Digitally Divided: Zoom-less Rural America Looks to Close Broadband Gap

Poor investments and service monopolies have blocked many Americans from high-speed internet access. Renewed interest in boosting broadband might finally bridge the access gap.

Poor investments and service monopolies have blocked many Americans from high-speed internet access. Renewed interest in boosting broadband might finally bridge the access gap.

Michael J. McDonald

Michael J. McDonald is an award-winning journalist who has worked at Bloomberg News and Thomson Financial. He is a Senior Writer at Toptal.

Lincoln County, Wisconsin, is located between Minneapolis and Green Bay, where vast tracts of farmland give way to the state’s remote Northwoods region. With its lakefront homes and snowmobile trails, the county is a natural destination for working urbanites looking to escape coronavirus lockdown fatigue.

But Lincoln’s Zoom-town aspirations hit a roadblock last year. It turns out the county doesn’t have sufficient broadband service for its existing population of 27,500, let alone enough to attract newcomers working remotely. A recent survey to find what it needs to improve its infrastructure revealed that residents were so desperate for decent internet they were driving to one of the county’s few McDonald’s to get free Wi-Fi in the parking lot.

“Can you imagine that’s the only way you have access to the internet?” asks Melinda Osterberg, a community development educator at University of Wisconsin-Extension who conducted the survey for the county.

The sense of urgency to close the digital divide in the US has never been greater. The pandemic, by forcing people to work and attend school from home, revealed just how essential broadband has become for households and businesses. And yet, even after accounting for billions of dollars in federal telecom subsidies to expand service, about 42 million Americans, or roughly 13% of the population, can’t access high-speed internet, according to BroadbandNow Research.

About 42 million people, or 13% of the US population, can’t access high-speed internet. Source: BroadbandNow Research

Lawmakers are stepping up with ever bigger spending plans to try to close the gap once and for all. Congressional Democrats unveiled the Accessible, Affordable Internet for All Act in March, seeking to authorize spending more than $94 billion, much of it for high-speed broadband infrastructure in underserved areas. States like Wisconsin, where the governor has declared 2021 the year of broadband access, are also bolstering programs to expand service.

Even President Joseph R. Biden this month proposed spending $100 billion on broadband as part of his American Jobs Plan, aiming for 100% coverage and affordability and saying he would seek to boost competition by supporting more publicly owned networks.

At the same time, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is under pressure to demand more from the industry it regulates. In March, a bipartisan group of four US senators from Colorado, West Virginia, Ohio, and Maine wrote a letter urging the FCC to quadruple the rate it accepts as high-speed broadband from internet service providers; it was last set in 2015. The FCC also moved this year to update and improve the data it uses to determine where the digital divide actually exists.

All Americans will eventually get high-speed internet access because broadband has become endemic to our existence, something the pandemic has only underlined, says Christopher Mitchell, Director of the Community Broadband Networks Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Internet traffic was already growing by double-digit percentages before last year, as streaming video, connected devices, and ownership of tablets, smartphones, and smart TVs soared alongside businesses’ gravitation to cloud-based storage and operations. To allow a chasm in coverage is to ignore how central the internet is to everything now.

“The question is, given how policy is executed, will it be in three years or 12” before that divide is bridged, asks Mitchell.

The longer it takes, the likelier places like Lincoln County get further left behind. The coronavirus has altered US migration patterns, giving professionals the freedom to move to less expensive areas from high-cost cities. The shift is so powerful that it’s created a new class of Zoom towns, communities near popular outdoor destinations with ample broadband to accommodate a surge in remote workers.

Opelika, Alabama, revived its fortunes before the pandemic with fiber optics, according to Nathanael “Phil” Moody, a freelance website and applications designer and developer who joined the Toptal network in 2020. The town of 30,000 people near Auburn University spearheaded a $43 million investment that resulted in a broadband network competing with the area’s telephone and cable incumbents.

The community’s downtown corridor has since been revitalized, says Moody. It has also allowed freelancers like him to thrive because of employers’ expectations of remote workers’ internet.

“Just being able to say I had a fiber connection really went a long way,” says Moody. “People took me a bit more seriously and didn’t see me as a small-time developer.”

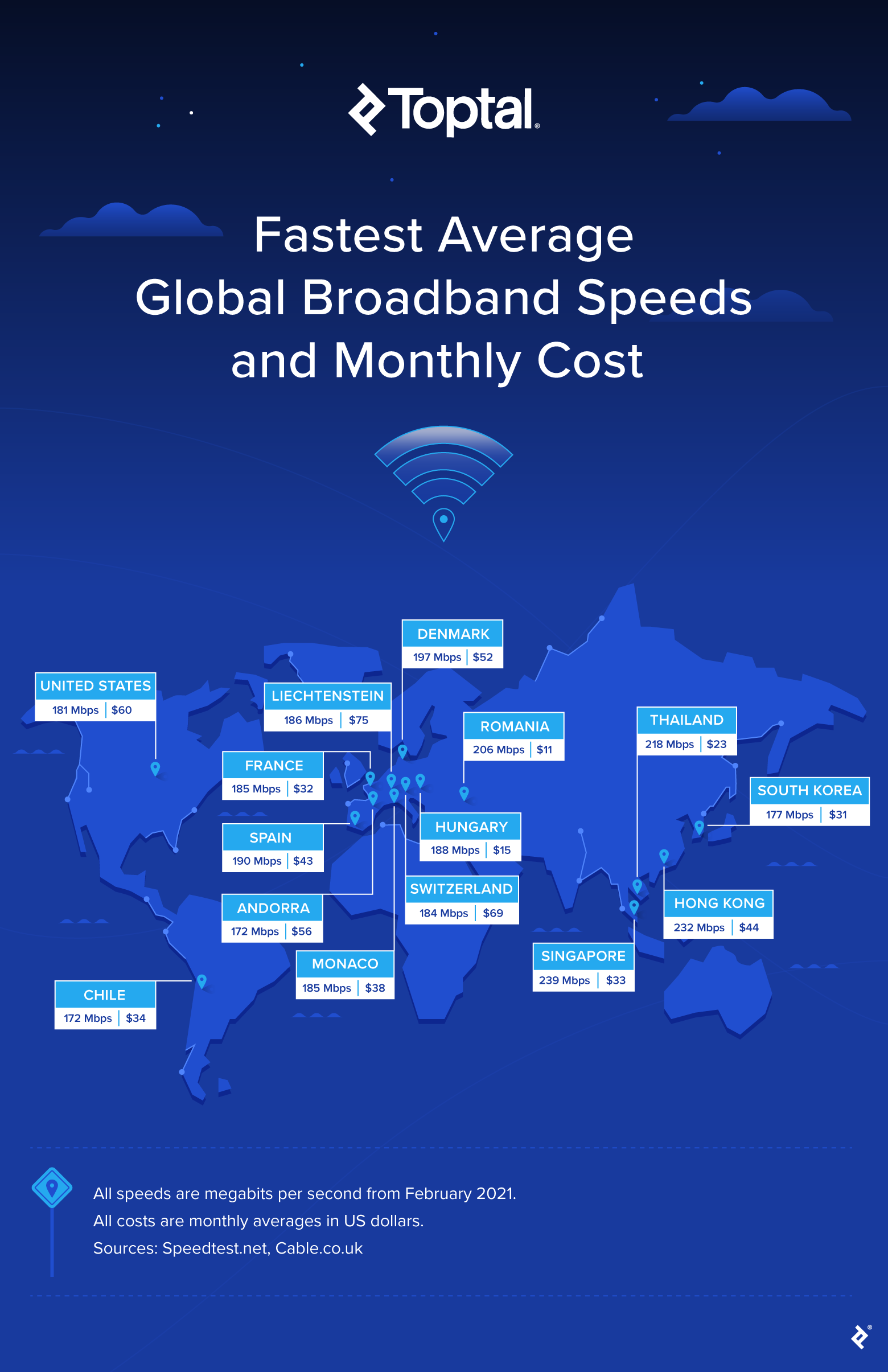

For those who can access it, high-speed networks’ quality in the US is among the world’s best, with prices ranging from moderate to high depending on population density. Download speeds for conventional broadband recently averaged about 180 megabits per second, plenty for multiple devices or users, according to the Speedtest Global Index from network intelligence company Ookla. The average monthly price for digital service in the US was $60 a month last year, the comparison service Cable.co.uk found.

But a digital divide has persisted in part because the upfront cost of laying fiber optic cable, the most robust way to deliver broadband service, has remained relatively steep: estimated to run on average $27,000 a mile. There are alternatives, like fixed wireless, which uses a combination of fiber and towers to transmit data, as well as satellite internet service and 5G cellular networks, but nothing has come along yet that’s cheap and dependable enough to erase the access gap.

The upfront cost of laying fiber optic cable, the most robust way to deliver broadband service, has remained relatively steep: estimated to run on average $27,000 a mile. Source: USTelecom

The FCC was authorized in 2011 to spend about $4.5 billion a year through the Connect America Fund, subsidizing companies like AT&T, as well as local telecom providers, to expand rural high-speed internet access. A significant amount of that money went to upgrading lines for DSL service, which may have seemed adequate when the fund was established, but doesn’t meet today’s demands, says Christopher Fareed Ali, Associate Professor of Media Studies at the University of Virginia.

There are signs of progress, however. The FCC changed its approach to subsidizing rural networks, conducting a competitive bid last year that resulted in awarding $9.2 billion of grants to a much wider cross-section of internet service providers, including Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which has begun to deploy thousands of low-flying satellites above the Earth for a startup called Starlink. The agency says it plans to conduct an additional competition for distributing even more funds over 10 years.

This FCC change is “the most remarkable shift in the telecom industry” since federal telecommunications regulations were overhauled in 1996, says Jonathan Chambers, a former agency official and Co-founder of the company Conexon, which works with rural electric companies building fiber networks. “And it’s happening without anybody really noticing.”

States are also shaking up the competitive landscape by lifting restrictions that had prevented local electric companies from laying fiber to compete with reigning telecom companies. The Ozarks Electric Cooperative has invested about $180 million running fiber over its 7,000-mile electric grid to offer internet, phone, and television services in parts of Arkansas and Oklahoma, a venture that has received about $33 million of funding through FCC programs, a spokeswoman says.

The electric cooperative based in Fayetteville, Arkansas, gained regional fame last year amid the pandemic—by running fiber to school buses in communities its new network had yet to reach, so students could access free Wi-Fi hot spots in school parking lots where they learned remotely.

Lincoln County, Wisconsin, which despite inadequate broadband, has begun to see an increase in new building permits, is taking some inspiration from a neighbor to the south, Marathon County. It has spent years helping communities work with local internet service providers to expand and improve service through state and federal grants, according to Osterberg. Even so, a gap persists there as well.

Whereas making broadband affordable for every household will always present a challenge, growing competition and expanding public support for high-speed investments means it could be just a matter of years before much of the remaining digital divide is finally obsolete in the US, opening up more remote work and economic opportunities in rural areas.

“This is poles, and wires, and conduits,” says Scott Wallsten, President and Senior Fellow at the Technology Policy Institute, a think tank in Washington, DC, that focuses on economic innovation and regulation. “If we spend enough money, you can cover the whole country in fiber.”