Embracing an “Aha!” Moment: Building Trust to Effect Change

What happens when you have a big idea but not the authority to make it happen? Earning trust is the key to influencing without authority.

What happens when you have a big idea but not the authority to make it happen? Earning trust is the key to influencing without authority.

Jerry has extensive experience working in organizational governance, digital and IT asset management, marketing analysis, and e-commerce.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

As product managers, we are always looking for that game-changing factor that will make our products unique and compelling. During the course of product development, we might come across a feature, a function, or a marketing angle that has not been prioritized—but should be. Unfortunately, in our position, we can’t mandate that this change be made; instead, we occupy a tough-to-navigate “influence without authority” space in our organizations. So if we’re lucky enough to have one of these “Aha!” moments, how do we get everyone else on board?

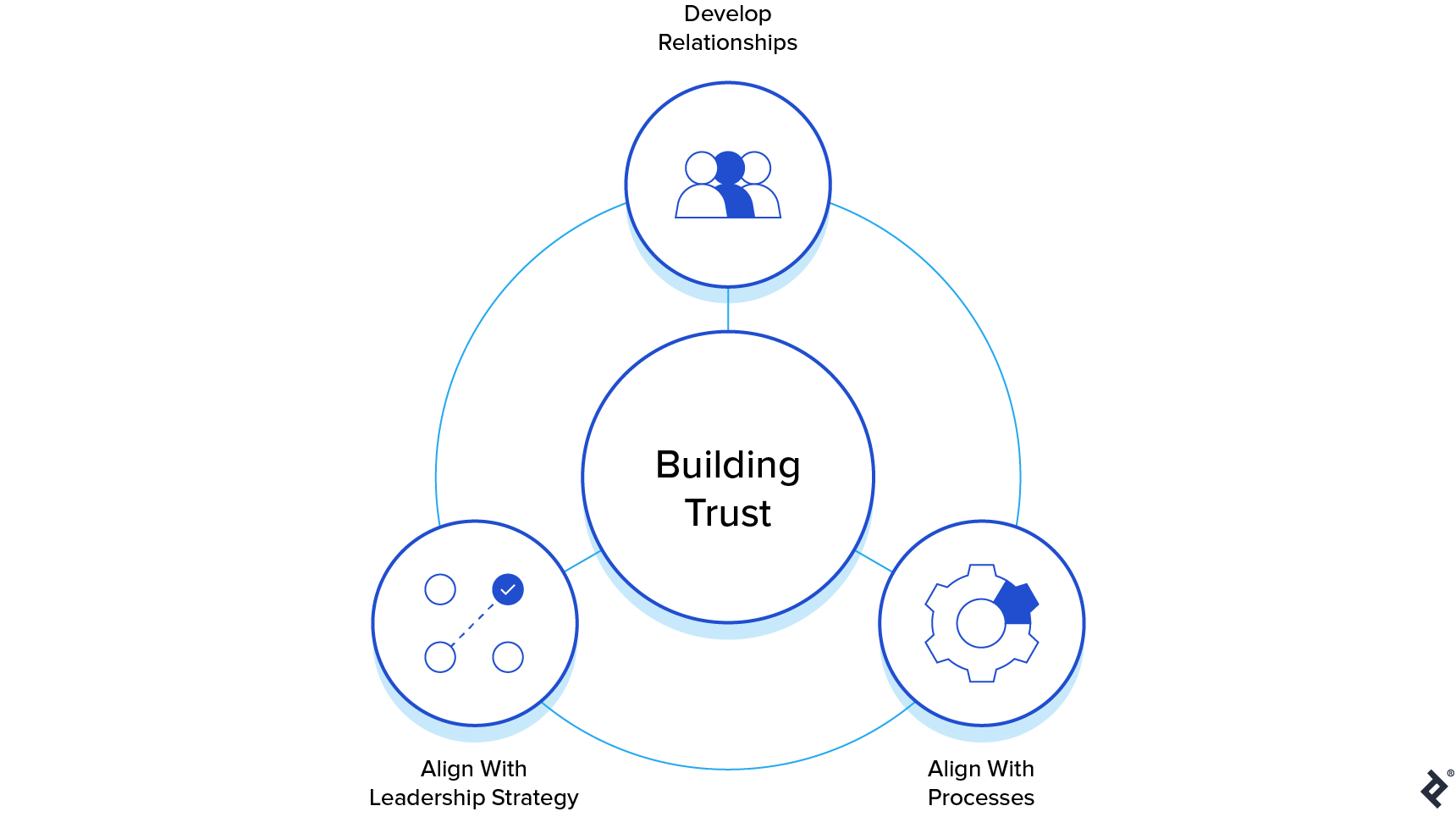

To lead successfully as a product manager, you have to start with solid arguments based on good data. To then sell those arguments and lead without authority, you need to develop trust, which allows both peers and company leaders to feel confident in following your suggestions. Building that trust boils down to three things: aligning with your organization’s leadership strategy, aligning with your organization’s processes, and developing relationships that let you turn your experience and expertise into real change.

Recognizing an “Aha!” Moment

Not long ago, I conducted a round of interviews with users of a product I managed. The product was a well-established SaaS document solution for governance meetings that digitized the hefty collection of contracts, graphs, letters, and other documentation that board members needed to review prior to meetings. These items were previously contained in the “board book,” which support staff would have to spend an enormous amount of time and energy compiling, sorting, copying, binding, and distributing—and then revising, when necessary—ahead of a meeting.

During the course of user interviews, I spoke to a woman whose personal experience with our product captured the essence of its value proposition. She was an executive assistant who had been doing the bulk of the work putting together the hard copy of the board book.

“You have no idea how it’s impacted my life,” she said of our document solution. “I’m no longer the last car in the parking lot.” Our system allowed her to get home to her family sooner on the busy nights before board meetings.

My discussion with her revealed a powerful emotional connection to the product that we hadn’t previously considered. Even more important than the feedback itself, however, was the person offering it. Making the board book process easier was the primary aim of our product but administrative and executive assistants were considered users—not targeted customers. As a company, we had been aiming all of our marketing and sales efforts at those who would pull the trigger on purchases—chairmen, board members, and IT leaders—not at the people who could most effectively persuade them of our product’s value: the assistants whose evenings at home we would be saving.

Turning “Aha!” Into Opportunity

Before embarking on a mission to gain support for what was now a burgeoning idea, I needed to be sure my thinking was sound. I conducted interviews with members of the board, who revealed how much they relied on their support staff. The executive assistant I talked to, in particular, was an influential member of the team whose work was valued immensely. It became clear during this second round of interviews that emphasizing the product’s impact on a board’s support staff could be a new factor in the purchasing process.

Making the shift to include administrative assistants in our customer directives, however, would mean that our company would have to create new communications and designs, make additional budget allowances, and introduce changes throughout sales. Persona portfolios—the user templates and descriptions we use for training—would need to be built, and we would need to classify this new group as influencers. As part of this, I felt it was essential to emphasize that our product was more than a tool to perform work; it also provided real emotional value to the user.

These changes would require significant adjustments on the part of multiple functions, and I knew I’d have my work cut out for me if I wanted to convince stakeholders to adopt a new approach. In order to lead everyone in the right direction without the authority to compel them to follow, I would need to establish myself as a trusted decision-maker.

Aligning With Leadership

If you want to gain the trust of executive leadership, demonstrate that the changes you want to make to the product’s roadmap, feature prioritization, and development mirror their strategic direction and goals. For example, users might tell you that they want new features that improve functionality, but the company’s focus might be on cutting costs. Flooding development with a list of new features to build would thus come into conflict with organizational priorities.

In the case of our board book product, I’m not suggesting that executive leadership had not previously considered how it would affect support staff. After all, the product was designed for support staff to use but messaging had been focused on upper management. So, in order to redirect our efforts to include a persona of the new influencer, I couldn’t just focus on that one emotional conversation I had with the executive assistant; my argument had to augment—not alter—our company leadership’s direction. I had to sell the change as the remedy of an oversight that wouldn’t create a new problem that was out of scope.

Aligning With Processes

In order to effect change, you need to know how your company operates. This includes knowing budget cycles and processes, understanding how projects are prioritized, and having an intimate knowledge of cross-departmental initiatives and procedures. As product managers, we might find ourselves as passengers on the ship, but if we want to influence and lead, it’s not merely enough to know where the captain and the other officers on the bridge are headed. We also have to have an intimate understanding of how the boat is steered.

Our board book product was one of many services we offered board members and their organizations, so in order to effect the change I wanted, I needed to identify our key decision-makers across divisions and talk to them about their visions for our success:

- I asked to be invited to the sales team’s meetings. I learned which conferences they attended and how their team prioritized those events. This allowed me to plan ahead and create a list of conferences that included the group of users I wanted to target and then research avenues such as LinkedIn Groups to find customer leads to reach out to prior to those events.

- I approached our communications and marketing departments, and asked to use their persona profiles so that I could present the new group I wanted to target in a way that fluently spoke the company’s language.

- I met with people in our project management office to learn the time frame I had to work in.

Reaching out across the organization, I broadened my knowledge of our product and other services. In the course of staying in touch with a wide range of departments on a regular basis, I learned what feedback they received and when they received it, which is also a brilliant way of staying aligned with leadership. Interacting with coworkers outside of your own immediate team also gives you the opportunity to share a bit of your experience and lay the groundwork for building personal trust.

Developing Relationships

Doing all this extra legwork gives you the background and knowledge you need to effect change, but it also builds friendships and valuable personal connections along the way. Knowing who has the authority to do what in your organization won’t get you very far if you don’t also develop strong relationships with those people.

Reach out to your colleagues and ask them about their lives even when you don’t need something. Offer positive, constructive feedback. Remember that the ability to handle other people’s emotions gently and intelligently while helping them grow in their jobs is a sign of great leadership. When someone does a good job, don’t be shy about telling them, their supervisors, and other team members. Being a good leader is about helping people to feel appreciated, so recognize their efforts personally and publicly.

Growing these relationships also leads to more opportunities to master the organizational ins and outs, creating a virtuous cycle. Stronger connections will allow you to get involved with companywide projects and initiatives, for example. All of this work may be outside the scope of your position as the team’s product manager, but the extra effort will be rewarded by the trust people place in you and their willingness to follow your guidance going forward. As you foster these relationships, be open to learning and then to recalibrating your ideas.

Translating Trust Into Change

In my quest to update our product strategy, I shared my ideas but didn’t push for the change I wanted to see right away. While I kept all communication lines open, I focused first on those team members who proved most receptive and explored what would change their minds. In doing this, I learned which information and data points were most persuasive and identified gaps in my own analysis. From there, I branched out to other coworkers, expanding my influence and getting more people involved in my plan.

After several months, I was presented with an opportunity to go to another company. By that time, marketing was beginning work on the new persona I had advocated for, and sales was planning to attend administrative conferences to push the new product direction. It was difficult to shift gears just as I was seeing my initiatives take off, but it was also an important reminder that everyone needs to remain flexible in order to foster a culture that supports positive change. Be open to new ideas and new points of view, support others in their efforts to bring change aligned with the organization’s goals, and be ready to start all over again … because change never stops.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

How do you influence when you don't have authority?

To successfully lead without authority, you need to develop trust, which allows others to feel confident in following your suggestions. To build that trust, you need to develop strong relationships and align with your organization’s leadership strategy and processes.

What are product managers responsible for?

Product managers are responsible for guiding the successful development and improvement of products for their companies. They work across divisions on business, marketing, research, and development initiatives.

What are the challenges of product management?

Product managers face a lot of challenges, but here are some of the most crucial: They need to ensure that product strategy is forward-looking and not reactive, that their team’s development priorities are properly defined, and that the company doesn’t waste time and effort on unnecessary or unwanted features.

How challenging are the roles of product manager?

Product managers are faced with a broad range of challenges as they attempt to develop successful products and deliver them to market. Their roles require extensive business and technical knowledge, strategic thinking, and excellent communication and interpersonal skills.

Jerry Gutierrez

San Antonio, TX, United States

Member since November 18, 2020

About the author

Jerry has extensive experience working in organizational governance, digital and IT asset management, marketing analysis, and e-commerce.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT