Why Market Share Is Important: Because Bigger Is Better Than Better

Product leaders have been force-fed the notion that market leadership is a function of delivering the best client experience. And yet, overperforming product managers focus first on being bigger, not better.

Product leaders have been force-fed the notion that market leadership is a function of delivering the best client experience. And yet, overperforming product managers focus first on being bigger, not better.

A former software engineer and analytics expert, Eric built a $1.2 billion network and security business from scratch.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

“Why did your products underperform?” Answering this simple question is uncomfortable for any product leader. Often, the ensuing conversation revolves around competitors, missed IT deadlines, wrong incentives, insufficient sponsorships, or slow adoption rates.

While external factors certainly contribute, for seasoned managers, these hurdles are “business as usual.” They actively address issues during development, but their diligent efforts can still produce underwhelming results. Successful leaders are constantly thinking about creating impact. They recognize that their product is not “the thing” but a means to a desired end result. Overperforming product managers usually display the following mindset:

I focus first on being bigger, not better.

Product leaders have been force-fed the notion that market leadership is a function of delivering the best client experience. Many programs guided by this mantra underachieve expectations—usually because they are incorrectly framing their definition of “best experience.”

Consider a local grocery chain adding an online ordering service with a drive-up/pickup service. Their differentiator might be employee “pickers” extensively trained to (a) identify the freshest produce and (b) proactively suggest cost-saving alternatives. Why then does this super consumer-friendly experience attract only a fraction of the number of shoppers willing to drive miles further to use a generic service from a nationwide superstore? Sometimes, when it comes to market share strategy, the advantages of being bigger can’t be overcome by being better.

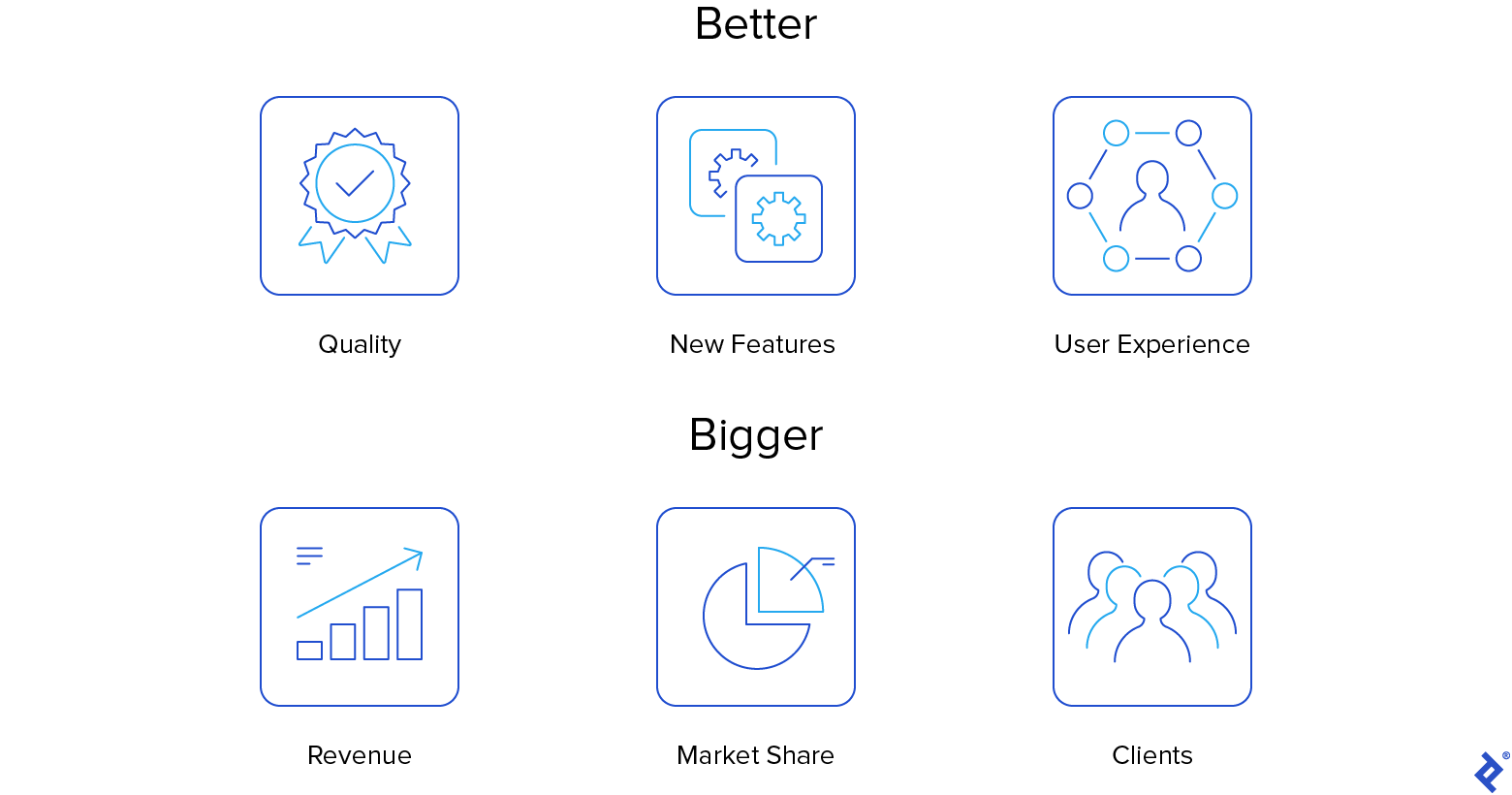

Bigger vs. Better

Better is associated with improving the ways in which clients learn, buy, use, and pay for a service. This includes all components of the end-to-end experience. A better offering might result from adding mobile app ordering, a more intuitive user interface, predictive shopping lists, or automating back-office service delivery.

In contrast, bigger refers to growing market share, adding subscribers, increasing revenues, and improving margins. Most product managers intuitively believe that better services lead to bigger results, but the reality is that the cause and effect correlation is much more complex.

Chasing Feature Parity Is Misleading

Product teams track results to a forecast or profit and loss (P&L) objective. They monitor client satisfaction surveys and service-level objectives. Corrective actions are initiated when metrics are not trending to expectations. Too often, the quick fix is an urgent scramble to address feature gaps based on anecdotal evidence from the sales teams of a big deal allegedly lost because a competing product had more capabilities.

Relying on this data is dangerous because it fails to consider whether functionality was the true reason for the purported loss. Often, a missing feature provides an easy way for a prospect to justify their alternate buying decision when a competitor simply offered a better overall value proposition. They cultivated stronger relationships, had established contracts that could be reused, bundled more components together, and provided other tangible or intangible benefits valuable to the buyer.

Continuing the example above, consumers shop at supermarkets even when they genuinely enjoy the personalized service of a neighborhood grocer because the overarching value derived from shopping at the box store exceeds the benefits realized from superior individual products or services.

In a similar way, product managers underestimate the importance of becoming superstore-like. “Becoming a superstore” is not necessarily about economies of scale. Instead, it is about creating a value ecosystem in which sales teams are motivated to promote your offerings more than other products, and clients have become so loyal that they check first with your company when seeking solutions to a new problem. The first stop for many consumers buying almost anything is Amazon. This phenomenon has less to do with low costs and more to do with trust, access to competing offers, fast delivery, and easy returns. Clients are biased toward market ecosystems that offer high levels of comfort and trust.

Enabling Salespeople vs. Building Features

Product managers almost exclusively focus on end clients when crafting products and don’t consider the needs of the sales team. Too often, managers rely on the perceived “greatness” of an offering to sell itself. They thus become reluctant to take drastic steps with early clients, preferring to spend months validating their original cookie-cutter concept while the market moves forward without them. Product managers aren’t investing enough into creating trusted ecosystems in which account teams want to sell products because they:

- Sense the company’s passion for the service

- Know the company will be responsive

- Know the company is willing to directly engage with clients

- Know the company will change direction based on feedback from the field

The Trap of the MVP

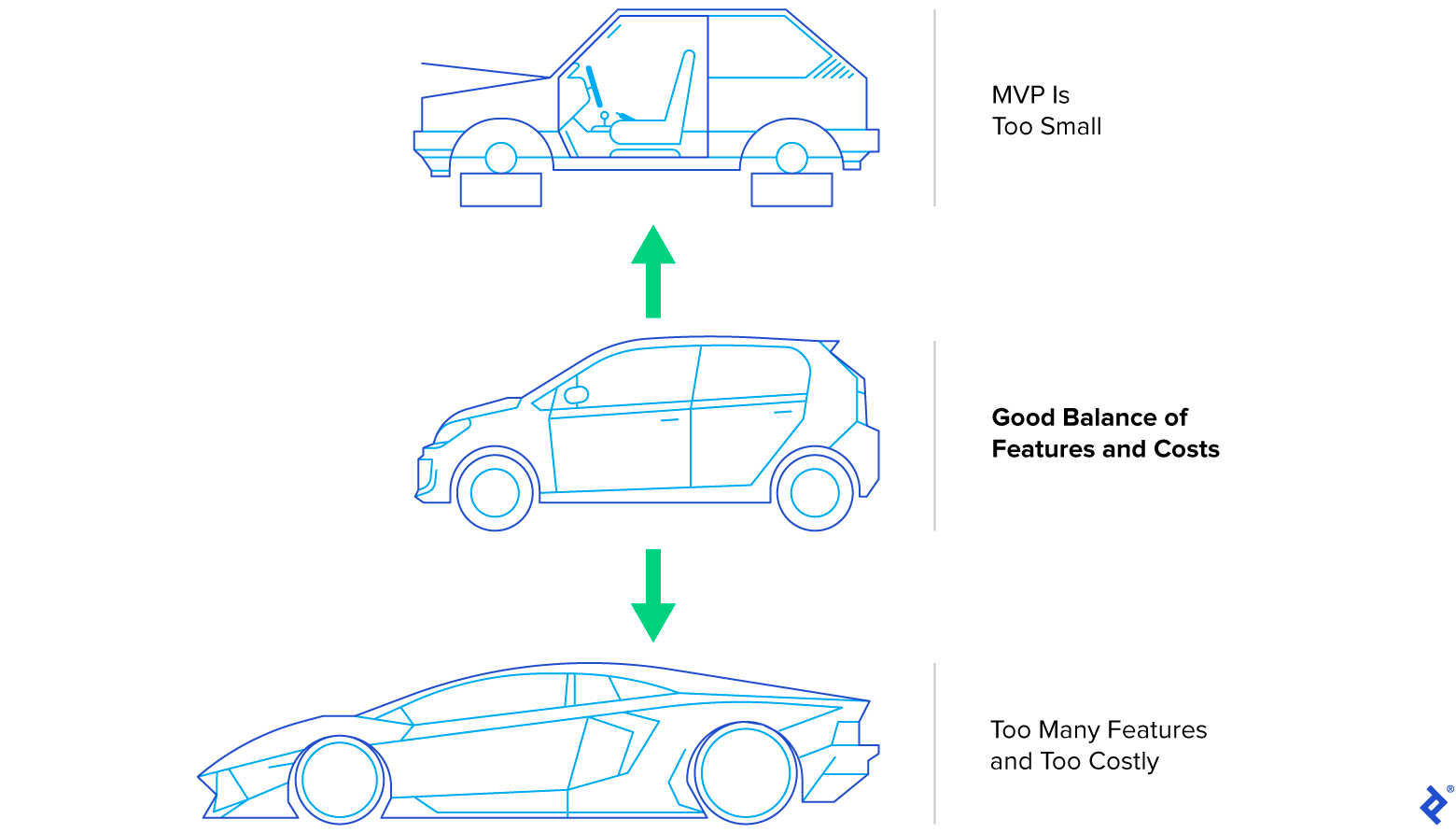

Agile sprints allow rapid version iterations to align more closely with client needs. In many markets, at least one existing provider has established a baseline against which newcomers are compared. For example, when Lyft entered Uber’s space, potential clients had pre-existing expectations and experience with how ride-sharing services work. During market entry, many product managers follow some variation of this scripted approach:

- Launch an MVP with baseline features and pricing parity.

- Acquire beachhead clients.

- Better understand market needs.

- Build a truly differentiated offer and grow market share.

Unfortunately, competition keeps pushing out the step-one finish line, delaying progression to critical steps 2–4. Getting quickly to growth is the desired outcome.

Teams design MVPs at both ends of the feature continuum but less often in the middle. They envision basic and premium tiers and build an initial base version with too few capabilities. Alternatively, they solve for the superset of problems that is too much for 95% of buyers.

These too-little or too-much offers for how to capture market share can’t compete with upstarts tailoring MVP offers to the largest demographic they can credibly serve, powered by sales teams incented to win those clients at all costs. Teams trying to catch up, feature-wise, or overbuilding capabilities will never achieve critical mass. Because it’s counterintuitive to prioritize driving sales volumes when cycles can be used for service experience improvements, many well-intentioned product teams focus on building the best product.

4 Strategies for Bigger vs. Better

Avoid Automating Processes Prematurely

Usual scenario: The business case projects such high sales that service must be fully automated to accommodate expected orders. This includes operational commitments to automate the manual processes in place to support early adopters.

Strategy: Don’t Do It—at least not right away. Products almost always ramp more slowly than pre-launch projections. Prioritizing automation over driving sales volumes is a big mistake. Automation doesn’t sell more widgets, as clients rarely see behind the curtain, but recognizing revenue from selling more widgets is the leverage that accelerates development to scale.

The mantra If you build it, they will come is an exception rather than the norm. Both before and after launch, focus on partnerships, sales compensation, bundling, subscription models, social interactions, and other things that reinforce your value proposition and drive sales and client behavior. Implement five new ways to create sales velocity before adding back-office automation.

Avoid Racing to Feature Parity

Usual scenario: Product Managers treat functional parity as the absolute minimum to be competitive in the market.

Strategy: Winners win because they provide more value, not more features. The problem is that these additions are often features that can be added quickly but don’t sway buyer decisions. Zealous product teams have made a difference by adding capabilities unavailable from any competitor. Less can be more with the right value proposition.

Consider two analytics companies creating performance dashboards from the same data processed through their respective reporting engines. One product team markets a general visualization package vying for market share in a crowded field of business analytics providers. The other is a P&L plan adapting similar underlying technology to create a security compliance verification product addressing an underserved market need.

Engage Other Departments

Usual scenario: Product managers are active participants in the development process, but they can’t do everything. Teams from marketing, legal, regulatory, operations, and sales need to be accountable for their contributions to the product’s success.

Strategy: People do what’s best for them. Product managers are evaluated on financial results. Other teams have different objectives. A marketing team might be incented to deliver content or social media campaigns aligned with a launch timeline. An operations team might be driven to find ways to support more clients with fewer resources. Legal teams might recommend risk avoidance policies that protect the company’s reputation but prevent impactful sales.

Business leaders must tirelessly evangelize the program’s value to the extended team in order to gain the alignment and collaboration necessary to deliver the required results. They must invest significant time with internal leaders understanding roadblocks while demonstrating the willingness to escalate budget approvals, develop risk mitigation strategies, reassign underutilized resources, and generally overcome the objections that underpin the typical excuses for non-performance. Product managers can’t do everything, but ultimately, product managers are responsible for ensuring program goals are realized—even as individual teams push to meet their own siloed but potentially conflicting objectives.

Avoid Free Trials

Usual scenario: If business users experience this incredible product, most will convert to paying subscribers. Alternatively, if users get familiar with a limited version, they will eventually subscribe to the full-feature offering when available.

Strategy: Free trials allow friendly clients to validate prototypes but are rarely useful in creating market leaders. More often, trials consume development and operational resources with no clear path to revenue. This is primarily because business clients have different procurement and risk assessment processes, which make adopting trial conditions difficult. In the worst case, free trials broadcast to your competitors that your offering is not production-ready, a fact that they will actively use to sell against you.

A better option is to craft a for-fee offer that uniquely solves a problem for a limited number of well-defined clients, coupled with aggressive marketing and discounting, if needed, to win that market subset. With this approach, the client has agreed to your contractual terms (which often doesn’t happen in a trial), the company is positioned as a thought leader, and it can leverage these early wins as references for the next round of opportunities.

It is better to sell clients a service with a 100% discount for the first three months than to have those same prospects accept a free 90-day trial.

While semantically both options seem similar, there are tremendous benefits to the former—a “real” client can be reported, and the conversion potential to a paid subscriber has increased by 10x or more, simply because they have signed the agreement.

Focus on Bigger - Better Will Follow

“What is the importance of market share?” is a hard question to answer. Ultimately, to build momentum for future investment and expansion, great products need clients to experience them. Client acquisition is hard work that doesn’t happen by magic or accident. The more effort that is put into making the product bigger by finding ways to get sales to sell the product faster to more people, the greater the chances of getting resources to make the offer better in ways that clients truly care about.

Understanding the basics

What is a product feature matrix?

A product feature matrix shows which client needs are met by particular features of a given product. Analyzing the product feature matrix can reveal unmet needs and market opportunities.

How can a product increase market share?

A product can increase market share by creating value propositions that satisfy unmet client needs. However, even the perfect product needs a lot of investment in terms of the sales process to successfully reach clients.

How do you find the market share of a product?

You can find the market share of a product by dividing the total current sales by total market size, which can be figured out from public statistics or rough calculations.

What is an example of a market share?

An example of a market share could be a 15-20% Apple market share in the smartphone market. It means that around 15-20% of people worldwide use iPhones.

What is the optimal market share?

Optimal market share would be considered such where increasing or decreasing the market share would result in lower long-term revenues. Only the biggest companies in the world face this challenge, while most of their competitors only focus on increasing the market share.

Eric Nowak

Manassas, VA, United States

Member since October 29, 2019

About the author

A former software engineer and analytics expert, Eric built a $1.2 billion network and security business from scratch.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT