The Ultimate Introduction to Agile Project Management

Simply calling something agile isn’t particularly helpful. The word, even in a software context, means different things to different people or organizations. There are many facets, definitions, implementations, and interpretations.

This introduction to Agile project management discusses the behaviors, frameworks, techniques, and concepts supporting Agile approaches to software development.

Simply calling something agile isn’t particularly helpful. The word, even in a software context, means different things to different people or organizations. There are many facets, definitions, implementations, and interpretations.

This introduction to Agile project management discusses the behaviors, frameworks, techniques, and concepts supporting Agile approaches to software development.

The Brief

You’re in charge of delivering your company’s latest and greatest initiative that’s going to change the face of “Widgets International” forever. It’s a software project that’ll engage and enthrall your customers, make your colleagues’ lives easier, and make the company millions in revenue. There’s a great deal of anticipation, fervor, excitement, and expectation. You need to get it done as quickly as possible so your business can start to reap the benefits. The future success of the company depends on you. All eyes are on you. You cannot fail.

At first, you’re thinking to yourself, “Awesome, I’m up for the challenge. Let’s get this thing done!” You pause for a moment, step back, and think to yourself “Okay, so how do we do this?” You start to talk to your colleagues and peers. You spend time searching for best practice software development and project management techniques, but the options and approaches are countless. There are acronyms and methodologies aplenty. Notable ones rise to the top. Doubt creeps in. Which one should we use? How can I guarantee success? What if I make the wrong decisions?

When it comes to managing software projects, there’s a heady mix of options supported by myriad opinions. Voices from the corners of the room whisper, “Try doing it this way”; others shout, “This is the only way to do it”; and the rest just whimper, “Don’t manage it at all, just get on with it.” In reality, all those voices speak some truth. When starting an Agile project, in particular, what’s important is working out what’s right for your needs, your team, your business, and your customers.

Setting the Scene

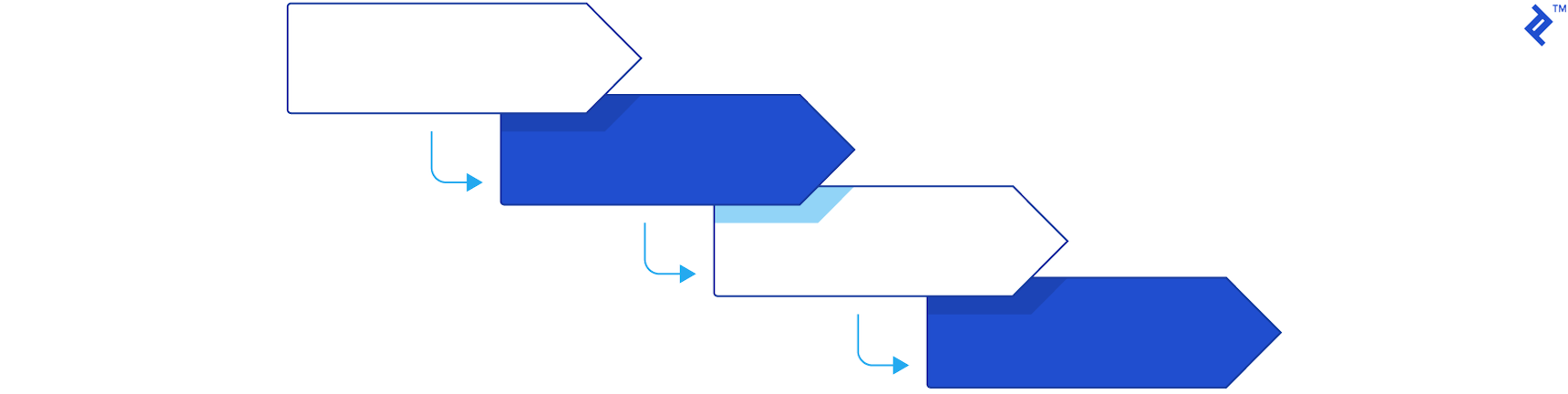

There was a time when software project management sat squarely in one of three camps. There were the heavy frameworks that let you make decisions on how you execute and deliver while offering a structure to maintain control and governance. There were prescriptive sequential methodologies like waterfall that forced you to plan lengthy projects, understand and commit to all your requirements, design and sign off complex systems, write lots of code, and then test (all before your customer gets to see it for the first time). And finally, the less prescriptive but iterative software development life cycles (SDLC) that encourage rapid prototyping or larger systems to be designed, built, and delivered in incremental steps, each building on top of the other.

Agile software development and Agile project management were born out of the inadequacies of the waterfall and the benefits of the iterative approaches to software delivery. They can trace their roots to the 1950s, thought leadership in the 70s, maturity in the 90s, and adoption through the 00s. In 2001, a group of practitioners and experts created the Agile Manifesto, aimed at defining 4 values and 12 guiding principles that seek to embody the spirit of Agile software development and to encourage its evolution. And it has definitely evolved.

Now, simply calling something Agile isn’t particularly helpful. The word, even in a software context, means different things to different people or organizations. There are Agile project management definitions, implementations, and interpretations. Each body that embraces Agile tends to try to give it its own definition.

Suffice it to say that Agile project management and Agile software development are a group of related behaviors, scaled frameworks, techniques, and concepts that fundamentally favor the delivery of the right working software as early and as frequently as realistically possible.

I mentioned earlier that Agile, as applied to software development or project management, can be different things. In a nutshell, Agile software development takes care of developing great software in a business as usual (BAU) or project context. Agile project management, on the other hand, takes care of the governance and control required to deliver complex projects including but not limited to software.

There are many Agile software development methods available, such as Scrum, Kanban, XP, and Lean Software Development. But just as the game of rugby is about more than the scrum, so is Agile. In isolation, these Agile paradigms do not address the full lifecycle of project management required in complex projects such as governance, resourcing, financial, explicit risk management, and many other important project management concepts. For these, you might want to consider PMI Agile or PRINCE2 Agile—think of it as “Governed Agility.”

Why Do We Need to Be Agile?

Long ago, we roamed the land to gather food and shelter to survive. They were simple needs, but pretty agile. Some time later, countries and economies grew and prospered on the back of the Industrial Revolution. This was the birth of management and control and the loss of agility. Now we’re in the Information Age or Revolution, where businesses employ knowledge workers. Knowledge workers are you, your partners, and your colleagues and peers, who endeavor to create great solutions to customer, business, social, economic, and world problems. Knowledge workers apply analysis, knowledge, reasoning, understanding, expertise, and skills to often loosely-defined and changing needs. These businesses and workers need methods and techniques that cannot be met by old Industrial Age processes and procedures. Agile supports interactions.

Virtually no software project can confidently set out at the beginning and know all that it needs in order to deliver valuable working software without change. Change presents both opportunities and risks to the success of a project. Unmanaged opportunities can mean the difference between a great company and an awesome company. Unmanaged risk spells disaster and ruin. Agile manages change.

Adopting Agile allows you to be responsive to changing or new requirements. It empowers development teams to be the experts and make decisions supported by an engaged, trusting, and informed business. It enables you to deliver to customers what they really want. Ultimately, it puts you and your organization in control of delivering high-quality, valuable software that delivers on customer need and expectations while extracting a return on your investment dollars as early as possible. Agile creates value.

There is a cost to adopting Agile. It doesn’t come for free. Transforming to an Agile approach for software delivery can be a hard path to follow. However, if you internalize the Agile philosophy, tread carefully, engage the right team with the right attitude, break things down, make it achievable and realistic, and respond to feedback, you will reap rewards. Agile emphasizes collaboration.

The following lists some benefits you can expect:

- Speed to market

- Earlier revenue generation

- Regular delivery of real value

- Protection for your investment

- Data, data, data

- Better product quality

- Manageable expectations

- Greater customer satisfaction

- Higher performing teams

- Improved visibility on progress

- Predictability, transparency, and confidence

- Manageable risk

Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.

Winston Churchill may never have actually said this, but I think it’s a pretty good summation of Agile. We know Agile is the best foot forward for most projects. It encourages you to strive for success, but we always iterate and keep building on it. Agile will encourage you to fail, but fail early and move on. Having the courage to continue and to build the right solution based on insight informed by your customer is what brings the reward.

The thing to keep in mind is you can tailor Agile to your needs. Use the method and governance that is right for your business. Wherever you start, be true to the content, context, and spirit of the method you use—keep it vanilla. If you’re just starting out, learn. If you’ve been doing it for a while, understand. If you’re becoming awesome, apply. Finally, if your business and your projects are complex and interdependent, govern. Over time, you and your teams will figure out what works best for your business.

Feasibility

So now you’re thinking, “Okay, I get it. How do I start? Where do I start?” Well, with all good things, we start at the beginning. And with Agile, it’s by asking yourself “What business value do I want to deliver?” After all, that’s why we undertake projects, to generate business value. In order to establish if the project is worth undertaking to derive the business value, you need to understand whether it is feasible.

Vision

Is your project projected to increase revenue, enter a new market, acquire more customers, improve customer perception, or make life easier for a given problem you’ve identified? With this in mind, you can state your “vision.”

- Your vision may come from different sources—your own bold startup to fix a common problem, business management strategy, your CEO’s pet project, a specific product team, or even your customer’s needs.

- Try to take a step back from your own shoes and “see” what the future looks like with your new product or service in the hands of your customers.

- Engage your stakeholders—the CEO, product guy, and customers. Workshop it, don’t attempt this in isolation. Challenge assumptions and validate arguments.

- Write it down, keep it short. Focus on the business value.

- Refine it until you all agree the vision resonates with everybody and meets a common interpretation that states where you’re heading.

- Your vision, if valid, rarely changes. How you get there most certainly will.

People don’t buy what you do, or how you do it. They buy the “why” you do it. This is what creates the emotional connection between your business and your customers. The vision will help illustrate this.

Is It Feasible?

Feasibility comes in at least a couple of shades. Typically, you’ll want to understand if your vision of a brighter future for your business and customers is both technically feasible and that it’s feasible for your business to make it happen.

- If your vision is to make travel to anywhere across the world in under an hour, you may have a problem with the technical feasibility. Since science, physics, and technology haven’t quite caught up with that dream yet, your technical solution may not be viable in anything other than theory. In addition, if your solution was new, this would go well beyond the idea of a minimum viable product (MVP).

-

To test the technical feasibility of your product, consider either exploring it further in a Discovery prototype project or by running a spike in the early stages of the project. You’ll know which method to use by thinking about the scale or complexity of the solution you have in mind.

“Some of the best knowledge my teams have gained in understanding technical feasibility have come from performing a spike. And often, it’s the simplest solution that wins out!”

- The second shade of feasibility to consider is whether you, your team, or your business has the skills and motivation to make it work. Using an example, if you’re great at baking cakes at home for your kids birthday, that’s sweet. But if you want to turn this into a business selling the finest cakes to the world, you need to understand if you can make it scale, handle the business as well as the production, manage distribution and fulfillment, and take care of customer service.

- This type of vision might be achievable in the long run. But for now, possibly not. So scale it back, think small, take a small chunk that looks realistic and concentrate on delivering the best smaller aspiration you can. If that manages to engage and delight your customers, get them coming back for more and telling their friends, then scale it up from there using your customer feedback as your guide and compass.

- Also, you need to know if your project is feasible in terms of budget and timeframe. Can your business afford to deliver this project ? Is the timeframe achievable? Time and money are two of the three constraints in an Agile project that are fixed. We aim to deliver within a given fixed time and within a given fixed budget.

- The quality of a product refers to the end product that your customers use and the engineering practices your team uses to deliver great, robust, and reliable software. Quality is also something we don’t short change. Quality criteria, on the other hand, can change. If you’re not setting out to build a Ferrari, the product may not have a high quality perception. If you’re not building space rockets, then the tolerances attained in production terms may be much higher. Set the appropriate tone and expectation early on.

So now you’ve confirmed your dream is more than chocolate fancy, set about testing your assumptions and proving to people that this endeavor is worth investing in.

Justification

Now, depending on your circumstances, justification will come in different forms. But essentially, you want to prove that this project will satisfy customer success criteria, has a chance of success, will deliver value, and is affordable.

- State your assumptions based on your customer need, then validate them. The Lean Startup gives great guidance on identifying and proving that your product is needed by your customers and will create value.

-

Write, test, and validate your business plan. Now this looks nothing like the ones your bank or your business and finance major told you to produce. Don’t use them—they will be out of date before the ink is dry. Instead, check out the Business Model Canvas. This is essentially a short-form business plan that keeps your focus on your value proposition, your customers, revenue, and costs. Use it to validate if you have a business that will work.

“I ignored this advice once and spent a long time writing a lengthy traditional 50 page business plan. It got me nowhere. All the assumptions I had made were unfounded, and all the projections I made couldn’t be validated. It was a painful and expensive experience that taught me to never do it again.”

- If you’re in a mature business with portfolios of projects being delivered in a complex environment, then financial modeling may be necessary. If you must, do this only after you’ve proven the above.

- Once you’ve built your MVP, there may be a case for creating a more traditional business plan—for example, if you have to go for funding or selection within your company’s portfolio of competing projects and resources. But this will be a business plan based on and informed by the tools used above. It will be lighter too.

- In any case, use these tools as living, breathing artifacts. Use them as your guide and bellwether. They are never static. Refer to them and revise them as your project or business evolves.

Once you have your justification and all your stakeholders are on board, you’ll be on fire.

The feasibility phase is typically performed once in the life of your project. You may find you revisit the vision and feasibility of the project, especially if your data, customers, market, or business indicate so. At the very least, they will be your guiding lights throughout.

Initiation

Awesome. The decision has been made, the project has the green light and you’re ready to build. Well, nearly. I know you’re thinking, “C’mon already, really? If we don’t do this now we never will. Let’s get this show on the road!” But consider this—Agile is nothing if not about delivering value early and often while delighting your customers along the way. Taking some time to figure out the best way to deliver your project is the best laid foundation for success.

The Team

In sports, by thinking about your favorite team game, you’ll be able to recognize key roles that enable the team to perform as they do. Traditionally, you’ll find a manager, a captain, and the rest of the squad. Outside of that, you’ll find coaches, physios, nutritionists, and an assortment of supporting staff. But if we look at the game of rugby, there’s a team within a team: the players that make up the scrum. This pack is made up of designated players whose job it is to win the ball back and continue play. When a scrum is in play, the players from each side then work, with no leader, as a single unit as collaboratively, communicatively, and efficiently as possible to get the ball back in possession. It is the game of rugby that inspired Jeff Sutherland to name his software development methodology “Scrum.”

- Scrum is not the only software development method in the Agile playbook. But it is the one that best describes the Agile concept and behaviors of working as a team, motivating individuals, creating trusting relationships, self-organization, servant-leadership, communication, transparency, and collaboration.

- Your team will be formed largely by the circumstances you find yourself in. You may have developers available to you. Some, none, or all of them may be familiar with Agile to varying degrees. You may want to hire a new team or partner with a third party.

- Other roles will be required too, but we’ll discuss those later.

- It has been said that if your form your development team, then you’ve chosen your technology. Depending on where you bring your team together from, they’ll come with specific skillsets. So, think carefully how you form your development team and whether you need to perform a technical evaluation before you get to this point in your journey.

- This brings us to cross-functional teams. Teams work best when they work together, when individuals pitch in to get the job done regardless of their title. Try to build a team that is self sufficient and individuals that take on more than one role.

- Build an environment, culture, and relationship center—a place where the team can deliver, unencumbered by constraints or restrictions. Give the team the tools, people, resources, and space to be effective and performant.

- Keep team sizes to no more than seven or eight. If you have a need for many more developers, split the team into multiple new teams. Each team might then be responsible for a given functional area. If you you have multiple teams in multiple locations, consider holding a Scrum of Scrums. And where these are numerous in complex environments, use Agile project management.

- Ensure that the team, business, stakeholders, and even customers have access to one another. Ensure they communicate and collaborate, and remove anything that gets in the way of progress. Daily communication is the best cure for project ailments. When people speak, they get stuff done.

There are many ways a team can be put together to deliver software.

Project Brief

In the feasibility step, you figured out the “why” of your project and either built your confidence to forge ahead with your startup or got backing to proceed. The project brief is the living document that brings together the “why” with the “what” and “when” and “who.” It’s “living” because, as you progress, your knowledge, understanding, and path may change. To leave this document once written and never to return to it just consigns your thoughts to a point in time. In an Agile world, your point-in-time reference may change weekly or even daily early on, so it’s important to keep this fresh.

- A great tool for encapsulating and maintaining your project brief is something that Jonathan Rasmusson calls the “inception deck” in his book The Agile Samurai. Here, you’ll find great advice on ensuring that everybody that is interested in, affected by, or involved with your project is on the same page.

- The greatest enemy to delivering projects is in having an unclear, inconsistent, or just plain different understanding of what the project is and what “requirements” are to be satisfied. If even one important stakeholder has a different understanding or view of what you’re doing, the consequences can be substantial.

- A good project brief communicates:

- A common and agreed-upon expectation between stakeholders and team members.

- An understanding of the project, with the same understanding across all parties.

- The goal, vision, objective, scope, and project context.

- You’ll have a lot of good information for the brief gathered from feasibility. The project brief will help you define and find the answers to searching questions. It will bring together stakeholders, your raison d’etre, high-level scope, risks, target solution, budget, timeline, expectations, and priorities.

A colleague stopped me in a corridor once and asked me where he could get the project brief for the project. I quipped ‘We don’t need a brief, we’re Agile’. He looked confused, as if he was questioning my sanity or authority. He was right to do so.

Before you proceed, ensure you’ve got everybody on the same page, workshop it, ask the difficult questions, and nail it up somewhere where people can stop, read it, comment on it, and help revise it.

Culture and Ways of Working

You know the way your business works and its culture, the way it likes to get stuff done. Agile, by its very nature, may challenge some of these ways of working that your business has cultivated over the years. Don’t expect Agile to be implemented and for everybody to lovingly adopt it from the outset. Some people may find it confusing and view it only with dread and fear. Some people may openly refuse to engage in it. These are challenges and perceptions you must overcome. But in your early days, don’t go around waving the Agile stick beating anyone that won’t listen with it. That won’t build trust, adoption, or engagement.

I was a fan of waving big proverbial sticks once, and it earned me a lot of negative press. I turned it around, but not before suffering considerable pain first.

As you set out on your path of adoption, tread carefully, respectfully, and with empathy. If you’re in a creaking old traditional business, perhaps it won’t be the best approach to get the whole business aligned. Start small and incrementally earn respect and recognition. Start with your team only. Once you start delivering quicker software with better quality than ever before, people will start to notice and will want to come play your game. When they do, offer them the ball, take them out for a coffee, and ease them into your new world. Help them.

With your team, now that they know what the project is about and your plans for Agile adoption are agreed upon, let the team decide how they wish to behave and operate as a team.

- Guide your team to identify the Agile concepts, techniques, behaviors, and frameworks that you feel fits your collective needs.

- Take requests from your team members as to what requirements they have to help them perform as best they can. Some of these requests, you’ll be able to resolve immediately. Others, you may need to get budget or outside help. Do what you can to make it happen.

- These are your first steps to becoming a true servant-leader.

- Consider organizing some appropriate training in the concepts and techniques your team is choosing to adopt. This is the best way to ensure all of your team members, even stakeholders, are on the same page and get the same message. Work with a supplier organization that can tailor their offering to your needs.

- Be prudent. Nobody will be an Agile ninja after a few days in a workshop learning how to become Agile. Your path will be long. The word “become” is quite defining. Only when you truly embrace Agile will you see its value. It should excite you. If it excites you, then go excite others too.

- Now that your team has agreed upon the concepts and techniques, had their wishes fulfilled, and are in Agile training, turn your team’s attention to themselves and what they expect from you, the business, and one another.

- Define some ways of working (WoW) within and by the team helps build trust, relationship, and expectations. The WoW is no War and Peace. It should be short and to the point, between seven and ten bullet pointed sentences. These sentences state clearly how people behave, communicate, collaborate, support, deliver, and perform together. It should also state what the team expects from the business.

- Agile is as much a mindset as it is guiding principles and concepts. It helps you develop in the way you behave, think, negotiate, interact, communicate, perform, and improve. It relies on motivated individuals supporting each other to reach a common aim, together as one. There is an African proverb:

By now, your team should be super excited, energized, and motivated. Now, engage them further with your backlog of user stories.

Backlog

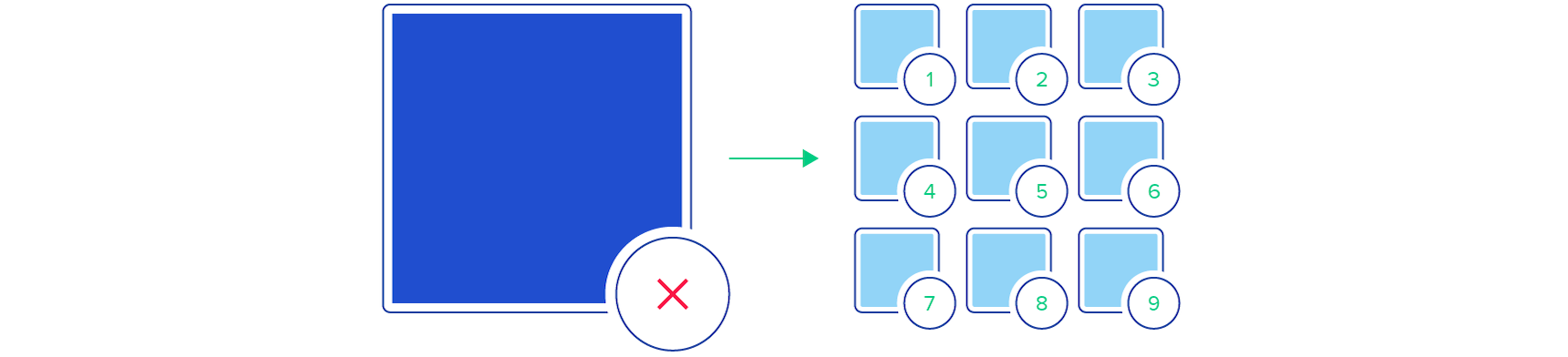

Have no doubt in your mind that there’s uncertainty involved in your project. You can’t possibly know exactly what it will take to build the right product for your customers so early in its life. You cannot gaze wistfully into a crystal ball and predict the future.

The “backlog” or “product backlog” is where your requirements live. Agile favors the writing of short, pithy statements that capture the essence of a “requirement.” The backlog is simply a long list of entries, each entry defining a single, discrete “requirement” as a user story. And from now on, we’ll be using the word user story, and not “requirement.” You’re probably asking “why?” That’s a good question. For what seems like forever, stating the features or facets needed in a software project by a customer has always been referred to as a requirement. That word has an interpretation that has no value in Agile. The Oxford dictionary defines it as:

A thing that is needed or wanted. Or, A thing that is compulsory; a necessary condition.

And unfortunately, if we set out defining what our solution should be, stating that things are “compulsory,” we will end up in trouble. It’s too easy to say that all these user stories are compulsory. If we take that view, we run the risk of running over schedule and over budget in the attempt to deliver all of a given scope. It’s not a problem to say that, for this product these stories are needed for the solution to be viable, we just want to avoid the interpretation of that particular word.

- Always write stories from the perspective of a persona. A persona represents a user or stakeholder of the solution. It’s a good idea to develop these persona before you start a backlog.

- At this stage, only write short, simple statements that basically suggest a reminder to have a deeper conversation about the user story when the time is right.

- Real people think in terms of tasks that they need to get done to achieve a goal. Write your stories from the persona perspective and in terms of what they need to get done.

- You don’t need to write the full backlog—just write as much as you can imagine your customers will need for your product to be viable.

- You’ll discover later on through the life of the product that user stories will change, become more or less important, or can be deleted completely. Releasing often, getting feedback, and assessing what’s a priority will inform this behavior.

- Don’t write stories in isolation. Engage your team, stakeholders, even your customers. Stories can be updated at any time in the life of a project but should avoid being changed once development work has started on them.

- Some of your stories may be considered “epics.” These are large stories that cover a lot, and will be broken down closer to the time of delivery into smaller stories.

- Consider using the INVEST model, a checklist for validating the quality of a good user story.

- Anybody can add a story to the backlog. It should be placed at the bottom, or in a specially created “parking lot.” This added story serves as a prompt to discuss with the team and the business. If the business and team support it, it can then be estimated and prioritized

- You may also consider those parts of the system that are most risky. If you have a user story or feature that is complex, new, or technically unknown, prioritize these to the top of your backlog. This way, you won’t be attempting to deliver the challenging and critical parts of your product just weeks before your first release.

Once you have a backlog that fulfills your needs, you can estimate the stories in it, rank them in order of priority, and build a release plan.

High-level Estimation and Prioritization

High-level estimation is the process of sizing your backlog. How “big” is the project, and what value does it deliver? Prioritization is the process of deciding which stories are most important to you, the viability of the product, and the interests of your customers. We want to deliver the highest value items earliest to deliver the most value to the business, get feedback from the customer, and to not sweat the small stuff. The output will be an ordered backlog that is ranked in priority and sized appropriately.

- Stories at the top are considered most valuable. We want to deliver the most valuable items as early as possible.

- There are many techniques for sizing and estimating, but at this point, you just want to get a good indicative feel of the size of a story.

- Use t-shirt sizes, relative sizing, ideal days, or story points.

- You won’t have all the available information at this point either, and that’s okay. Just run with it.

- Engage your business stakeholders or product manager if you have one, and the team that will be doing the work.

- We want those that will be designing, developing, and testing the work to size it, because the best people to estimate are the experts.

- The team may start to break stories down into smaller parts. If this happens, write stories that are more granular but discrete.

- The team may also start to rank some stories, as naturally some things have to get delivered before others to support the technology or a given user journey.

- Between you and the team, you may also start to find holes in the backlog that need to be filled. Just fill those holes with new stories and estimate and prioritize as appropriate.

- Prioritization is most easily performed using a MoSCoW analysis. MoSCoW is a simple technique that helps you decide which stories are “must haves” for your product to be successful.

- You may do a prioritization pass before estimation begins. However, the sizing of certain elements may also determine a decision on priority and real business value. So play estimation and prioritization off of each other, but don’t squabble over it!

- No two stories can be as important as the other. The story at rank 1 is more important or valuable than the story at rank 2.

- A great way to demonstrate the importance or value of a story is it to add a monetary value to it. If for example, story A is thought to bring in $5000 of extra revenue, and story B might attract $100, then story A is more valuable. Equally, if story C saves the business more than story D, story C is more valuable.

- Once you’ve sized your backlog, you’ll be left with a number. When we come to release planning, that number will help us understand how much can be delivered by our team within a given timeframe.

Remember that you don’t need to know all your user stories up front. Also, remember that it’s not necessary to deliver all of your stories before a customer sees your product. You want to remain Agile—and that means only creating what you need to when you need to, wasting as little as possible, and responding to changes in customer needs and market conditions. A roadmap will help you lay out your product and plan your objectives for the next 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Roadmap and Storymaps

A roadmap is exactly as it sounds, it offers the same as a roadmap of a country. It details the relative position of cities (or in your case, features) to each other and the routes that can be taken to get from city A to city B, or feature X and feature Z. It doesn’t tell you which route you should take, or how you should get there. It doesn’t tell you which mode of transport to use, but it might illustrate options to take the highway or the train.

In a city, there are many roads, buildings, parks, services, and facilities. All features of a city. This is also true of the roadmap for your product. At this level, your roadmap shows major goals or milestones to be achieved. A goal is a logical grouping of themes, features, and user stories rolled up in a consumable view that demonstrates tangible value. The roadmap of a software product shares this view and communicates your intent. It doesn’t necessarily show you how or when features will be delivered; only the relative value of the goals and features to you and your business.

One great way to demonstrate a roadmap is to generate a story map. This tool indicates customer valued prioritization. It lays out the backbone, or essential building blocks of your product. The walking skeleton hangs off the backbone and illustrates the features that make it an MVP. All the other features are what add further value and importance to the system. The story map lays features in relative position to each other and is an awesome visual tool.

It’s worth noting that after carrying out a story mapping exercise, your backlog may need to be refined. This will be apparent where stories have been split into multiple stories, identified as redundant, newly created, or as a higher or lower priority than previously thought. The story map is another artifact that is continually revisited and revised.

The Initiation phase is typically performed once in the life of your project. However, many of the tools and documents you created will be revisited and revised throughout the project.

Release Planning

“At last,” I hear you cry, “finally, some planning.” Well, you have essentially been planning all through the feasibility and initiation stages; we just didn’t call it as such. This is evidence of iterative or adaptive planning—the art of only planning enough to achieve your immediate and most valuable goals. We’ll see later more about adaptive planning, but for now release planning is our focus.

Your release plan may well be determined by external events. Perhaps there is a trade show you want to demonstrate your app at, or your customers will get the most benefit using your app on the run-up to Christmas. These are timeline events that your goals may be aligned with. You would most likely plan to deliver user stories or features that make the most sense to facilitate these events. If there are no external dates that you need to consider, then you can just go with feature prioritization and delivering earliest what makes the most sense and delivers the most value to your customers.

- If you created a story map in initiation, this will help guide your release plan. Use it to identify your MVP, the minimum feature set that will get your product in the hands of your customers, start earning revenue, get feedback, and acquire more customers.

- The story map will help you carve out future releases too. But keep in mind that as you learn, get feedback, inspect, and adapt, future releases may change. So don’t plan in great detail.

- You may have from two to four releases in a 12-month period. Don’t do less, because your first release is your MVP and gets your foot in your door, after which you’ll want to iterate and release more features and bug fixes in a regular cycle. Don’t do more unless you’re performing well and have plenty of Agile techniques and tools in place to manage continuous delivery.

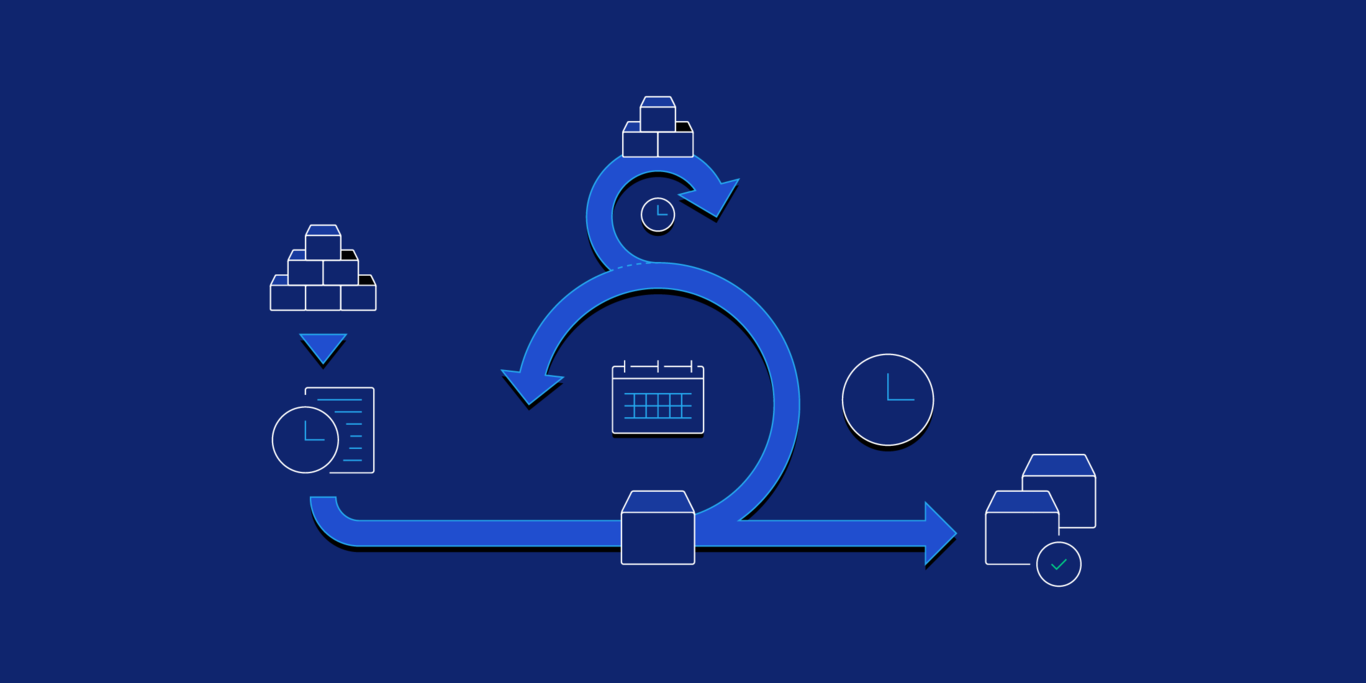

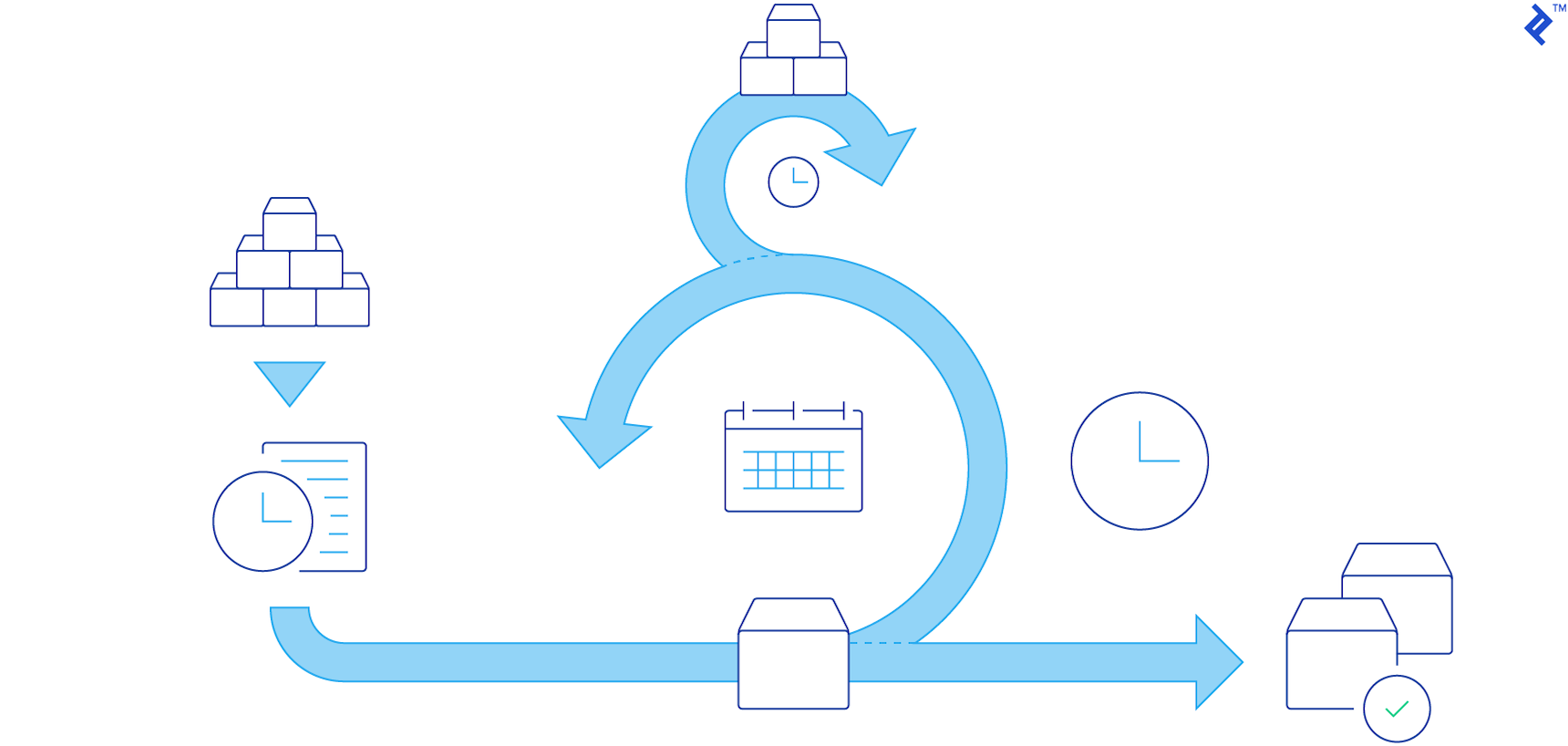

- Each release is a timebox which is broken down into smaller iterations. An iteration is a timebox. The timebox is one of the most important control measures in Agile.

- To size your release:

- Divide your release timebox by two. This will give you how many iterations you have. So if you have a release of 12 weeks, you get six two-week iterations.

- Then remove two iterations—you’ll reserve one for a “sprint 0” iteration and another for a “release” iteration. This leaves you with four development iterations.

- Work with your team and product owner to fill each iteration with stories, starting from the top of the backlog and working down. When the team thinks they’ve filled an iteration with enough stories they can realistically achieve based on their capacity in the two-week timeframe, repeat for the next iteration(s). Use the release plan and story map to guide what goes into each iteration.

- Do not plan the next release yet. You’ll do that as you near the end of the current release.

- Take the user stories from each of your iterations and add up the story sizes. So if your iteration 1 has 25 story points, but iterations 2, 3, and 4 have 10, 45, and 65 points, respectively, you will need to refactor. Target an equal number of story points in each iteration. This becomes your anticipated velocity—the amount of valuable “stuff” completed for each iteration.

- The team may not have worked together before. They are almost certainly working on a new problem or product. They will not perform at their best from day one. For this reason, your velocity may be volatile in the first few sprints. But as the team settles down, it should stabilize. Use this data to refactor your release planning which, in turn, helps you plan your product with a known velocity and confidence.

- If necessary, break stories into smaller chunks and resize.

- Your release plan, especially early in the life of a project and a new team, is only ever a guide. Do not treat it as a commitment or guarantee that all or these exact stories will get delivered as planned. As your team matures, work gets done and trust and confidence builds, so will the accuracy of your plans.

- Never force your team to “commit” to more than they are comfortable with. Trust their judgement and their expertise.

- Future release planning exercises will be simpler, because you’ll take the release size, multiply the number of iterations by your team’s velocity, and fill the release plan with the stories that add up to velocity multiplied by the number of iterations.

Consider this as an example. If you go to a restaurant to eat, you wouldn’t go ahead and order all the items on the menu and expect to eat it all in one sitting. You’d never be able to eat it all, you might not afford the cost, you’ll be sick of food, and the restaurant may close while you’re eating the fifth of 19 courses! You may not leave a happy customer, the restaurant may not find you to be a great customer, and the experience will be bad all around. More likely, if you love the restaurant, it’ll be because you enjoyed a lovely meal there once. You’ll decide to go back and enjoy a different meal. You’ll tell your friends, you’ll go there often. The moral of the story is:

- Plan your releases in small chunks.

- Consider your capacity.

- Don’t take on more than you can realistically achieve.

- Revisit the plan often to see what you can change and improve.

- Plan, execute, inspect, learn, adapt, repeat.

Release planning takes place often in a software project. Each new release requires a release plan. The release plan can also be refactored at any time during a project. Just take care to not overdo it and fall into zombified planning psychosis. At the end of release planning, you’ll want to prepare for the first iteration, which is where we’re happily going next!

Product Iterations

Your team is in place, they’re motivated, you have an engaged business, your initial planning is done—you’re now ready to build your dreams.

We talked earlier about some of the tools, techniques, and concepts that Agile subscribes to. There are many resources already available that do a great job at laying the foundations for delivering an Agile software project. Pick one, keep it vanilla, and grow into your Agile journey. To help shorten the trauma in deciding the right Agile software development methodology to start with, I’d recommend Scrum. And only Scrum. The temptation will be there to use elements of other methodologies. Don’t do it yet. Save that kind of change until you have lived and breathed Scrum for 6 or 12 months. Then, if either you’ve determined it alone does not work for you or you want to mature as a team, steadily introduce new methods, techniques, or frameworks.

I choose Scrum as the recommended approach for new team’s adopting Agile because it has all the basics built in. It’s very popular and has many good-quality communities and resources online, in books, or in the training room. It will serve you well, even for the smallest of teams. The rest of this post is dedicated to discussing some important aspects of software delivery that you, your team, and stakeholders should always keep in mind.

Adaptive Planning

Planning in an Agile project is an ongoing process. We do some initial planning up front, just enough to understand what we know at a given point. Our initial plans will be loosely defined and flawed. And then we iterate our planning, adapting to new information, planning in greater detail just before we enter into delivery, responding to changing scope. This is one way of minimizing waste—only putting effort into planning when we need to.

- The team and the business, or its informed and authorized representative such as a product manager, actively plan together—the team because they are the experts that will deliver and the product manager because the are the experts who can guide the needs of the business.

- Estimates for user stories will be less accurate the further out they are from being developed. For example, epics will attract high-level estimates that will be based on a lot of unknowns. Well-defined and granular user stories that are estimated just before a sprint starts will be much more accurate.

- There are many estimation “scales” you can use. Use the technique that feels most right for your team and the right stage of planning—wide-band delphi, planning poker, ideal time, relative sizing, story points, or t-shirt sizes.

- When sizing a story, one size really does fit all. All stories should be sized using the same technique and encompass all elements such as design, development, testing, and refactoring. When you come to do iteration planning for a sprint, certain tasks can be created which all contribute to the completion of the story.

- Always factor risk, unknowns, outside influences, your team’s capacity, and ever-improving velocity in planning.

- If user stories that were taken into a sprint were not completed, we do not extend the timebox. These unfinished or unstarted items are put back to the top of the backlog and taken into the next sprint.

- Always plan to deliver the least amount required to achieve a given goal. Identify techniques to prune features. Reduce waste and find the real value that can be realistically delivered with your time-constrained resources.

Story Creation

Stories get elaborated upon when you need them. You don’t need full story explanations for features that are six months away from being delivered. Writing them at the beginning may be wasted effort, when that need disappears from scope. Write your stories at most two iterations before they are needed. Reducing that timeframe to one sprint is preferable.

Let’s take your time in sprint 0 to set the scene. In two weeks, you’ll start development. It’s now time to take enough of the stories from the top of the backlog that could potentially get delivered on sprint 1. You might take 10-15% more if you’re unsure on your velocity. These one-liners can now be expanded into truly valuable documents with scenarios, acceptance criteria, and wireframes. If the wireframes haven’t been created yet, now’s the time to do so. You might find as you review these candidate stories that they need to be broken down. Perhaps they were epics that couldn’t possibly be completed in a sprint. If you break stories down, re-estimate them with the team.

A good story follows the following rules: - Written in a common format, e.g., AS A <persona> I WANT <to do some task> SO THAT <achieve some result>. - Includes acceptance criteria that the story must meet to be considered acceptable to the business for sign-off. - Uses language that the business and your customers understand. - Follows the INVEST model. - Includes all supporting documents to inform the developer, designer, and tester: wireframes, technical design overview, other assets. - Meets your standard “definition of done” criteria.

Sprinting

Whether you call it a sprint, an iteration, or a timebox, each incremental delivery of your Agile project is time-constrained. The timebox doesn’t shorten and it doesn’t lengthen. Focus on two-week iterations at the beginning. You might find that 1, 3 or 4 weeks suits your business model better. Once you choose a length, don’t change it. You want to maintain a regular cadence, or a sustainable pace. This means the team and business focus on delivering regular software without mad-dash overtime being employed to get the job done and releasing potentially shippable increments every two weeks.

- Working in small increments has a huge benefit. It means you’re only focusing on the immediate future of delivery and, with new input, feedback, and learning, you can respond to change within a short iterative cycle.

- At the beginning of a release, perform a sprint 0. This lets the team, the business, and your project release get geared up and sets the mindset for successful delivery. Draw out the base technical framework and architecture that will support the foundation for the release. Set up environments, accounts, and tools. Perform spikes to understand difficult or unknown problems. Elaborate your user stories in readiness for sprint 1. Sprint 0 is about getting prepared.

- During a release, keep refining the backlog. As you understand more or learn something new, your priorities may change, new requirements may unfold, and what you previously thought was a great feature may get removed entirely.

- Don’t start work that has no chance of completing within a sprint. If it can’t, break it down into smaller chunks. And don’t start new work when previously started work has not been completed. You create no value by starting lots of things that can’t be considered complete. Further, avoid context-switching. This is the activity of starting one task, getting disturbed, starting another and, at its most problematic, not completing either.

- Limit the amount of work that is in progress by the team at any one time. For example, if you have three developers and one tester, you may put a WIP limit on the developers and on the tester.

- Never add more work to a sprint after it has been planned. Never stop a sprint partway through. The exceptions to this are:

- If you performed faster than expected, consider taking the next story from the top of the backlog, as long as it is suitably prepared.

- If the sprint is performing so badly that it will not complete. This usually only happens where there has been a catastrophe of some description.

- If the sprint objective can no longer be supported due to immediate changing needs of the business.

- If you do cancel a sprint, do it gracefully, take time to refocus, and start a new sprint as you would any other.

- Toward the end of a release, consider a final release sprint. No new features are written, some bugs can be cleaned up, and preparations can be made to actually release a new version of your product to your customers. That’s not to say you can’t make incremental customer releases in the meantime—it’s just that this is a controlled, measured, and sustainable release mechanism.

- At the end of a release, you might consider a one-week sprint. In this sprint, you might work with the team to breakdown some new ideas or figure out some new technology. These are great tools that benefit the business, and it gives the team some briefing space to think and be creative. It’s not for goofing off and will still create value. Equally, everyone needs a break. Taking a vacation at this time helps keep your cadence and velocity in good shape when you’re mid-release.

Defining Done

Defining what “done” really means is very important. There are many versions of “done” within the life of your project—what it means to be “done” with a story, release, or whole project. It all boils down to what you, your team, and business will consider as complete to the right level of quality to satisfy readiness to ship.

For your team, the definition of a “done” story will be something like all code complete, peer reviewed, meets the defined acceptance criteria, unit tested, UAT’ed, and pushed to your code repository. To enable the passing of a story from designer to developer to tester, definitions of “done” will have to be accepted by the next person in the chain. Your product owner will have expectations as to what this means to them in order to release the product increment to your customers. In any case, everybody must be aware of what “done” means and be a responsible party in ensuring its meaning is met. Define your definition of “done,” communicate it, agree upon it and, evolve it. Done done.

Continuous Measurement

If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. The same goes for improvements. The need to gather empirical data in an Agile project is almost as vital as having blood course through your veins! How do you know what needs managing, correcting, or improving if there’s no data? Well, simply put, you’ll be relying on gut feel and unsubstantiated guesswork, which falls apart pretty quickly under scrutiny. And depending on who’s doing the scrutinizing, this can be a rather uncomfortable place to be. So from the outset of your project, ensure you know how you are going to demonstrate progress and by what measures others are going to view your success.

Fortunately, Agile comes loaded with useful tools and techniques. The first thing to do is go back to the Agile Manifesto, type the following words into your favorite word processor, blow them up to 96pt, print, and apply to the wall for all to see :

Your greatest demonstrable power in delivering software is to show it to people working, doing what it’s supposed to do. Not only will this make your customers happy, it will earn your team great respect and grease the wheels for greater adoption through the business.

Here are some other tools:

- The daily standup: There are a few variations of this ceremony, but the essence is to have all team members talk to each other face to face: Keep it short, keep it focused, and keep it light. If anything needs discussion at great length, park it for a longer conversation between those needed after the standup. If impediments are raised, write them up like a story, add them to your backlog, and get them addressed asap. Anything that is impeding your team slows their progress and will be demonstrable in reduced velocity and software that does not meet expectations.

- Velocity: Is a historical tool. It’s a little like those financial warnings you get that says past performance is no guarantee of future performance. But in Agile’s case, we do hope to achieve a team velocity that is largely smooth. It’s velocity that allows us to project future performance and confidence in our plans. There may be influences outside your control which might lower the number of story points output for a given sprint. If this happens, you’ll probably be able to recover. Never use velocity as a stick to beat your team with; it will win you no favors. One thing for sure is that velocity will be erratic for the first 2–4 sprints. Somewhere in that timeframe, though, you should start to see consistency and stability. If your velocity is wavering from one extreme to another, you’ve got a problem which you’ll need to fix with your team.

- The burndown chart: Now this measure of progress is a thorny one. For that reason, I haven’t given a link to go find out more—you’ll have to do your own research and agree as a team and business which works for you. The reason it’s thorny? Well, not one resource out there tells the same story! One thing agreed upon is that it will show, within a sprint or a release, how you’re performing against your timebox. If maintained daily, it will show if you’re on track or deviating. Some teams use it to represent how much value is left to be created, more often than not, others use it to show how much work is left to be completed. The former is a celebration of success and value generation, the latter is less inspiring and motivating.

- The burnup chart: If you must show work completion rates, use the burndown chart for that. But using the burnup chart allows you to show how much value has been created and how much more value you’re planning to create by the end of the sprint. A much more motivating tool for a team to both demonstrate to the business what has been done (or little if things aren’t going so well…) and what they still have their sights set on. In any case, use the charts to spot where progress is not tracking as expected and look for patterns or deviations and get on top of them to fix the underlying problem as soon as possible. Update them daily for sprints and once at the end of a sprint for release version charts.

- Task boards: These are great visual radiators for demonstrating value being created. When updated daily, or at any point in the day, they immediately show progress being made. If combined with Kanban, they’re also great tools for visualizing flow and blockages in the system. If you can see that lots of development has been completed, but testing is not as productive, you can see the problem happening and respond appropriately and swiftly.

Other tools to consider are Agile earned value, cycle time, and cumulative flow diagrams (CFD’s).

Keep these measures, charts, and other tools visible, preferably loud and proud on a wall for all to see. The team, stakeholders, and other interested parties can immediately see the status of a project. It’s transparent and serves as a valuable communication tool. If you can’t put these artifacts on a wall, use tools that are sharable and collaborative and make sure those that want access have it.

Continuous Improvement

Throughout your Agile life, seek to identify and learn where improvements can be made. Lessons are not captured and learned at the end of a project. It’s like passing your driving test and tentatively taking your first drive without an instructor. You’ll know what works and what you’re supposed to do, but over time you’ll tailor your driving skill and capabilities, learning new techniques. You’ll even pick up bad habits. Look for them, understand them, and find ways to improve.

There are many opportunities for identifying what does not work and applying remedies. The built-in approach to this in Agile is the retrospective. This is the primary tool for reflection and adjustment. At the end of every sprint, take time with the team to improve how work gets done, how quality is delivered, how efficiency can be maximized, how waste can be minimized and how capacity is increased. When you identify measures for improvement, don’t be tempted to fix all your problems right away. Identify the ones that will have most impact and can be implemented in the next sprint. Measure and observe. If it had the desired impact, lock it up, write it up into your ways of working and definitions of done. If it doesn’t work, think again. Any lessons learned that don’t get put into the upcoming sprint can be parked and prioritized for attention in the next sprint.

Tailor the process. Remove anything that does not work. Remove impediments. Your maturity as an Agile team will know no bounds if you let it.

Beyond Agile Project Management

It’s important to know what happens after the project is delivered. Support and maintenance are key to ensuring that, once the project is in customers’ hands, it remains performant; customer feedback can be factored into future releases; and customer issues are dealt with appropriately. A project is a unique, time-constrained endeavor. The product it delivers has a life after the project team has been disbanded. Ensure that you are capable of supporting the product once it is live.

Agile projects co-exist with more traditional approaches. Balancing the requirements for budgetary control and stakeholder visibility with the Agile aims of flexibility and responsiveness.

A governance framework or Agile governance model is used in conjunction with a standard Agile framework, such as Scrum. They work in two specific ways:

- They provide a wrapper for an Agile project by clarifying the processes that occur outside of development iterations (sprints). This includes providing clear criteria for the successful completion of project initiation and proper validation of the decisions and plan.

- They shift the emphasis of specific parts of the standard Agile process and highlight particular principles and techniques that need governance or support governance.

In today’s ever-changing world, organizations and businesses are keen to adopt a more flexible approach to delivering projects, and want to become more Agile. However, for organizations delivering projects and programs, and where existing formal project management processes already exist, the informality of many of the Agile approaches is daunting and is sometimes perceived as too risky. These project-focused organizations need a mature agile approach—agility within the concept of project delivery—Agile project management.

Learn and grow with your adoption of Agile. Only ever do what your team is comfortable with, ensure their voice is heard, and act on their requests. Encourage your team to adopt new and more valuable techniques when the time is right. Negotiate with the business and encourage them to understand what it means to be an Agile organization.

Enjoy the journey.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- What Is Agile? A Philosophy That Develops Through Practice

- Traversing Hybrid Project Management: The Bridge Between Agile and Waterfall

- Today’s Project Management Blueprint: A Comparison of Lean, Agile, Scrum, and Kanban

- The Project Management Blueprint, Part 2: A Comprehensive Comparison of Waterfall, DAD, SAFe, LeSS, and Scrum@Scale

- Agile, Scrum, and Kanban: What the Heck Do These Words Really Mean?

- CapEx 101: Resolving the Agile vs. Waterfall Conflict With Hybrid Methodology

- Agile Documentation: Balancing Speed and Knowledge Retention

- Whose Job Is It Anyway? A Real-world Guide to Agile Roles and Responsibilities

About the author

The former Head of Projects at Toptal, Paul’s project management expertise is focused primarily on agile methodologies.

PREVIOUSLY AT