Black Swans 3: How Challenges Lead to Breakthroughs

The world is reinventing itself after COVID-19. Through lessons from national economies, companies, and individuals, this piece presents critical considerations for helping our cities or countries and adapting our companies and careers.

The world is reinventing itself after COVID-19. Through lessons from national economies, companies, and individuals, this piece presents critical considerations for helping our cities or countries and adapting our companies and careers.

Data scientist and venture capitalist who has invested in 50 global tech companies. He is the Chief Economist at Toptal.

PREVIOUSLY AT

Read the first two installments of this series:

- COVID-19 Lessons: Organizational Adaptability, Going Remote, and Black Swans

- Black Swans and the Paradigm Shift of Remote Work – COVID-19 Lessons, Part 2

Eight years ago, I was in a meeting in Medellin, Colombia, in which one of the city’s leaders discussed plans to become a leading global technology hub as part of its post-Escobar renaissance. Medellin had once held the tragic honor of being the most dangerous city on earth as measured by murders per capita; it subsequently received international acclaim for its transformation into a rising hub of innovation and technology. While discussing how to continue this momentum, the unnamed leader said to us, “One day, we’ll make this the greatest city on earth, precisely because we know what it meant to be the worst.”

That harnessing of forward momentum and innovative thinking, using lessons from one of history’s most tragic moments, was the main reason why I chose Medellin as my non-US base while building my venture fund. Visitors from Israel often remarked on the parallels with their own country in terms of redirecting difficult experiences into global technological leadership. Today, Medellin is first among all major Latin American cities and high among all global cities in containing the pandemic, and it is now turning its efforts to helping other cities around the world. I have no doubt that the relentlessly innovative and resilient spirit that was born out of the cartel crisis uniquely positioned the city to confront the current one. Not incidentally, the other city in the region that has most distinguished itself during COVID-19 is Buenos Aires, which previously saw the worst economic collapse in the Americas.

In the subsequent years with my venture fund, I noticed that one of the two most predictive factors of success in startups was whether they had been born of a specific problem or difficult situation the founder had directly experienced. (The other factor was the ability to recruit top talent.) Those two variables alone crushed all others combined when predicting success.

This article explores how to land on the right side of the equation as the world recovers from and reinvents itself after the COVID-19 black swan event. We will examine national economies, companies, and individuals for complementary points of view on the same underlying truths. They are all parts of the same nested system, and we should think on all three levels as we help our cities or countries with their economic recovery plans and adapt our companies and careers.

The Counterintuitive Consequences of Crises and Windfalls

Prior to switching to venture capital, I helped companies react to market crises and knew many people who lost their jobs (and more) during the subprime financial crisis. Many of them later described that experience to me as the most important moment in their professional lives. Not the “best”—they weren’t romanticizing it—but with time, they came to view it as a rare event that packed decades of wisdom into a few years. Those who graduated into the crisis have likewise credited the experience with accelerating their development as entrepreneurs in discipline, focus, and the ability to navigate change and uncertainty.

The tragic flip side of this coin is actually windfalls, which most would consider the exact opposite of crises, yet have also been shown to have devastating consequences. Countries that strike it rich with natural resources become not only poor but humanitarian disasters. Companies that strike it rich with a tremendously profitable product often become more cautious and defensive in their approach to innovation and growth and hence become vulnerable to upstart competitors. Lottery winners are far more likely than other people to eventually declare bankruptcy. Another critical factor in choosing Colombia for my non-US base was the country’s relative lack of oil wealth versus other Latin American countries. Its neighbor Venezuela, whose capital city currently suffers the most murders per capita in the world, has the most. While it would be a stretch to agree with Hamlet that “there is nothing either good or bad,” the evidence makes it difficult to not conclude that our notions of good and bad in both life and business are simplistic.

National Economies: Why COVID-19 Is an Opportunity for Rebirth

There is a fascinating paradox in development economics whereby a country’s greatest challenges and difficulties contribute directly to its main competitive advantages, while factors seemingly in its favor—such as natural wealth—hold it back. Michael Porter’s book The Competitive Advantage of Nations, the largest study on the development of national economies, explores how a country’s most promising economic attributes tend to realize their potential only when colliding with what that country lacks most. In other words, it’s not what you have and what you don’t have, it’s how to fit those two pieces of the puzzle together.

COVID-19 creates a vivid example of this with Colombia’s race to produce a $1,000 ventilator. Colombia has world-class engineers and medical professionals but lacks medical equipment and, unfortunately, money. The collision of these two circumstances, spurred by the focus and urgency of the crisis, is yielding a high-quality ventilator at a fraction of the prevailing global cost in a matter of weeks, with many of those involved having no previous experience with medical devices.

Porter says, “Innovation to offset selective weaknesses is more likely (to succeed) than innovation to exploit strengths,” highlighting the advantage of a problem-driven—rather than an idea-driven—approach to development. This results from two key advantages that problems (and crises) offer that we might lack under more comfortable circumstances: focus and urgency. He states, “Selective disadvantages create visible bottlenecks, obvious threats, and clear targets for improving competitive position. An intermediate level of pressure, involving a balance of advantage in some areas and disadvantage in selected others, seems to be the best combination for improvement and innovation.”

I have witnessed this phenomenon up close in emerging tech hubs around the world. There is an important lesson in these findings for all of us as we think about how our world can best rebuild from the economic destruction brought about by the pandemic. What we are losing now was built in the first place as a result of what we had previously lacked. In the past months, we have all vividly witnessed what our national economies have and lack the most, and we should be taking both signals as pieces to be fit together.

The reverse of the principle applies. The worst crises often happen when something we thought was a strength turns against us. The subprime collapse did so with the interconnectedness of our economic system; COVID-19 is now doing so with the physical interconnectedness of the world. In both cases, negative factors rapidly compounded by taking advantage of our strengths. It should come as no surprise that rebirth will come from using our weaknesses to compound our strengths.

Companies: How 2008 Changed the Way Organizations Innovate

The subprime crisis provides our most recent dataset on the dynamics of innovation during black swan events at the company level. Innovation can be difficult to quantify as it often entails the very things that fall outside what we typically measure in business, but R&D expenditure provides at least a proxy of how companies reacted to the crisis.

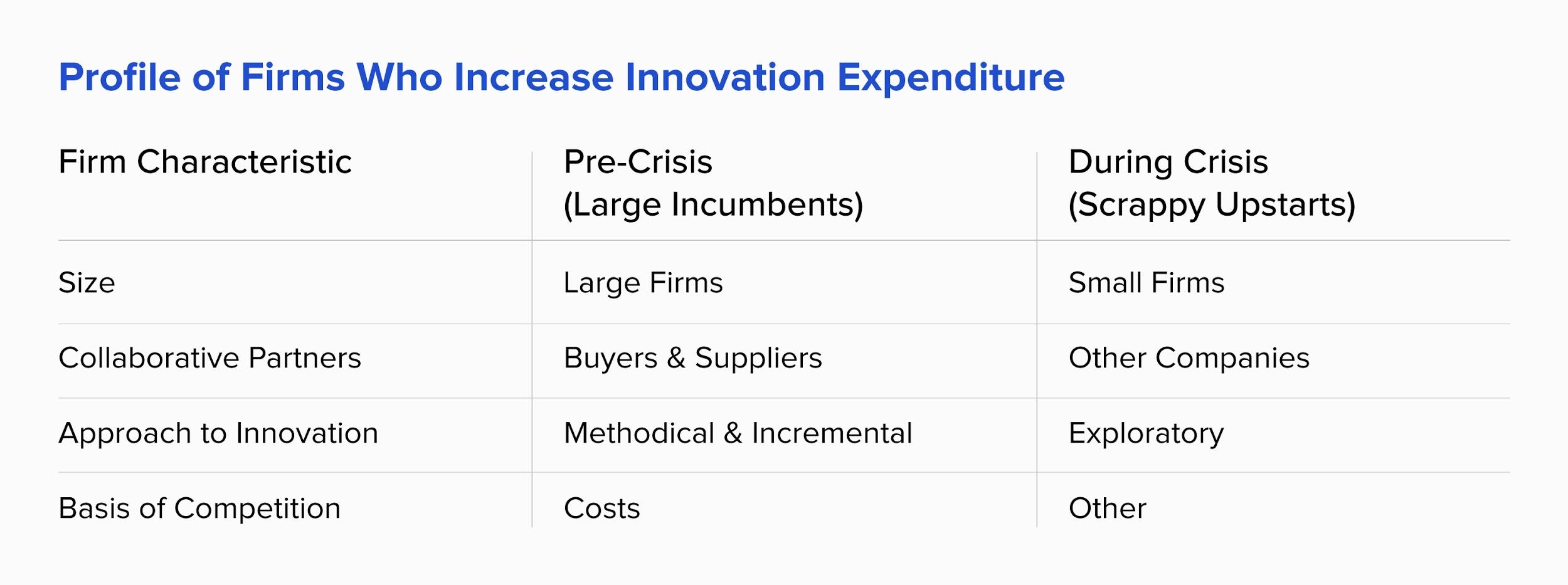

The studies have found that it is the nature, rather than level, of innovation that changes during crises, as well as who the innovators tend to be. Prior to the subprime crisis, using R&D spending as the proxy, large incumbents led the way and increased their innovative activities. Such firms follow methodical and incremental innovation strategies and collaborate with their most direct stakeholders in terms of those they were buying from (suppliers) and those buying from them (customers).

During the crisis, however, such firms reduced their focus on innovation, perhaps due to financial pressure from their higher fixed costs. In doing so, they may have set themselves up for further difficulties as certain types of companies have been found to increase their focus on innovation in times of crisis. These companies are the scrappy upstarts—smaller than those who were most aggressive with innovative activities pre-crisis, collaborative with other businesses rather than only suppliers and buyers, explorative of new marketing opportunities, and less likely to compete on costs. It is striking that those companies less likely to compete on costs take the lead here—crises are when one would generally expect customers to become particularly cost-conscious. It has been concluded that “what matters are not large size and internal R&D, but flexibility, collaborative arrangements and exploration of new markets.” (Also taken from Technological Forecasting & Social Change, cited above.)

Airbnb, for example, was founded in 2008—in the midst of the Great Recession. Instead of cursing its luck, it took the moment as an opportunity to rapidly innovate and shake up the accommodations market. Time will tell how well the company weathers the current crisis due to the distinct impact on travel, but its initial approach during the Great Recession propelled it along an extraordinary trajectory toward Fortune 500 status.

The difference in collaboration and nature of opportunities considered is telling. The scrappy upstarts collaborate with those who are not suppliers or customers (i.e., those they might not otherwise have thought to collaborate with), employ the optionality-driven approach of testing new markets, and use new technologies as a key driver. These findings will surprise no one who has worked with startups. They should also serve as a warning to larger companies regarding where they prioritize innovation while cutting in their budgets to weather the downturn. This may be the worst possible moment to make such cuts, as it cuts you off from the disruptive solutions that are born out of the crisis.

Future research could more closely explore the extreme impact of innovation in times of crisis by estimating the value—in aggregate sales or market valuation—of those products and companies born out of crisis moments. I would hypothesize that such a cohort-based study would reveal that the impact of every dollar (and hour) invested in innovation during crises brings a disproportionate payoff. The failure rate of projects may be higher, but following the principles of agile development and optionality limits their downside.

Alexander Field of Santa Clara University, for example, calls the 1930s—which included the Great Depression in the US—the “most technologically progressive decade of the century.” He finds that many of the new products and technologies created during this decade—forward leaps in aviation, combustion engines, and chemical engineering—laid the groundwork for the postwar economic boom. Focusing too narrowly on the input of R&D spending risks overlooking the complex realities of how innovation occurs and is funded within smaller, more exploratory companies.

Such businesses are sometimes termed “ecosystem businesses” due to their network-based designs, both internally and in the larger networks of talent and collaborators, and are noted in the Harvard Business Review for having a distinct competitive advantage during crises. Ping An, for example, is the world’s second-largest insurance company and thrives by dividing itself into distinct and heavily autonomous business units. These units can build upon each other through cross-selling and collaboration in good times and provide optionality across diverse financial markets in difficult times. The HBR notes, “They are not business units inside a corporate bureaucracy—instead, they are run as autonomous business ventures. As a system, Ping An can afford to lose in one bet but then win in another. In other words, an ecosystem advantage enables dynamic revenue diversification.”

Crises serve in many ways as an amplifier for the strengths and weaknesses a company already had. Those that had already been playing defense by erecting various barriers around more static competitive advantages—and with poor team dynamics—more rapidly flounder. Those that had already been exploratory, network-driven, horizontal rather than hierarchical, and prioritized positive team dynamics will find that their moment has arrived.

Individuals: The Power of Learning and Networks

It is people who drive these national and organizational transformations. The most successful people I’ve known have nearly all owed their success to crises or hardships, whether systemic (the subprime collapse) or more personal (losing a job with a young family to support or fleeing their home country during a revolution). They often dismiss their own supposed innate abilities, speaking instead of situations in which they were compelled to rise to the occasion and make an extreme impact.

These people exemplified self-awareness and empathy, greeted crises as part of an ongoing evolution of their careers and companies, believed in collaboration over zero-sum competition, and asked how they could most help others rather than merely themselves. The global talent economy allows us to embed our companies and careers within ecosystems that are constellations of even greater ecosystems, leveraging them to explore, validate, and pursue new possibilities. None of us can confront this new normal alone. Your ecosystem becomes a safety net in the immediate term and a launchpad in the medium term.

I spent years working with the global financial community to avoid black swans by day, helping to build a pan-American cultural organization by night. The subprime crisis left me asking: What was the point? The cultural organization closed for unrelated reasons. I had defined myself by those two endeavors and felt defeated and lost. The world seemed to require a revamp in its conception of work and the global flow of ideas. That crisis moment clarified my mission in life and armed me with the lessons and pain threshold to co-found the world’s first venture fund predicated on the global talent thesis (an adventure that crossed my path with Toptal and Staffing.com).

Beyond bringing focus and urgency, I believe crises best yield breakthroughs because greatness requires being your true self—crises tear away the facade of who you felt pressured to be. This is the same reason why I love remote work—it allows companies and professionals to immerse themselves in new ideas, markets, and relationships, discovering their true selves and what they can best offer the world.

Conclusion: What You Do with Crisis, How, and with Whom

This series has offered lessons from my prior experience for interpreting how black swan events transpire and how this applies to COVID-19 and its resultant shift toward remote work. I hope this final installment ends on the hopeful note that such moments, when approached in certain ways, can bring tremendous achievements and breakthroughs. Crises and severe challenges, when channeled through the right factors, are the most powerful drivers of innovation and growth yet identified. However, this only occurs under specific circumstances. Individuals, companies, and countries achieve it when:

- They find the angle to meet these challenges with their greatest strengths. These strengths run far deeper than an individual’s current title or a company’s current product.

- They foster optionality through constant exploration of new financial markets while building new technologies.

- They take a network or “ecosystem approach” to business rather than attempting to go it alone. Companies and individuals thrive most within collaborative networks that allow for rapid identification and testing opportunities—the global talent pool afforded by virtual work is not just a means to contain the pandemic but also a way to build the companies and innovations that will lead us out of it.

This will not be the final black swan event in our lifetimes. Therefore, the distinction of “short-term vs. long-term thinking” is insufficient. We need to evaluate our plans and time horizons within supercycles, based on the understanding that risk and reward will dramatically cluster around key moments of crisis and change every 10 years or so. With enough planning and proactive adaptability, the next crisis can be a springboard rather than a hurdle. None of that makes the current one any easier, but it does offer a reason for optimism. One day, we may look back on it when someone asks us how we got to where we are now.

Erik Stettler

New York, NY, United States

Member since November 21, 2017

About the author

Data scientist and venture capitalist who has invested in 50 global tech companies. He is the Chief Economist at Toptal.

PREVIOUSLY AT