How to Prepare a Cash Flow Statement Model That Actually Balances

When a cash flow statement model doesn’t balance, it can cause immense frustration and wasted time. The root cause of this problem most commonly resides in models being built with inconsistent and contradictory data sources.

When a cash flow statement model doesn’t balance, it can cause immense frustration and wasted time. The root cause of this problem most commonly resides in models being built with inconsistent and contradictory data sources.

Pierre has contributed to the completion of more than 30 M&A deals, specializing in the retail, SaaS, and technology spaces.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

To download the example cash flow statement used throughout this post, click here.

Whether I’m looking at acquisition opportunities at HoriZen Capital or building best practices models, I often see cash flow statements that don’t reconcile with the balance sheet.

The most common reason is the wide range of data sources used by the company: the sales teams’ tracking software, CapEx files maintained by the CFO, and inventory reporting metrics from the procurement team, to name a few. When something falls out of line between all these sources, it very quickly causes critical imbalances in a model.

I have worked on several financial due diligence projects for M&A deals where data provenance was a problem. First, it creates doubts and worries in the buyer’s mind: “How can we trust the accuracy of the numbers if different sources give different results?” This can be a dealbreaker or can taper confidence in the team’s ability to execute. Second, it creates unnecessary costs arising from the extra work required to dig out the missing pieces, generating extra labor hours on both sides of the transaction. All of this can be avoided by following a strict but simple methodology:

Build financial models with correct interconnectivity between the three primary accounting statements: income statement, balance sheet, and P&L.

Below is a step-by-step method to ensure your cash flow always balances and tallies. I will also explain the interconnectivity between the different lines of the cash flow statement and demonstrate why balance sheet accounts and, in particular, Net Working Capital have a central role in making it all work. To help your learning, I have also put together an example spreadsheet which demonstrates the required interconnectivity.

How to Prepare a Cash Flow Statement

There are two widespread ways to build a cash flow statement. The direct method uses actual cash inflows and outflows from the company’s operations, and the indirect method uses the P&L and balance sheet as a starting point. The latter is the most common method encountered since the direct method requires a granular level of reporting that can prove more cumbersome.

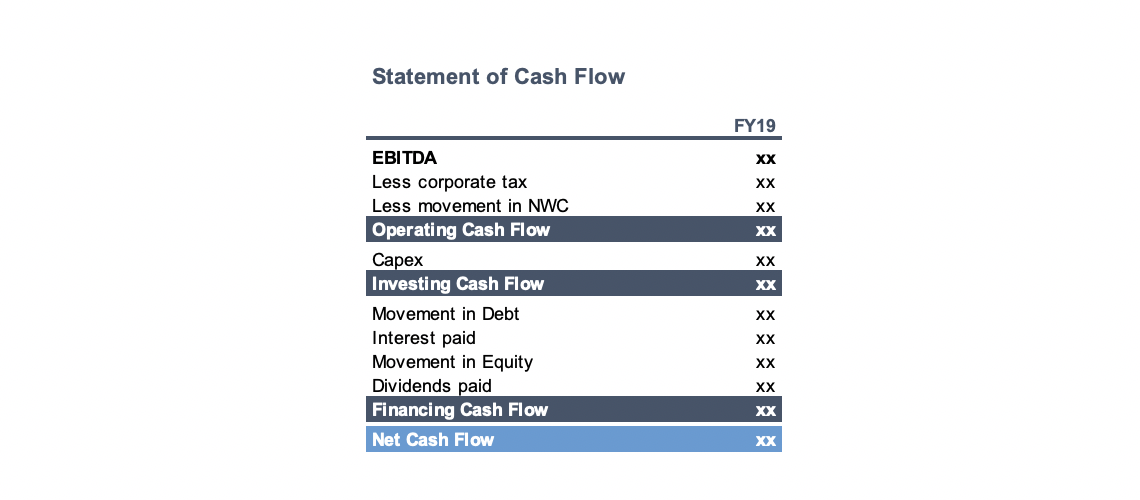

Below is a snapshot of what we aim to achieve. It may look straightforward, but each line represents a number of precedent calculations.

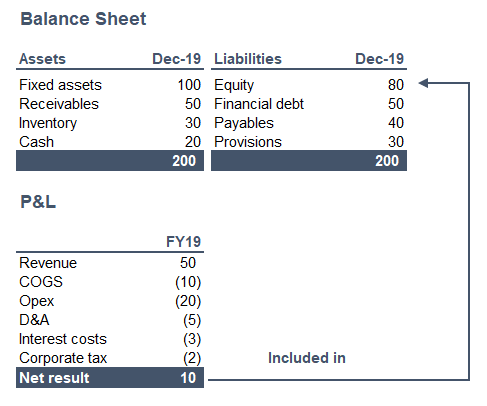

Step 1: Remember the Interconnectivity Between P&L and Balance Sheet

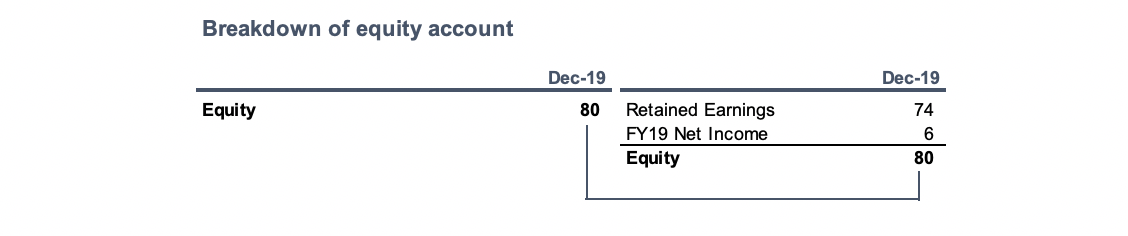

While basic, it’s worth reminding ourselves that total assets must always be equal to total liabilities (and equity). The P&L and balance sheet are interconnected via the equity account in the balance sheet. Any debit or credit to a P&L account will instantly impact the balance sheet through being booked on the retained earnings line.

Step 2: The Cash Account Can Be Expressed as a Sum and Subtraction of All Other Accounts

Due to the inalterable equality of total assets and total liabilities, we know that:

Fixed Assets + Receivables + Inventory + Cash = Equity + Financial Debt + Payables + Provisions

Basic arithmetic then allows us to deduce that:

Cash = Equity + Financial Debt + Payables + Provisions - Fixed Assets - Receivables - Inventory

This also means that the movement of cash (i.e., net cash flow) between two dates will be equal to the sum and subtraction of the movement (the delta) of all other accounts:

Net Cash Flow = Δ Cash = Δ Equity + Δ Financial Debt + Δ Payables + Δ Provisions – Δ Fixed Assets – Δ Receivables – Δ Inventory

Step 3: Break Down and Rearrange the Accounts

Equity

As discussed earlier, assuming that we are looking at a balance sheet before any payment of dividends, the equity account will include the current year’s net income. As such, we will have to break down the account more granularly to make the current year’s net income appear clearer.

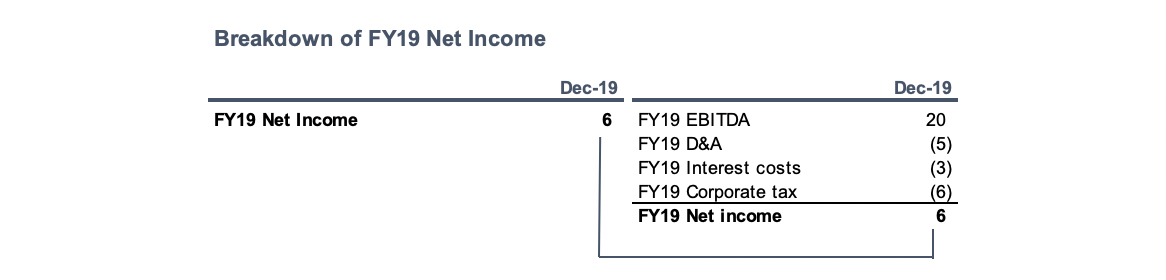

Net Income

The line item of net income is made of constituent parts: most prominently, EBITDA less depreciation and amortization (D&A), interest, and tax.

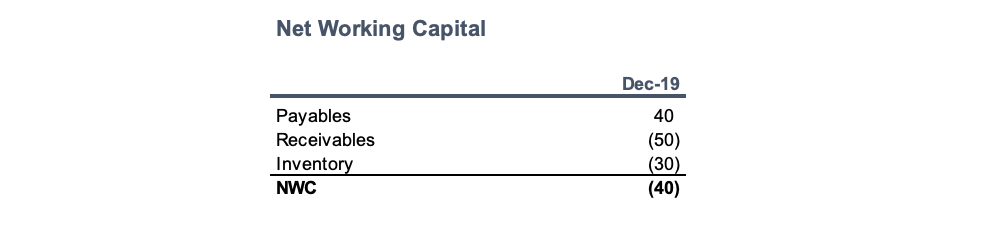

Net Working Capital Movements

Working capital comprises three elements: inventory and receivables on the asset side and payables on the liabilities. When netted off against one another, they subsequently equal the net working capital position, which is the day-to-day capital balance required for running the business.

It goes without saying that an increased balance movement on a working capital asset constitutes an outflow of cash, while the inverse applies to their liability counterparts.

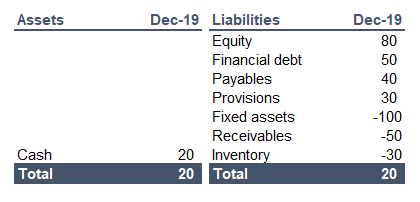

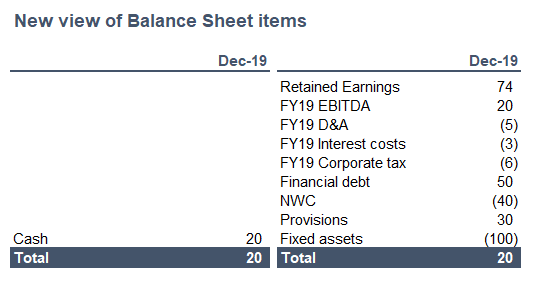

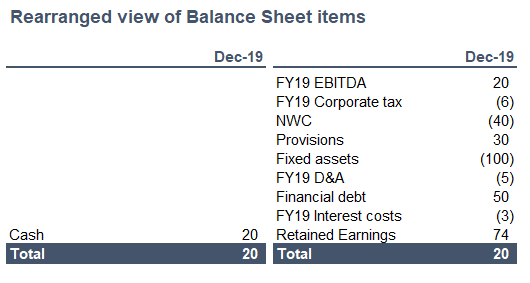

Put Together a New View of the Balance Sheet Items

If we aggregate all of the changes we have just made, they will come together in the following order:

To an accountant, this may look quite haphazard, so its best to re-order in a manner more like a traditional cash flow statement format:

Step 4: Convert the Rearranged Balance Sheet Into a Cash Flow Statement

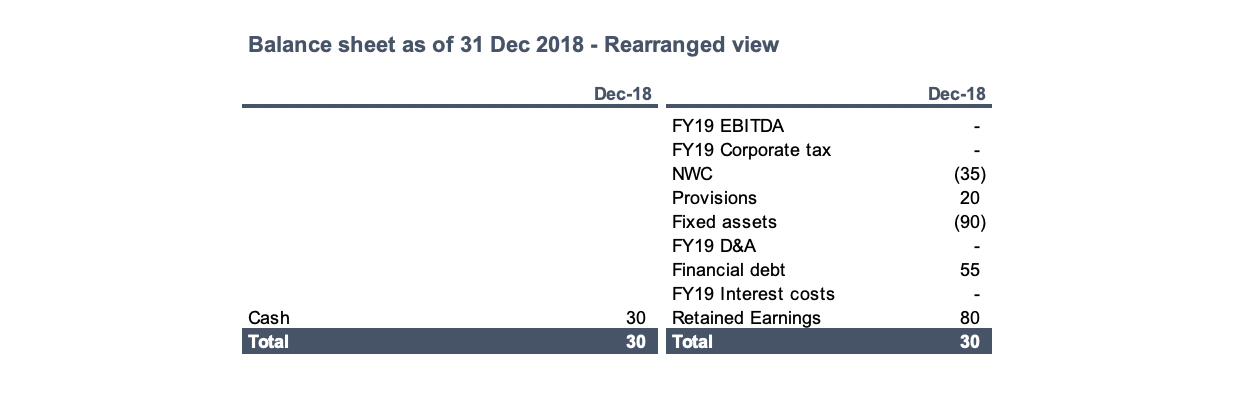

At this stage, you may notice that we have only been using one balance sheet position: a position at a fixed point in time (December 31, 2019 in our example). To calculate cash flow from here, we would need a second balance sheet at a different date. In this example, we will use the balance sheet below, which is dated December 31, 2018, before the distribution of FY18 dividends.

There are two points to consider here:

- As of Dec-18, the FY19 fiscal year had not started—therefore, all FY19 P&L-related accounts will be equal to zero.

- The retained earnings figure here will include the FY18 net income.

In order to calculate a statement of cash flows, we will need to look at the movements between Dec-19 and Dec-18. Thanks to the equality that we demonstrated in Step 2, we already know that the net cash flow will be equal to 20 - 30 = -10.

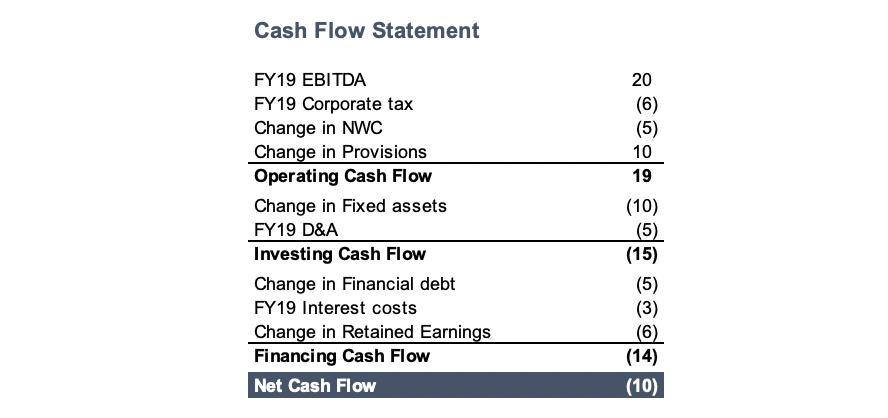

By simply taking the movement between the two balance sheets positions and adding subtotals for clarity of presentation, we have now created a dynamic and balanced cash flow statement:

How to Improve Your Cash Flow Statement Processes?

This is now the part where having classical accounting knowledge will prove useful, although it is not a prerequisite. The objective of creating a cash flow format like the one above is to better assess and understand the cash inflows and outflows of the business by their category (e.g., operating, financing, and investing). Now that you have a cash flow statement that links dynamically to the balance sheet, it’s time to dig a bit further. To do so, here are a few questions to ask yourself:

1. Are All Accounts Correctly Categorized?

This is quite a forensic exercise that will essentially require you to look over every line account used in your accounting software. Once analyzed, a discussion with the financial controller, or CFO, can then take place to question any discrepancies of opinion over the correct classification of items.

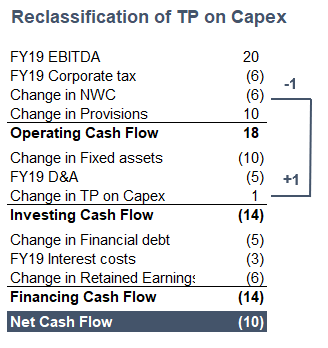

A classic example in this scenario is trade payables on CapEx (i.e., outstanding payments due to fixed asset providers). It is quite common that this account gets included in the trade payables (in current liabilities) and, as such, gets classified as net working capital. If this is the case, you will need to remove it from NWC and add it to the cash flows from the investing (CFI) section.

Assuming a movement of trade payables on CapEx of +1 between Dec-18 and Dec-19, we would make the following changes to our cash flow statement from the example above:

2. Is the Presentation Representative of Actual Cash Inflows and Outflows?

The notion of cash and non-cash can be quite confusing to the uninitiated. For example, if Company A sold an item for $40 that it purchased for $10 in cash last year, but its customer still has not paid for it, what should you consider “cash EBITDA”? Should it be $30 (revenue less COGS, assuming no other OpEx)? Or should it rather be $0 (considering that the item purchased was paid for last year and no proceeds have been collected yet)?

What people often miss is that NWC and EBITDA should be analyzed together when looking at cash generation. When EBITDA is impacted by a so-called “non-cash item,” remember that there is always a balance sheet account concomitantly impacted. Your responsibility as a cash flow builder is to understand which one. And the answer quite often lies within the accounts included inside net working capital!

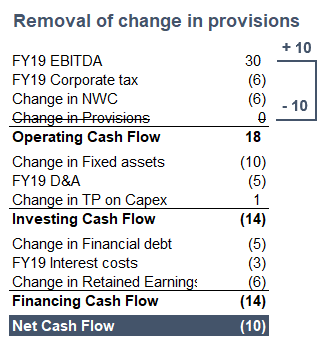

A common example of “non-cash items” are provisions. Let’s remember that provisions intend to impact today’s P&L in anticipation of a likely expense in the future. Based on that definition, it is safe to say that such an item has not truly had any cash implication over the fiscal year, and it would make sense to remove it from our cash flow statement.

In the P&L example we’ve used so far, it seems that provisions were booked above EBITDA. Hence, if we want to remove the impact of a change in the provision, here is how we could proceed:

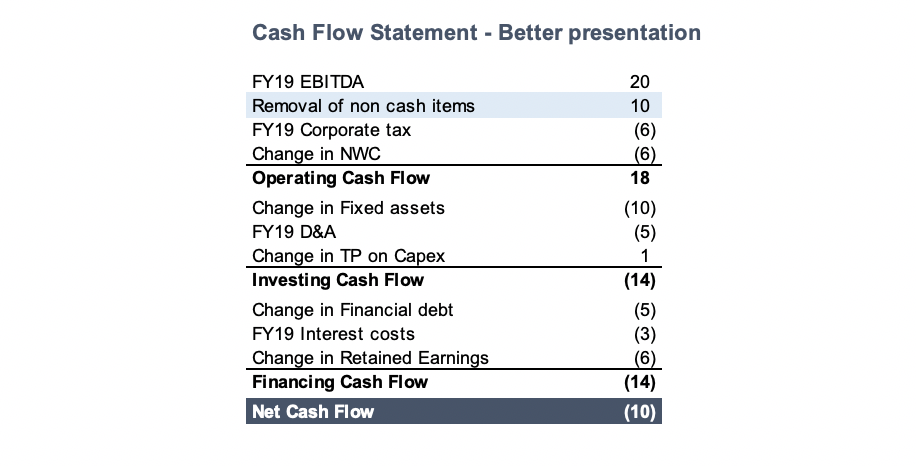

However, the issue we find with this presentation is that we would like FY19 EBITDA to reconcile to EBITDA as per the P&L. To that end, we would rather present our cash flow statement as follows:

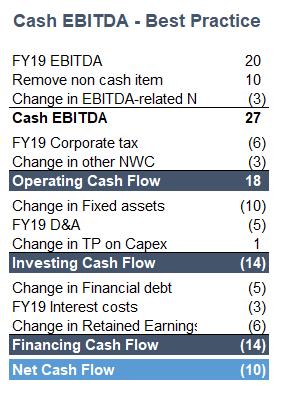

I would also recommend that you include a footnote explaining what the removed non-cash items were referring to. It may also be appropriate to showcase the “cash” EBITDA component of the business, which would comprise the following:

Obviously, this can get quite cumbersome, as it requires a correct match of all NWC accounts linked to EBITDA items. I don’t believe, though, that this added complexity gives a clearer view of the company’s cash-generative abilities, but it may help to at least provide your stakeholders with as much descriptive help to the numbers as possible.

Take the Rules and Apply Them Practically

I hope that this provides you with the tools to effectively create a cash flow statement and that you now have a clearer understanding of the interconnections between P&L and balance sheet accounts. Once you understand this methodology, it is up to you to rearrange the different accounts and present them in a way that makes the most sense for your particular needs and your particular business.

Of course, real-life applications may be slightly trickier due to the number of accounts in your trial balance, the complexity of accounting principles, and any exceptional events, like an M&A transaction, for example. However, the underlying principles I’ve used in this cash flow statement model remain exactly the same, and if followed thoroughly, will allow you to use your time proactively instead of pouring countless hours into a thankless balancing exercise!

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- Financial Clarity at Last: How to Reboot Your Chart of Accounts Structure in 7 Steps

- Forecast for Success: A Guide to Cash Management

- Advanced Financial Modeling Best Practices: Hacks for Intelligent, Error-free Modeling

- Cash Flow Optimization: How Small and Medium Businesses Can Unlock Value and Manage Risk

- Remote or On-site? The Real Cost of Office Space for a Venture-backed Startup

- Justifying Investments With the Capital Budgeting Process

- Strategic Financial Leadership: 6 Skills CFOs Need Now

Understanding the basics

What are the elements of a cash flow statement?

A cash flow statement comprises three parts: cash flow from operations, cash flow from investing, and cash flow from financing. As per their titles, they relate to the different uses of cash categorized by their purpose.

Pierre-Alexandre Heurtebize

Nantes, France

Member since January 9, 2020

About the author

Pierre has contributed to the completion of more than 30 M&A deals, specializing in the retail, SaaS, and technology spaces.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT