How to Avoid 5 Types of Cognitive Bias in User Research

Cognitive biases can skew user research, leading to design changes that don’t address your customers’ real needs. Build digital products that users will love by mitigating these common biases.

Cognitive biases can skew user research, leading to design changes that don’t address your customers’ real needs. Build digital products that users will love by mitigating these common biases.

Rima is a product designer with expertise in UI/UX design, graphic design, digital marketing, and user research. She has worked across various industries to create user-focused and aesthetically pleasing digital products, and spent six years at the global software development company Volo.

Expertise

Previous Role

UX/UI DesignerPREVIOUSLY AT

Most designers understand the crucial role that user research plays in creating an exceptional user experience. But even when designers prioritize research, different cognitive biases can impact results and jeopardize digital products. Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that affect how people interpret information and make decisions. While all humans are subject to cognitive biases, many people aren’t conscious of their effects. In fact, research suggests the existence of a bias blind spot, in which people tend to believe they are less biased than their peers even if they are not.

With seven years of experience conducting surveys and gathering user feedback, I’ve encountered many ways that cognitive bias can impact results and influence design decisions. By being aware of their own cognitive biases and employing effective strategies to remove bias from their work, designers can conduct research that accurately reflects user needs, informing the solutions that can truly improve a product’s design and better serve the customer. In this article I examine five types of cognitive bias in user research and the steps designers can take to mitigate them and create more successful products.

Confirmation Bias: Selecting Facts That Align With a Predisposed Belief

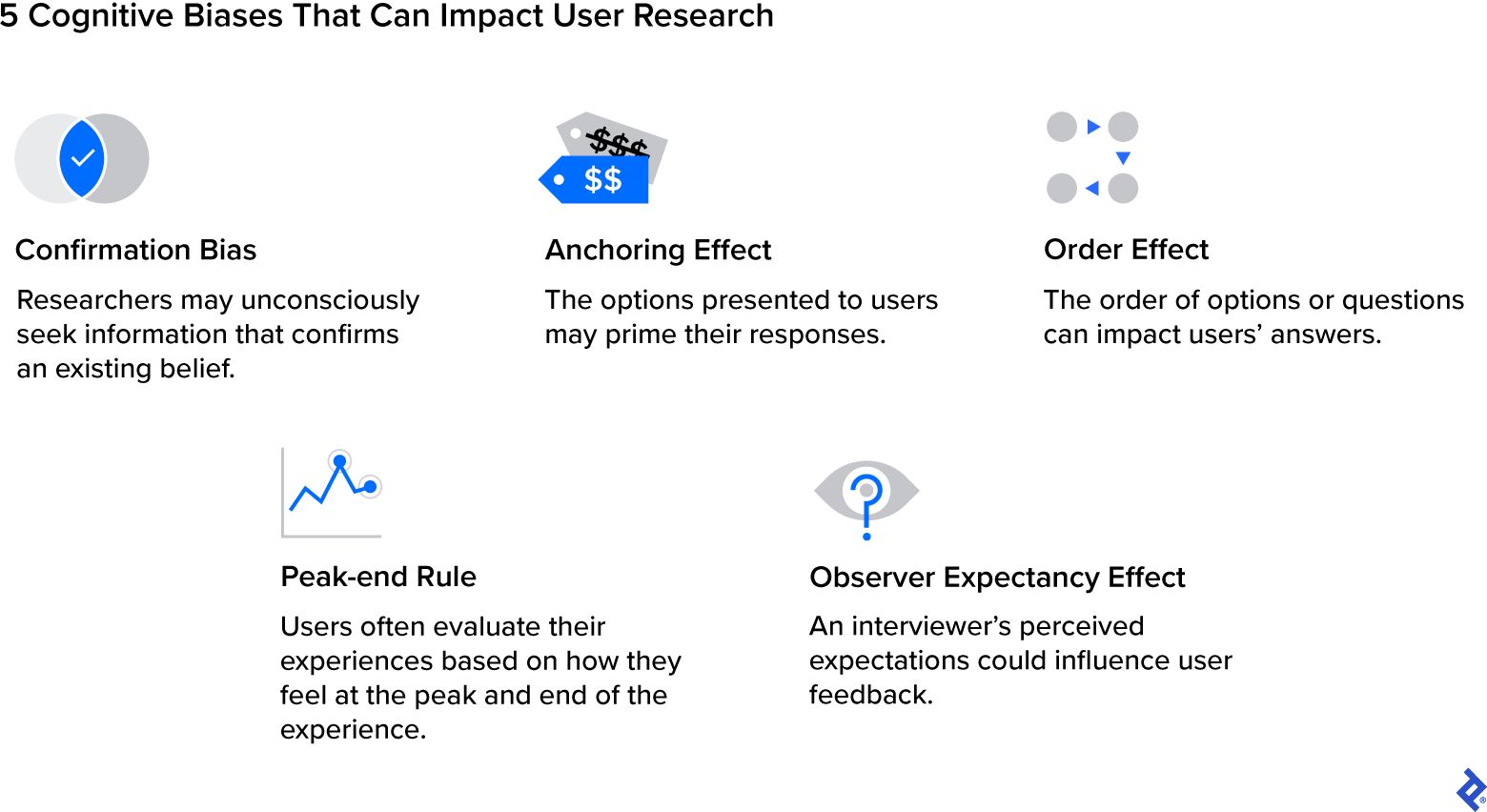

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek information that confirms an existing belief or assumption while ignoring facts that don’t fit this perspective. In user research, confirmation bias may manifest itself as designers prioritizing feedback that affirms their own opinions about a design and disregarding constructive feedback they disagree with. This approach will naturally lead to design solutions that don’t adequately address users’ problems.

I saw this bias in action when a design team I was working with recently collected user feedback about a software development company’s website. Multiple participants expressed a desire for a shorter onboarding process into the website. That surprised me because I thought it was an intuitive approach. Instead of addressing that feedback, I prioritized comments that didn’t focus on onboarding, such as the position of a button or a distracting color design.

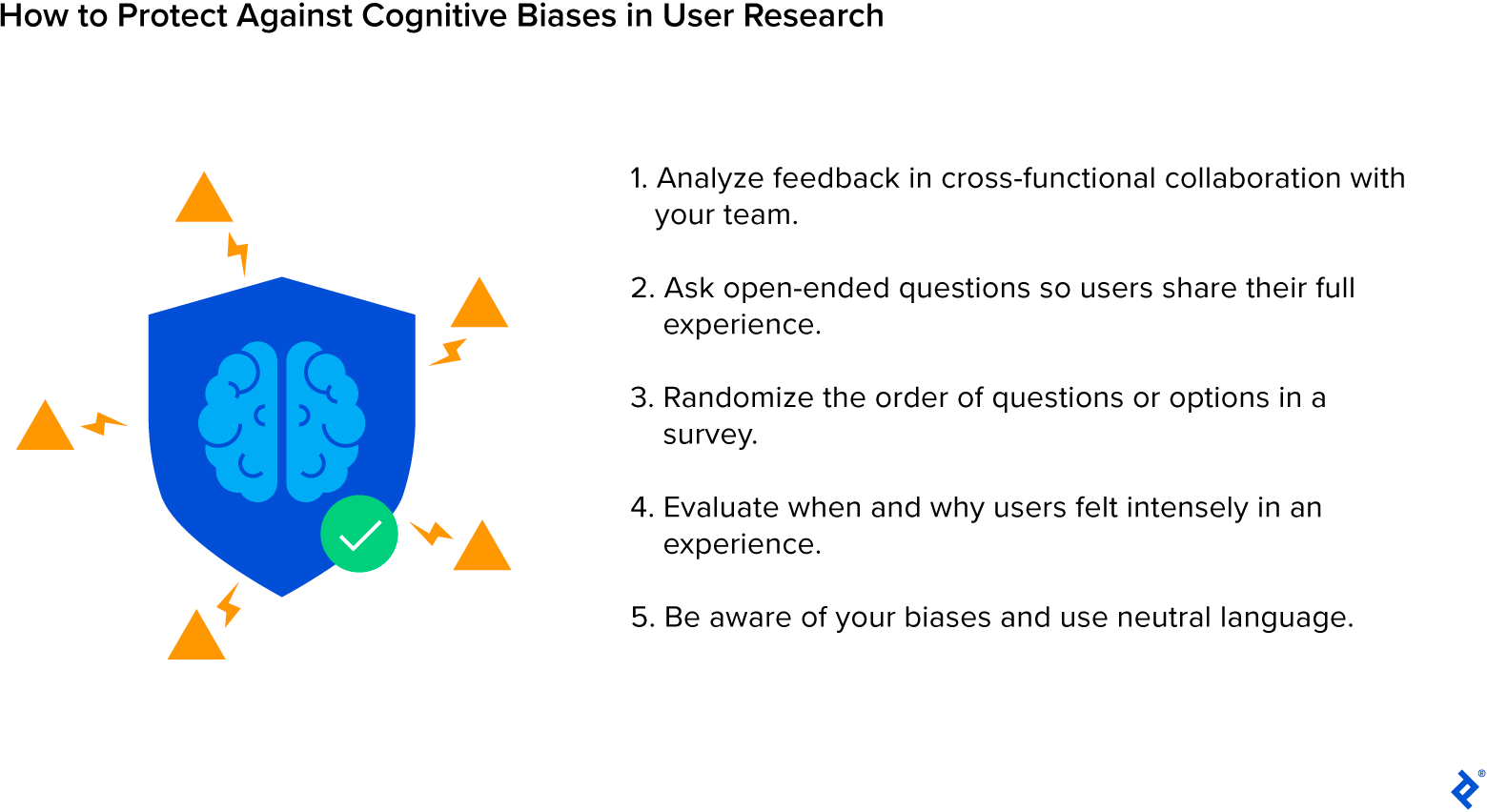

It was only after our team analyzed feedback with an affinity diagram—an organized cluster of notes grouped by a shared theme or concept—that the volume of complaints about the onboarding became obvious, and I recognized my bias for what it was.

To address the issue with onboarding, we reduced the number of questions asked on-screen and moved them to a later step. User tests confirmed that the new process felt shorter and smoother to users. The affinity mapping reduced our risk of unevenly focusing on one aspect of user feedback and encouraged us to visualize all data points.

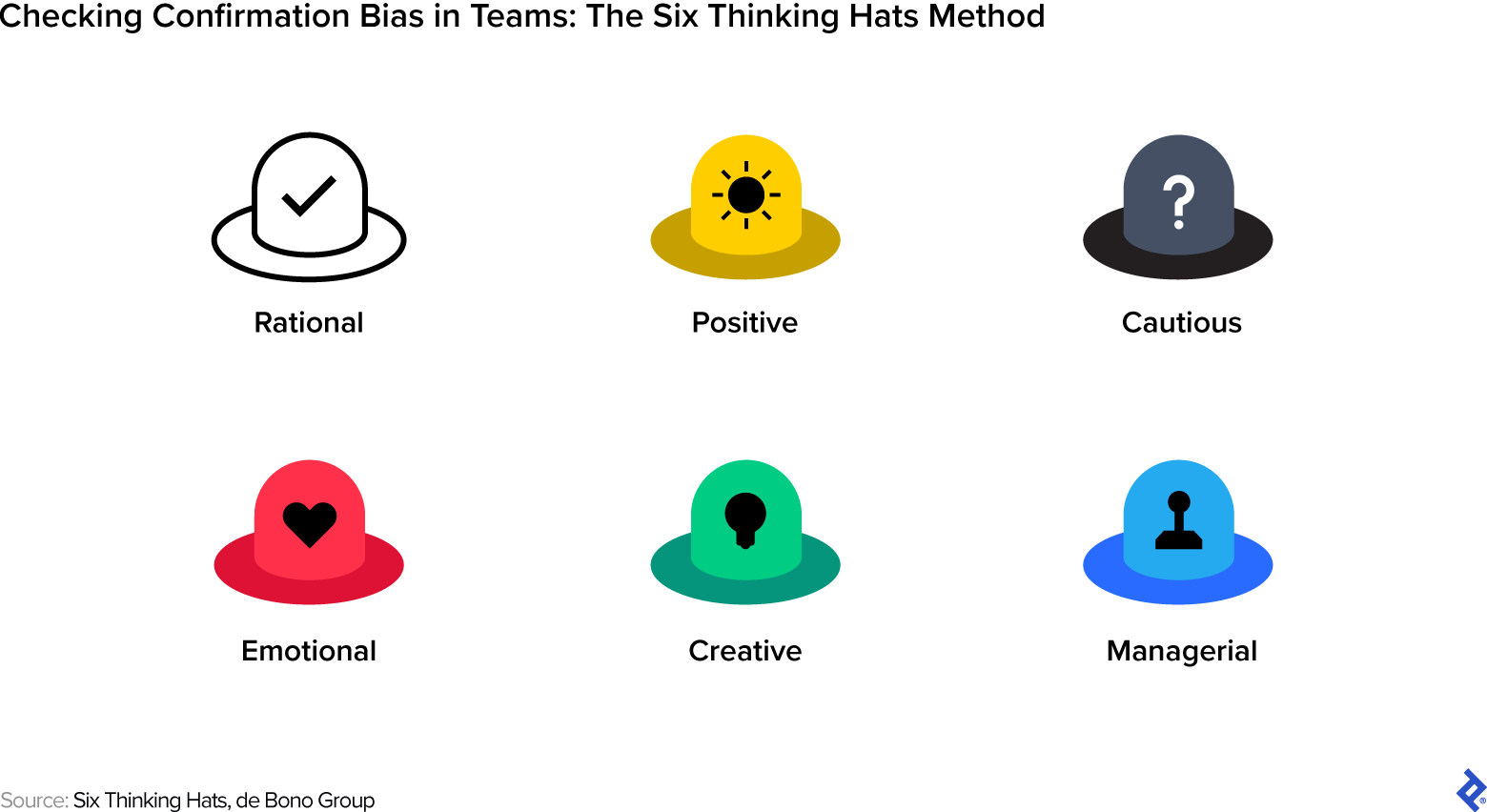

Another analysis method used to reduce confirmation bias is the Six Thinking Hats. Established by the de Bono Group, this method assigns each teammate one of six different personas during user research: rational, positive, cautious, emotional, creative, and managerial. Each of these roles is represented by a different color hat. For example, when the team leader assigns a member the green “creative” hat during a brainstorming session, that person is responsible for sharing outside-the-box solutions and unique perspectives. Meanwhile, the team member wearing the blue “managerial” hat would be in charge of observing and enforcing the de Bono methodology guidelines. The Six Thinking Hats method provides a checks and balances approach that allows teammates to identify one another’s errors and effectively fight cognitive biases.

Anchoring Effect: The Options Provided Can Skew Feedback

The anchoring effect can occur when the first piece of information a person learns about a situation guides the decision-making process. Anchoring influences many choices in day-to-day life. For instance, seeing that an item you want to buy has been discounted can make the lower price seem like a good deal—even if it’s more than you wanted to spend in the first place.

When it comes to user research, anchoring can—intentionally or unintentionally—influence the feedback users give. Imagine a multiple-choice question that asks the user to estimate how long it will take to complete a task—the options presented can limit the user’s thinking and guide them to choose a lower or higher estimate than they would have otherwise given. The anchoring effect can be particularly impactful when questionnaires ask about quantities, measurements, or other numerics.

Word choice and the way options are presented can help you reduce the negative effects of anchoring. If you are asking users about a specific metric, for example, you can allow them to enter their own estimates rather than providing them with options to choose from. If you must provide options, try using numeric ranges.

Because anchoring can also impact qualitative feedback, avoid leading questions that can set the tone for subsequent responses. Instead of asking, “How easy is this feature to use?” ask the user to describe their experience of using the feature.

Order Effect: How Options Are Presented Can Influence Choices

The order of options in a survey can impact responses, a reaction known as the order effect. People tend to choose the first or last option on a list because it’s either the first thing they notice or the last thing they remember; they may ignore or overlook the options in the middle. In a survey, the order effect can influence which answer or option participants select.

The order of the questions can also affect results. Participants could get fatigued and have less focus the further they get in the survey, or the order of questions could convey hints about the research objective that may influence the user’s choices. These factors can lead to user feedback that is less reflective of the true user experience.

Imagine your team is surveying the usability of a mobile application. When crafting the questionnaire, your team orders the questions based on how you intend for the user to navigate the app. It asks about the homepage and then, starting from the top and going down, it asks about the subpages in the navigation menu. But asking questions in this order may not yield useful feedback because it guides the user and doesn’t represent how they might navigate the app on their own.

To counteract the order effect, randomize the order of survey questions, thus diminishing the possibility of earlier questions influencing responses to later ones. You should also randomize the order of response options in multiple-choice questions to avoid skewing results.

Peak-end Rule: Recalling Certain Moments of an Experience More Than Others

Users assess their experiences based on how they feel at the peak and end of a journey, instead of assessing the entire encounter. This is known as the peak-end rule, and it may influence how research participants give feedback on a product or service. For example, if a user has a negative experience at the very end of their user journey, they may rate the entire experience negatively even if most of the process was smooth.

Consider a situation in which you are updating a mobile banking application that requires users to enter data to onboard. Initial feedback on the new design is negative and you’re worried you’re going to have to start from scratch. However, after digging deeper through user interviews, you find that participant feedback centers on an issue with one screen that refreshes after a minute of inactivity. Users usually need additional time to gather the information required for onboarding, and are understandably frustrated when they can’t progress, resulting in an overall negative perception of the app. By asking the right questions, you might learn that the rest of their interactions with the app are seamless—and you can now focus on addressing that single point of friction.

To get comprehensive feedback on questionnaires or surveys, ask about each step in the user journey so that the user can give all the elements equal attention. This approach will also help identify which step is most problematic for users. You can also group survey content into sections. For instance, one section may focus on questions about a tutorial while the next asks about an onboarding screen. Grouping helps the user process each feature. To mitigate the possibility of the order effect, randomize the questions within sections.

Observer-expectancy Effect: Influencing User Behavior

When the experimenter’s actions influence the user’s response, this is called the observer-expectancy effect. This bias yields inaccurate results that align more with the researcher’s predetermined expectations than the user’s thoughts or feelings.

Toptal designer Mariia Borysova observed—and helped to correct—this bias recently while overseeing junior designers for a healthtech company. The junior designers would ask users, “Does our product provide better health benefits when compared to other products you have tried?” and “How seamlessly does our product integrate into your existing healthcare routines?” These questions subtly directed participants to answer in alignment with the researcher’s expectations or beliefs about the product. Borysova helped the researchers reframe the questions to sound neutral and more open-ended. For instance, they rewrote the questions to say, “What are the health outcomes associated with our product compared to other programs you have tried?” and “Can you share your experiences integrating our product into your existing healthcare routines?” Compared to these more neutral alternatives, the researchers’ original questions led participants to perceive the product a certain way, which can lead to inaccurate or unreliable data.

To prevent your own opinions from guiding users’ responses, word your questions carefully. Use neutral language and check questions for assumptions; if you find any, reframe the questions to be more objective and open-ended. The observer-expectancy effect can also come into play when you provide instructions to participants at the beginning of a survey, interview, or user test. Be sure to craft instructions with the same attention to detail.

Safeguard User Research From Your Biases

Cognitive biases affect everyone. They are difficult to protect against because they are a natural part of our mental processes, but designers can take steps to mitigate bias in their research. It’s worth noting that cognitive shortcuts aren’t inherently bad, but by being aware of and counteracting them, researchers are more likely to collect reliable information during user research. The strategies presented here can help designers get accurate and actionable user feedback that will ultimately improve their products and create loyal returning customers.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is user bias?

User bias refers to foreseeable ways that cognitive biases can affect a user’s feedback about a product or service. Everyone is subject to cognitive bias, and both researchers and participants exhibit biases that can influence research results.

What are the types of user research bias?

There are several types of user research bias, including confirmation bias—in which researchers select data that aligns with their beliefs—and order effect, in which the order of questions affects the results. Other biases include the anchoring effect, the peak-end rule, and the observer-expectancy effect.

Yerevan, Armenia

Member since May 4, 2021

About the author

Rima is a product designer with expertise in UI/UX design, graphic design, digital marketing, and user research. She has worked across various industries to create user-focused and aesthetically pleasing digital products, and spent six years at the global software development company Volo.

Expertise

Previous Role

UX/UI DesignerPREVIOUSLY AT