Deconstructing Jobs: How Innovative Companies Are Reimagining Work

Boundaries created by traditional jobs are holding businesses back, says Ravin Jesuthasan, author of Work Without Jobs. His case study of Providence Health & Services shows how a new work paradigm can solve talent issues and spur growth.

Boundaries created by traditional jobs are holding businesses back, says Ravin Jesuthasan, author of Work Without Jobs. His case study of Providence Health & Services shows how a new work paradigm can solve talent issues and spur growth.

Kristen Senz

Kristen is Toptal’s Senior Writer for the Future of Work. An experienced journalist and content strategist, her reporting on cutting-edge research and emerging business trends has been published by Forbes, Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, and the World Economic Forum.

Featured Experts

In response to growing skills gaps and rising retirement rates, pioneering business leaders are moving beyond flexible work arrangements to reconsider the very notion of work as a function of jobs and jobholders. As workers continue to jettison full-time jobs to gain more control over their lives, some companies are likewise discovering that the concept of a “job” is restricting organizational agility.

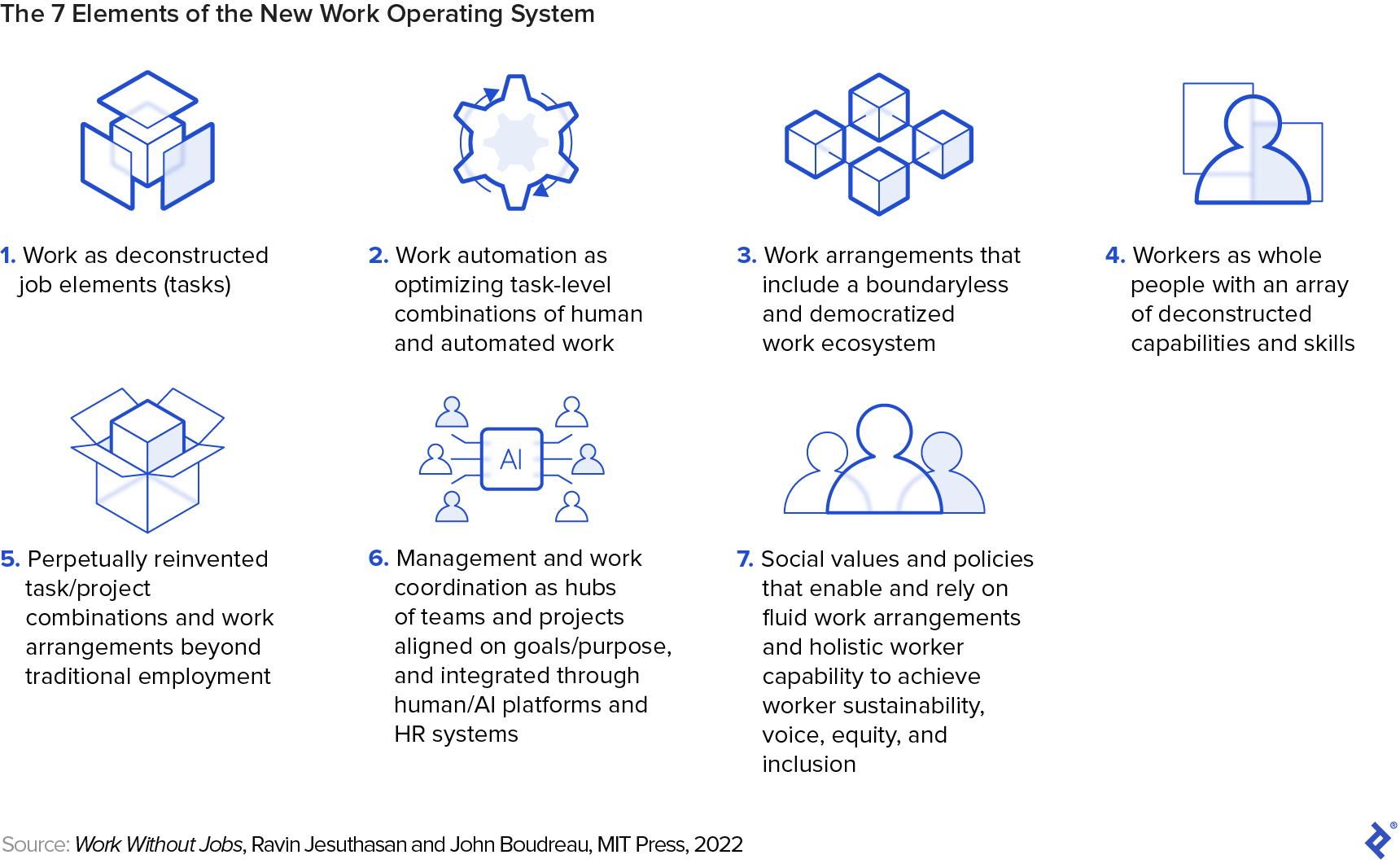

In their new book, Work Without Jobs (March 2022, MIT Press), futurist Ravin Jesuthasan, a Senior Partner and Global Leader for Transformation Services at Mercer, and John Boudreau, a leading researcher on the future of work and Professor Emeritus at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business, suggest that jobs will soon cease to be the primary mechanism for connecting people with work.

In what the authors call “the new work operating system,” managers continuously recombine skills and tasks in ways that are driven by the work itself, rather than by processes and roles. This trend, Jesuthasan tells Toptal, will spur improvements in the use of automation, as well as in online platforms and other digital tools used for engaging internal and external talent. This, in turn, will facilitate a future in which workers apply their skills to various projects “in much more seamless and frictionless ways,” he says.

As more companies adopt this outlook, a new work reality is coming into focus, one based on a system in which workers flow to projects that suit their skills and interests across many organizations.

Transformation at Providence Health

To illustrate this new paradigm, Jesuthasan and Boudreau conducted extensive field research, studying pioneers in transformative talent strategy, including Providence Health & Services.

In 2016, prompted by a worsening national shortage of clinical staff, Providence Health—a 163-year-old nonprofit Catholic health system serving eight states in the western US—embarked on a comprehensive reassessment of how it recruited, allocated, and managed its workforce. This included deconstructing the jobs of clinical staff into individual tasks, noting which ones had to be done by licensed nurses or physicians and which could be done by other workers.

Greg Till, Providence Health’s Executive Vice President and Chief People Officer, says that he and his team first looked for ways to reduce the administrative burden on the clinical workforce.

“Thirty to 40% of a typical nurse or doctor’s job is spent on administrative duties [such as] entering data into our patient medical record,” Till tells Toptal. “In addition to being a poor use of such a valuable clinical resource, administrative work is less engaging to our caregivers. Nurses and doctors want to spend time caring for patients, not interacting with a computer screen or taking notes.”

For example, nurses were spending considerable amounts of time asking patients how they were doing and taking their temperatures, tasks that could be performed by nonclinical staff. Records administrators already knew what had to be entered in a patient’s chart for a status or temperature check “so it was a small change for the same administrator to actually take the temperature or check in on the patient and fill in the chart entry,” Jesuthasan and Boudreau write in Work Without Jobs. In the event that a patient needed assistance or had a high temperature, the administrator would call the nurse.

By deconstructing the nurse’s job, Providence Health freed up substantial time for nurses to do more of the work that required nurse-level training and expertise. As a result of these and other changes championed by Till and his colleagues, clinicians could focus more on diagnosing and treating patients, and in many cases, job satisfaction scores improved.

Providence Health leaders also deconstructed jobs across the company, including in human resources, where they ultimately transitioned to using chatbots and a centralized call center in the Philippines to handle routine employee inquiries. This allowed on-site HR advisors to focus on higher-level work, like planning and strategy.

When presenting these changes to staff, Providence Health leadership framed them in terms of how they would benefit front-line workers. This helped in gaining acceptance, says Till, but implementation wasn’t easy. The corporate office intervening in on-the-ground hospital staffing, for example, was particularly difficult for some local administrators to swallow. “There were, at the early stages, power, resource, and control concerns, like there always are with major changes,” he says. “In several instances, we had to utilize the hospital chief executives and the chief nursing officers across the system to help encourage their peers to get on the bus.”

Pandemic Pressures—and Opportunities

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Providence Health doubled down on these efforts. As the majority of employees transitioned to remote work, clinical staffing shortages worsened, government regulations relaxed, and previous management-related barriers to change eased. These conditions served as what Jesuthasan and Boudreau call a “trigger point,” an opportunity for new experiments in deconstructing jobs and exploring new talent solutions.

First, Providence Health asked each of its 120,000 employees to complete a skills and certifications assessment. In-house capabilities were manually classified and cataloged, a process later embedded in a proprietary digital tool through partnerships with Deloitte and IBM.

“Every one of our hospitals, on a daily basis, went through an exercise where they matched up the skills needed and a predictive model that we had with the skills of the available workforce at those hospitals,” Till says. If they didn’t have what they needed, other staff within the health system were reallocated to perform the work.

Providence Health also expanded its talent sourcing by, for example, asking hospital executives to renew lapsed medical licenses and contribute a few clinical hours each week during COVID surges. Retired staff also returned to help administer vaccines. Additionally, the health system began using machine-learning algorithms to power predictive scheduling for clinical staff, creating opportunities for shorter shifts and removing about 10 hours per week of administrative work for nurse managers.

“These solutions and others have allowed us to increase capacity through the workforce crisis, enabling us to serve more community members and ease the way for our clinicians,” Till says. “They will also reduce administrative costs by more than $100 million over the next 12 months.”

Skills: A New Labor Market Currency

Providence Health leadership focused heavily on skills during the company’s transformation. That emphasis on skills is likewise key to Jesuthasan and Boudreau’s new work operating system, and is rooted in an emerging consensus about the future of work: Employers need new ways to determine fit between workers and work.

“As automation and work converge, skills gaps are set to change at a faster pace and at a greater volume—leading to both talent shortages and job redundancies,” a 2019 World Economic Forum report by Jesuthasan and colleagues stated. “Companies face a pressing need for innovative talent sourcing, matching, and development strategies.”

The World Economic Forum, where Jesuthasan sits on the Steering Committee on Work and Employment, argues that the traditional system of evaluating job candidates based on factors such as educational degrees, the brand of an educational institution or employer, or social connections is largely inefficient and perpetuates socioeconomic inequalities. Instead, the WEF advocates a new system based on workers’ track records of proven skills and consistent upskilling.

Transitioning Away From Traditional HR Practices

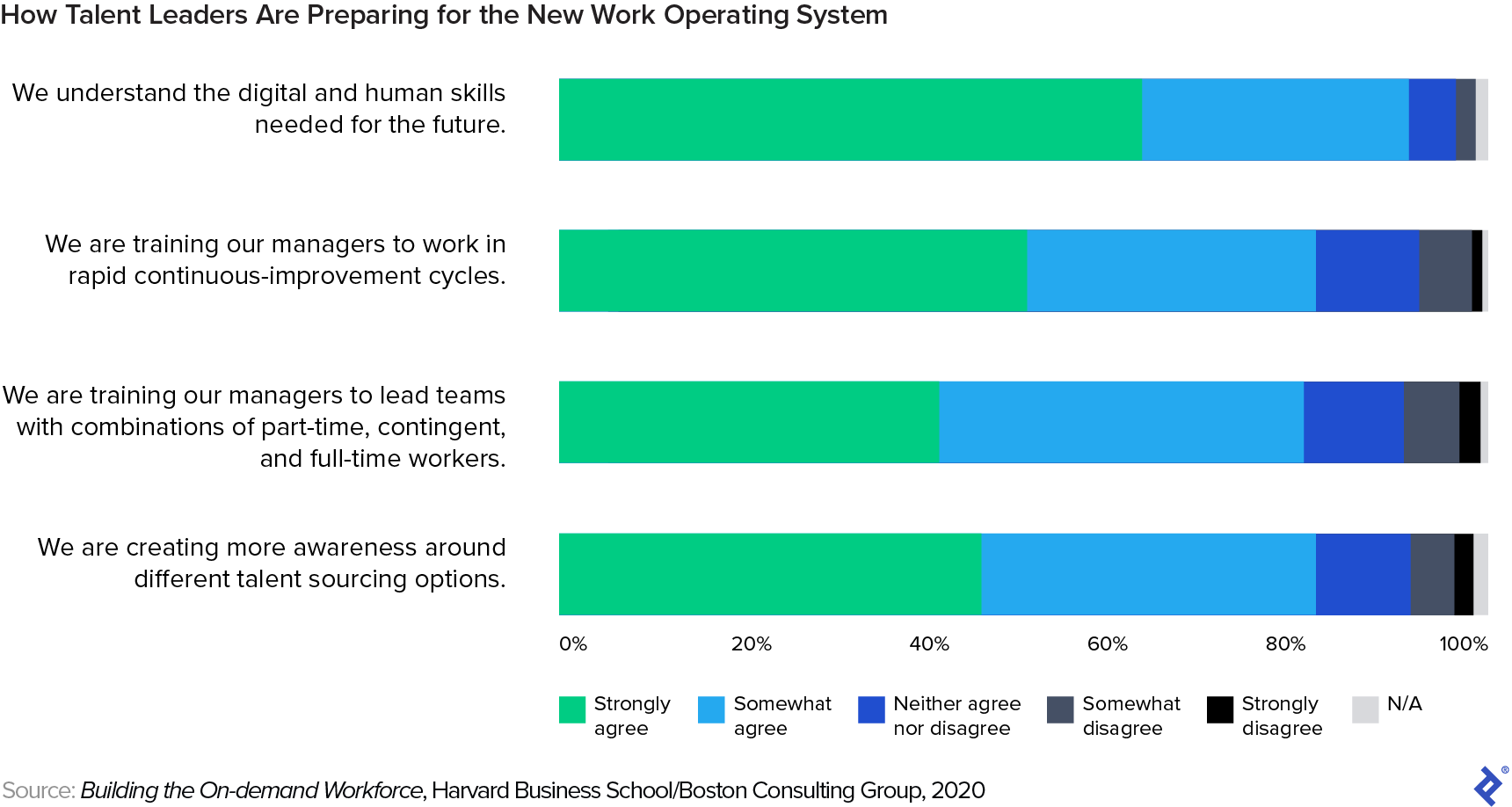

Even among business leaders who recognize the need for this type of sea change, strategies that shift the focus away from traditional HR practices—recruiting, hiring, training, and retaining workers to occupy conventional jobs—remain daunting. Often, when work can’t be delegated to an existing staff member, the simplest solution for managers is to request a new hire, says Jesuthasan. Slowly, however, this is changing.

“Many companies are trying to break managers from that immediate reaction and say, ‘Hey, we’re going to equip you to be thoughtful and knowledgeable in deconstructing the job, understanding the work, and then figuring out what makes the most sense,’” he says.

Sometimes, it makes sense to bring in freelancers or consultants to fill a particular skill gap rather than adding to the workload of an existing employee. As talent shortages become more acute, many companies are engaging contingent workers for short- and long-term assignments, on which they either work independently or on teams with employees.

According to a November 2020 report on in-demand workforce trends, nearly 50% of the 700 US business leaders surveyed said they expect their use of online talent platforms to increase significantly in the future.

Problems can arise, however, when companies take vacant staff jobs and fill them with contractors in order to save money, says Matthew Bidwell, an associate professor of management at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Bidwell has studied how companies use contractors in the field of information technology. He found that managers typically turn to contractors for one of two broad reasons: either they have a short-term need and lack the in-house skills, or they have headcount constraints but a budget to pay freelance help.

“My impression is that a vast amount of the use of contractors is in that second category,” Bidwell tells Toptal Insights. “And that leads to all sorts of complications.”

Because freelancers generally lack context and institutional knowledge, parsing projects that they can do effectively can be difficult and lead to wasted investments, he says.

The Evolving Talent Economy

Jesuthasan and Boudreau don’t contend that workers will cease to work full-time for a single employer, only that such engagements will decline over time. Instead, they argue that by first deconstructing jobs, organizations can more easily separate tasks and projects that gig workers or freelance talent can do without lengthy on-ramps. They suggest creating strong relationships with talent platforms and looking for ways to provide or amplify a reward structure through such networks, to help build strong ties with both long-term and occasional-but-repeat contributors.

Unlike the early gig economy, which was highly transactional, the emerging talent economy centers on projects and teams in which leaders lead through influence, trust, and negotiation, rather than through the authority conferred by organizational charts. Relationships, Jesuthasan says, are the foundation of the new work operating system.

“Now, nothing is purely transactional,” he says. “Everything is kind of a relationship. My network is the single most important thing, right? The relationships I have. And that’s what I think more and more companies are starting to realize.”