Designing VR Games Worth Playing: 6 Key Considerations

Despite decades of hype, virtual reality gaming has failed to be widely adopted. Better design can reduce player frustration, increase comfort, and make games more immersive.

Despite decades of hype, virtual reality gaming has failed to be widely adopted. Better design can reduce player frustration, increase comfort, and make games more immersive.

Edward is a veteran UX designer with a résumé of award-winning projects for Google, Sony, Electronic Arts, and Sega. He’s worked on iconic gaming franchises like Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, and Sonic. In 2014, he launched a company to contribute strategic gamification and UX services to nongaming companies seeking to leverage AR/VR technology.

Previous Role

Lead UX DesignerPREVIOUSLY AT

Featured Experts

Previously at Oracle

10 years of experience

6 years of experience

In 2014, after working as a video game designer for more than a decade, I noticed a shift in the gaming industry. Oculus had just released the first version of the Rift—a head-mounted display aimed at mainstream gamers—giving rise to the modern VR gaming landscape. I, along with many other game developers in my network, decided to transition from working on traditional games to creating virtual reality ones.

Yet, in 2022, according to the Entertainment Software Association, only 7% of 215.5 million US gamers reported playing on a VR system, compared to 52% who played on a console.

So why hasn’t VR gaming taken off?

Until recently, to get the best VR experience, such as that provided by the HTC Vive, consumers had to invest in a costly high-end gaming PC, not to mention a cumbersome external sensor setup. In some cases, early software also caused disorientation and motion sickness. But at $399, Meta’s Quest 2 VR headset (released in October 2020) provides a comparable experience to the Vive—with superior input and internal positional tracking technology and improved ergonomics—at a more affordable price.

Even with these technological advances, there remain challenges to widespread VR gaming adoption, including players feeling overwhelmed by virtual environments, struggling with nonintuitive gameplay, experiencing physical discomfort, and not being immersed in virtual worlds.

These are challenges that designers are poised to tackle. In this article, I share design insights from fellow Toptal experts and address what needs to be done to make VR gaming experiences more appealing to the masses.

Designing for Relatability and Different Perspectives

As hardware and technical features improve, as they inevitably do, designers must explore a more fundamental question: Why should a game be created in VR?

Radu Anghel, a Toptal UX designer and senior user experience designer at Oracle, says the value of VR lies in games that are relatable to real life while providing experiences that help players see things from new perspectives. For instance, few of us are called to engage terrorists in combat, like in Counter-Strike. Yet, many of us might benefit from a deeper understanding of mental illness, which VR’s immersive environments are uniquely suited to convey, Anghel says. Take Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. This game, created in collaboration with neuroscientists and people with mental health issues, was initially published in 2D—but Anghel says it works better in VR. Hellblade lets a player embody Senua, a warrior battling psychosis that visually distorts Viking foes into monsters and manifests the nightmarish goddess Hela. These enemies and stereo-panned voices emulating auditory hallucinations are even more affecting—and destabilizing—in a swirling 3D space than they were in 2D. “The game helps players imagine and experience a certain reality,” Anghel says.

Many players who have mental illness have lauded the BAFTA Award-winning game’s realistic, empathetic design.

In a starkly different application, Toptal designer and technical artist Austin Booker points to Anne Frank House VR, an educational game that re-creates the Secret Annex in 1942 Amsterdam, where the 13-year-old Frank hid from the Nazis with her family and others. Booker says that the game is a prime example of how haptic models of user interaction can take gamers deeper into the subjective realities of others. Players see text written onto the walls and use their controllers like hands to mimic the sensation of turning door handles to expose unknown dangers.

“You’re going through the tunnels she went through; you’re looking inside the bedrooms and passageways she had to go through, while listening to the narrator explain passages from her diary,” Booker says.

The game is an achievement on many levels. But, as Booker notes, playing should be done thoughtfully, since walking in Frank’s shoes could be frightening, even traumatic, for some players. With that in mind, if a digital experience designer seeks to elicit empathy from their audience, VR affords considerable immersive advantages over traditional platforms.

Making Players Feel Safer and More in Control

VR’s capacity to foster creativity and give players agency and psychological insight is also its Achilles’ heel. As VR pioneer Jaron Lanier told The Washington Post, he believes players can be easily overwhelmed when dropped into an unfamiliar virtual world—especially since most players are used to the sense of control and familiar interfaces that comes with playing traditional video games contained within 2D monitors.

To orient players in VR, game designers might look to architects and industrial designers who’ve been wrestling with 3D space for decades. Consider the ergonomic experience of driving a car. Dashboard displays are arranged according to their priority: The speedometer is front and center; less frequently used controls, like hazard lights, are harder to find. Managing users’ focus in a 3D world is about helping them prioritize the demands of quickly shifting stimuli.

In VR, “you’re focused on a 15-degree angle, left and right, up and down,” Anghel says. “Anything outside that area gets less attention.”

Then again, a player’s peripheral vision may be prime real estate for less-urgent game information that is traditionally located in heads-up displays, like health and stamina indicators, object inventories, skill sets, and boundary maps. This information can also be embedded in the materials of the world itself: signs, backpacks, mailboxes, or phones that function much like they do in the material world.

Better still, the design elements of 2D games—menus, toggles, switches, checkboxes, and drop-downs—can be disguised in gameplay. In Job Simulator, a game in which robots have overtaken all human jobs, players can go through a training simulation to learn about obsolete professions, such as office worker and auto mechanic. In the opening selection menu, players must manually insert a data cartridge into an archaic computer console to choose a career training simulation. This action advances gameplay and visually supports the game’s conceit. Players then learn and perform the duties of their chosen profession, like flipping burgers or filing papers.

Embracing Constraint to Create Intuitive Interactions

Myriad usability problems plagued early VR gaming as a result of inferior standards of input and sensor technology. For example, earlier iterations of VR headsets were limited to a single external camera or sensor, which made it hard to maintain the user’s physical orientation within the virtual environment. Users had to be taught how to recalibrate themselves to overcome this limitation, introducing friction and increasing cognitive load.

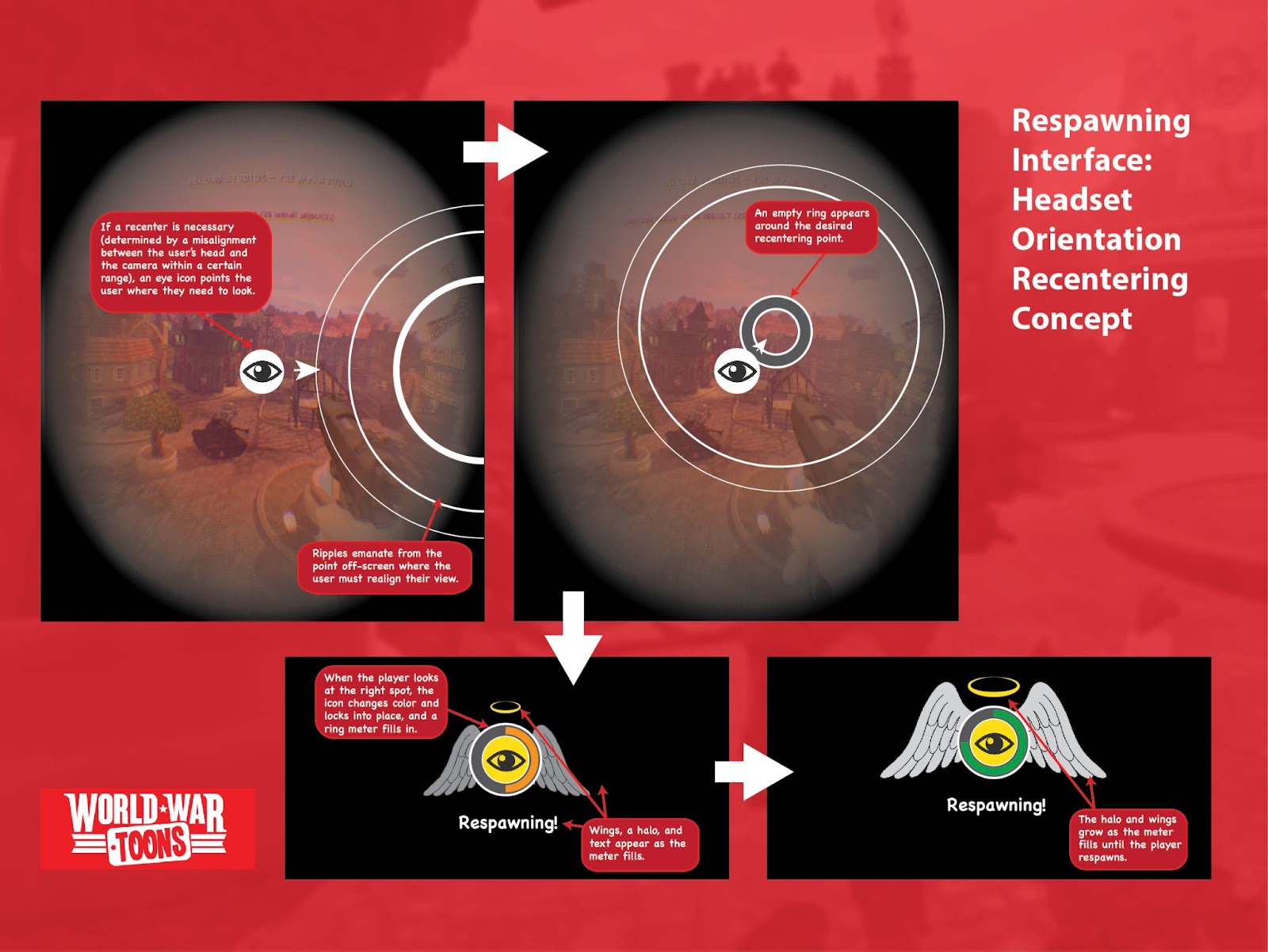

Clever design and programming can make this recalibration easier and less noticeable. In World War Toons—a playful, cartoonish take on multiplayer shooters released for the original Oculus Rift and Sony PlayStation VR—for example, the developers disguised and piggybacked recalibration into the cycle of dying and respawning. The diagram below illustrates how offscreen ripples attracted the user’s attention toward the camera during respawning, using playful angel wings and halos that grow once the recalibration completes.

Understanding the ever-changing possibilities and limitations of VR hardware platforms and embracing constraints can create opportunities for inventive design solutions—making interactions simpler and more intuitive for players.

Minimizing Motion Sickness and Disorientation

In addition to usability issues, many early VR games focused on the wrong use cases: transplanting first-person shooters to VR worlds or using spherical cameras to create roller coasters or flight simulators. Side-to-side movement, which creates a parallax effect, is one of the most stomach-turning VR experiences, largely because new stimuli suddenly enter gamers’ field of view, making it hard to focus and feel settled. Acceleration can be equally nauseating because it exacerbates the disconnect between players’ visually induced feeling of movement and their actual stillness.

Movement in first-person shooters tends not to work as it does in real life: We don’t typically strafe left and right or walk backward—we rotate and walk forward. Then there are times when the player isn’t moving but their character is. When the body’s kinesthetic sense indicates people are stationary, but the brain’s visual processor tells them they’re moving, uncomfortable cognitive dissonance occurs.

Several helpful design solutions can be implemented to avoid disrupting the immersive experience. One is creating a consistent visual frame of reference, such as a horizon or cockpit, which reduces motion sickness by giving the brain something fixed to focus on. Another is creating a tunnel vision effect while the player is moving forward, reducing the number of changing stimuli in their vision. And in-game teleportation allows players to quickly travel great distances.

According to Tade Ajiboye, a Toptal Unity developer and VR software engineer, two notable examples of this last solution exist in Valve’s Half-Life: Alyx, a VR combat game set in a dystopian future in which players fight draconian robots. Blink teleportation (where the screen momentarily goes black during locomotion) and shift teleportation (where graphics modulate according to players’ movement) let people select a target location and travel there almost instantaneously. Ephemeral yellow feet show where they’ll land to keep them oriented.

Reducing Eye, Neck, and Shoulder Discomfort

Another common VR gaming problem is eye strain. New headsets, such as the Meta Quest Pro and PlayStation VR2, use eye tracking to detect specifically where the user’s gaze is focused. Headsets with this capability can respond to changes in the user’s gaze in real time. They can also employ a technique called foveated rendering, which blurs images in the user’s periphery rather than displaying the whole field of view at a consistent level of detail (more like how the human eye works). The result is more photorealistic rendering, smoother, more performant frame rates (low frames per second is a key contributor to motion sickness and discomfort), and more efficient power consumption. Eye tracking also enables users to hit a target with a virtual stone just by looking at the target. Designers can leverage this input data to render the objects of users’ attention in greater detail—limiting eye strain as players focus on key elements.

VR gamers have also complained of neck and shoulder discomfort. With earlier hardware like the Oculus Rift, Booker says, the headset’s weight and short leash resulted in neck pain. Lightweight, wireless models have resolved that, but there’s still an issue with the motions and positions required in many VR games: To view various stimuli, players often have to tilt their heads up or down for lengthy periods and rotate them too far or too rapidly, resulting in stiff, sore necks. Sometimes they have to keep their arms elevated too long, putting strain on their shoulders.

To rectify this, designers should put the text that players need to read or objects they need to interact with closer to their bodies and at eye level. Aleatha Singleton’s diagram of reading distances in XR shows that viewers have a comfortable head-turning arc of 154 degrees and a reading radius of two to three meters. An innovative approach, leveraged in VR games like StarBlood Arena for Sony PlayStation VR, augments the degree of rotation of the user’s head so the virtual camera changes its orientation faster. With this clever design, users can better perceive more of the virtual environment, reducing neck and shoulder strain while making VR gaming feel more natural for players.

Creating Fully Immersive VR Gaming Experiences

Even with recent hardware improvements, VR gaming still faces significant hurdles, chiefly creating new heuristics for user interfaces. To be immersive, “games need to make users forget they’re in virtual spaces,” Ajiboye says.

Right now, that’s rarely the case. Immersive designers and developers must create more all-enveloping environments that take players to alternate realities, let them use the physicality of their bodies to navigate, and provide feedback cues to anchor them in space.

Half-Life: Alyx, as explored earlier, is a game that hits many of these targets, according to Ajiboye. Players can move step by step with directional controls for a lifelike experience. Even when they’re using the less-realistic teleportation features, acoustic cues like reverberating footfalls and the jangle of ammunition rounds make these movements sound real.

Adding to the game’s verisimilitude is that players’ physical bodies, positions, and orientations remain intact when translated to VR, and players can turn, crouch, contort themselves, or interact with their environments in a manner that’s true to their physical shape.

Other titles take a different approach to realistic locomotion, restricting players to fixed locations. In Beat Saber, a rhythm game that builds off hits like Dance Dance Revolution and Guitar Hero, players use their arms as input devices, swinging controllers to slash at falling neon cubes while their feet remain planted.

Players lack the agency to traverse multiple vectors, but the simple, intuitive gameplay, set to popular music, limits the need for wayfinding arrows and dialogs that can break the illusion of being in an alternate world. Propelled toward cubes at a constant speed, players know where they are and what they’re trying to accomplish.

And immersion is not all about movement. Narratives, especially in character-driven games, elicit players’ emotional responses. VR affords a new way of bringing games’ stories to life by putting players at the center of a virtual world and enhancing their feelings.

“The best VR games I’ve seen engage the user through storytelling,” Booker says. “Once they believe the story, they start to bleed into the actual character in the game.”

What’s Next for VR Gaming Designers

There’s a bit of a running joke in this space that mainstream success for VR will always be five to 10 years away. So far, Quest has been most successful at reaching that mainstream audience, offering better UX at an affordable price. But for many users, it’s still clunky. To appeal to an audience outside of tech enthusiasts, the hardware will need to become more compact, comfortable, affordable, fashionable—and, of course, easy and enjoyable to use.

Designers should understand the capabilities that new VR hardware and platforms afford so they can provide users with the highest quality immersive experience. Regardless of the medium we’re working with, the job of the UX researcher and UX designer hasn’t changed. To design effective, immersive VR experiences, we still need to talk to users, understand their problems, test, and iterate. It’s only the context that has changed: We’re moving away from designing primarily for digital inputs like buttons, and instead we have the exciting opportunity to craft highly intuitive, artificial realities and interact with them using the voice, eyes, and body as input mechanisms. By continuing to apply UX best practices to VR gaming, designers can push the envelope toward innovation and greater adoption.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

Understanding the basics

What is VR in UX design?

VR, or virtual reality, is a technology that allows users to enter simulated alternate worlds and feel and act as though they’re in those environments. In UX design, VR provides a 3D medium for designers to make experiences such as video games more lifelike and immersive.

What makes a good design of a game?

In VR gaming, the things that constitute good design include simple and intuitive interactions, UX elements and positional tracking sensors that reduce motion sickness, fully immersive environments, a UX that promotes empathy, and features that help orient players and manage their attention.

What does a VR game designer do?

A VR game designer imagines and creates virtual reality video game worlds and stories for players. This role involves animation, modeling, and other techniques. VR game designers may work on the user experience, user interface, or both.

Los Angeles, CA, United States

Member since June 29, 2020

About the author

Edward is a veteran UX designer with a résumé of award-winning projects for Google, Sony, Electronic Arts, and Sega. He’s worked on iconic gaming franchises like Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, and Sonic. In 2014, he launched a company to contribute strategic gamification and UX services to nongaming companies seeking to leverage AR/VR technology.

Previous Role

Lead UX DesignerPREVIOUSLY AT