As Talent Goes Remote, Smaller Cities Make Big Gains

San Francisco and New York City are not the draws they once were because of a surge in virtual work options. Now, surprising new hubs are emerging.

San Francisco and New York City are not the draws they once were because of a surge in virtual work options. Now, surprising new hubs are emerging.

Michael J. McDonald

Michael J. McDonald is an award-winning journalist who has worked for Bloomberg News and Thomson Financial. He is a Senior Writer at Toptal.

Kate Valdes never really thought about relocating from the San Francisco Bay Area to Sacramento, the sleepy California capital 90 minutes inland. All that changed last year.

Valdes, a member of the Toptal network since 2019, was searching for a house to buy near San Francisco with her new husband. When they were both forced to work from home indefinitely starting in March, their search expanded to less expensive areas, ultimately stretching all the way to Sacramento. That’s where they found the ideal single-family home and unwittingly joined an exodus spurred by COVID-19 that could transform American cities’ future.

“It’s been really amazing,” says Valdes, a product designer who once worked for Netflix in Silicon Valley but now works remotely for Charlotte, North Carolina-based Discovery Education. “As soon as we started getting to know our neighbors, we knew it was home.”

In the decade prior to the pandemic, major urban centers like San Francisco and New York dominated the US economy, generating the lion’s share of innovation and job growth while serving as magnets for the country’s and world’s top talent. Not even advances in technology that enabled more remote work could dent that dominance.

That reality shifted last year as shutdowns were imposed to limit the virus’s spread. The biggest, most expensive cities saw the sharpest declines in rents as crime rates surged and residents fled, a migration made possible as employers found most computer-based office duties could be done as productively from home.

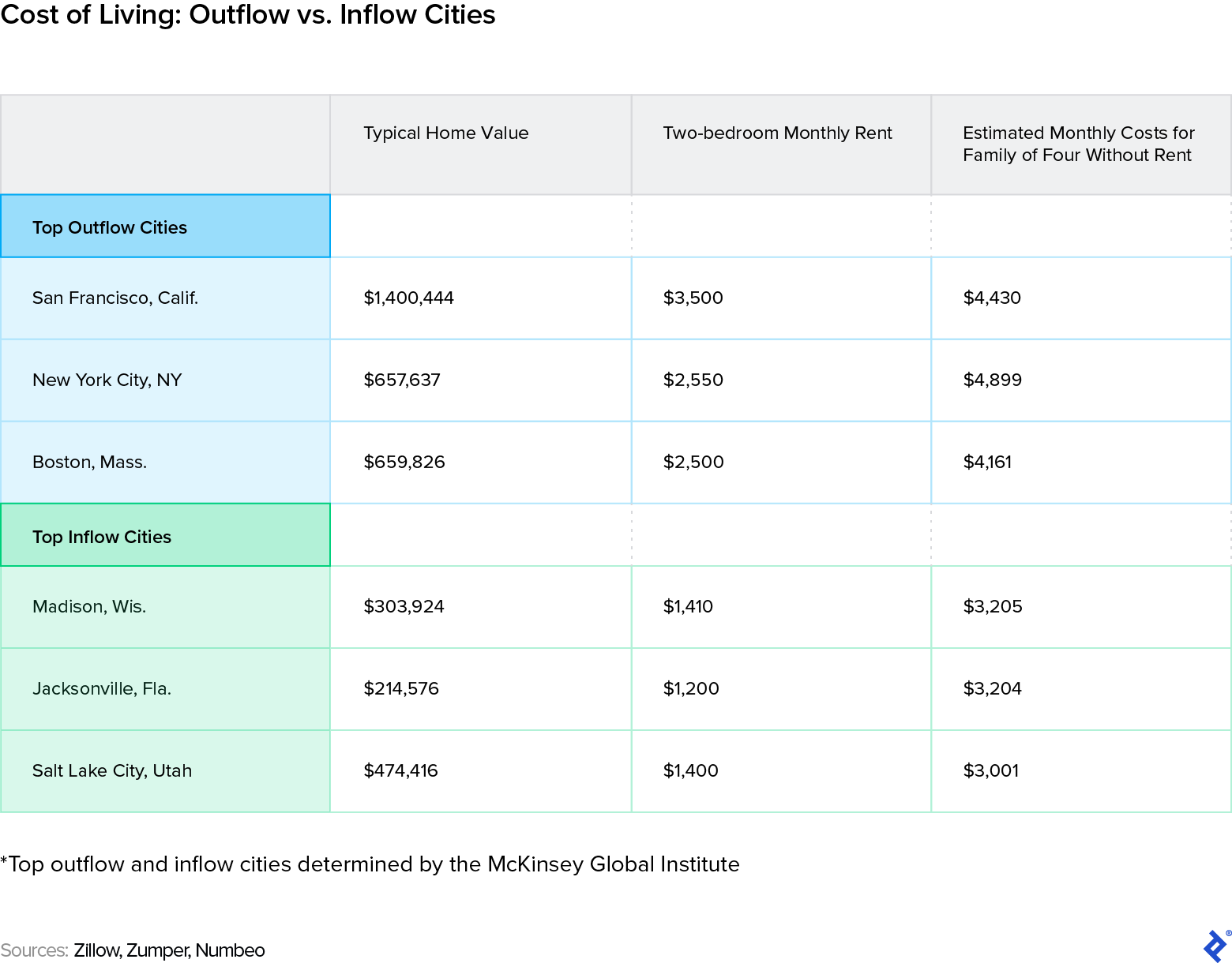

So, where did they go? Smaller, more affordable cities, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company. Using location data from LinkedIn, the consulting firm revealed that Madison, Wisconsin, for instance, saw the inflow of workers increase 10% relative to outflows from April through October 2020, compared with the same period in 2019. In Jacksonville, Florida, the inflow-outflow ratio was up 9%, and for Salt Lake City and Sacramento, 5%.

By contrast, the ratio of workers moving to New York City versus people departing was -27%, while San Francisco similarly plummeted, at -24%, McKinsey shared in the report, “The Future of Work After COVID-19,” released last month. In Boston, the ratio was -13% and Los Angeles, -11%.

The outflows point to a new paradigm for urban economies, says Erik Stettler, Toptal’s Chief Economist. The virus has vanquished cultural barriers that prevented remote work in the past, triggering a structural shift in where work gets done. Opportunities are no longer strictly location based, and so, smaller hubs can be more competitive, he says.

“Cities will need to adapt to the new reality,” Stettler says. “They are now competing for the best talent, rather than the world’s best talent competing for access to certain key financial and tech hubs.”

Takuma Kakehi, a Toptal network designer, had only recently relocated to Manhattan’s Upper East Side from Brooklyn, after having his first child, when his wife, rattled by safety and space concerns, insisted it was time to leave New York. The family relocated in September to Baltimore, near where his wife was raised, renting an apartment twice the size of their Manhattan walk-up—and in the historic Fells Point neighborhood on the city’s redeveloped waterfront.

“Until we made the move, there was that stress,” says Kakehi, who is also Head of Design in the US for Japanese SaaS company Uzabase Inc.

Michael Harris also left New York City but for a home in Canton, Ohio, after leaving his dream job at a Manhattan hedge fund just before the pandemic arrived. He wanted to be closer to his family and remove himself from the bustle and density of New York.

Harris bought a dog, a pickup truck, and a duplex home in an old Canton neighborhood called Harter Heights that’s known for its red brick roads. Now he’s engaged to be married and planning to relocate again, this time an hour’s drive north to Cleveland. His career focus: as a freelancer in the Toptal network developing apps for clients.

Cleveland saw a 2% increase in inflow of workers versus outflows last year, according to McKinsey, while Kansas City, Missouri, another town that’s been reinventing itself, saw a 1% gain. “This is pretty country,” says Jeff Bryant, a UX designer who left his full-time job in Chicago to relocate his family to where he was raised in the Kansas City suburbs.

Some communities are trying to take advantage of the shift. Tulsa, Oklahoma, for instance, has gone so far as to offer cash incentives for remote workers willing to relocate there. Other so-called Zoom towns are just trying to manage an unexpected influx—locales like Sandpoint, Idaho, that are near sprawling public parks or ski areas have seen population growth strain local resources.

With jobs you can do remotely, “you can live just about anywhere if you have good friends and supportive family,” says Joshua Berman, a branding and design expert who moved to Tulsa from Washington, DC, before the lockdowns, buying a house that he says would have cost five times as much in the nation’s capital.

Because of the lower cost of living, particularly for housing, and the often improved quality of life, much of the talent that has moved from large urban centers likely isn’t going to return. This is another factor forcing companies to develop the technological infrastructure and organizational culture to facilitate remote and hybrid work, say experts like Stettler.

Companies that adjust to the new geography of work will not only improve their cost structure by reducing the need for real estate, but also they will put themselves at a competitive advantage in attracting and retaining the more mobile highly skilled workers.

“What we’re confronting now is a powerful change,” says Stettler. “There will be winners and losers.”