Sharpen Your Skills: The Value of Multidisciplinary Design

Want to become a phenomenal designer? Take a multidisciplinary design approach and study the methods of other design disciplines.

Want to become a phenomenal designer? Take a multidisciplinary design approach and study the methods of other design disciplines.

Peter has four years of professional experience in digital interface design, typography, and graphic design with a user-centered approach.

Design Is a Universal Endeavor

Design is everywhere; it’s all around us. We design our environments, our food, our virtual spaces, and even our bodies. Design is a critical form of human interaction.

Whether shopping for a table, deciding on a dinner menu, or choosing a shirt for a date, our everyday decisions involve design. Professionally speaking, we use the word design to describe the process of shaping how humans interact with objects, experiences, and environments. Designers must consider aesthetic, functional, economic, and sociopolitical aspects of both design objects and the design process. This involves considerable research, thought, modeling, and redesign.

Since all design work is rooted in a familiar language, practicing one discipline increases aptitude in another. Herein lies the value of a multidisciplinary design background. Growth in a specific discipline simultaneously boosts overall design intuition.

Concerning aesthetics, design is closely related to fine art. However, design’s ultimate goal is to provide a certain function, interaction, and usability within the boundaries of a curated experience. Design fundamentally converts the interaction experience into an emotion.

It’s also worth noting that geography and culture significantly affect design. The people, customs, beliefs, and locations existing in the designed world undeniably influence the designers which inhabit it. Ideally, designers of various disciplines would work together without conflict to form a single curated experience.

Design Has a Common Language

There are common and corresponding design elements that help designers understand foreign disciplines while deepening knowledge of familiar ones. Design elements like layout, contrast, and pattern are present in all design fields and serve as the tools designers use to emphasize aspects of their work.

For instance, if a graphic designer understands shape, line, and scale for print, their knowledge will not disappear if they transition to UI design. Instead, their comprehension will cross over and aid them as they learn how to apply those same elements for digital outcomes.

Additionally, the design process allows designers from different backgrounds to collaborate through research, ideation, prototyping, redesign, and concept presentation. Let’s investigate this further.

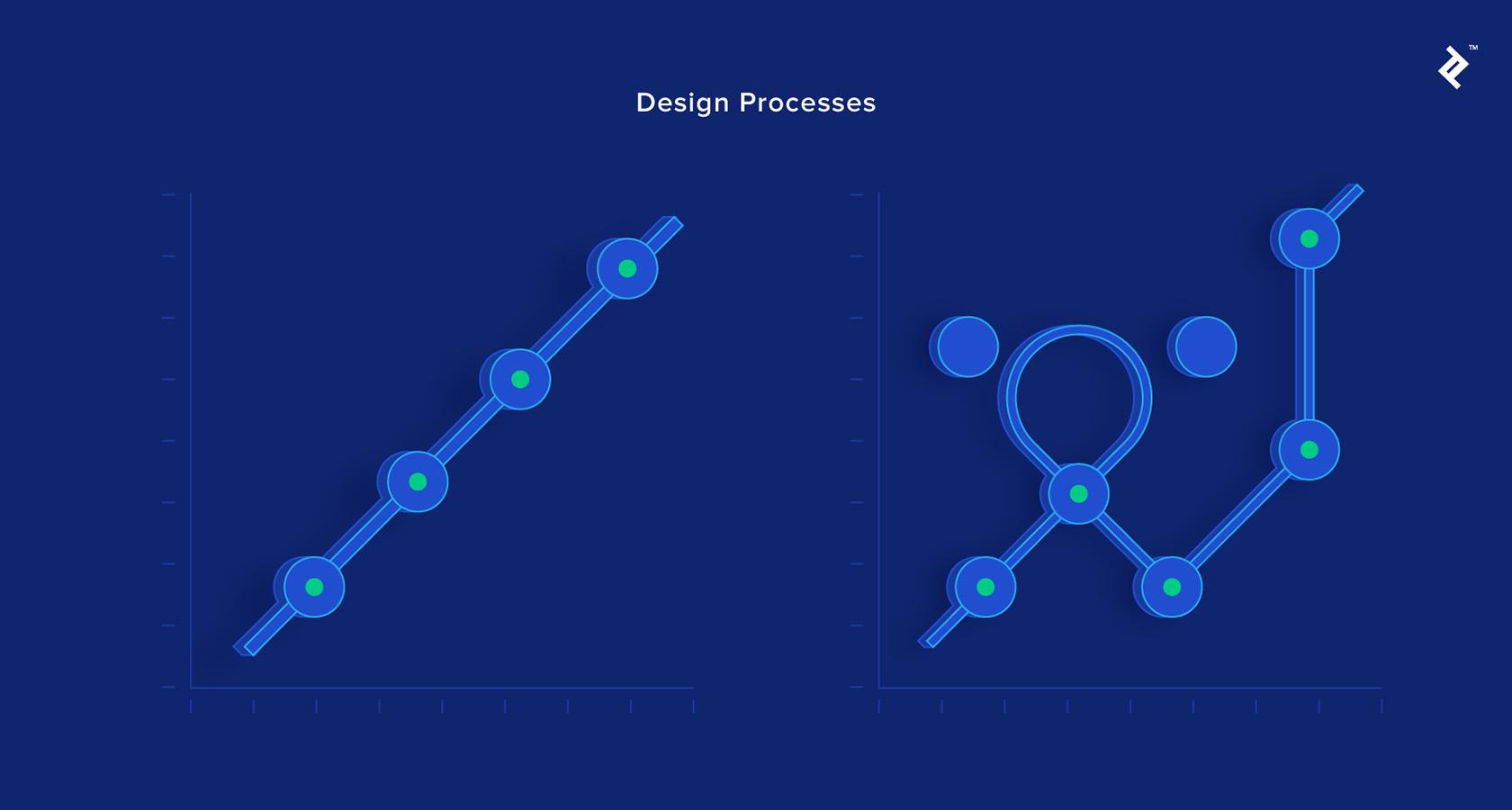

The Design Process: Rational vs. Evolutionary Models

There is much disagreement about what the ideal design process looks like. Kees Dorst and Judith Dijkhuis believe that “there are many ways of describing design processes,” so they outlined “two basic and fundamentally different ways”—the rational model and the evolutionary model. Although these models have their differences, their main goal is to define the process of design. In this way, they work together and serve as a valuable bridge between design disciplines.

The Rational Model

The rational model views the design process as a plan-driven, sequential progress through distinct stages. Here, design is informed by research and knowledge in a controlled manner. The stages are pre-production design, design during production, post-production design, and redesign. Each stage consists of several smaller processes.

The problem with this model is that most designers don’t work this way. Goals, budgets, and resources are prone to change. Design rarely flows from one anticipated step to the next. Problems arise and course corrections must be made—sometimes the process jumps ahead, and other times it starts over.

Although rarely used, this method acts as a base for many other processes throughout the design disciplines. The waterfall model, systems development life cycle, and much of engineering design literature are by-products of the rational model.

The Evolutionary Model

The evolutionary model is a more spontaneous approach consisting of multiple interrelated concepts. It posits that design is improvised without a defined sequence of stages—different stages of the process (analysis, design, and implementation) are all concurrent.

In the evolutionary model, designers use creativity and emotion to generate design possibilities. This model also sees design as informed by research and knowledge (just as the rational model), but these are brought into the design process through the judgment and common sense of the designer.

Since this method is not hard-coded in terms of stage order, it is present in almost all of the disciplines. This is our contemporary design paradigm, and once mastered, it can be widely applied, making it the cornerstone of exploring new fields.

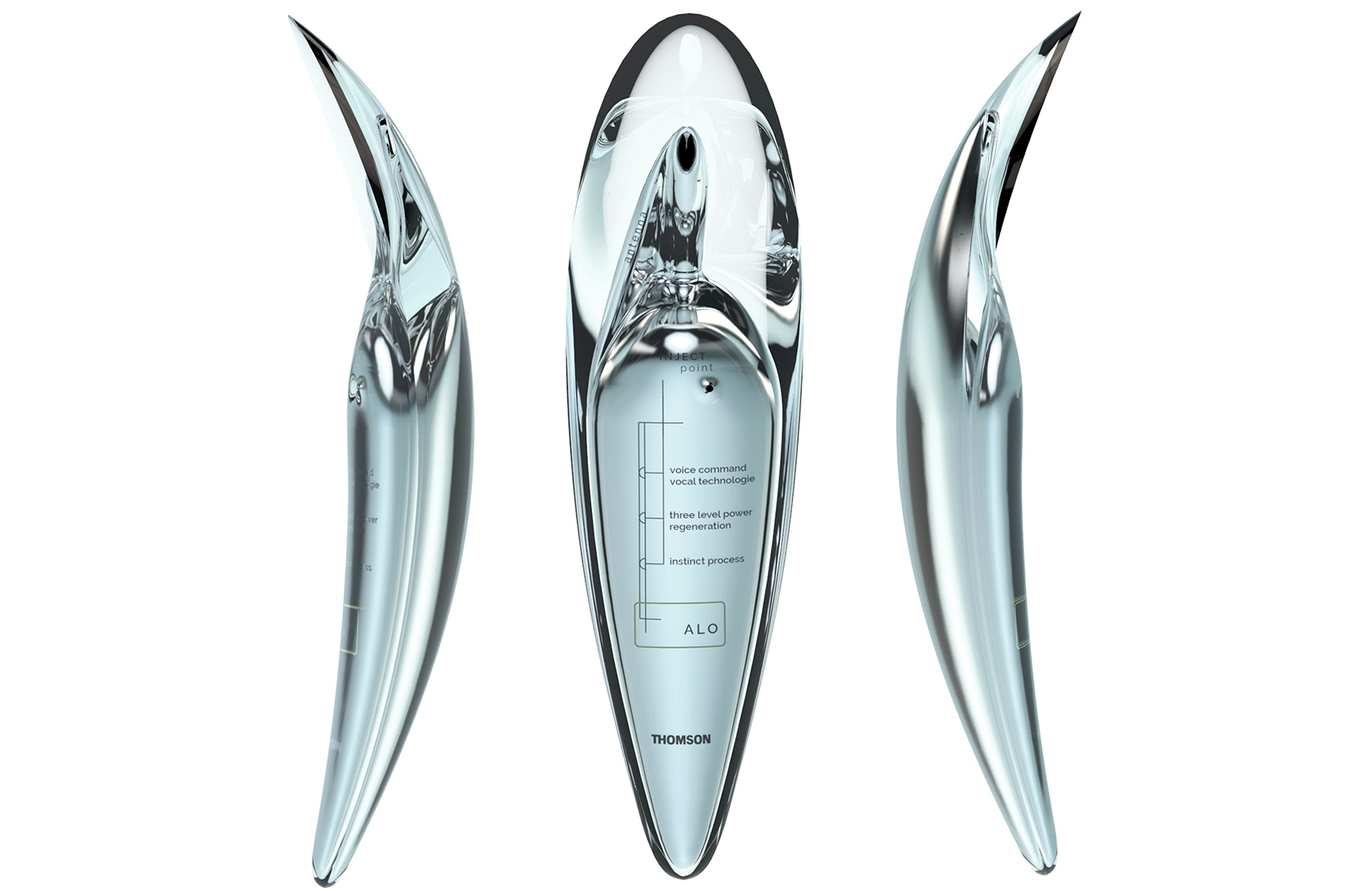

Abstraction Is Thoughtful Reduction

Abstraction is a handy tool for every designer. To make something less in detail, volume, or complexity while communicating the same message requires practice, but it is a crucial skill for designers of today’s user interfaces and experiences. It’s also useful when designing logos, illustrations, icons, color palettes, and type schemes. As Ludwig Mies van der Rohe once said: “Less is more.”

A great way to begin the process of abstraction is to strip your brief of its written objective. How does this work?

Think of a product designer who is briefed to design a new pair of rain boots. If they begin sketching with the intent of designing new rain boots, their pencil will likely produce a mishmash of solutions and styles already stored in their mind.

However, if they change the brief to read “Create two waterproof objects that protect feet and keep socks dry” they are more likely to access untested inventions and forms in the first round of concept sketching. Many of these initial sketches will be wild and nonsensical, but within the whimsy, they may find new and exciting design possibilities that can be refined over additional rounds of sketching. The famous French designer Philippe Starck often works in this way.

Holistic Design Respects Every Detail

With any design project, it’s critical that designers respect the amount of time required to fully develop all details. In this regard, design is like a machine—all the parts must be in working order and functioning as a whole for the system to operate properly. Holistic design does not allow designers to ignore tedious tasks or unglamourous product features.

In architecture, even the tiniest of design mistakes can have a fatal outcome. A miscalculated steel value in a reinforced concrete structure or failure to understand how building materials age over time can ruin the whole design. The same goes for other fields of design. Not all design mistakes are as catastrophic as a collapsing building, but they can still implode a brand or business. How?

Consider a brand that changes logos, colors, and illustration styles every few quarters. Perhaps this company has no clear brand strategy, and all design decisions are based on current trends as opposed to research or a strong concept. The result would be utter confusion among the brand’s intended audience. “What does this company stand for? What are they trying to say? Is this a brand I can trust?”

Good designers consider all the details. In the case of branding, things like company history, target audience, and messaging cannot be overlooked. Mies van der Rohe also said, “God is in the details.” Essentially, designers should strive for perfection in every task. No exceptions.

Design Research Provides Meaningful Context

When we create new things or think of new concepts, there’s a chance that someone else has covered the same ground before us. Looking for and finding these examples can help our decision-making process while learning from others’ mistakes can also be helpful.

Design research is a time to bring context to a project. No design project exists in a vacuum. Societal, environmental, and economic considerations abound. Just because something can be achieved doesn’t mean that it’s a worthwhile undertaking. Research is the time to investigate questions and concerns that might not be in a brief but are sure to surface once a project begins.

It’s important to note that there are different styles of research within the design disciplines. The research of a UX designer specializing in healthcare tools will look drastically different than that of an art director working on fashion brands. Even so, the intent of research across disciplines is quite similar: Understand the problem, glean insight from past solutions, and plan a path forward.

Articulate Design Choices Persuasively

A design that is equal parts beautiful, functional, and thoughtful doesn’t always guarantee success. How one presents design concepts is just as important.

Oftentimes, inexperienced designers fail to develop presentation abilities. Most of their time is spent honing technical skills and polishing the fine details of their projects. Conceptual intent exists in their work, but they don’t think of ways to articulate the design choices they make.

Unfortunately, this can lead to frustrating breakdowns with clients who don’t have design training and need to be guided through the evolution of a concept.

If presentation is a new avenue for you as a designer, be encouraged. A world of possibility awaits as you learn how to serve up design concepts in an appetizing way. Thankfully, many of the skills you need are skills you already have.

Typography, color choice, image selection, and page layout are key aspects of visual storytelling. Additionally, many of the big questions that drive your design decisions—the whys, hows, and whats—provide the exact information that clients want to understand. Keep things clear and simple. A capable designer with strong presentation skills is a force to be reckoned with.

There’s No Need to Practice Every Design Discipline

Understanding different disciplines doesn’t mean that a designer needs to practice them all. Comprehension of how other disciplines work and the rules they employ can be just as good. When designing a mobile interface, for instance, designers should be aware of mobile design principles and best practices of both device and platform, yet they don’t need past product design experience to achieve a beautiful or functional UI.

It might even be said that practicing too many design disciplines could be a professional hindrance. How so? Consider a UI designer who also works in branding, photography, and animation. These disciplines are interrelated and tie together in successful interface designs, but a designer who tries to juggle them all risks creative tunnel vision and burnout. Better to investigate broadly, understand deeply, and practice narrowly.

Designers Must Go Beyond Predictable Boundaries

Design thinking is ancient and innately linked to human consciousness. As we explore and experience the surrounding world, we seek to invent new ways to work, play, and live in relation to one another. With design, we aim to improve our homes, our schools, and our planet. The problems are numerous, and their complexity is great. There are few quick fixes.

Edith Widder once said that “Exploration is the engine that drives innovation.” As designers, we benefit our careers (and future clients) when we dare to venture beyond the boundaries of our own disciplines. Learning about different methods, tools, and skills helps broaden our internal problem-solving libraries and provides us with deeper decision-making context. For instance, UI designers who understand the key principles of brand messaging are able to embody brand tone and mood in the interfaces they create.

Being a designer means being able to push past obvious answers in order to create solutions that enhance the human experience, and this starts with a keen understanding of the connections between design disciplines.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is meant by a design methodology?

Design methodology is the process that designers use to find the best solution to a problem. Depending on a designer’s discipline and the problem being worked on, different types of design methodology may be employed. Common components of design methodology are research, brainstorming, and user testing.

What is the first stage of the design process?

The first stage of the design process is defining the problem. Before a solution can be found, designers must know what the problem is. If the problem is poorly defined, every other step of the design process is likely to encounter major obstacles.

What is a multidisciplinary approach?

A multidisciplinary design approach seeks to integrate the skills and methodology of designers from multiple disciplines into a collaborative effort. Multidisciplinary designers need to understand how diverse areas of expertise can come together to solve complex design problems.

Budapest, Hungary

Member since February 8, 2016

About the author

Peter has four years of professional experience in digital interface design, typography, and graphic design with a user-centered approach.