Everything You Need to Know About UX Sketching

UX sketching is a crucial, yet often overlooked, aspect of UX design. It’s a very efficient way of communicating design while allowing designers to iterate multiple ideas before settling on one.

UX sketching is a crucial, yet often overlooked, aspect of UX design. It’s a very efficient way of communicating design while allowing designers to iterate multiple ideas before settling on one.

Nick is a senior UI/UX designer with eight years of experience designing applications for the fast-paced and demanding startup world.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

If you’ve done any sort of serious creative work, you are all too familiar with creative block. It feels like hitting a brick wall: None of the ideas you’re able to visualize are good enough, or can’t work in real life.

For designers, the feeling is all too familiar. However, like any complicated problem with no clear solution, a smart process can make all the differences. This is where UX sketching comes in.

UX sketching is a crucial, yet often overlooked, aspect of user experience design. Sketching is a very efficient way of communicating design while allowing designers to try out a multitude of ideas and iterate them before settling on one.

In this UX design sketch tutorial, I intend to cover everything you need to know about sketching in UX design, including the following points:

- Introduction to UX sketches and wireframes

- UX sketching basics, tools, and techniques

- Clarifying sketches with notes, annotations, numbers

- UX sketching tips and tricks

- Mini-methods designed to boost quality and productivity

- All you need to know about Wireflows

- A quick guide to UX flow sketching

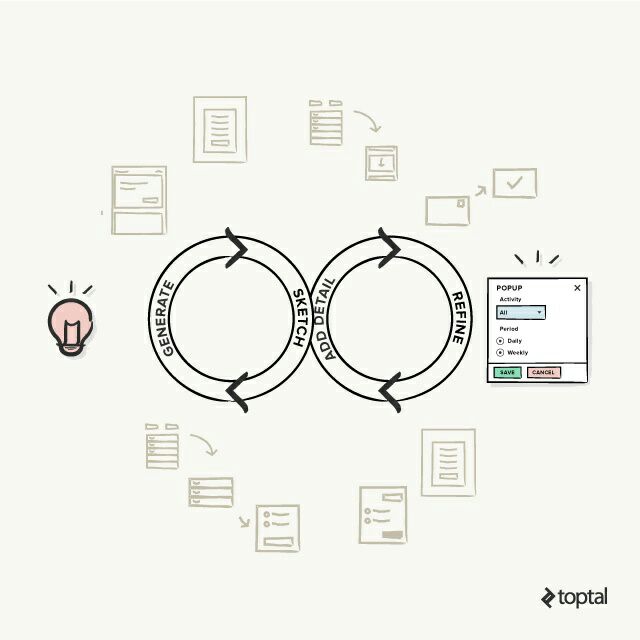

UX Design Sketching Is a Two-step Process

Many options must be considered in design, which results in the choice and the execution of the best one. Designers consider their options, and then proceed to work out the details, thus making UX design a two-step process:

- Idea Generation

In the initial step, multiple ideas are generated, but since they cannot be fully shaped, it is not uncommon for some of the elements to be incomplete or missing. The main thing is to consider different approaches and to decide which is the most efficient in the context of your task and the various constraints of the project.

- Adding Detail and Refinement

Step by step, you settle on a few promising variants and proceed to work out the specifics, thus rendering some ideas unsuitable.

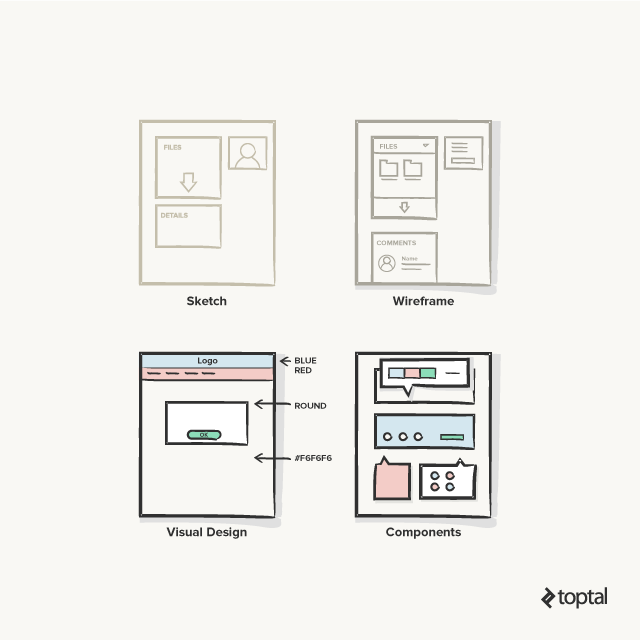

UX Sketches and Wireframes: Introduction and Classification

Your wireframes may differ depending on factors such as the desired level of detail, colors and style, whether you are going to show them to someone, and so on.

I singled out the following sketch types:

- Sketch: Idea Generation

These are initial sketches. Lower-level details are simply noted. A limited number of colors is employed.

I draw a lot of basic sketches to consider the problem from different angles and to consider different solutions. While drawing such sketches, I am also striving to generate as many solution variants as possible.

At this particular step, incompleteness frees my mind, which is why it is so important to avoid getting bogged down in minutiae at this stage. My goal is to generate as many ideas as possible and choose the most promising ones.

- Wireframe: Specification, Detailed Phase

I usually pick promising sketches and go over the details, after which I choose the best variant and work it out in greater detail.

However, this does not mean every single detail. Obvious things may just be noted. Moreover, some aspects will be difficult to describe on paper.

At this step, I draw all the important details, but I do not yet draw wireframes in Balsamiq. After everything is done on the paper, I start drawing in Sketch.

Digital tools provide a lot more creative freedom than paper and you can easily shift attention to minor things. For example, you can focus on “pixel polishing” instead of design.

- Visual Design Draft

This is a rarely used approach, but sometimes it can be helpful. Various visual solutions are considered at an early stage of the project, but it may take a long time to create digital sketches for all of them. That is why I draw design sketches on paper first, to consider different options and choose a visual design direction.

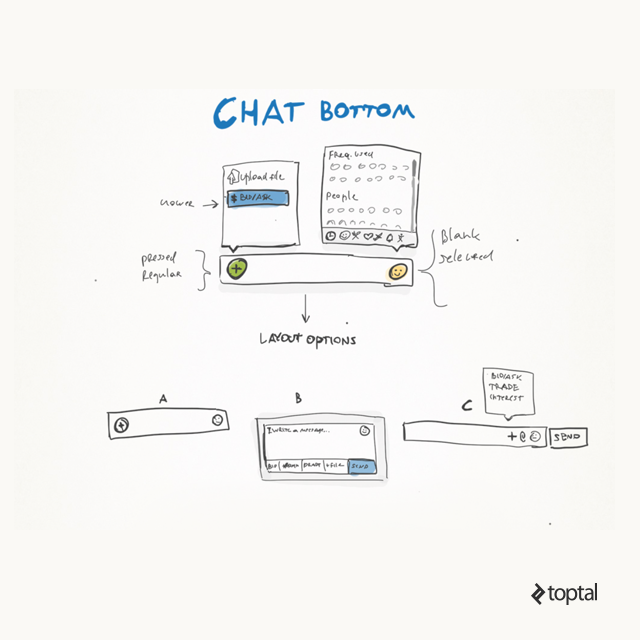

- Components/Elements Breakdown

I find this technique useful when I already have a general idea and I am thinking about a particular page functionality or of the integral parts of interface components. I draw different page elements, going into detail, and then draw different possible positions of the page elements.

Elements, even the most simple ones, must have a state; a button can be pressed and it has a hover text block that may or may not be empty. The more complex it is, the more states it has.

Getting Started with the Basics

- Prepare your UX sketching tools. Find the most convenient place possible, a large table with plenty of space. Take a lot of paper and prepare some pens and markers.

- Warm up. In order to get ready, I recommend drawing some lines, circles, basic templates, and icons.

- Define your goals. Decide what you want to draw. Set your aim and decide what story you have to tell. Determine the desired level of detailing. Decide whether you are ready to draw a lot.

- Define your target audience. If you are doing this for yourself, you don’t need to worry about the way your sketch looks. However, if you intend to show your drawings to a client, make sure you allow some extra time to add more details to your sketch.

- Set a time frame. Having decided on the amount of time you are ready to allocate for sketching, let’s say 30 minutes, will help you focus on your work.

Now, you are all set and you can get started:

-

Draw the edges. Draw the frames, a browser or phone window, a part of the interface, and so on.

-

Add the biggest or basic elements: menu, footer, main content.

-

Add details. Add relevant details, but keep them simple at this stage.

-

Add annotations and notes. These are required only if you’re planning to share the sketches. However, they can be useful even if you’re doing them for your eyes only.

-

Sketch alternatives. Sketch some quick alternatives to your solution.

-

Pick the best solution. Choose the best options.

-

Add shadow and bevel. This is particularly important for sharing purposes. Add a shadow to make your sketch visually appealing, which is important if you plan to share it with team members and/or clients.

-

Save the sketch. Take a photo or put it in a folder. I have a few paper trays on my table for sketches.

-

Share. I usually use one of the following sharing methods:

- Scan sketches via Evernote and provide a permalink to other team members or stakeholders.

- Take a photo and upload to InVision.

- Upload and map images to Realtimeboard.

- Or just email a photo.

- Review the sketches and add notes. Take a break and then come back to your sketches a while later. Take a look at them again. Does the sketch still make sense to you? A good sketch must be easy to follow.

Clarifying Sketches with Additional Elements

Find or draw a proper sketch, and then add the following details to it:

-

Title. Sometimes, adding a title is a good option. Write a description and date, if necessary, at the top of the sketch. The title will help you understand what you are looking at and whether or not the sketch is relevant. This is especially useful if you have a lot of sketches or you are going to show to others.

-

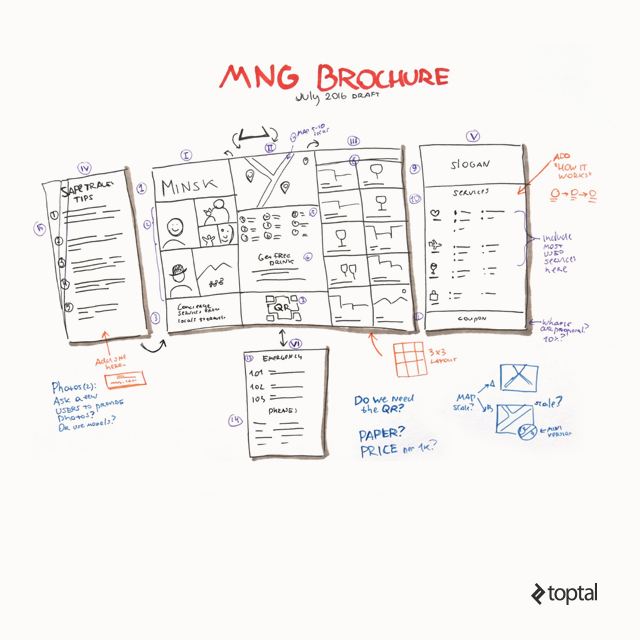

Annotations. Annotations are names and notes placed close to an element, to explain its content or other attributes. They add details that clarify other elements and are usually difficult to draw. For example, it could be the name of the block, some interaction details, an explanation of a picture, some ideas for future design variations, and so on. You can check out one of my UX sketch examples to see what an annotation sketch looks like.

-

Numbers. Number the elements of your sketch, or the sketches themselves. You can decide how to order them (e.g., by interaction flow, the order in which you created them, etc.). It may also be useful during discussions (especially remote discussions), as your colleagues and clients can just point out the sketch number in their feedback and you will understand which one their comments refer to.

-

Arrows. You can use arrows to indicate screen transitions. They can also be used to connect different parts of sketches, to indicate a sequence of actions, and so on. Since the meaning of an arrow can vary, just above the arrow you can add a description or explanation of what the arrow is meant to signify. Here is an example of a basic sketch showing a transition and several different states.

-

Notes. Just like annotations, notes are used to explain concepts. However, notes differ from annotations in their placement. They are not attached to an element or located near the described element, similar to this example. Notes can be placed at the top or bottom of the page. They can even describe elements that are not included in the design, questions that you may have, general explanations, unsketched ideas, and so on.

-

Gestures. Gestures are relevant in the case of touch device design. Drawing a hand gesture may require practice. There are several variants of gestures used to indicate different types of actions, so it is better to decide in advance how you designate a particular action (if it is not obvious, of course) and to practice drawing it.

-

Feedback. You may receive suggestions for fixing or improving the sketch after showing it to others, or after you take another look at it yourself. It is often useful to mark such feedback in a different color so as to help differentiate feedback from the original sketch.

You can use different colors for different types of elements. Sometimes, I use black for drawings, blue for links, dark green for notes, red for titles and feedback. Try to use different colors in your sketches, but make sure your choice of colors is consistent!

More Specific Tips and Tricks

-

Don’t worry about the quality. Don’t look at the sketches on Dribbble; they are about something completely different. Bear in mind that the main purpose of sketches is to help you think more clearly, find better solutions, and save time.

-

Practice. For a start, you can try to draw a few apps. Open a web or mobile app and try to copy the screen, describing the elements in the notes. Whenever you have some free time, practice drawing basic building blocks of your designs. In general, practice makes perfect. In a while, it will become part of your designer self.

-

Buy a folder. I often don’t work from my office, but rather from a cafe or my home. Paper sketches are very prone to damage, so buy a simple folder to keep them safe and sound.

-

Bring tools with you wherever you go. This helps ensure that you can capture your idea on paper at any time, otherwise you may just lose the thought or not be able to remember it in sufficient detail. I always have a notepad, a few A4 sheets, and pens with me.

-

Share with others. It’s very important to engage other people and communicate with your team. Involving others and getting their feedback, especially early on, helps save time and resources in the long run. You can also encourage others to draw the way they envision the design.

-

Paper trays. Think of placing paper trays on your worktable. For example, I have three of them: for incoming tasks, for sketches, and clean sheets of paper.

-

Experiment and customize. My recommendations are based on my experience. In time, you’ll find out what suits you best; which methods, which sequence of steps, what exactly fulfills your creative potential. You will get there only if you constantly try something new, which is why it’s important to experiment with different formats, styles, and try new templates.

-

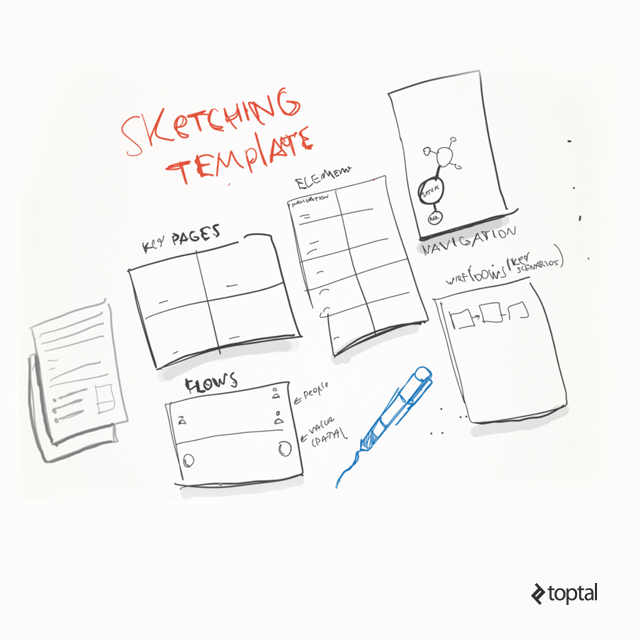

Use templates. Templates will save time and implicitly take into account format restrictions, freeing up more time to focus on what is important.

Additional Mini-methods to Improve Your Sketches

These aren’t necessarily tips and tricks, but they’re a collection of methods, tools, and suggestions that should boost your productivity or improve the quality of your sketches.

-

Create a sketch board. One of the biggest benefits of using pen and paper instead of a digital sketching tool is that you can actually stick it to a wall. Everyone on your team can see it and participate (although I recommend setting up review sessions).

- You will see your sketches yourself, and this will stimulate your thinking and let you see the big picture, not isolated pieces, but the whole system. You will see interactions between parts and the way they fit one another.

- Create the sketch board - attach your whiteboard sketches. If there is no whiteboard in your office, you can use double-sized adhesive tape or post-it note sheets to stick your sketches to the wall. If you don’t want to stick to the wall, you can find a big piece of cardboard paper instead. I strongly recommend using sketch boards, as they’re one of the best design tools.

- You will see your sketches yourself, and this will stimulate your thinking and let you see the big picture, not isolated pieces, but the whole system. You will see interactions between parts and the way they fit one another.

-

Use a whiteboard. A whiteboard is a great drawing tool. It has a number of advantages:

- It is collaborative, and it is easy to involve other team members in the discussion and in the drawing as well. Even if their ideas do not fit well, you will understand their way of thinking, and it will help you to be on the same page.

- Markers do not let you focus on details, you have to think about the general things. Sketches are open to interpretation.

- A whiteboard is easy to clean and make corrections on.

- There is a lot of space and you can easily think through the whole system flow.

- You can attach sketches, printouts, and reference materials using magnets.

- It is collaborative, and it is easy to involve other team members in the discussion and in the drawing as well. Even if their ideas do not fit well, you will understand their way of thinking, and it will help you to be on the same page.

-

Prototypes. Make a clickable prototype to evaluate your design. Try to get feedback about some elements. This works particularly well when you are using templates - your sketches are of the same size. Obviously, it will be much easier to draw same size sketches if you are using a template. I will try to make it even easier by providing you with a few templates you can download and use: Mobile, Browser multi-window, Browser scroll, Personas.

-

Use your printer and scanner. Draw the framework by hand (you can use ruler to draw more accurately), then just scan it using a scanner or mobile app, and print it. You can edit your template in image redactor before printing. You can remove unnecessary details or duplicate some elements. You can also print a readymade site page, photos, and other descriptive elements. You can paste the cut-outs in your sketch.

-

Use Evernote for scanning. Evernote is a great design tool. You can keep and share your sketches in it, you can create themes, and use tags to organize your sketches. The abilities of the “Scanner” mode are particularly impressive. You put your sketch in front of it and it “scans” it, so you get the copy of the sketch. Then you can invite your colleagues to Evernote and give them your note link. Since there is a mobile app for tablets and phones, you can always have your sketches at hand.

-

Hybrid sketching. To put some life and realism into your sketches you can combine them with photos. That means that you have to take a photo and then draw some story with interface elements on it. This can also help you to notice some interaction issues and details.

- Tracing real world. If you need to create a storyboard, illustrate an experience in a specific context (e.g., a person using a smartphone at a bus station), you need to include depictions of people, places, and various real-life objects. These can be difficult to draw, especially if you haven’t mastered drawing skills, but here’s a simple tip: Take a photo of the object or the situation, and then obtain the key objects contour using an image editor. You can use the resulting contour in your sketches afterward. Of course, if you have a tablet and stylus, it will be even easier.

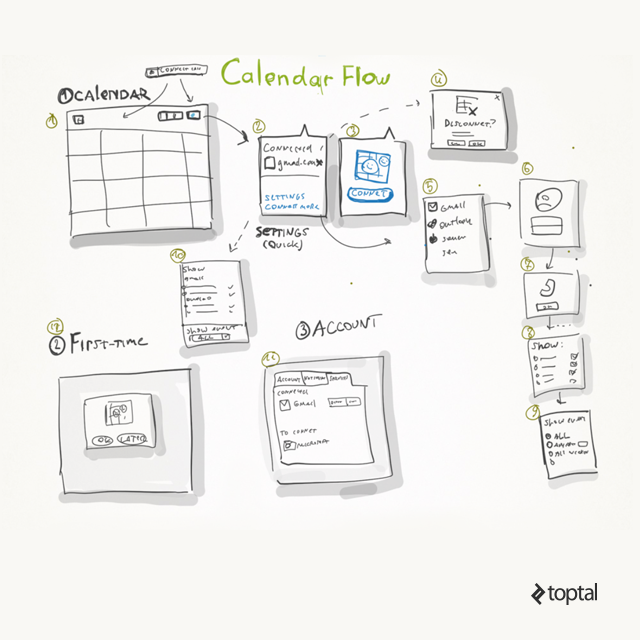

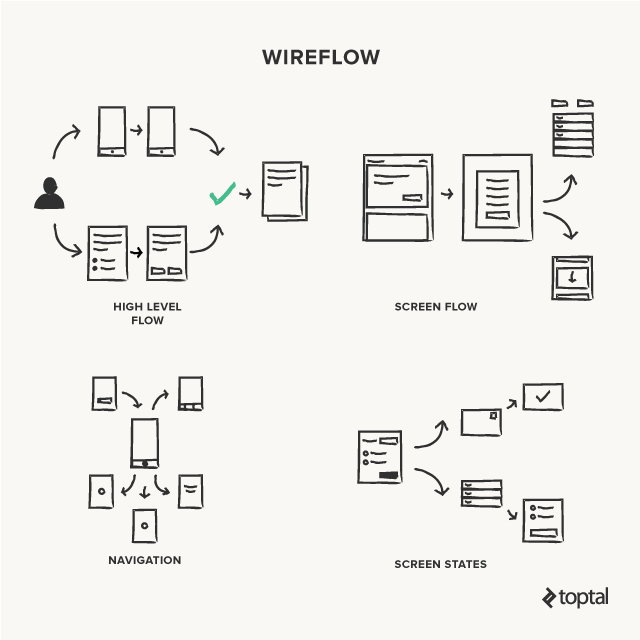

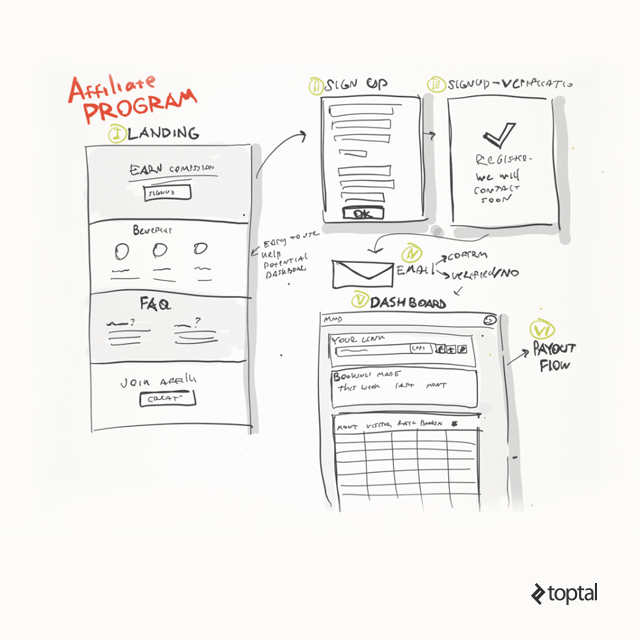

Wireflow: Outlining System Flow and Branching

The wireflow is essentially a sequence of the system flow, screen after screen, with branches and decision points. We should consider how a user addresses their task, the way they move from screen to screen, and their overall experience of the product over time.

Wireflow, or what you are drawing and the way it is connected, could be organized according to the following approaches:

- Sequence. A sequence is a straight journey, screen after screen. It can also be a story with decision points; you show not only the journey but also decision points and different paths the user can choose. You can show the structure of screen interaction.

- State changes. Depict different screen states of some element and the conditions or actions that cause the transitions between these states.

- Screen vs. screen elements. You can draw the whole screens or consider micro-interactions and interactions.

- Platforms. You can consider one platform experience or multiple platforms.

- Scope. Will you depict a part of the user journey or the whole journey? One user interaction with the system, or multiple users’ interactions?

I generally try to define the following wireflow types, depending on the organization and practical use:

-

Mapping overall flow and high-level flow. Promptly sketch the screen shifts and draw the general journey of your product usage. Here you can include some context and you can optionally show some user interaction. For example, an eCommerce shopping service is quite a long journey that may include a lot of steps: how the user found the shop, the steps they went through to order the product, how they paid, and so on.

-

Screen flow. This focuses on a specific functional flow through the system. It could be a small straight sequence of screens or a journey with branching. For example, a user uploading some photos or a video.

-

Navigation scheme. Draw your screen and the options it contains. This is not supposed to map the journey. This step includes information that shows the options a user can choose, the directions users have, and various app parts. I usually create a navigation scheme at the beginning of a project. It serves to understand how navigation should be structured (what points should be included, how many levels are necessary).

-

Screen states. Draw the screen or element states (an example might be a file upload dialogue). In this case, for example, the screen will have the following states:

- Blank

- A user pulls the file in the active area

- The file is uploading

- The file is uploaded

- There is an error

Sketching UX Flow: A Quick How-to Guide

The wireflow design process is similar to the wireframe one. Many steps are similar or identical, but there are some important differences:

Define what you need to draw. Decide exactly what you want to draw (e.g., the general history or a fragment of your design). Do you want to generate different options or to think through the details of one journey? Decide whether you are going to show your sketches to someone else or not.

Define what keyframes and transitions you should include in your drawing. If you add all the screens and shifts your wireflow will be very long and complex. Consider which key screens you should show to convey the essence of the interaction that helps accomplish your task. The same goes for screen shifts. You need to choose which shifts will be more useful in expressing your idea. Check out this example for reference.

Define the starting point. What will be the starting point of your journey? You can start with the entry point, i.e., the start of the journey, for example, what a user sees when they log into your app. Alternatively, you can start at the midpoint or with the most interesting/difficult/important screens or process steps. Or you can start at the end, with the end result achieved by a user, and describe the steps the user took to come to this point.

Decide what comes next. After drawing the starting steps, decide what goes next by answering the following questions:

- Which way does this step lead users?

- Which way do you want them to go?

- What do they have to do to get there?

Sketch alternative routes, entries. Think about alternative ways the user can get to each step:

- What will happen if the user’s Internet connection fails?

- What other options do they have?

- What can go wrong in the case of user or app error, what will happen?

- What will happen if the user closes the app at this step?

- Where will the user start the next time he launches the app?

Think about alternative flows. Analyze the history, design an alternative flow, and sketch it.

Add annotations, notes, details. Add the explanatory elements that will clarify non-obvious details.

Save. Make a digital copy of the sketch.

Share. Share the sketch (e.g., via Evernote or InVision).

Essential UX Flow Sketching Tips and Tricks

Draft a wireflow first. If you are going to think quite a long journey over, you would better make a quick sketch in order to understand how much space you need and in order not to miss some important steps or details. It would be difficult to add them to the paper sketch afterward.

Don’t create a huge map with too many details. Paper sketches don’t have an undo button, so it will be difficult to make changes. You may draw the details too accurately and this will distract your imagination from the generation of different high-level variants. Instead of creating a huge scheme that would illustrate the entire system, try to focus on the key scripts and try to dedicate an individual page for each script.

Cut unnecessary details and combine various detalization levels. It is not necessary to draw all the interaction descriptions, so try to use only the key elements of your journey. While drawing a huge interactions map, you have no need to work every single screen out in detail. Some screens could be just represented by several squares, and other, key screens, could be worked out in detail.

Try different paper sizes. Try different paper formats, A3 or A5. Paper sheet size will limit you and will affect your process in different ways. A small paper sheet will not let you add many screens or details, but it can help you to concentrate on the main ideas. Using a big paper sheet, you can draw one huge journey, a lot of details, and additional notes. Alternatively, you can place a number of small journeys on it.

Post-it notes can help too. You can also try to use post-it notes. You can draw separate screens or some footnotes on them, or you can draw additional states of your sketch’s elements. Their advantage is that they can be easily replaced, you can also simply move the note somewhere else. For example, in case the flow has changed, you can just change the order of your post-it notes.

Use templates. Try to use templates. They will save time and will enable you to create more clickable, high-quality prototypes.

Try using a whiteboard. A whiteboard has a number of advantages. It is becoming more and more popular because it allows you to draw a huge journey with a lot of branches. You can draw a lot of application components on paper and then just attach them to the whiteboard using magnets, adding them to the journey.

Sketching a shadow. Shadows can help you to mark important elements and they add visual attractiveness to your sketch. I use three different types of shadows:

- Lines following the light direction - this does not always look beautiful, but you can use the graduation and pick the objects up to different “heights.”

- Outlining some part out with a darker color (only the bottom or the bottom and right side)

- Using the Pro-marker (or its equivalent in the app you use for drawing)

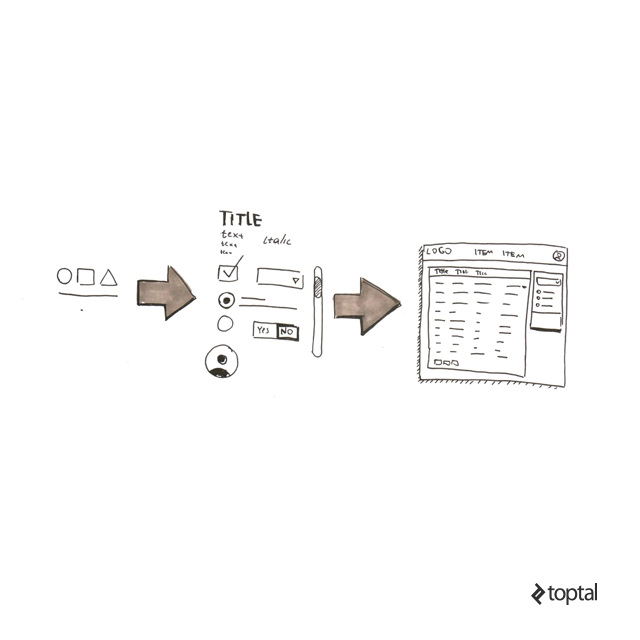

Drawing components. An objection like “I can’t draw that well” may stifle your initiative. It is actually easier than it sounds. Even the most complex sketches are generally composed of a number of basic blocks, like in this example. If you can draw a point, a line, a triangle, a square, and a circle, then you have the essential building blocks you need to draw anything for your sketch.

Putting it all together. The basic elements, buttons, radio buttons, and dropdowns are composed of basic elements. After learning to draw these elements, you can combine them and draw complex blocks and components.

Wrap Up

The goal of this post was not to create the ultimate, one-size-fits-all guide to UX sketching, or sketching in general, because designers have different needs and personal preferences.

As you can see, this is a lot to cover. Designers use a myriad of tools, techniques, and approaches to produce UX sketches, and it’s rather subjective. Certain techniques may or may not work for different people working on different projects. If you’re just getting started, you should definitely experiment. Constant practice and experimentation will help you find what works for you.

It’s up to you to choose tips and techniques that will be the best fit for your project and your approach to design. Do you have any additional sketching tips for fellow UXers? Feel free to share them in the comment section.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- E-commerce UX: An Overview of Best Practices (with Infographic)

- Heuristic Principles for Mobile Interfaces

- The Best UX Designer Portfolios: Inspiring Case Studies and Examples

- The Importance of Human-centered Design in Product Design

- Anticipatory Design: How to Create Magical User Experiences

- Play Is the Point: How UX Designers Can Break Into the Gaming Industry

- 6 Ways to Make Authentication Systems More User-friendly

Nick Vyhouski

Toronto, ON, Canada

Member since February 8, 2016

About the author

Nick is a senior UI/UX designer with eight years of experience designing applications for the fast-paced and demanding startup world.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT