Beyond Crypto: Blockchain Applications Deliver Enterprise Solutions

How are blockchain applications starting to help enterprises solve complex, costly problems? Saurin Patel, Client Partner at Toptal, provides a comprehensive, non-technical overview of blockchain as an enabling technology for the enterprise, and highlights recent use cases of the world’s leading companies harnessing the fledgling technology’s great potential.

How are blockchain applications starting to help enterprises solve complex, costly problems? Saurin Patel, Client Partner at Toptal, provides a comprehensive, non-technical overview of blockchain as an enabling technology for the enterprise, and highlights recent use cases of the world’s leading companies harnessing the fledgling technology’s great potential.

Saurin Patel

Saurin comes from a background combining extensive IT consulting and strategy experience. Having earned a BSE in computer engineering at Lehigh University, Saurin began his career at Accenture and Slalom Consulting, where he led global IT teams spanning the U.S., India, and Philippines. Subsequently, Saurin joined XO communications, where he reported directly to the CIO as Director of IT Strategy and Transformation. He was responsible for IT Solution Architecture, Enterprise Data Warehouse, Data Integration, and Business Intelligence systems.

Attention-grabbing cryptocurrency headlines eclipse the equally fascinating story of blockchain, the underlying technology. Amidst the noise, an emerging signal foreshadows the massive implications of the fledgling technology, and its potential to deliver groundbreaking blockchain applications.

Blockchain and bitcoin are related but distinct. As streaming video is to the internet, bitcoin is to the blockchain. Each example is an application of its underlying technology. The blockchain is the technology that enables bitcoin to exist. Other blockchains such as ethereum are similar but distinct, and enable their own set of applications, such as alternative cryptocurrencies.

Dozens of companies are investing heavily in blockchain, often pursuing real-world applications of blockchain to multi-trillion dollar industries. Boosted by leadership from blue chip technology and financial companies such as IBM, Microsoft, Bank of America and Barclays, this signal is gaining attention from other business leaders across multiple verticals. Increasingly, they recognize the familiar pattern of a revolutionary technology taking root.

Blockchain is an emerging, enabling technology

Similar to the PC or internet, blockchain poses transformative power to individuals and organizations, enabling them to achieve step-function improvements in productivity. However, instead of revolutionizing logistics or physical production, blockchain stands to redefine transactional processes—and the accompanying relationships—that exist between individuals, companies and governments.

In this article, and subsequent updates, our objective is to explore leading edge blockchain use cases, and to highlight emerging insights of blockchain technology applied to enterprise-scale problems. As a backdrop, we will briefly define the blockchain concept, and establish a basic framework for understanding its application. We will then explore recent real-world examples of the technology in action, as leading companies deploy blockchain to solve perennial challenges common to many industries.

The blockchain is a familiar concept

Fundamentally, the blockchain is a simple, familiar concept. It is a ledger, or a record. Similar to a written record, it has chapters—or blocks—of information, each added sequentially over time. While blockchain employs a variety of modern technology and security steps absent in a written text, its essence is similar to the first records and contracts etched by humans.

However, the blockchain fundamentally differs from all previous records, including more recent digital versions stored on PCs and across the internet, in two distinct ways.

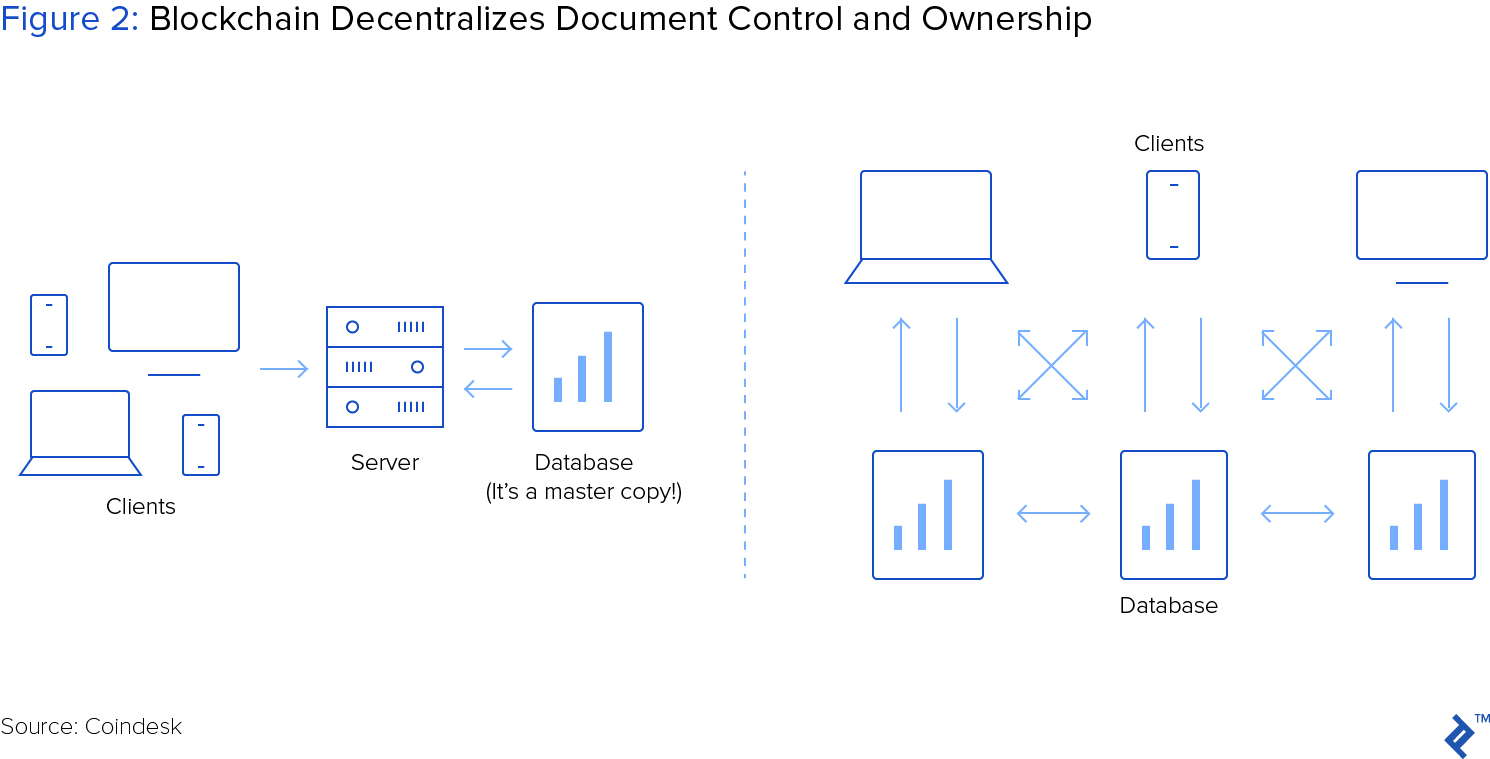

First, the blockchain is a shared record. Prior records were centrally controlled and updated, whether written documents by individuals, or digital files owned by database administrators. In every case, a centralized authority governed the record. By contrast, the blockchain exists in perfectly replicate form across multiple locations. In other words, it is a distributed record. No single participant owns the blockchain or dictates additions to it. Rather, updates are a function of consensus amongst participants.

Illustrating this distinction with a concrete example, Coindesk described Wikipedia, a record that resides on a centralized database, and for which, changes are only made by the database administrator. If the blockchain supplanted the digital backbone of Wikipedia, its database would reside on the computer of every curator, and changes would occur simultaneously across each database instance, as a function of a consensus process.

Second, the blockchain is immutable. It stores a history of itself back to the first entry, known as the genesis block. The identity of each new entry is created, in part, from the identity of the previous entry. Because every individual block is inextricably linked to all that precede it, changing its content or identity is essentially impossible. The upshot of blockchain immutability is its unprecedented security—a tamper-proof record, impervious to assaults by bad actors.

Contextualizing blockchain within the enterprise, it is helpful to view it as a data store, according to Toptal blockchain engineering expert, Dan Napierski. Viewed as a data store, blockchain presents trade-offs versus traditional business databases. As with all tools, it must be applied to the right job. According to Napierski:

“Traditional databases make data available for retrieval and updating by those with credentials approved by the database administrator. They are often designed for efficient querying across the entire data set. Although tools exist to search for data within the blockchain, it is not designed for fast queries. Further, as an append-only database, blocks cannot be changed once committed to the blockchain. The blockchain only changes by the addition of new blocks. Accordingly, blockchain is not designed to perform some of the standard operations of a traditional database, such as updating and deleting information. ”

Elaborating on the potential for corporate applications, Napierski noted two distinct advantages of a blockchain database:

No third parties. Blockchain eliminates the need for an intermediary third party, such as a bank. Both transacting parties can trust that information added to the blockchain can not, and will not be changed. Large corporations could directly interact with each other, writing their own contracts with no need to involve third parties, or any other intermediary to assert correctness.

Faster consensus. Blockchain allows participants to reach consensus, or settle the transaction quickly. Multi-day processes channeled through intermediaries are reduced to minutes.

So, for shared records such as contracts, the blockchain fundamentally transforms ownership, transparency, security and consequently, the value of the records and the process they govern. In the context of a shared record or contract, blockchain reframes the concept of trust. Succinctly captured by The Economist, the blockchain lets people (or companies) who have no particular confidence in each other collaborate without having to go through a neutral central authority. Simply put, it is a machine for creating trust.

Two types of blockchain: public and permissioned

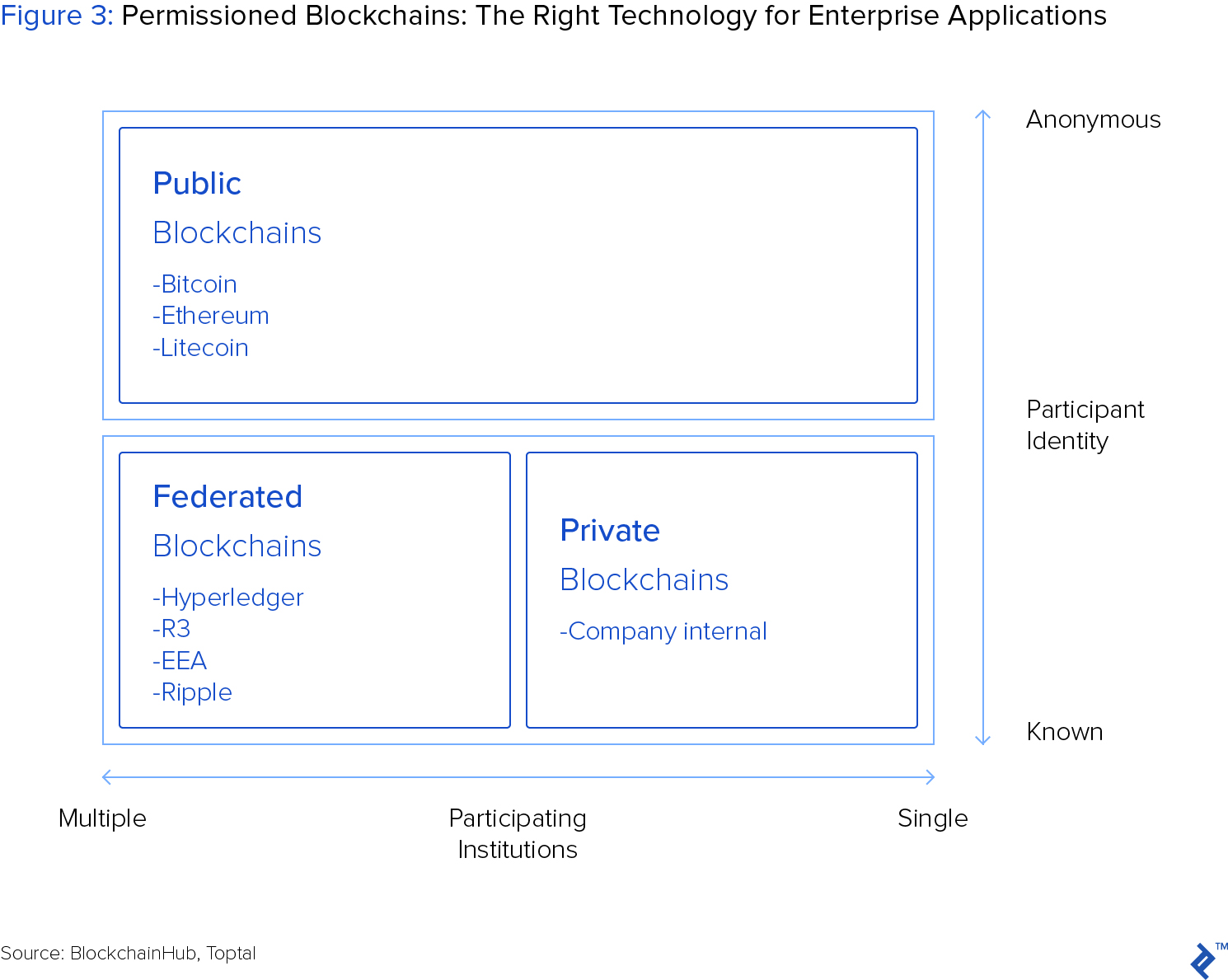

There are two types of blockchain: public and permissioned. The public blockchain, also known as “permissionless,” is open to anyone. Underlying popular cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin and ethereum, a public blockchain is open to anyone and all participants are anonymous.

Anyone can download the blockchain (for example, the blockchain underlying bitcoin was about 149GB at the end of 2017), read all historical transactions, use their computer to validate new transactions, and add new transactions to the network without ever disclosing their identity. However, within the context of enterprise applications, which focus on a finite cast of participants, public blockchains are not relevant.

Contrary to public blockchains, permissioned blockchains are open to a limited number of participants whose identities are all known. There are two forms of permissioned blockchain: private and semi-private. Accessibility beyond a single organization distinguishes these two structures; the private blockchain operates within, while the semi-private operates between organizations.

While both structures are theoretically relevant to the enterprise, the semi-private (also known as federated or consortium) blockchain holds more practical potential, as most companies transact with multiple organizations. Unless specifically noted, all references to the permissioned blockchain will assume the semi-private version.

Unlike the public blockchain, which has no defined leadership, the permissioned blockchain designates several participating parties with the authority to control the consensus process, the mechanism by which transactions are verified.

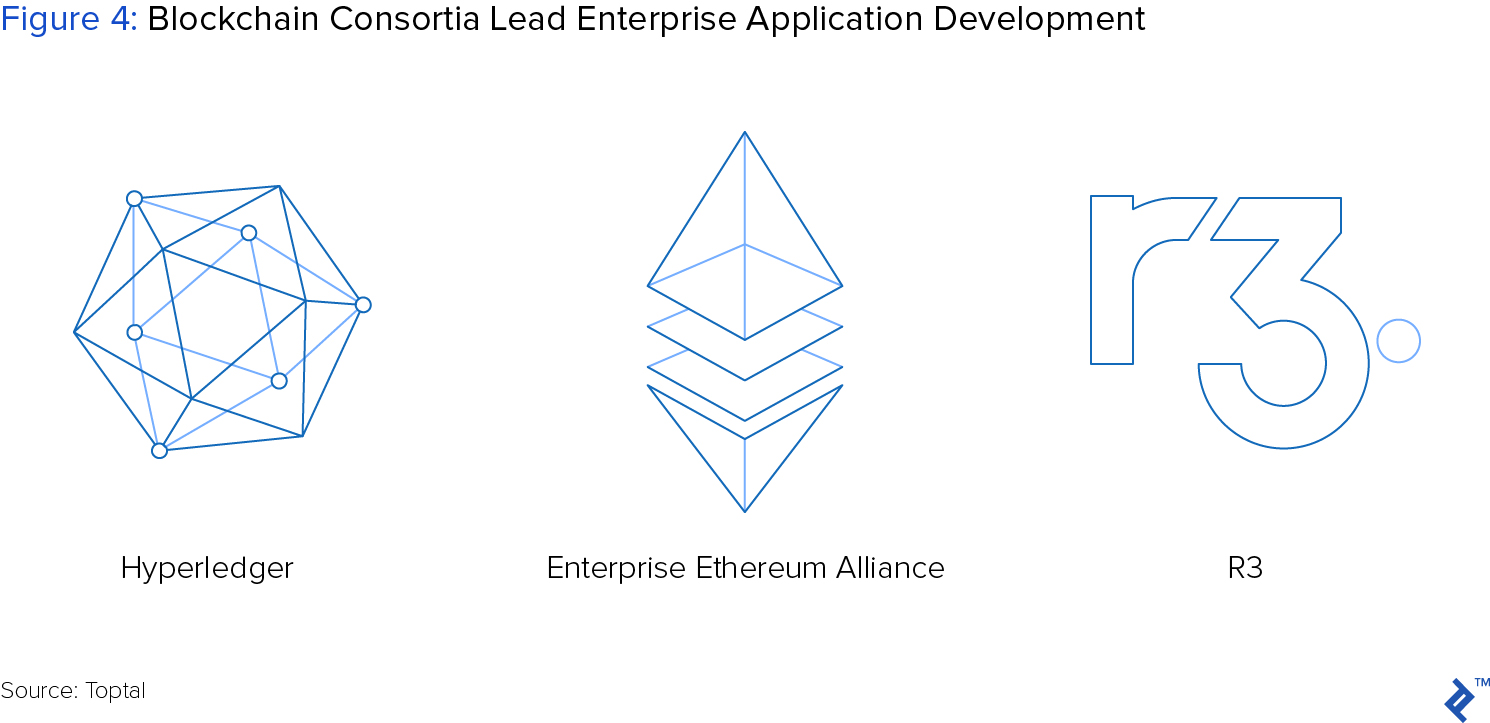

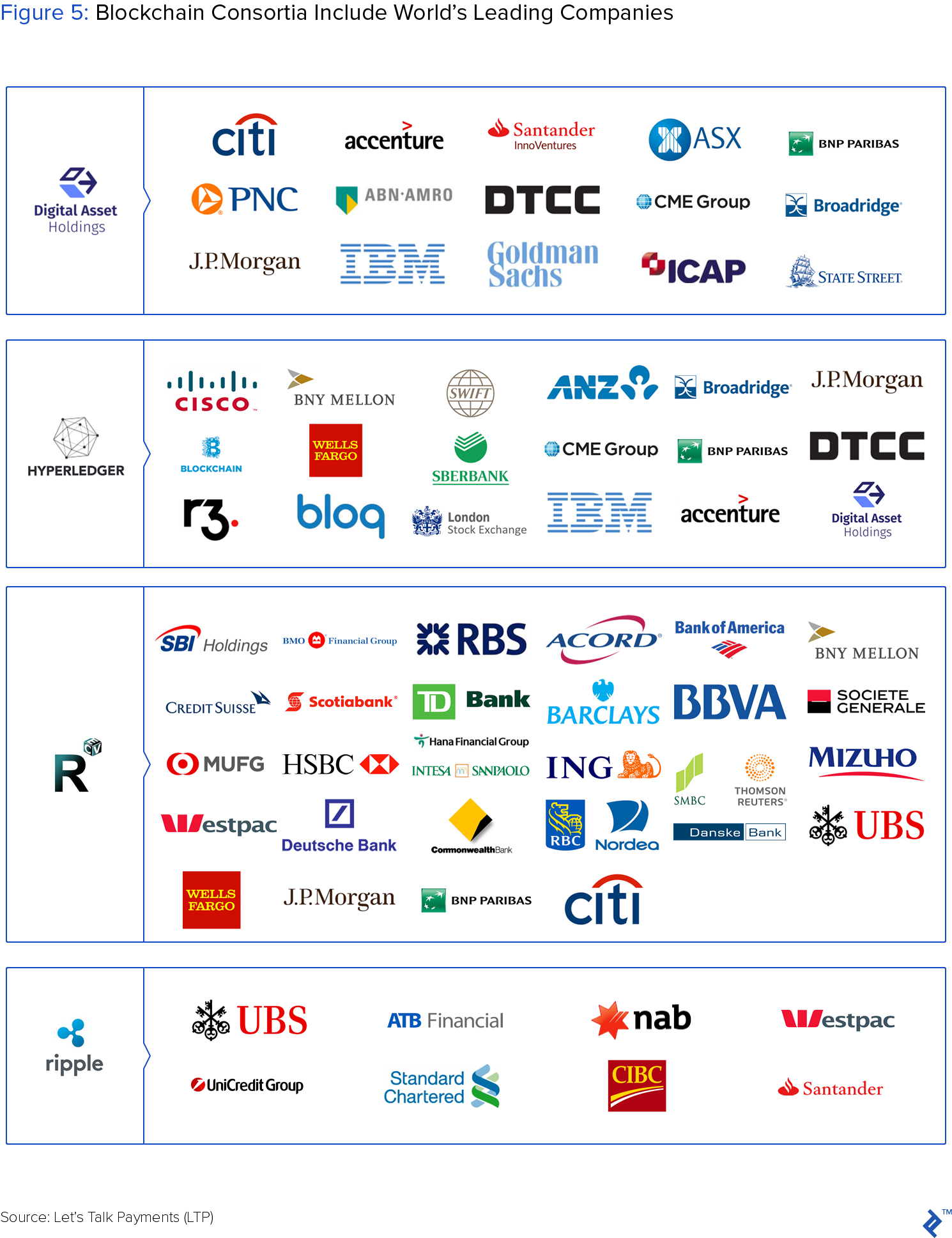

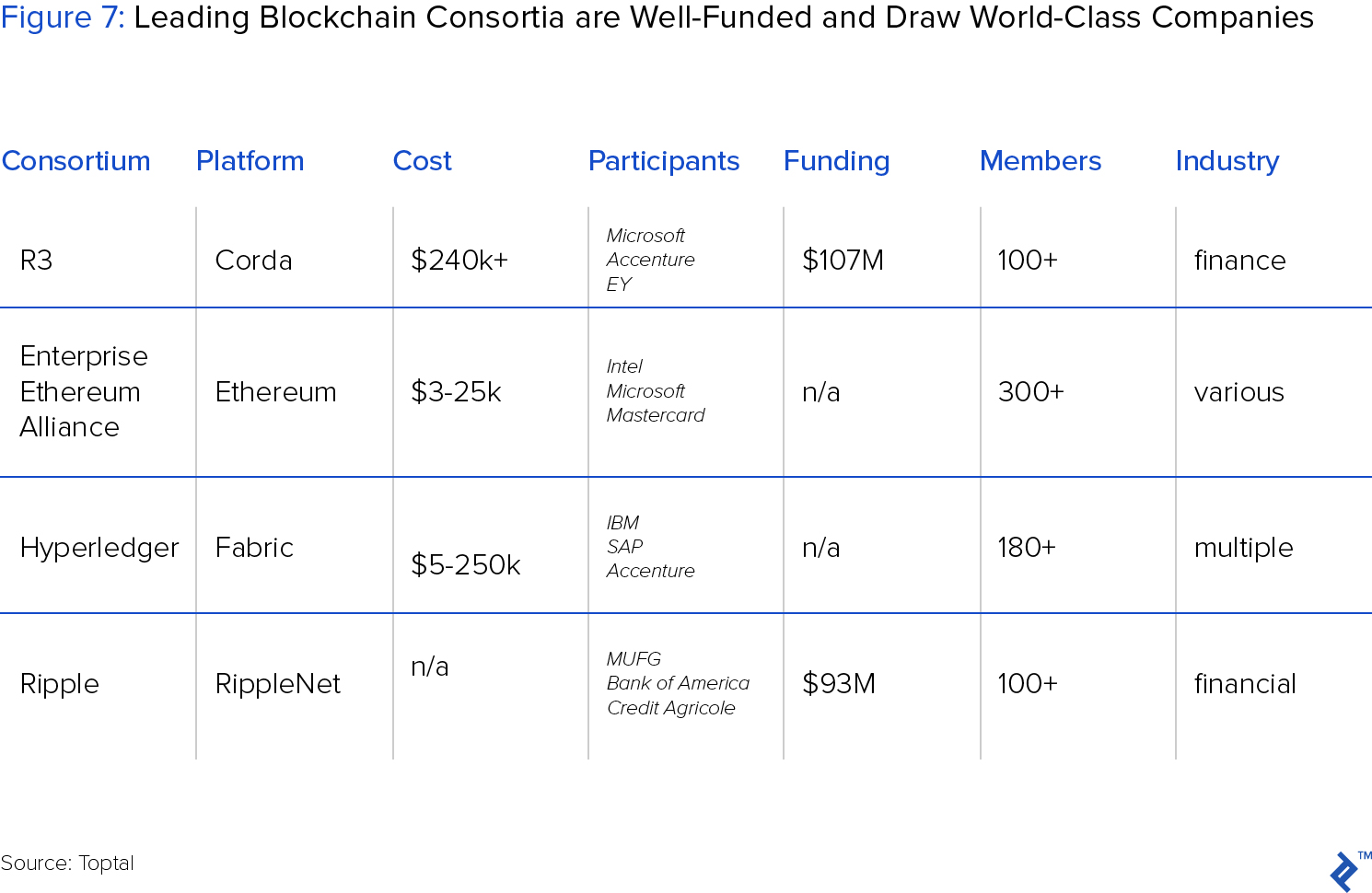

Evidence of commercial potential for permissioned blockchain networks, several significant consortia, such as Hyperledger, Enterprise Ethereum Alliance and R3, are emerging to equip participating members with robust technology. These consortia function to enable collaboration amongst transacting industry participants, allowing them to architect the blockchain operating standards and designate leadership best suited to serve participant needs.

While consortium membership isn’t necessary to pursue enterprise blockchain applications, it is the preferred route for many organizations. Members benefit in at least 2 distinct ways.

Influence. Members can influence the design and governance of the underlying technology, directing it to solve problems unique to their business model or industry ecosystem.

Focus. Members join a defined network, often focused on solving a specific business challenge (ex: decreasing transaction costs) or on developing a particular form of blockchain technology.

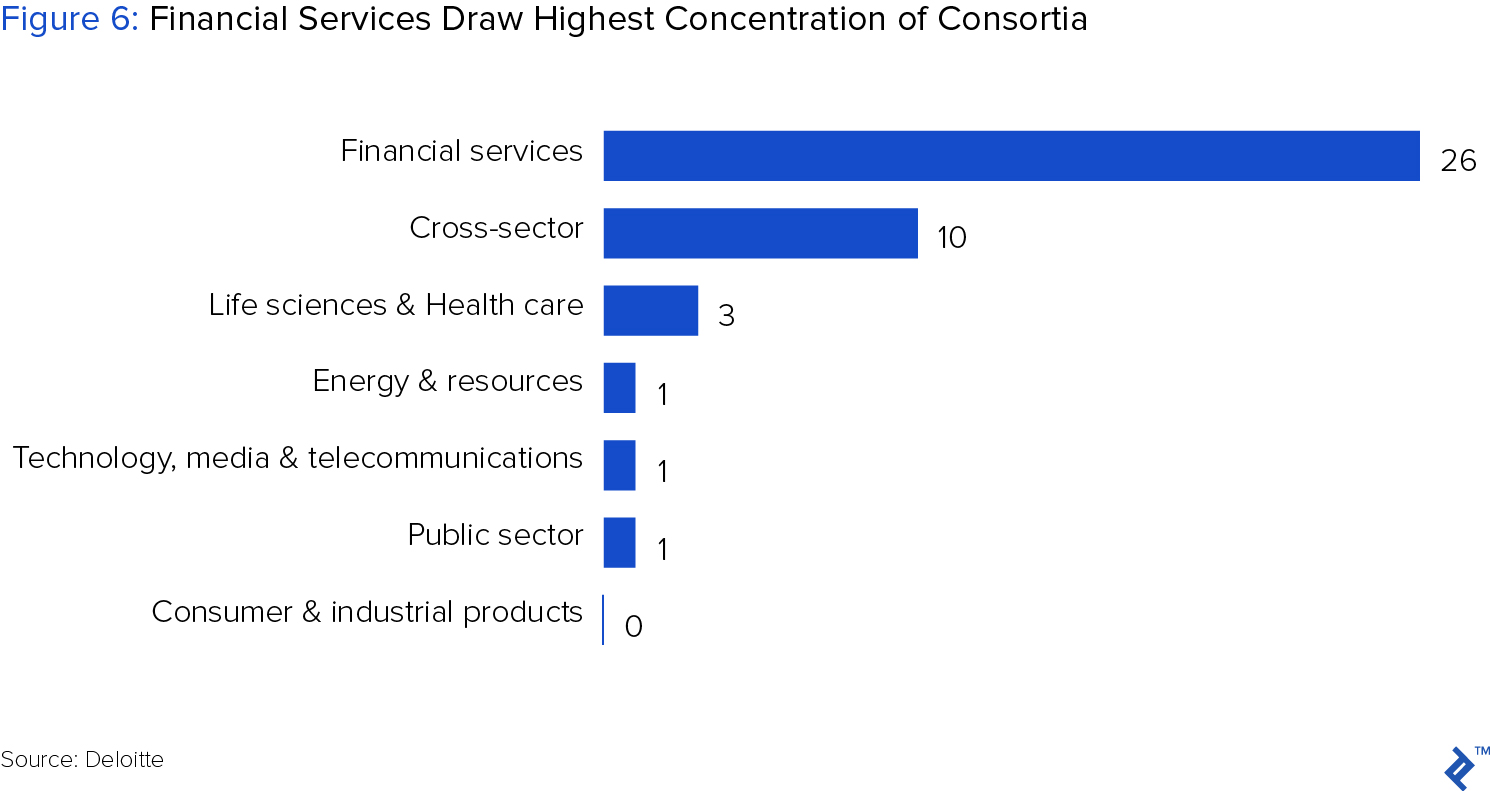

Accounting for more than 50% of the consortia and their participating members, financial services remains the priority industry for blockchain application development. However, other industries that depend on trusted transactions and experience high counterparty risk are also mobilizing. Notably, supply chain applications for food, healthcare and other high-risk or high-value products are gaining support across multiple verticals.

The consortia landscape is in its infancy, and it will likely evolve as rapidly as the blockchain technologies developed by its participants. Currently, about 40 consortia exist, but only a few boast standout membership, funding and leadership.

Even so, seemingly established leaders are still vulnerable to shifting forces, as Hyperledger recently witnessed, suffering nearly 10% attrition of its membership base. Earlier in the year, leading banks including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase left R3. These departures are not marks against either consortia, but a symptom of the rapidly evolving needs of their participants. Further, many companies, such as Intel, Microsoft and Accenture participate in multiple consortia.

Whether and which consortium to join presents a new decision for enterprise leaders. According to a Deloitte study, amongst executives familiar with blockchain technology, 18% are already part of a consortium, with 45% likely to join, and 14% considering forming one.

Real-World Blockchain Applications

With some background terminology and a framework in place, we can now explore the real-world applications of blockchain in the enterprise. Mirroring consortia concentration in finance, cross-industry and life sciences, most companies are focusing heavily on complex transactions with high potential risk.

Supply Chains: Failures Are Costly and Hard to Trace

Manufacturing companies rely on vast, often global, supply chains to remain competitive. Of top concern—particularly with products that directly impact customer health and safety—quality assurance and traceability are paramount objectives. However, as companies scale, their supply chains become increasingly complex, often relying on a vast supplier base and multiple handoffs before components reach their facilities.

Several headline cases highlight the consequences of supply chain opacity, and the value blockchain offers by fully illuminating the chain from origin to customer. In 2015, an e.coli outbreak at Chipotle sickened 55 customers, shut down operations, and erased $8 billion of equity value within 3 months of the outbreak. In 2009, Toyota recalled 4 million vehicles due to a faulty gas pedal, resulting in an estimated $2 billion revenue reduction and a 15% drop in the share price.

Although blockchain couldn’t have prevented the failures at Chipotle and Toyota, it could have reduced the time, expense and complexity of identifying their root causes. Quickly linking defective products to source suppliers, both companies could have selectively targeted tainted products, sparing the costly, drastic recalls.

Farm to Shelf: Walmart Tracing Pork Supply in China

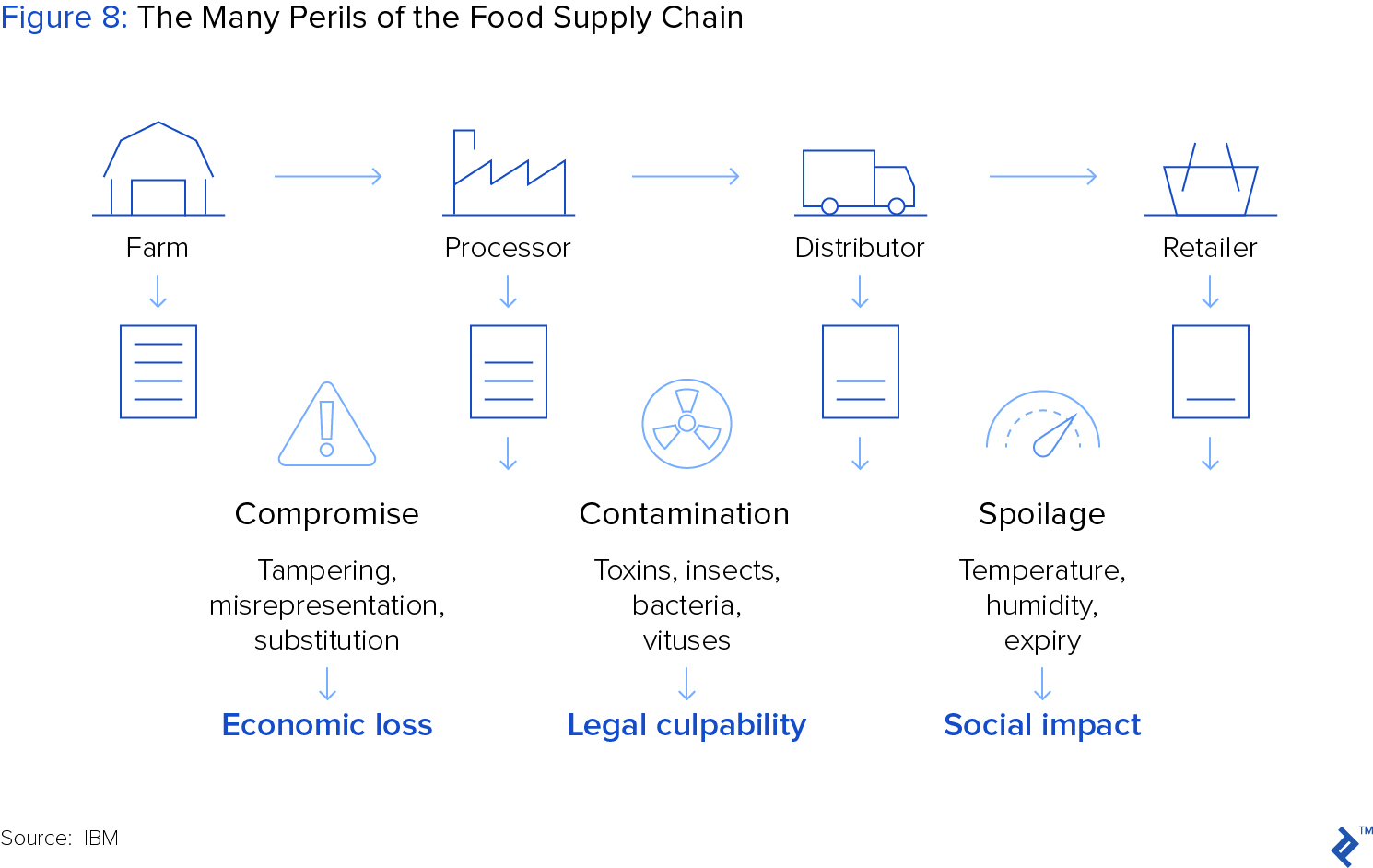

Food supply chains for multinational retailers present a high-stakes challenge. Every day, billions of customers expect products to be pure, clean and safe to eat. Mistakes are costly, and sometimes deadly. Contaminated products are notoriously difficult to trace, often forcing companies to respond with severe measures—including recalling all product or shutting down operations. In addition to risk from errors, opportunities abound for fraudulent behavior, leaving companies, and their consumers at risk.

To picture the blockchain use case, it’s helpful to illustrate the food supply stages, each presenting multiple failure points:

- Production: growing plants, raising livestock, harvesting wild species

- Processing: converting raw materials into finished goods

- Distribution: transporting finished goods to point of sale

As for all supply chains, for food there are two paramount concerns: provenance and chain of custody. Provenance refers to the origin of each ingredient. Chain of custody refers to the unbroken path a product—and its upstream ingredients—follows from the beginning of the supply chain to the customer. The chain of custody captures all the processes of converting, combing and moving product components as they culminate in the finished product at the point of sale.

Walmart applied blockchain technology to improve transparency of its pork supply in China. A recent recall of 100,000 tons of contaminated Chinese product, followed by Walmart’s global effort to improve food safety set the stage for their blockchain pilot.

In partnership with IBM and Tsinghua University, WalMart used Hyperledger to link digital records of each RFID-tagged animal to the blockchain. Tracking critical information, including farm origination details, batch numbers, factory and processing data, expiration dates, storage temperatures and shipping details, the blockchain illuminated the chain of custody of each animal to all parties throughout the supply chain.

Highlighting the pilot’s impact, Frank Yiannas, VP of food safety at Walmart noted the company can now verify if product is authentic and safe, and when it expires. Further, if a food contamination issue arises at the farm or factory, they know which products to recall and which may be left on the shelves.

Following the success of Walmart’s pilot, JD.com—China’s largest e-commerce company—partnered to develop the Food Safety Alliance, drawing participation from Dole, Driscoll’s, Golden State Foods, Kroger, McCormick and Company, McLane Company, Nestlé, Tyson Foods, and Unilever. Undoubtedly, further blockchain applications within this alliance will guide the path for other global food companies to improve transparency within their supply chains.

Trade Finance Transactions Simplified and Expedited

Traditionally document-intensive and reliant on bank intermediaries, Trade finance presents a particularly attractive application for blockchain. Highlighting a blockchain application use case, trade finance is relevant to companies engaging in complex transactions with high counterparty risk.

According to the World Trade Organization, an estimated $18 trillion of goods flow across international borders annually, enabled by some form of trade finance—credit, insurance or a guarantee. Trade finance captures a variety of activities designed to decrease risk between trading counter-parties, particularly those that have not previously transacted.

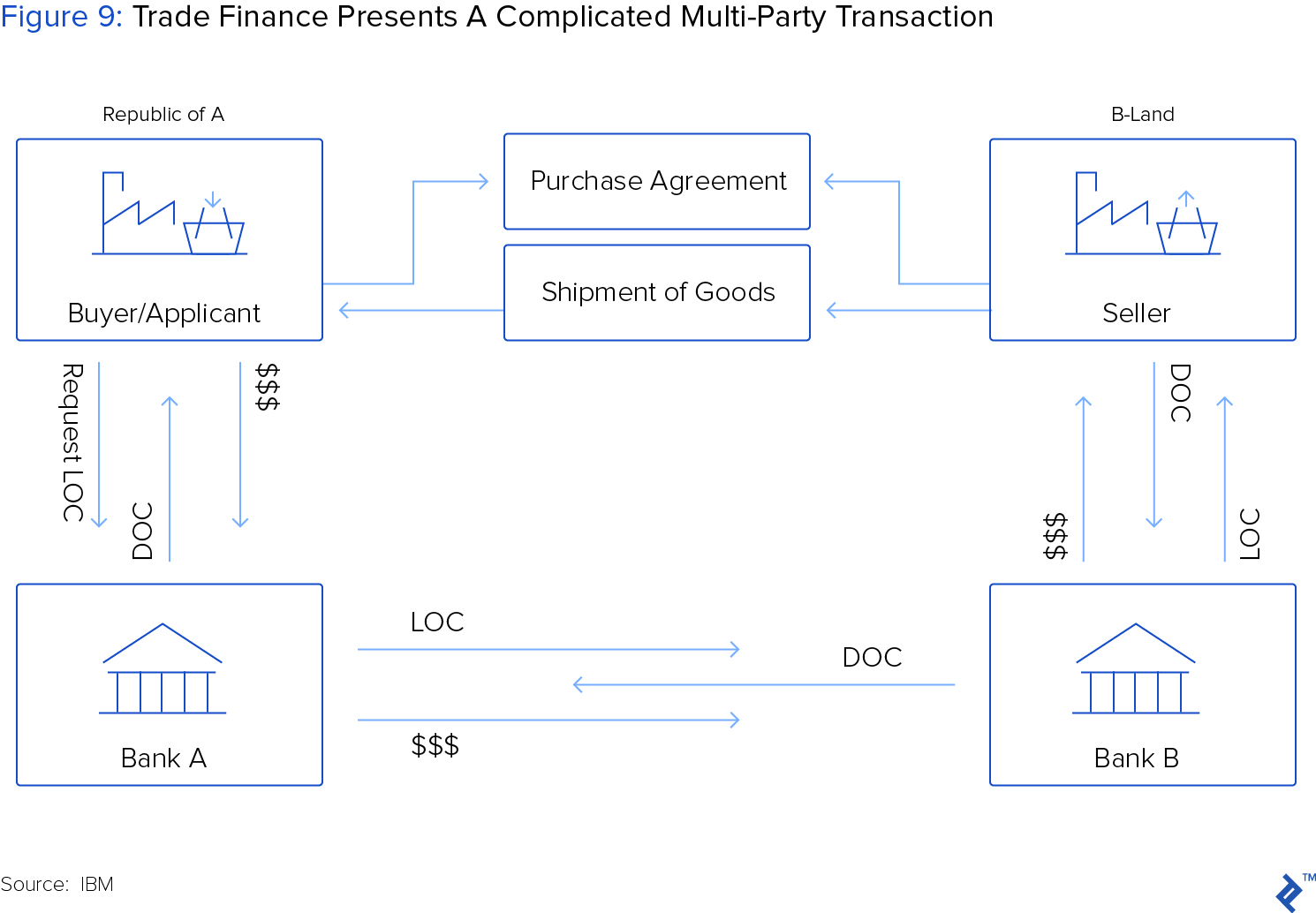

Greasing the wheels of the trade finance machine, the letter of credit insures a seller gets paid. The buyer’s bank, typically working in concert with the seller’s bank, issues a letter of credit. This letter ensures the seller receives payment once its goods are received, especially in the event the buyer becomes insolvent. A typical trading scenario, and its requisite document and money flows highlights the complexity of a typical trade finance transaction.

Treasury departments within global companies manage such transactions, relying on centralized, often inefficient processes. Through SWIFT alone, one of the leading global financial networks, 40 million transactions flow annually between counterparties.

Commenting on his experience with such transactions, Toptal finance expert Alex Graham previously spent years working in corporate treasury, where he witnessed delays, inefficiencies and costs of checkpoint incumbent payments systems like SWIFT.

By contrast, Alex noted that the increasingly popular blockchain platform Ripple makes payments become an instantaneous flow, with lower fees and risk (credit and liquidity) and gives more process transparency. Further elaborating, Graham noted:

“Innovations such as Ripple give the corporate treasurer more comfort and time to focus on value-additive activities, away from settlements and reconciliations headaches common to legacy processes.”

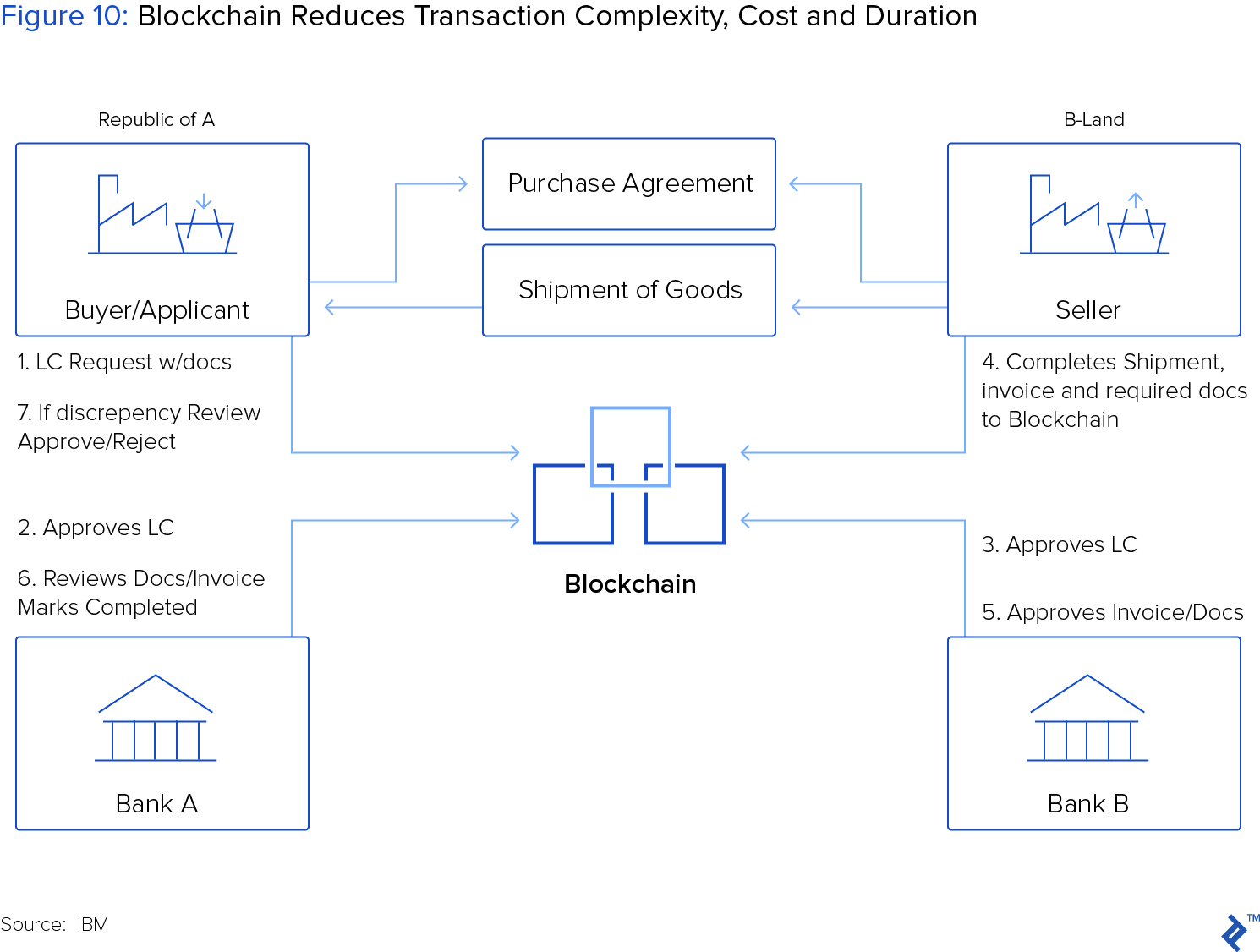

In a related effort, Bank of America partnered with HSBC and the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore (IDA) to simplify and expedite the trade finance process using Hyperledger. Instead of sequentially exchanging letters of credit, as trade partners do now, all parties involved in a trade finance transaction could share information on the permissioned ledger. Once an importer posts a letter of credit to the ledger, a sequence of conditional events follows, each automatically recorded on the blockchain and culminating in a settled trade.

The partners confirmed the pilot’s success, noting the proof of concept shows potential to streamline the manual processing of import/export documentation, improve security by reducing errors, increase convenience for all parties through mobile interaction and make companies’ working capital more predictable.

In a similar application, Microsoft’s blockchain team sought to simplify the letter of credit process for the company’s treasury department. As part of its routine trading, Microsoft uses hundreds of letters of credit annually, a process that lasts five days, costs $2,500—$15,000, requires 15 distinct steps, and most critically, suffers an error rate as high as 50% due to manual mistakes.

Building on the success of Bank of America’s existing blockchain pilot, Microsoft partnered to solve its own letter of credit challenge. Deploying a similar private network, built on the ethereum blockchain, the joint effort dramatically improved the letter of credit process, reducing the duration to minutes, the required steps from 15 to four, and the error rate to 0%.

Parting Thoughts: blockchain applications are just getting started

Evident in the emerging consortia, and modest scale of enterprise pilot applications, blockchain applications are fledgling within the enterprise. However, these experimental projects do not signal a theoretical or speculative technology.

The investment behind, and expectation for, blockchain in the enterprise is substantial and will only increase. The projects profiled above, and those detailed in subsequent articles, will likely trace a line of torrid growth over the coming year, as companies build on these early successes. For any executive seeking insight into this game-changing technology, the story that unfolds will be undoubtedly fascinating.