Corporate Venture Capital: The Devil...or an Innovative Growth Channel?

In industries seeing stagnant growth or a negative impact from uncontrollable, outside forces, many companies are turning to corporate venture capital as an alternative means to innovation. Yet, famed venture capitalist Fred Wilson once said that corporate venture capital was the “devil.”

In industries seeing stagnant growth or a negative impact from uncontrollable, outside forces, many companies are turning to corporate venture capital as an alternative means to innovation. Yet, famed venture capitalist Fred Wilson once said that corporate venture capital was the “devil.”

Elizabeth was an equity research analyst on both the buyside and sellside before transitioning to freelancing where she specializes in market research and valuation.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Fred Wilson, famed venture capitalist of Union Square Ventures, once said that he thought corporate venture capital was the “devil.”

“[Corporate investing] is dumb. I think corporations should buy companies. Investing in companies makes no sense. Don’t waste your money being a minority investor in something you don’t control. You’re a corporation! You want the asset? Buy it,” Wilson said at the CB Insights Future of Fintech Conference.

Essentially Wilson was saying that CVCs (corporate venture capital) were mostly for show: “Making a minority investment in something? What does that do? Make you look smart in front of your boss?”

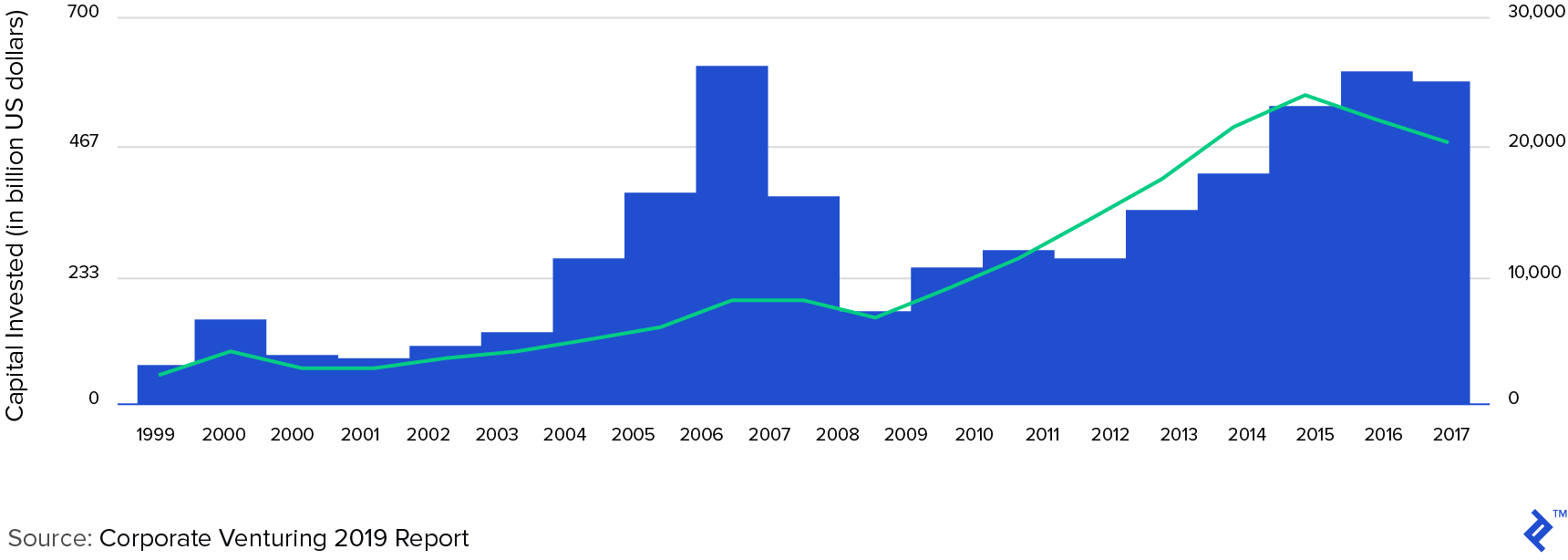

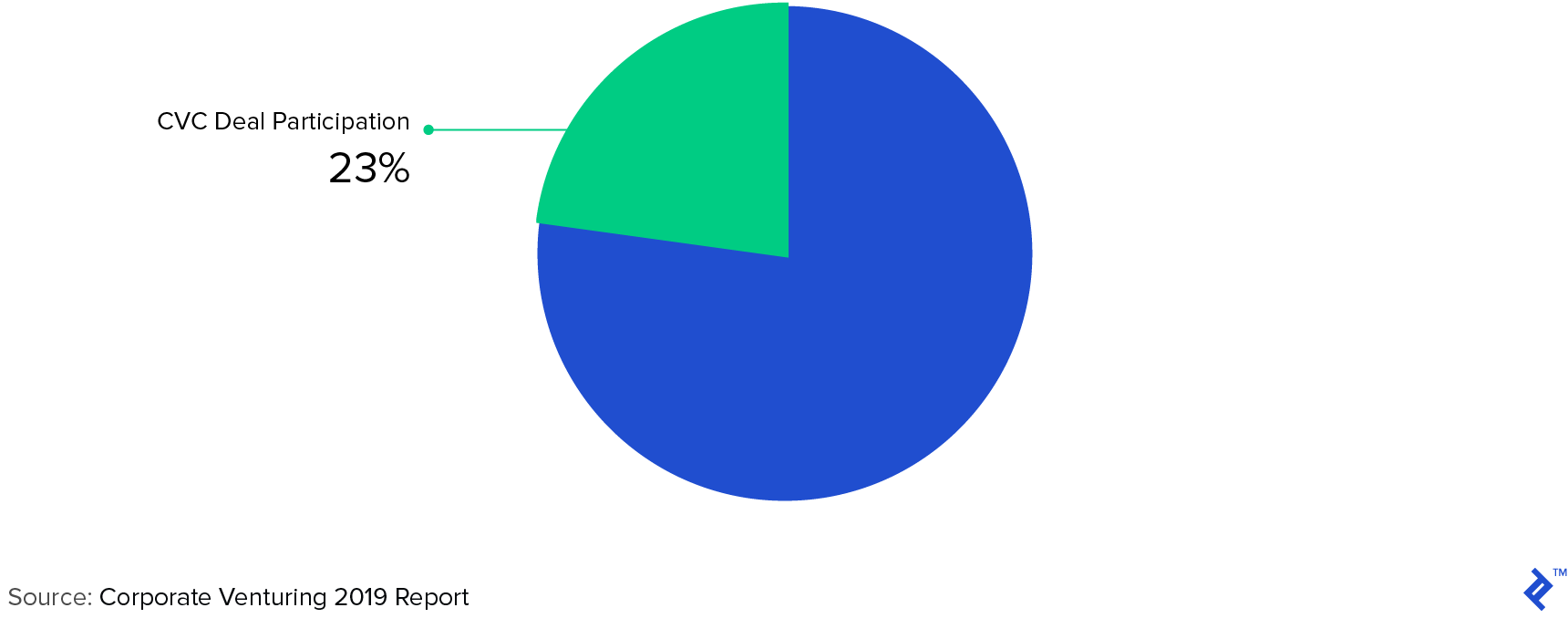

Yet, corporate venture capital is exploding. Active CVC business units rose to 773 in 2018, up 35% versus the prior year. Corporate VCs were involved in 23% of all investment deals in external startups in 2018.

While expected tech giants like Google, Intel, and Salesforce top the list of the most active and the highest dollar invested, other industries are joining the party. Somewhat recent non-tech entrants include Pearson (education), Shell (energy), Airbus (aerospace), Novartis (pharmaceutical), and Mitsubishi (mobility).

Is Wilson right? Or is he being a sore loser, unhappy with the increased competition for good deals?

For industries seeing stagnant growth or a negative impact from uncontrollable, outside forces, many are turning to corporate venture capital as an alternative means to innovation. I spoke with a handful of Toptal finance experts with CVC experience to get the inside scoop on whether CVCs are just smoke and mirrors or a legitimate growth avenue.

Why Does Corporate VC Make Any Sense?

A corporate VC is an independent arm of a company that allows them to take a small bet (own a % vs. the entire project) in a big idea and gives access to innovative and entrepreneurial talent. Corporate VCs are similar to traditional VCs in that they both tend to invest in high-growth, somewhat moonshot-type projects. CVCs, however, are considered to be more long-term focused than traditional VC.

Still, it is debatable whether CVCs actually focus more on strategic wins and innovation versus financial returns, and we’ll discuss the issue further below in How to Get Corporate VC Right.

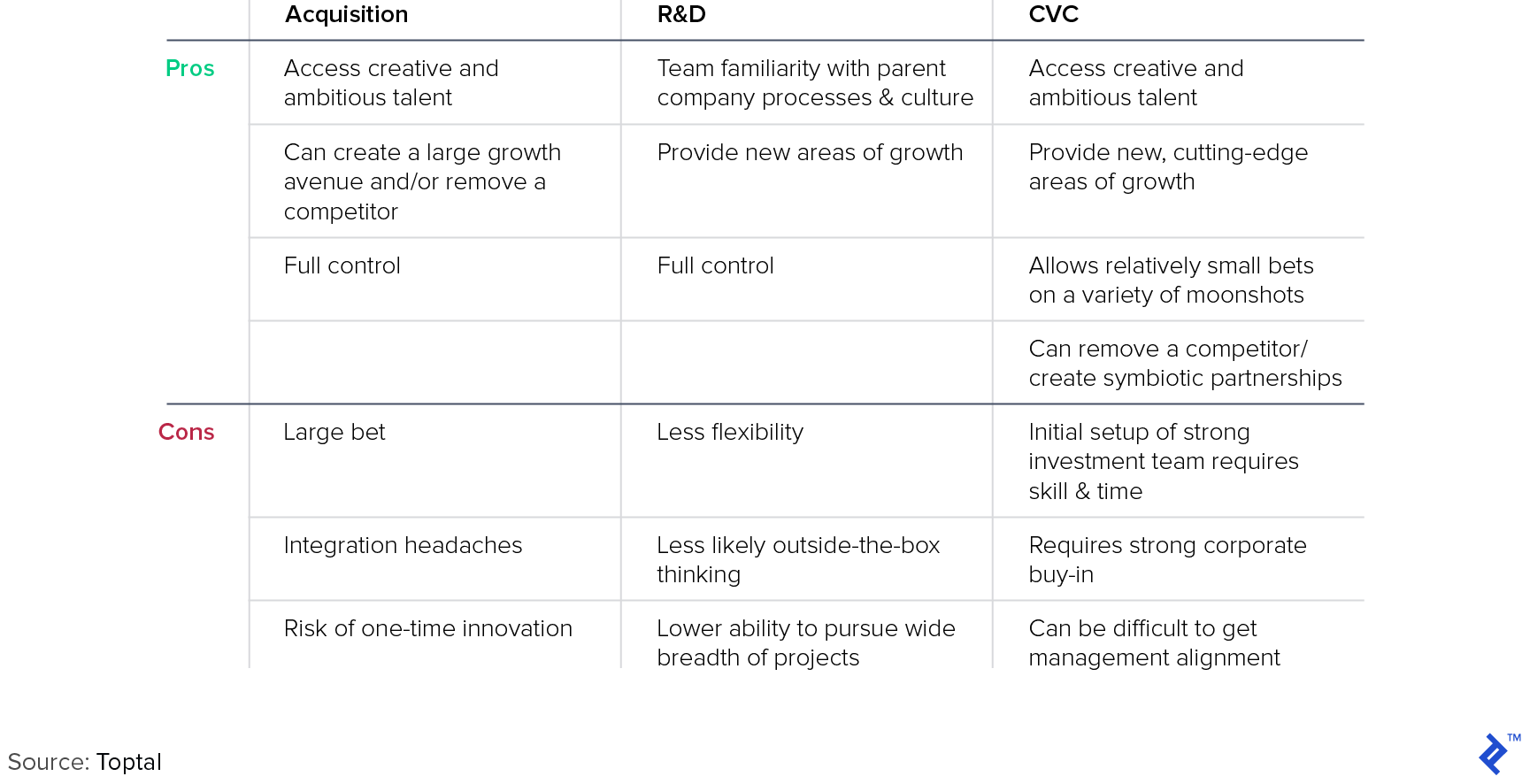

But why do corporations invest in these VC arms rather than just R&D, or go all-in with a full-on acquisition?

CVC Can Uncover Growth Avenues with Minimal Commitment

Because companies can invest their CVCs off the balance sheet (usually), it gives them more scale in research & development (R&D) than just the P&L allows. At the same time, companies are able to access creative and ambitious talent they can’t usually find in the corporate world. Furthermore, companies can make small bets in a variety of moonshot projects instead of owning the entire project—as a company would need to do if they were entirely responsible for the project with their own research and development dollars.

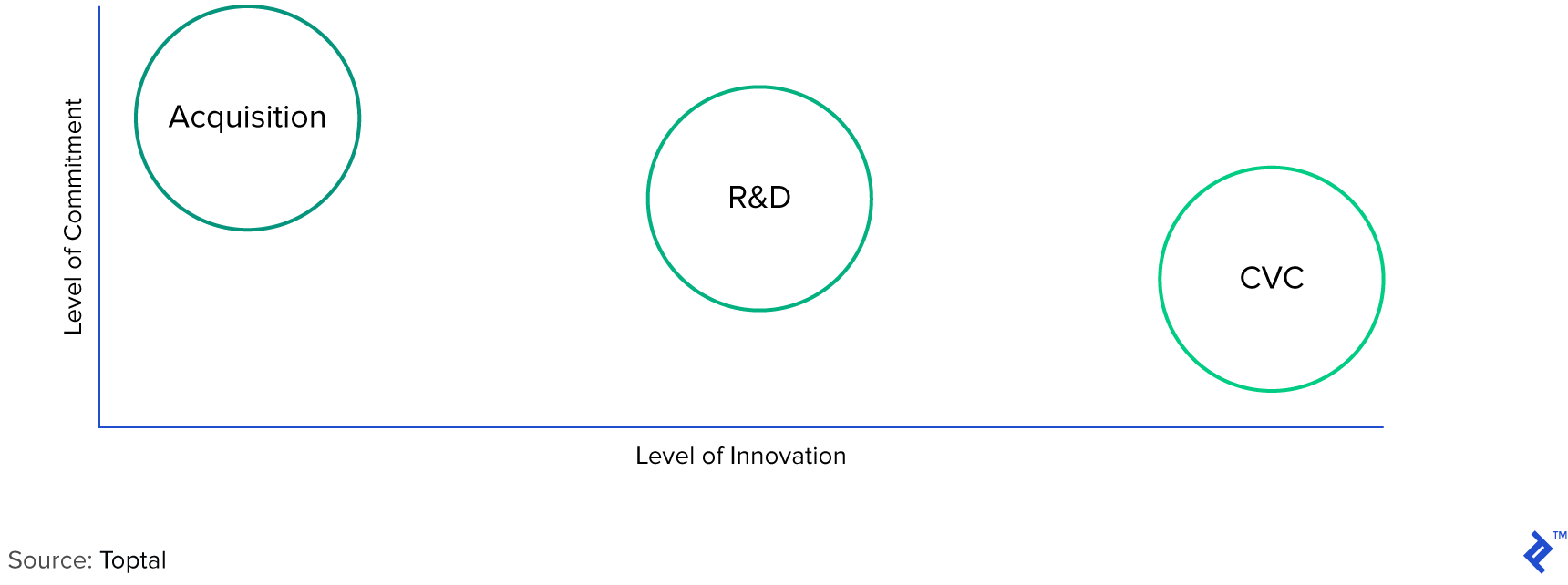

While the graph below is perhaps an oversimplification, and the exact “level of commitment” between R&D and CVC can be debated, it provides a relative idea of how much bang for your buck each innovation channel provides.

Acquisition vs. R&D vs. Corporate VC

The chart below is an oversimplification of acquisition vs. R&D vs. CVC. There are nuances that could make an acquisition strategy quite innovative and not high on the commitment level (e.g., a serial outright acquirer of small, cutting-edge companies). However, we created this chart to help categorize the most common ways these strategies work out.

We’ve also caveated the chart to simply show the “first interaction,” meaning that this doesn’t capture what would happen if a CVC turned its partial investment into a full-blown acquisition. In that case, it’s a bit subjective and idiosyncratic where the strategy would fall on our spectrum.

An acquisition is the most amount of commitment to a project a company can give. Once you acquire a company, there’s generally no “backsies” if you don’t like what you get. However, once that company is acquired, unless it’s an acqui-hire wherein you’re really just hiring talent, the level of future innovation for the core company is relatively low. Usually, an acquisition is done to expand breadth or to delve deeper into a currently served market; however, it is a one-time event.

With Research & Development, you have some flexibility in commitment. You have a team of R&D experts who are focused on whatever projects the company deems important. You can pull people off certain projects and put them on others. But what about when you want to explore something your current R&D experts are not experts in? Toptal Venture Capital expert Alex Graham noted a strong reason why big, out-of-the-box innovation is unlikely to happen with a company’s existing R&D team: “You don’t want to innovate yourself out of a job.” Yet, within a certain spectrum of innovation, internal R&D can be successful in that they know the corporate culture and they know their customer. Apple and Netflix are good examples of successful, innovative internal R&D.

Corporate Venture Capital arguably provides the lowest level of commitment with the highest level of innovation. The commitment level is low in that you don’t need to buy an entire company or staff your entire R&D team on one project, however, it is not nil as you need to invest in the actual setup of the CVC itself. It’s worth noting that an investment by a CVC arm could eventually lead to a full-on acquisition. The initial corporate venture capital investment allows some level of access to financials, a greater understanding of the pros and cons of the business (versus coming in cold without a prior relationship), and access to a younger company likely innovating to solve a newer problem.

The level of innovation in CVC is at the higher end of the spectrum as it allows access to a plethora of new ideas formed by young, nimble companies solving problems that haven’t been solved before.

Toptal Venture Capital expert Khaled Amer saw this in action while working as an analyst at Vodafone Ventures: “A CVC brings a fresh perspective into the areas of innovation. As a telecom company, we thought ‘How can we grow into IoT?’, ‘How can we increase data consumption by providing them with digital media content via different websites and apps?’ We needed to innovate out of the core business.”

Amer elaborated on Vodafone’s reasons for exploring CVC as an innovative growth channel: “Vodafone is a big telecom company. We were doing big numbers with high profitability but the growth matured significantly in recent years. The reason we went to CVC was to innovate out of our core business and to try to have better topline growth.”

Corporate VCs are all about improving the parent company’s strategic position (as opposed to traditional VCs, which tend to focus on financial payoffs). The parent realizes they can’t match the innovation breakthrough ability of a young, agile startup, so they use their own inhouse VC to get ahead of the competition and get a piece of that “nimbleness.” Steven Southwick, a Toptal finance expert and CEO of Pointful Education, described how he sees this happening in the education space: “Pearson Ventures gives Pearson the ability to have the first look at new ideas coming through the door and the ability to acquire or invest in the ones that look most promising.”

Pearson, the British education conglomerate, recently committed $50 million to its Pearson Ventures with the statement, “Because education will look very different in 2030, Pearson, like learners all over the world, will need to continue to learn, adapt and reinvent itself: finding new business models, incorporating emerging technologies into its products and services, and finding new ways to collaborate with education institutions, government, and businesses.”

CVC: On-balance Sheet vs. Off-balance Sheet - Another Nuance

It’s also worth noting that we could break CVC down further into two types: on-balance sheet and off-balance sheet. An off-balance sheet CVC would be furthest to the right in the graph above, while an on-balance sheet would be just a bit to the left (but still to the right of R&D). Toptal Venture Capital expert Natasha Ketabchi notes: “Items which are on a company’s balance sheet must be very closely related to a company’s core business directive; if a CVC is held off of the balance sheet, it grants the company more freedom in its venture portfolio.”

How to Get Corporate VC Right

A lot of corporate VCs get it wrong and prove Wilson right. But there are three areas that our experts unanimously agreed upon as being key to a successful corporate venture capital.

-

A well-defined mission

One of the Toptal finance experts I spoke with who had been a part of a CVC noted that it was hard to confidently make investment decisions as their mandate was not crystal clear. They were never sure if their purpose was truly to innovate or to improve financial returns.

According to Toptal Venture Capital expert Aaron Chockla, “CVCs have more of the corporate culture bred into them and can be more long-term focused—thinking out 10, 20 years. In my experience, I’ve found CVCs can be a bit more mission-driven than traditional VCs, which aim to be long-term focused but oftentimes look at investments on a shorter horizon.”

Given the importance of mission versus short-term financial gains, it’s critical that the corporate parent spells out what exactly the mission is. The mission can be financially related (e.g., improve our long-term growth rate) but it needs to be tied to a higher purpose.

-

Full corporate commitment

Full corporate commitment is vital and often one of the most lacking features of CVC. With a corporate VC, there are a lot of stakeholders to manage. Without a corporate buy-in from the top, there is not a trusting relationship with portfolio companies, and that translates quickly.

One of the former CVC analysts I spoke with recalled how the parent company was not prepared for the failure of a portfolio company. When the portfolio company went out of business, this was considered by top management as “bad publicity.” For anyone familiar with VC, failures should surely be expected.

-

Alignment of compensation schemes

Many experts I spoke with noted the lack of compensation scheme alignment in corporate VC funds. CVCs often don’t allow their teams to participate in the upside the way that traditional VCs do with the “2 and 20” model—referring to the management fee and the performance fee, respectively, i.e., there is a 2% fee on the value of assets under management as well as a 20% incentive fee on performance above a certain benchmark. This is the traditional “eat what you kill model.”

However, in Corporate VC, it is not unusual to find teams that are compensated similarly to their R&D colleagues—i.e., they are salaried. Sometimes, CVCs will offer a bonus but the direct correlation with performance is not there as it is with traditional VC. Tying the CVC team’s compensation to the performance of their investment decisions would create proper alignment and motivation among all stakeholders.

Innovation vs. Chest-beating

When done correctly, Corporate VC can be an exhilarating way for companies to stay ahead of the competition. When done incorrectly, Wilson might be right: CVCs may have “devil”ish tendencies. Or perhaps, overzealous founders intent on world domination, one wave pool at a time.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is the role of corporate venture capital?

Corporate venture capital allows companies to take small bets on innovative companies.

Why do corporate venture capital funds fail?

Corporate venture capital funds often fail for three reasons: 1) The mission is not well-defined; 2) It doesn’t have full corporate commitment; and 3) There is not proper alignment of compensation schemes.

What are the differences between corporate venturing and new product development?

Both are channels of growth and innovation. New product development often happens with internal R&D teams, which may find it challenging to innovate outside of their expertise. Corporate venture capital allows access to teams with new areas of expertise.

Elizabeth J. Howell Hanano, CFA

Annapolis, MD, United States

Member since August 21, 2017

About the author

Elizabeth was an equity research analyst on both the buyside and sellside before transitioning to freelancing where she specializes in market research and valuation.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT