Enterprise Navigation: Design Methodologies for Stakeholder Collaboration

Designing (or redesigning) an enterprise navigation system can be daunting. This design methodology provides a clear framework for leading a team through brainstorming, decision-making, and preparing for the rest of the UX design process.

Designing (or redesigning) an enterprise navigation system can be daunting. This design methodology provides a clear framework for leading a team through brainstorming, decision-making, and preparing for the rest of the UX design process.

For 20 years, Andi has lead enterprise clients through complex system overhauls by collaborating with exec leadership and end-users alike.

PREVIOUSLY AT

Designing (or redesigning) an enterprise navigation system is not a task taken lightly. Enterprise applications serve a large number of users, accommodate a wide range of personas, and contain a significant volume of content and features. Some enterprise applications even have multiple web-based desktop and mobile products which need to integrate seamlessly for a more enjoyable user experience.

Though this may appear to be a daunting or even impossible task best handled by a large team of “experts,” a solo information architect or UX designer can single-handedly tackle an enterprise application UX design overhaul—as long as she follows an effective methodology for stakeholder collaboration.

“When eating an elephant, take one bite at a time.” - Creighton Williams Abrams Jr.

About Enterprise Navigation Design Systems

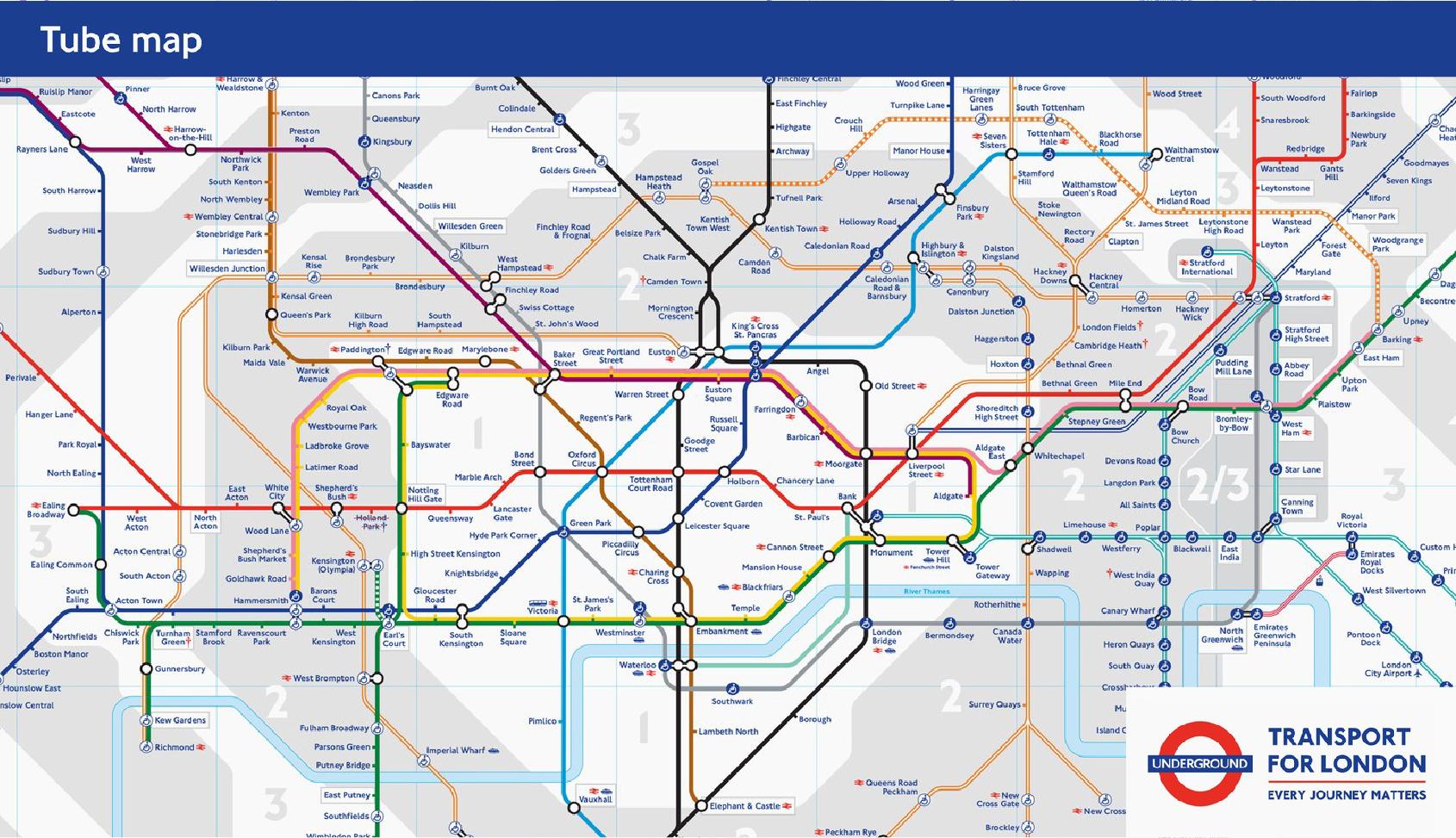

The primary differences between enterprise applications and smaller web-based systems are the sheer volume of content and variety of features. Where smaller systems may effectively rely on a relatively flat navigation system (i.e., fewer clicks to access all of the content), enterprise application architecture often requires multi-level menus and carefully placed wayfinding mechanisms. The more complex the navigation system, the more important it is that the system itself is easy to use, well-organized, and in alignment with the user’s mental model.

The end goal may be clear, but if there were a “perfect” design for an enterprise navigation system, every enterprise would have adopted it. Without a perfected system, there is a lot of room for improvement, creativity, and innovation. It also reveals the fact that every enterprise is different, with varying use cases and requirements for navigation through a complex application.

Navigation is Simply “Wayfinding”

Fundamentally, navigation is “wayfinding.” Seafaring ships may navigate a wide open ocean by using the stars; land-travelers may find their destination with the help of landmarks; and, enterprise application users reach their end goals by relying on various digital indicators.

For example, in the digital universe, navigation depends on the selection and placement of keywords, labels, color, iconography, call to action objects, and other in-screen indicators. When content is poorly organized, features are unintuitively labeled, keywords are haphazardly selected, or icons are obtuse or non-conventional, users may become frustrated or lost… and they may just leave.

Methodology for Collaboration in Navigation Design

Enterprise environments are inherently complex and require a great deal of organization to function effectively. No single person can intuitively know or understand the entire scope of an enterprise application or the unique and varied expectations of its user base. There are many opinions regarding which deliverables are essential to any given design methodology. Regardless of what is created in the end, any methodology should begin with stakeholder collaboration.

1. Stakeholder Kickoff Meeting

Any large-scale project should begin with a stakeholder kickoff meeting. Fundamentally, this is a big meeting with all key players in attendance (remotely or onsite) to jumpstart the project. Typically, a stakeholder kickoff meeting has a single facilitator who introduces the project goals, identifies all the stakeholder roles, and defers to project leads (where appropriate) for additional context, so that collaboration can begin.

The larger the team, the more important it is to hold an official stakeholder kickoff meeting. Much like the opening ceremony of the Olympics, this somewhat ceremonial starting point for a project makes it clear to all stakeholders that “the games have begun.”

As a designer, it is best to obtain the list of stakeholders and their roles as a reference when scheduling navigation design sessions and interviews. Everyone on this list is important and valuable to the work that needs to be done.

2. Blue Sky Brainstorming

With all of the stakeholders identified and engaged, find time to meet in smaller groups or schedule individual interviews to conduct brainstorming and ideation sessions. By opening the door to dream about a “blue sky” future, individuals are less likely to filter their ideas or opinions, and innovation is given a chance to spread its wings.

In many cases, historical roadblocks or unfounded limitations may persist in the minds of stakeholders but no longer exist in reality (due to, for example, new technology, changes in the marketplace, changes in revenue generated by the enterprise application, or other factors). When stakeholders share concerns about these barriers, try to ask “why” before accepting them as they are. There may be hidden opportunity here.

To initiate this brainstorming process, start with a few questions:

- If you were to jump ahead 5 or 10 years into the future with no limitations or roadblocks, what would you like to see in the future design?

- Have you had any ideas—regardless of how easy or complicated—but no opportunity to bring them to life?

- If you were the CEO of this company, what would you do in this situation?

- Do you see any needs in the marketplace which could be served by this application?

It may seem like this approach would open a “can of worms,” but as long as everyone is clear on the “blue sky” scenario, great things can happen. Give it a try!

3. Pain Points and Problem Identification

When users are experiencing pain or frustration with navigating through a large-scale enterprise system to find content or features which should be more readily accessible, those users are more likely to give up and (sometimes) find an alternative. That alternative may be with a competitor.

Be realistic and aggressive about identifying user pain points and problems. Many stakeholders have direct access to user feedback through surveys, training sessions, and other forms of communication. Leverage this knowledge to gain a better understanding of how the current enterprise navigation system is failing.

These questions can get the ball rolling with identifying pain points and problems:

- What do users complain about the most?

- Do you use any services (such as web traffic analytics or click tracking) that track user behavior in the system?

- Are there areas of the enterprise system that are rarely used, and you can’t explain why?

- If you could change anything about this application, what would it be?

Insight into where users are having trouble will play a major role in identifying gaps in the current design. Capture these points for use in this methodology.

4. Affinity Diagramming

As a designer, “sticky notes” can be your best friend. But if too many stakeholders are not located in the same office or you are the only remote resource, paper sticky notes are used in vain. Finding an effective approach for online collaboration is critical. There is a wide variety of online collaboration tools which can be used to capture all of the inputs from the Blue Sky Brainstorming and Pain Points and Problem Identification phases.

Once you have captured a significant amount of input, the next step is to organize that input into affinity groups. Affinity diagramming is a collaborative exercise which allows all stakeholders a chance to find relationships or shared features between individual ideas or content types. This exercise enables a designer to bring all of the “blue sky” ideas and “pain points and problems” together.

For example, it might help to group process and procedure content into a library, or current events and news-worthy updates into a consolidated online newspaper. Encourage stakeholders to be creative about how they formulate affinity groups.

In the stakeholder affinity diagramming sessions, ask questions like these:

- Which features or content feel like they belong together?

- Are users trying to take certain actions which would be easier if they occured in sequence?

- Are there any redundant capabilities that might be easily merged or simplified?

- Is there any opportunity to match up blue sky ideas with existing pain points or problems?

Encourage stakeholders to think of specific scenarios which bring users to a given feature within the system. Using real-life scenarios puts things into perspective and makes it easier for stakeholders to be empathetic to the user experience.

5. Logical Reorganization

After the affinity diagramming exercise is complete, it is important to step back and look at the system holistically. There is often a logical order of operations which a user can follow within any given complex environment. Carefully consider whether there are opportunities to provide a service that is not currently available (innovation), or to encourage a user to expand her utility of the enterprise navigation system (discovery) by providing wayfinding indicators.

To capture this logical organization or order of operations, a designer may create a flowchart or, in more complex scenarios, a user journey map, beginning with the primary workflow, and then branching off into other content or features.

Questions that might encourage your stakeholders include:

- Now that the user is “here,” what else can she do?

- What is the next logical activity for the user in this scenario?

- Are we missing any opportunities to solve the user’s problem from this vantage?

- Are there features or content that exist elsewhere that could be useful in this scenario?

Once you have gotten the conversation going on this topic, collaborate with stakeholders to rearrange the affinity groups accordingly.

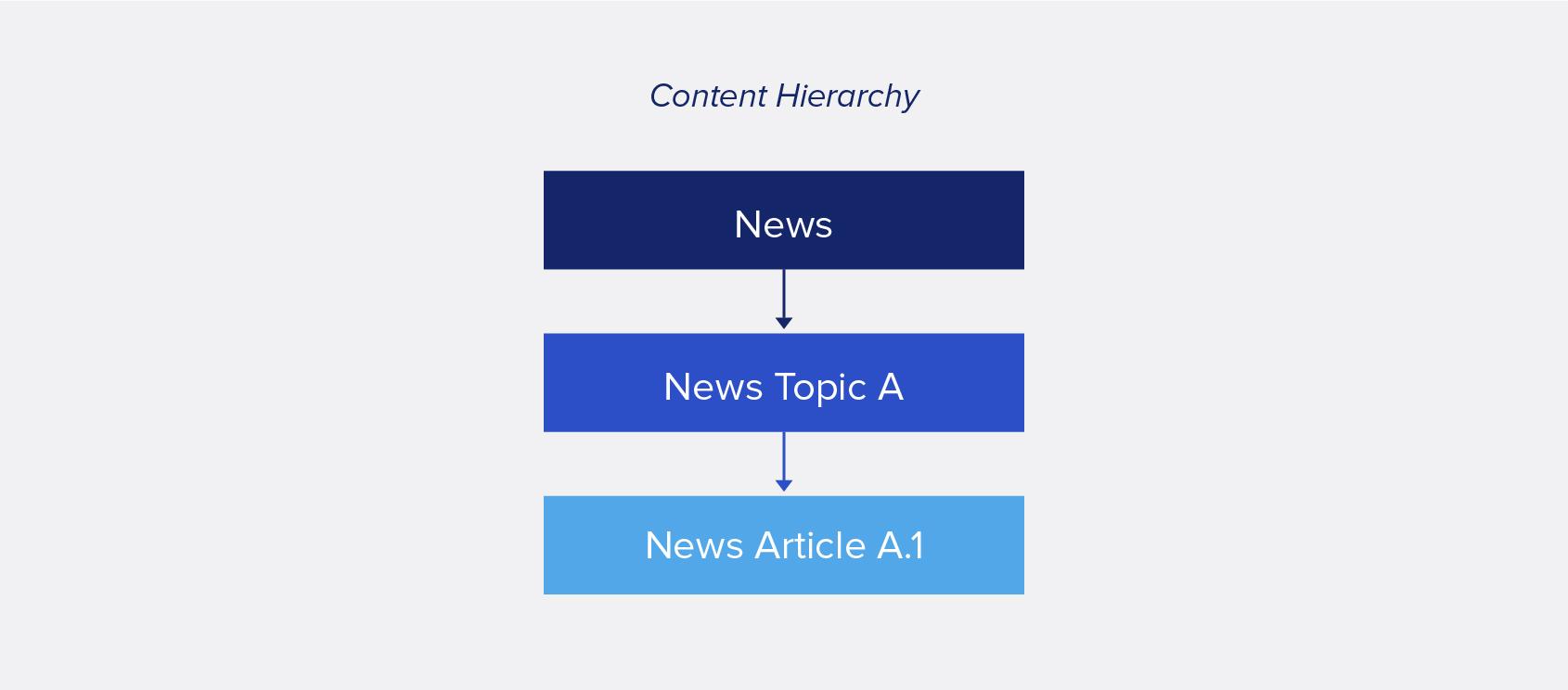

6. Hierarchy

Within a larger affinity group or between individual affinity groups, there will likely be relationships or dependencies. Work with stakeholders to identify those relationships or dependencies, and then organize them into hierarchies. A hierarchy is simply a fancy way of describing how a piece of content or a feature belongs to a group of like content or features. For example, a single news article belongs to a topic, and the topic belongs to a section dedicated to news.

Warning!

At this point in the design process, stakeholders may want to use existing corporate departmental organization as a baseline for the enterprise system hierarchy. Although it is easy to mimic the enterprise departmental organization (which is typically where content and feature ownership lies), this can be a huge mistake!

Users do not care who owns the content. Moreover, since large enterprises like to reorganize frequently, the enterprise navigation design system that aligns with departmental organization will no longer be valid as soon as the first “reorg” occurs.

Leverage the methodology presented thus far, and push back on this dangerous approach. These questions can help facilitate a conversation with stakeholders:

- How are these affinity groups related, and why are they related?

- Are there any dependencies between the affinity groups that we need to acknowledge?

- Will users be able to complete a task without having to navigate to another area of the system?

- Are there conventional hierarchies that are familiar to users from within other industries or service models that can be used as a reference?

At this point in the design process, there are many ways to verify whether the approach is working. Consider different methods of user testing and user research to confirm your hierarchy, or to identify problem areas that require more attention.

7. Nomenclature and Parameters

With a complete model of the future enterprise application architecture—also known as the information architecture—it’s time to select keywords (nomenclature) and set parameters (definitions).

Nomenclature, or labeling, is an important element of navigation design for three primary reasons: (a) nomenclature is directly related to SEO (search engine optimization) in that search engines primarily are searching for content by keywords; (b) using proper terminology as a wayfinding mechanism will help users to find what they seek by serving as a digital “landmark;” and (c) smart labels can lead users to an area of the system that may not be readily accessible from a primary landing page or home page. Findability is driven by wayfinding mechanisms, like labels. If a label is misleading or not intuitive, the user may not bother to click on it at all.

With all of the nomenclature (labels) identified in the information architecture model, collaborate with stakeholders to define parameters (definitions) for each labeled area in the model. This will ensure that content and features belong to a particular area. Additionally, this exercise creates long-term guidelines for building out the enterprise application architecture which will outlast the current design process.

Regarding nomenclature and parameters, here are a few questions to ask stakeholders that will drive the conversation:

- What are users most often searching for when they visit?

- Are any content or features hard to find? Why are they hard to find?

- Are there industry terms or lingo that could be unfamiliar to some users, making it harder for them to find what they are seeking?

- How can we choose labels that are conventional or mainstream?

As aforementioned, there are many different methods that can be used to test nomenclature, such as card sorting, A/B testing, and object-oriented UX (OOUX). When dealing with a highly technical enterprise system with tons of industry lingo, consider building a controlled vocabulary or in-system glossary for user reference.

8. Integration with User Experience Design Process

With a complete picture of the future information architecture, it’s now time to apply the results of this methodology to the overall user experience design process.

Although there may be areas of the newly minted enterprise navigation system that don’t exist when the design project is in flight, those areas can be “disabled” or hidden until the content or features are ready to be released. Then, after the designer has moved on, stakeholders can continue building out the system towards their “blue sky” dreams.

“If you build it, [they] will come.” - Field of Dreams, 1989.

The Bottom Line

Designing an enterprise navigation system is not an easy task. However, leveraging the knowledge of stakeholders will make that effort manageable.

Setting aside the complexity of large-scale design projects, the goal is always to keep the user in mind. With a hands-on approach to user research, and asking smart questions of the people who have direct contact with the user, even a remote, solo, or freelance designer can handle big design problems. Don’t be intimidated—just take things one step at a time.

Andi Omtvedt

Silverthorne, CO, United States

Member since September 18, 2017

About the author

For 20 years, Andi has lead enterprise clients through complex system overhauls by collaborating with exec leadership and end-users alike.

PREVIOUSLY AT