3 Cybersecurity Archetypes and How They Affect Risk Priorities and Staffing

Is your organization an Operator, a Builder, or a Governor? Toptal’s Information Security Practice Lead, Michael Figueroa, reveals how this knowledge helps CISOs fine-tune their security teams and tactics.

Is your organization an Operator, a Builder, or a Governor? Toptal’s Information Security Practice Lead, Michael Figueroa, reveals how this knowledge helps CISOs fine-tune their security teams and tactics.

Michael is the Information Security Practice Lead at Toptal. He holds a bachelor’s degree in brain and cognitive sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a master’s degree in high-tech crime investigations from George Washington University. Before joining Toptal, Michael served as executive director of the Advanced Cyber Security Center, and held other roles in the field, including consultant, principal investigator, advisor to government officials, and chief information security officer.

PREVIOUSLY AT

When I was a security executive for a late-stage startup in the early days of fintech, a peer told me the three-envelope parable for the first time. Its origin is not entirely clear (this 1982 Washington Post opinion piece opens with a two letter Soviet-era version), but the tale is commonly adapted to many different leadership roles. For a chief information security officer (CISO), it reads something like this:

A new CISO walks into their office for the first time and finds three envelopes on the desk. They’re labeled 1 to 3, and with them is a brief note from their predecessor:

“Congratulations on the new role! I am sure that you are going to do great. But, if something goes wrong and you are forced to respond to a major security incident or data breach, open the next envelope in the series for guidance.”

During the first incident, the CISO opens the first envelope to find the advice,

“Blame your predecessor.”

After the second incident, the CISO opens the second envelope, which says,

“Blame your budget.”

In the third envelope is another three-word note,

“Prepare three letters.”

The cruel reality is that many CISOs reach the third-envelope stage after as little as 18 months in their role. The exception may be CISOs managing security programs with significant resources, such as Fortune 500 companies, who seem to retain their roles far longer. But it would be a mistake to assume that longevity is only due to larger budgets. Most CISOs, regardless of the relative depth of their pockets, don’t think they have sufficient resources for a truly effective security program.

In my experience working with security executives at organizations of just about every size, I’ve learned that the most consistent key to success isn’t budget, it’s understanding your company’s security “personality”—and identifying the critical supporting roles and practices needed to complement that archetype.

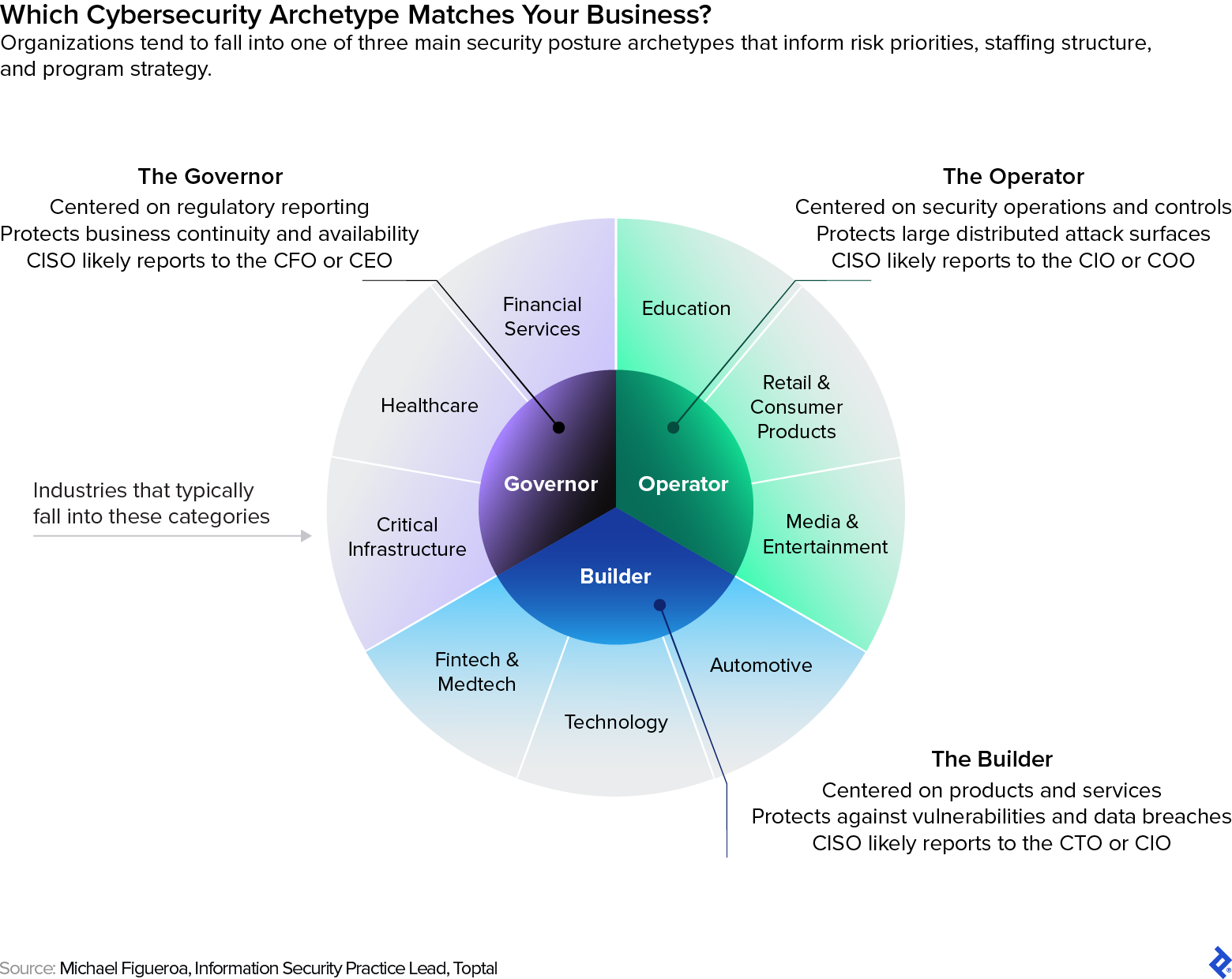

During my 27 years as a security professional, and in my role as the Information Security Practice Lead at Toptal, I have found that most organizations fall into one of three security archetypes:

-

The Operator: Probably the most dominant type, this personality describes metrics-driven organizations that are most concerned about deploying effective security operations center (SOC) capabilities and monitoring how security controls are implemented, managed, and maintained for effectiveness.

- Operators tend to be larger organizations with a lot of moving parts and large leadership teams that distribute risk management accountability and act on performance dashboards to assess business-aligned security risks and report on mitigation actions.

- A CISO in this type of organization may report directly to the CEO (especially in critical infrastructure domains), but is more likely to report to the COO or chief information officer (CIO).

-

The Builder: Organizations that build products, run online applications, and provide managed services tend to focus most on product security management.

- Builders are most concerned with developing tightly coupled security capabilities, maintaining a continuous view of how security controls need to adapt to a changing threat landscape, and mitigating potential exploitation of weaknesses through proactive vulnerability assessment and workforce upskilling.

- In organizations of this type, the CISO usually reports to the chief technology officer (CTO) or CIO.

-

The Governor: Banks, healthcare companies, and other organizations that operate under stringent regulatory oversight must focus most of their attention on security governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) efforts to structure and formalize business processes for responding to independent authorities.

- Governor organizations’ success depends on monitoring the organizational adherence to security policies, assessing how business and financial risks are impacted by potential and realized security incidents, and developing regular formal reports to specific authorities.

- In these types of organizations, the CISO usually reports to the chief financial officer (CFO) or CEO with strong board-level visibility.

No matter their background or experience, a CISO has a better chance of succeeding if they understand their organization’s personality, and then build a program to match that personality by aligning on risk posture, building an archetype-appropriate team, and engaging strategic third party partners.

Toptal Case Study

One recent client I worked with was a technology company that serves customers in a highly regulated industry. As such, their new CISO built a program aligned with a Governor security personality, focused on GRC. While that security posture matched this company’s customers, it didn’t match the company itself. And, despite an impressive background and a solid security plan, conflicts arose which resulted in the CISO’s exit (and a protracted, six-month search for a replacement). I helped the company leaders realize that, instead of hiring another GRC-focused CISO, they needed to source someone who was able to align with the true Builder archetype of their own organization—someone who would develop security programs and react to risk priorities that better supported their business.

Priority 1: Align With the Organization’s Risk Posture

It is easy for a CISO to pull out an industry-standard security framework like ISO 27001 or NIST Cybersecurity Framework and measure the maturity of an organization’s security program against each security control. Indeed, addressing every control is important for maintaining a healthy and sound information security program. However, conducting such an exercise without accounting for the organization’s risk appetite threatens unnecessary friction between the security program and business leaders.

A more helpful exercise is to assess a given standard framework’s components against the organization’s security personality to determine which controls are most important, and which fall too far outside of recognized business risks to warrant significant investment. That organizational context will ultimately provide a constructive foundation for building consensus around security needs.

For example, in a previous role where I managed advanced technology development for a government-funded research laboratory, I had to enable a cloud-based collaborative work environment accessible to both our internal scientists and a global cohort of academics. That Builder-aligned need was, on its face, a direct violation of the strict governance posture that an organization heavily involved in national defense would seemingly have to take on.

Rather than attempt to enforce strict security governance controls that would constrain our engagement with foreign collaborators, the CISO and I established a segmented infrastructure environment that would support the operational needs of the project while compensating for the lost security controls in other Governor-aligned ways. Doing otherwise would have simply driven the team to bypass the governance regime entirely and defeat absolutely necessary protections.

In this instance, the CISO and I—a former CISO myself—were able to collaborate and come up with a solution. Too often, however, CISO’s are somewhat on their own, without similarly knowledgeable counterparts able to help them see the big picture. In those instances, an independent security program design strategist can help identify potential points of friction and solutions to those blockers.

Priority 2: Nurture an Archetype-aligned Security Team

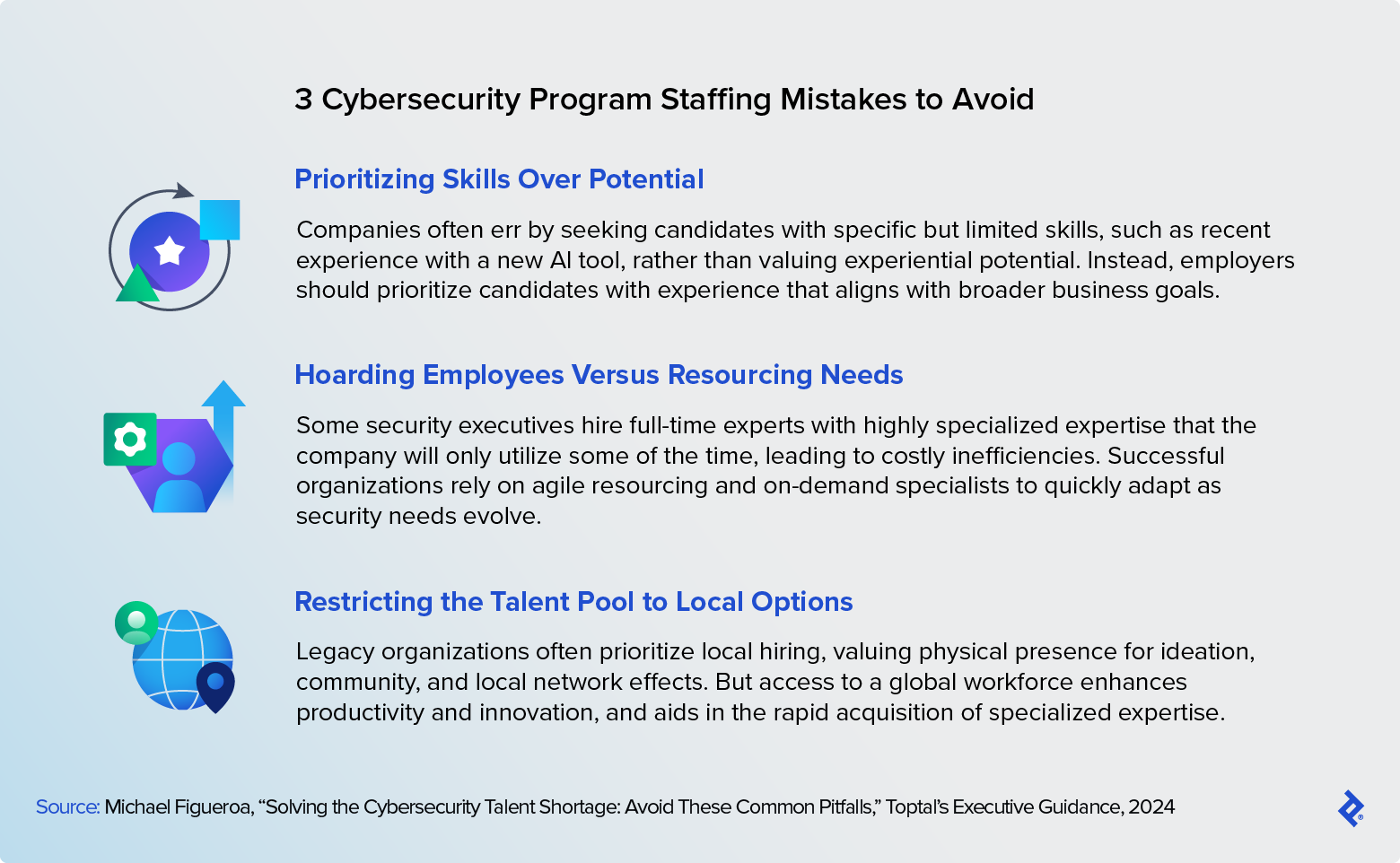

An effective security executive must consider their organization’s security personality to optimally align staffing resources to critical business needs. To do this well, they must often first overcome their own expertise biases. For example, in my experience, companies tend to prioritize hiring candidates with direct industry experience over those with experiential potential and archetype alignment. Though direct experience may certainly be valuable, artificially restricting the talent pool can also reinforce inefficient industry-wide legacy practices and prevent the introduction of helpful personality-aligned cross-industry innovations.

Toptal Case Study

When one global industrial products manufacturer came to me struggling to identify security analysts to help manage a compliance exercise, I noted that they were focusing too much on skills, and ignoring their cybersecurity personality. Because industrial manufacturers often face stiff regulatory pressures, the company was seeking security GRC professionals. But the company itself was more closely aligned with the Builder personality, so I suggested a change in strategy. The company began looking for analysts in the product development space and quickly engaged with an executive product security analyst who had an impressive healthtech background. That independent professional became a trusted advisor to the client, taking over the coordination of multiple compliance efforts in just a matter of a few months.

Priority 3: Engage With Strategic Third-party Partners

Operating in a dynamic threat environment with persistently evolving adversaries, security executives never have enough budget to protect against every conceivable attack vector. Similarly, they never have the resources to fully cover all the security controls needed to defend their companies from attack.

To be most efficient in their use of limited resources, CISOs should build their team structure around a firm’s highest security priorities, and leverage third parties and on-demand specialists to address the rest.

Aside from managed security services providers who supply general security operations support, there is a natural stigma against using third parties for cybersecurity resource needs. Arguments vary, but it is typical for my clients to highlight concerns about external access to sensitive assets, data protection needs, and malicious threat actors posing as contractors. While those are all legitimate concerns for contract professionals and support personnel, these issues are fairly simple to address through common controls, such as providing managed endpoint equipment and conducting background checks. Partnering with a third party with a demonstrated global capacity to thoroughly vet specialists for identity, background, and experience can provide additional assurance.

Even in the best-resourced enterprises, it makes little sense to hire full-time super-specialized employees for fractional needs. But a legacy mindset that centers cybersecurity defense on internal hires bolstered by an amenable budget makes such an unproductive practice common. However, for the vast majority of organizations that operate with very lean budgets, CISOs can adapt to changing needs in a more agile fashion by utilizing third-party resources to augment lower priority areas.

Having a partner available with the expertise to help map out a resourcing strategy that takes advantage of contemporary resourcing tools can mean the difference between ignoring unacceptable risks and managing comprehensive cyberdefense capabilities.

Optimal Security Through Archetype Alignment

While it may be true that many CISOs advance up the corporate ladder from technical backgrounds, as I did, security professionals can come from a wide range of educational and professional paths. What they generally have in common, however, is a persistent curiosity about how things work, an inherent sense of empathy, and an extraordinary affinity for crisis management.

Information security professionals operate under persistent and unyielding adversity, with threat actors constantly probing and experimenting with different tactics to find just one unprotected point-of-entry. There may be no absolute security, but failure does not need to be a given. Exploitable weaknesses are often less about incompetence than a defensive failure of imagination in an asymmetric battlefield where the attackers vastly outnumber the defenders.

By aligning a security program with an organization’s security personality, security executives can more effectively prioritize their defensive attention, manage business risks, build buy-in across the leadership team, and instill a stronger culture of security. Maybe then, those three envelopes we talked about can remain safely unopened and forgotten.

Have a question for Michael or his Information Security team? Get in touch.

About the author

Michael is the Information Security Practice Lead at Toptal. He holds a bachelor’s degree in brain and cognitive sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a master’s degree in high-tech crime investigations from George Washington University. Before joining Toptal, Michael served as executive director of the Advanced Cyber Security Center, and held other roles in the field, including consultant, principal investigator, advisor to government officials, and chief information security officer.

PREVIOUSLY AT