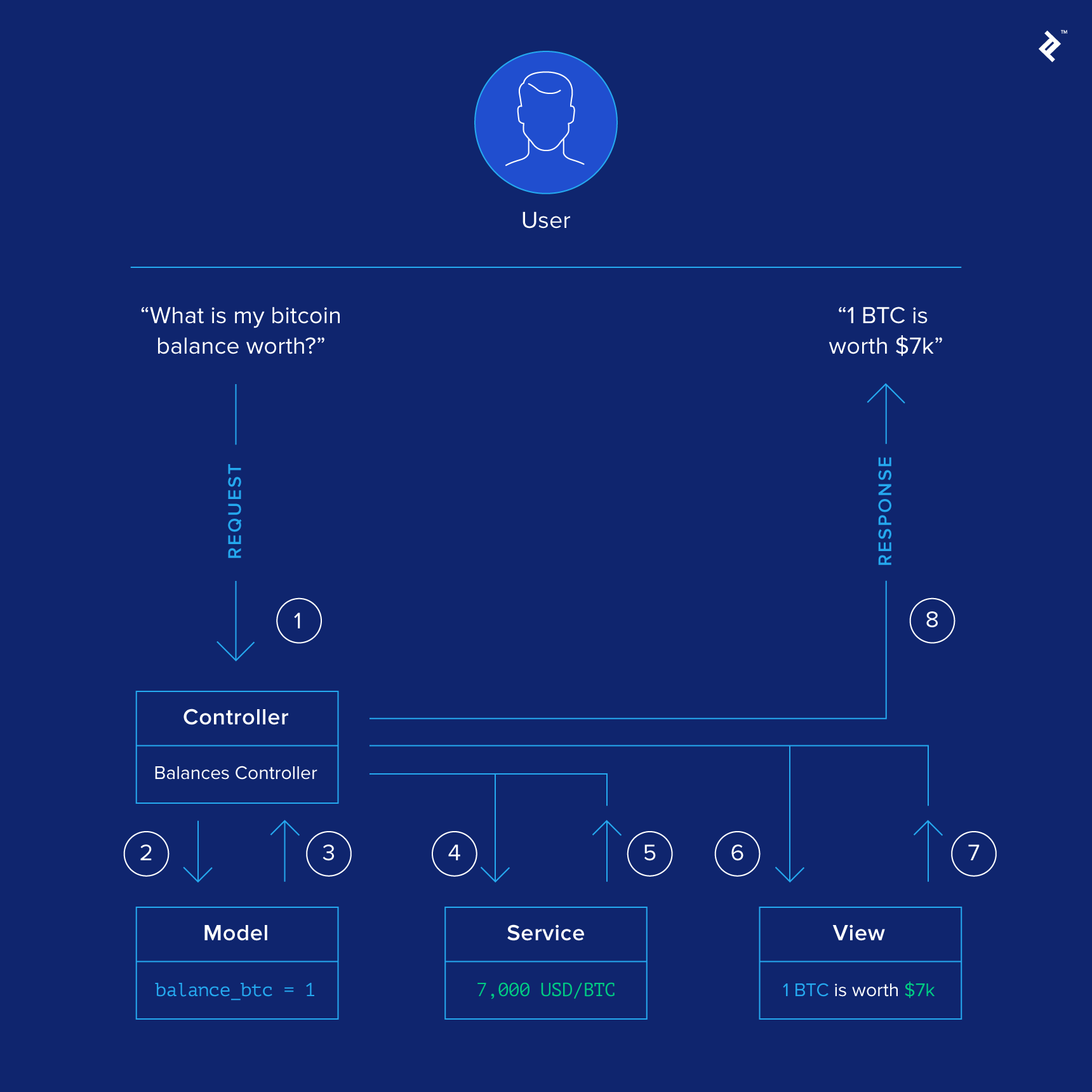

What is a controller in Rails?

A controller in Rails is the layer responsible for understanding, processing, and responding to your request. It uses the model layer to fetch data and the view layer to create the presentation of the response.

What is a service object in Rails?

A service object in Rails is a plain old Ruby object created for a specific business action. It usually contains code that doesn’t fit in the model or view layer, e.g., actions via a third-party API like posting a tweet.

Where do I put my code in Rails when it doesn't fit in a model or controller?

There are many places to put your code, such as Concerns, Config, Mailers, and Jobs. Sometimes, though, what you’re looking for is a service object. Read the article to understand my take on service objects.

What is Fat Model, Skinny Controller?

Fat Model and Skinny Controller is a design pattern that recommends keeping your controllers lean with little code, and doing all the heavy lifting in your model layer.

What are params in Ruby on Rails?

In Rails, params accompany the request, whether as a POST request or Query String. It is available in the Controller as a variable called params. For more details, look up ActionDispatch::Http::Parameters.

Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan

Member since January 27, 2017

About the author

Amin is a developer and entrepreneur who loves writing clean, test-driven Ruby and ES6 code—crafted for CI/CD.